Expiring Detention Authority and the Viability of Prosecutions in the Military Commissions Under Hamdan II Reema Shah and Sam Kleiner*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

\\Crewserver05\Data\Research & Investigations\Most Ethical Public

Stephen Abraham Exhibits EXHIBIT 1 Unlikely Adversary Arises to Criticize Detainee Hearings - New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/23/us/23gitmo.html?pagewanted=print July 23, 2007 Unlikely Adversary Arises to Criticize Detainee Hearings By WILLIAM GLABERSON NEWPORT BEACH, Calif. — Stephen E. Abraham’s assignment to the Pentagon unit that runs the hearings at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, seemed a perfect fit. A lawyer in civilian life, he had been decorated for counterespionage and counterterrorism work during 22 years as a reserve Army intelligence officer in which he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. His posting, just as the Guantánamo hearings were accelerating in 2004, gave him a close-up view of the government’s detention policies. It also turned him into one of the Bush administration’s most unlikely adversaries. In June, Colonel Abraham became the first military insider to criticize publicly the Guantánamo hearings, which determine whether detainees should be held indefinitely as enemy combatants. Just days after detainees’ lawyers submitted an affidavit containing his criticisms, the United States Supreme Court reversed itself and agreed to hear an appeal arguing that the hearings are unjust and that detainees have a right to contest their detentions in federal court. Some lawyers say Colonel Abraham’s account — of a hearing procedure that he described as deeply flawed and largely a tool for commanders to rubber-stamp decisions they had already made — may have played an important role in the justices’ highly unusual reversal. That decision once again brought the administration face to face with the vexing legal, political and diplomatic questions about the fate of Guantánamo and the roughly 360 men still held there. -

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-366 November 2003 Articles Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials: A Rebuttal to Military Commissions: Trying American Justice Colonel Frederic L. Borch, III Editorial Comment: A Response to Why Military Commissions Are the Proper Forum and Why Terrorists Will Have “Full and Fair” Trials Kevin J. Barry, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Coast Guard Afghanistan, Quirin, and Uchiyama: Does the Sauce Suit the Gander Evan J. Wallach Note from the Field Legal Cultures Clash in Iraq Lieutenant Colonel Craig T. Trebilcock The Art of Trial Advocacy Preparing the Mind, Body, and Voice Lieutenant Colonel David H. Robertson, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center & School, U.S. Army CLE News Current Materials of Interest Editor’s Note An article in our April/May 2003 Criminal Law Symposium issue, Moving Toward the Apex: New Developments in Military Jurisdiction, discussed the recent ACCA and CAAF opinions in United States v. Sergeant Keith Brevard. These opinions deferred to findings the trial court made by a preponderance of the evidence to resolve a motion to dismiss, specifically that the accused obtained and presented forged documents to procure a fraudulent discharge. Since the publication of these opinions, the court-matial reached the ultimate issue of the guilt of the accused on remand. The court-martial acquitted the accused of fraudulent separation and dismissed the other charges for lack of jurisdiction. -

Print: Bush's Plan to Erode Our Liberties

Print: Bush's Plan to Erode Our Liberties http://www.thenation.com/doc/20070625/huq/print Bush's Plan to Erode Our Liberties by AZIZ HUQ June 8, 2007 Early this week, judge advocates halted two prosecutions in the Guantánamo military commissions established under the 2006 Military Commissions Act (MCA). This is not the first setback the Administration's second-tier court system has hit; the Supreme Court invalidated an earlier iteration of the commissions in 2006. And it won't be the last. But while this week's setback likely will be speedily surmounted, it casts an unexpected light on the MCA's real purposes, and what's at stake when the Bush Administration plays politics with national security. Understanding the significance of this week's ruling means delving into a bit of procedural arcana. The devil in the MCA is, almost literally, in the details--and unless we attend closely to the rococo details of the statute, we'll miss the ways in which the Administration intends to slowly erode our liberties. At the beginning of this week, the military commissions' two judges--Army Col. Peter Brownback and Navy Capt. Keith Allred--dismissed charges filed against Omar Khadr and Salim Hamdan. The rulings focused on a question of categorization--basically, the judges found that Khadr and Hamdan had been wrongly classified. But how did this happen? The MCA, which created the military commissions, states that only an alien who is an "unlawful enemy combatant" can be tried in a military commission. It also defines "unlawful enemy combatants" in tremendously sweeping terms to include anyone who has "materially supported hostilities." Many civil libertarians, including myself, expressed grave concerns about the scope of this provision. -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

The Personal Jurisdiction of Military Commissions1 (August 9, 2008)

Taking Liberties: The Personal Jurisdiction of Military Commissions1 (August 9, 2008) Madeline Morris2 with Yaniv Adar, Margarita Clarens, Joshua Haber, Allison Hester-Haddad, David Maxted, James McDonald, George (‘Wes’) Quinton, Dennis Schmelzer, and Jeffrey Ward I. Introduction On September 11, 2001, Al Qaeda operatives attacked civilian and military targets on US territory, causing thousands of deaths and billions of dollars of economic loss. The next day, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1368 characterizing the attack by Al Qaeda as a “threat to international peace and security” and recognizing the right of states to use armed force in self defense.3 NATO, for the first time in its history, invoked the obligation of collective self defense under Article 5 of the NATO Treaty.4 On September 14, the US Congress passed the Authorization for the Use of Military Force, authorizing the President to use “all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks. .” 5 Terrorism, conceived until then as crime, was reconceived—as war. On November 13, 2001, invoking the law of war, President Bush announced that enemy combatants in the US “war on terror” would be subject to trial by military commission—a form of military tribunal last convened in the aftermath of World War II. Issuing a Presidential Military Order (PMO), he stated: 1 © Madeline Morris 2007. 2 Professor of Law, Duke Law School. 3 S.C. Res. 1368, U.N. SCOR, 56th Sess., 4370th mtg., U.N. Doc. S/RES/1368 (Sept. 12 2001). -

Responding to War on Terror Detainees' Attempts to Dismiss

0070.BLOOM 10/25/2007 10:58 AM Matthew Bloom “I Did Not Come Here To Defend Myself”: Responding to War on Terror Detainees’ Attempts To Dismiss Counsel and Boycott the Trial abstract. A significant portion of the war on terror detainees who have been charged at Guantanamo have announced their intentions to dismiss their attorneys, to waive their right to be present at their trials, or to take both actions simultaneously so that their interests will not be represented. This Note demonstrates that strong justifications, rooted in international and domestic legal rules and precedent, support honoring the detainees’ requests. Yet the military tribunal proceedings are designed to follow the adversarial model to achieve just outcomes; granting the detainees’ procedural requests can, in certain situations, undermine the ability of the military commissions to reach just outcomes in favor of the personal whims of the detainees. When a detainee’s procedural request threatens to undermine the adversarial model, I propose that military adjudicators appoint an amicus curiae counsel to provide sufficient process on behalf of the tribunal. author. Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2008; Yale University, B.A. 2005. The author is especially indebted to Professor Michael Wishnie for his support and advice throughout this project. He also wishes to thank Maj. Thomas Fleener and Lt. Cmdr. William C. Kuebler of the U.S. Department of Defense Office of Military Commissions for their firsthand insights; Professor Muneer Ahmad, Peter Elikann, Justice Joette Katz, Justice Richard Palmer, Priti Patel, and Katherine Wiltenburg Todrys for their comments on earlier drafts; and Benjamin Siracusa for his expert editing. -

High Command Case: a Study in Staff and Command Responsibility

JOHN JAY DOUGLASS* Colonel, JAGC High Command Case: A Study in Staff and Command Responsibility Less than twenty-five years after the conclusion of the major World War I1war crimes trials, international jurists, historians and the general public are not clear as to, nor are they apparently concerned with, the authority, procedure or even the significant legal decisions of the war crimes trials held both in Europe and the Far East following World War 11.1 Even a mere twenty-five years of experience indicates there will be other trials of those accused of criminal acts in war. Such trials, as well as international lawmakers, should well review the German High Command Trial before the United States Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in October 1948. The lessons of this trial may well be the most important of those from any of the trials held following World War 11. The thrust of this trial and its results relate to the authority of command- ers of military forces for actions of their troops and their personal respon- sibility, as well as the responsibility of staff officers in senior staff positions, for'actions taken by them or carried on under their direction. As a result of recent developments within the United States, arising from the war in Vietnam, it is worthwhile to review the German High Command Trial and to analyze its relationship to the present state of the law. The legal question of criminal responsibility of military commanders and staff officers who do *Commandant (Dean), The Judge Advocate General's School, U.S. -

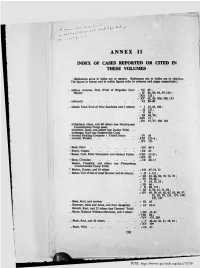

Annex Ii Index of Cases Reported Or Cited in These Volumes

J» ■ i, J L-, UJ> O'- ' / C , " i ANNEX II INDEX OF CASES REPORTED OR CITED IN THESE VOLUMES (References given in italics arc to reports. References not in italics are to citations. The figures in roman and in arabic figures refer to volumes and pages respectively.) Abbaye Ardcnnc Trial (Trial of Brigadier Kurt~ 111 6 9 ; Meyer). ✓ IV 85, 89, 997-110 5 , ; *X1I 123: ✓ X V 62, ¿4, 106,109, 133 - Ahlbrecht ......................................................... X I 89-90 « Almelo Trial (Trial or Otto Sandrock and 3 others)✓ / 35-45,1 0 6 ; ✓ 11 127; w V 1 0 ; . XI 46,50; . X IV 15 ; * X V 47, 97, 108, 184 Allfuldisch, Hans, and 60 others (sec Mauthausen Concentration Camp case). Altstötter, Josef, and others (sec Justkc Trial) .. Ambcrgcr, Karl (sec Dreierwalde Case) - Armour Packing Company v. United States .. s W 54 - Awochi, Washio ..............................................^Xlll 122-4 ; X V 121 » Back, P e t e r ........................................................ ✓/// 60-1 x Bauer, August ..............................................«'IX 65 v Bauer, Carl, Ernst Schramcck and Herbert Falten*Vlll 15-21; v X V 82 v'Baus, Christian ..............................................s l X 68-71 Becker, Friedrich, and others (sec Flossenberg Concentration Camp Trial) t'Becker, Gustav, and 19 others ........................ JVU 67-73,15 ✓ Belsen Trial (Trial of Josef Kramer and 44 others)..11 1-152;✓ ✓ III 6 3 ,6 6 ,6 9 .7 0 ,7 2 ,7 4 ; ✓ IV 79,86 ; ✓ V 14, 15, 23 ; ✓ IX 66 ; ✓ X 68, 173 ; ✓ XI 9,10,11,71,83; ✓ X V 45, 59, 61, 65, 67, 83, 86, 87, 92, 93, 97, 121. -

Some International Law Problems Related to Prosecutions Before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia

SOME INTERNATIONAL LAW PROBLEMS RELATED TO PROSECUTIONS BEFORE THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA W.J. FENRICK* I. INTRODUCTION The presentation of prosecution cases before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (the Tribunal) will require argument on a wide range of international law issues. It will not be possible, and it would not be desirable, simply to dust off the Nuremberg and Tokyo Judgments, the United Nations War Crimes Commission series of Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals, and the U.S. government's Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No.10 and presume that one has a readily available source of answers for all legal problems. An invaluable foundation for legal argument before the Tribunal is provided by Pictet's Commentaries on the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the International Committee of the Red Cross' (ICRC) Commentaries on the Additional Protocols of 1977 to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the few cases decided since 1950, old case law, and various learned articles and treatises. They must be reviewed and analyzed. At the same time, however, just as the prosecutors in the post-1945 war crimes trials argued successfully that customary law had evolved after 1907 and 1929, so it is reasonable to presume that customary law has evolved since the Geneva Convention of 1949 and the Additional Protocols of 1977. It is essential to pay due heed to the principles of nullum crimen sine lege and nulla poena sine lege.1 One must, however, distinguish * Senior Legal Advisor, Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. -

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

Contents Preface xxiii Abbreviations and Acronyms xxvii Acknowledgments xxxiii Foreword xxxvii part I Why 1 chapter 1 Foundations 3 A. Purposes 5 1. Protection of Civilians and Others Hors de Combat 7 Constitutional Review of Additional Protocol II 8 2. Minimize Unnecessary Suff ering 9 3. Mission Fulfi llment 10 B. Key Sources of LOAC 11 1. Treaties 11 2. Customary International Law 13 David J. Bederman, International Law Frameworks 13 C. Jus ad Bellum vs. Jus in Bello 16 1. Jus ad Bellum 16 2. Jus ad Bellum in an Age of Counterterrorism 21 3. Separation of Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello 23 Prosecutor v. Fofana and Kondewa 25 Questions for Discussion 27 xi xii Contents D. Intersection with and Distinction from Human Rights Law 30 Th eodor Meron, Th e Humanization of Humanitarian Law 30 Legality of the Th reat or Use of Nuclear Weapons 32 Fourth Periodic Report of the United States of America to the United Nations Committee on Human Rights Concerning the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 34 Questions for Discussion 37 chapter 2 Basic Principles 39 Jean Pictet, Development and Principles of International Humanitarian Law 39 A. Military Necessity 40 Th e United States of America v. Wilhelm List et al. (Th e Hostages Trial) 42 Questions for Discussion 44 B. Humanity 45 Questions for Discussion 47 C. Distinction 48 Legality of the Th reat or Use of Nuclear Weapons 50 Constitutional Review of Additional Protocol II 52 Questions for Discussion 53 D. Proportionality 56 Questions for Discussion 59 chapter 3 Historical Development of LOAC 61 A. -

De-Cloaking Torture: Boumediene and the Military Commissions Act

CLARKE FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 12/7/2009 9:27 AM De-cloaking Torture: Boumediene and the Military Commissions Act ALAN W. CLARKE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION: TORTURE AS A CLOAKED STATE PRACTICE ................................. 60 A. The Fact of Torture: What We Know and What We Can Infer.............................................................................................. 66 B. Structure of the Argument.......................................................................... 74 II. THE ISSUE’S IMMEDIATE IMPORTANCE .................................................................. 75 III. THE PRESIDENT’S WAR POWERS: ASSUMPTIONS ON THE ROAD TO TORTURE ........................................................................................................ 78 IV. TORTURE’S ROOTS: THE MILITARY ORDER OF NOVEMBER 13, 2001 .............................................................................................................. 84 V. LEGAL PERMISSION TO (CLOAK)T ORTURE........................................................... 88 VI. A MAJORITY IN THE SUPREME COURT STRIKES BACK .......................................... 94 A. Rumsfeld v. Padilla .................................................................................... 94 B. Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.................................................................................... 98 C. Rasul v. Rumsfeld ...................................................................................... 99 VII. THE EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE RESPONSE TO PADILLA, HAMDI AND RASUL ............................................................................................ -

The Case of Military Occupation', the Journal of Modern History, Vol

University of Birmingham International law and the transformation of war, 1899-1949 Gumz, Jonathan DOI: 10.1086/698960 License: Other (please specify with Rights Statement) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Gumz, J 2018, 'International law and the transformation of war, 1899-1949: the case of military occupation', The Journal of Modern History, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 621-660. https://doi.org/10.1086/698960 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: © 2018 by The University of Chicago General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive.