Recognition of Vowel Sounds As a Function of Phoneme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neural Substrates of Hanja (Logogram) and Hangul (Phonogram) Character Readings by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Neuroscience http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1416 • J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 1416-1424 Neural Substrates of Hanja (Logogram) and Hangul (Phonogram) Character Readings by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Zang-Hee Cho,1 Nambeom Kim,1 The two basic scripts of the Korean writing system, Hanja (the logography of the traditional Sungbong Bae,2 Je-Geun Chi,1 Korean character) and Hangul (the more newer Korean alphabet), have been used together Chan-Woong Park,1 Seiji Ogawa,1,3 since the 14th century. While Hanja character has its own morphemic base, Hangul being and Young-Bo Kim1 purely phonemic without morphemic base. These two, therefore, have substantially different outcomes as a language as well as different neural responses. Based on these 1Neuroscience Research Institute, Gachon University, Incheon, Korea; 2Department of linguistic differences between Hanja and Hangul, we have launched two studies; first was Psychology, Yeungnam University, Kyongsan, Korea; to find differences in cortical activation when it is stimulated by Hanja and Hangul reading 3Kansei Fukushi Research Institute, Tohoku Fukushi to support the much discussed dual-route hypothesis of logographic and phonological University, Sendai, Japan routes in the brain by fMRI (Experiment 1). The second objective was to evaluate how Received: 14 February 2014 Hanja and Hangul affect comprehension, therefore, recognition memory, specifically the Accepted: 5 July 2014 effects of semantic transparency and morphemic clarity on memory consolidation and then related cortical activations, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) Address for Correspondence: (Experiment 2). The first fMRI experiment indicated relatively large areas of the brain are Young-Bo Kim, MD Department of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery, Gachon activated by Hanja reading compared to Hangul reading. -

Contents Foreword to the 2020 Edition Vii

Contents Foreword to the 2020 Edition vii Preface to the 2020 Edition viii LEM Phonics 2020: Change Summary ix SECTION ONE Introduction and Overview Phonics and English 2 Philosophy of Learning 5 LEM Phonics Overview 7 Phonological Awareness for Pre-Schoolers 9 The Stages of Literacy 12 Scope and Sequence of LEM Phonics 13 SECTION TWO The 77 Phonograms and 42 Sounds The 77 Phonograms 16 Single Phonograms 17 Multiple Phonograms 18 Successive Seventeen Phonograms 19 The 42 Sounds 20 Sounds and their Phonograms 22 SECTION THREE Handwriting 24 SECTION FOUR The Word List What is the WordSAMPLE List? 28 Word List Resources 30 Word List Student Activities 31 LEM Phonics Manual v SECTION FIVE The Rules Rules in LEM Phonics 34 The Rules: Guidelines and Reference 35 Guidelines for Teaching the Rules 36 Syllable Guidelines 40 Explanation Marks 43 Explanation Marks for Silent e 44 Rules Reference: Single Phonograms 45 Rules Reference: Multiple Phonograms 50 Rules Reference: Successive 17 Phonograms 55 Rules Reference: Teacher Book A 58 Rules Reference: Suffixes 62 SECTION SIX Supplementary Materials Games and Activities 68 Phonological Awareness Test 70 SAMPLE vi LEM Phonics Manual Phonics and English The History of English English is the most influential language in the world. It is also one of the most comprehensive with theOxford English Dictionary listing some 170,000 words in current common usage. Including scientific and technical terms the number swells to over one million words. To develop a comprehensive civilization requires a comprehensive language, which explains in part the worldwide influence English has enjoyed. English as we know it is a modern language which was first codified in 1755 in Samuel Johnson’sDictionary of the English Language. -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

A Probabilistic Model of Ancient Egyptian Writing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository A probabilistic model of Ancient Egyptian writing Mark-Jan Nederhof and Fahrurrozi Rahman School of Computer Science University of St Andrews North Haugh, St Andrews, KY16 9SX, UK Abstract Most are written as Latin characters, some with di- acritical marks, plus aleph Z and ayin c. An equal This article investigates a probabilistic sign is commonly used to precede suffix pronouns; model to describe how signs form words thus sdm means “to hear” and sdm=f “he hears”. in Ancient Egyptian writing. This applies ¯ ¯ A dot can be used to separate other morphemes; to both hieroglyphic and hieratic texts. for example, in sdm.tw=f, “he is heard”, the mor- The model uses an intermediate layer of ¯ pheme .tw indicates passive. sign functions. Experiments are concerned with finding the most likely sequence of The Ancient Egyptian writing system itself is a sign functions that relates a given se- mixture of phonetic and semantic elements. The quence of signs and a given sequence of most important are phonograms, logograms, and phonemes. determinatives. A phonogram is a sign that repre- sents a sequence of one, two or three letters, with- 1 Introduction out any semantic association. A logogram repre- Ancient Egyptian writing, used in Pharaonic sents one particular word, or more generally the Egypt, existed in the form of hieroglyphs, often lemma of a word or a group of etymologically re- carved in stone or painted on walls, and some- lated words. -

A Phonogram Based Word List for Reading and Spelling

A PHONOGRAM BASED WORD LIST FOR READING AND SPELLING Based on the Harris-Jacobson Basic Elementary Reading Vocabularies by ARDELLE LAURENE SCHOOLEY B. Ed., The University of British Columbia, 1968 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Language Education We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA JULY, 1982 ©Ardelle Laurene Schooley, 1982 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ^y^n^yy^T^P ^^SJtrtJsJtTtJ The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date oJ^^j^rrJs^cSn /<?8Z DE-6 (.3/81) ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to reanalyze the graded word lists of the Harris-Jacobson Basic Elementary Reading Vocabularies according to phono• gram components to provide a phonogram-based word list in graded format. The methodology of the study required a three step process. First, all of the words of the Harris-Jacobson Basic Elementary Reading Vocabularies list were typed into a computer in grade level format. -

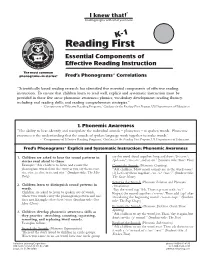

Reading First Program, US Department of Education Fred’S Phonograms® Explicit and Systematic Instruction: Reading Fluency K-1 1

® 4. Reading Fluency, Oral Reading Skills I knew that! “Fluency is the ability to read text accurately and quickly. It provides a bridge between word recognition and comprehen- Reading begins with what you know. sion. Fluent readers recognize words and comprehend at the same time.” - “Components of Effective Reading Programs,”Guidance for the Reading First Program, US Department of Education Fred’s Phonograms® Explicit and Systematic Instruction: Reading Fluency K-1 1. Phonogram words are featured in story contexts, 3. Phonogram words appear in consistent sound- with repetitive text and supportive illustrations. and-letter patterns throughout the stories. Reading First Text example from student title, The Black Shack, follows. Consistent word patterns promote the development of decoding skills and reinforce accuracy. These acquired The Black Shack skills go beyond the pattern, expanding the reach of Essential Components of The tack came off. decoding skills. The rack came off. Effective Reading Instruction The pack came off. 4. Broad reading levels promote the development of Crack! reading fluency. The most common The bear fell back ® Twelve progressive reading levels are included in the phonograms—in stories! Fred’s Phonograms Correlations and lost his snack. series of student books. Quack! Quack! Quack! 5. Reading activities include read-aloud, small group, “Scientifically based reading research has identified five essential components of effective reading 2. Rhymes reinforce rimes! individual, pairs, and silent reading. Phonograms, also known as rimes, in rhyming patterns instruction. To ensure that children learn to read well, explicit and systematic instruction must be Classroom activities are tailored for each student title. invite children into the story. -

Fasold R., Connor-Linton J

0521847680pre_pi-xvi.qxd 1/11/06 3:32 PM Page i sushil Quark11:Desktop Folder: An Introduction to Language and Linguistics This accessible new textbook is the only introduction to linguistics in which each chapter is written by an expert who teaches courses on that topic, ensuring balanced and uniformly excellent coverage of the full range of modern linguistics. Assuming no prior knowledge, the text offers a clear introduction to the traditional topics of structural linguistics (theories of sound, form, meaning, and language change), and in addition provides full coverage of contextual linguistics, including separate chapters on discourse, dialect variation, language and culture, and the politics of language. There are also up-to-date separate chapters on language and the brain, computational linguistics, writing, child language acquisition, and second language learning. The breadth of the textbook makes it ideal for introductory courses on language and linguistics offered by departments of English, sociology, anthropology, and communications, as well as by linguistics departments. RALPH FASOLD is Professor Emeritus and past Chair of the Department of Linguistics at Georgetown University. He is the author of four books and editor or coeditor of six others. Among them are the textbooks The Sociolinguistics of Society (1984) and The Sociolinguistics of Language (1990). JEFF CONNOR-LINTON is an Associate Professor in the Department of Linguistics at Georgetown University, where he has been Head of the Applied Linguistics Program and Department -

Ki-Moon Lee, S. Robert Ramsey, a History of the Korean Language

This page intentionally left blank A History of the Korean Language A History of the Korean Language is the first book on the subject ever published in English. It traces the origin, formation, and various historical stages through which the language has passed, from Old Korean through to the present day. Each chapter begins with an account of the historical and cultural background. A comprehensive list of the literature of each period is then provided and the textual record described, along with the script or scripts used to write it. Finally, each stage of the language is analyzed, offering new details supplementing what is known about its phonology, morphology, syntax, and lexicon. The extraordinary alphabetic materials of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are given special attention, and are used to shed light on earlier, pre-alphabetic periods. ki-moon lee is Professor Emeritus at Seoul National University. s. robert ramsey is Professor and Chair in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Maryland, College Park. Frontispiece: Korea’s seminal alphabetic work, the Hunmin cho˘ngu˘m “The Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People” of 1446 A History of the Korean Language Ki-Moon Lee S. Robert Ramsey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sa˜o Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521661898 # Cambridge University Press 2011 This publication is in copyright. -

A Fresh Look at the Sign System of the Braille Code" Analyzes

A Fresh Look at the Sign System of the Braille Code Eric P. Hamp and Hilda Caton Pamphlet File Research Library Running head: A Fresh Look at the Sign System 3 A Fresh Look at the Sign System The Authors Eric P. Hamp, Robert Maynard Hutchins Distinguished Service Professor of Linguistics and Behavioral Sciences, University of Chicago; Linguistic Consultant, Patterns: The Primary Braille Reading Program, American Printing House for the Blind. Hilda Caton, Project Director, Patterns: The Primary Braille Reading Program, American Printing House for the Blind; Associate Professor, Department of Special Education, University of Louisville. PampWet Fi» A Fresh Look at the Sign System 1 Abstract "A Fresh Look at the Sign System of the Braille Code" analyzes English braille as a written code from a linguistic viewpoint. The analysis was undertaken as a step toward teaching braille to young children. From the analysis a regrouping and fresh charac¬ terization of braille units evolved. This regrouping is discussed in the article proper and then presented in an outline. A Fresh Look at the Sign System 2 A Fresh Look at the Sign System of the Braille Code Background Reading has long been acknowledged to be a critical factor in the educational progress of children. The task of learning to read is never a simple one regardless of the medium through which the skill is acquired. However, children who read print have access to materials which are specifically designed to minimize the difficulties of the learning task. This is accompolished through the control and sequential presentation of vocabulary, the written or printed symbols, components of the reading skills, and concepts. -

Logography and Layering: a Functional Cross-Linguistic Analysis

This is a repository copy of Logography and layering: a functional cross-linguistic analysis. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/91110/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Tranter, N. (2013) Logography and layering: a functional cross-linguistic analysis. Written Language and Literacy, 16 (1). pp. 1-31. ISSN 1387-6732 https://doi.org/10.1075/wll.16.1.01tra Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Logography and layering A functional cross-linguistic analysis Nicolas Tranter University of Sheffield, United Kingdom This paper proposes a way in which the semantographic/phonographic dichotomy recognised as fundamental in logographic (or morphosyllabic) writing systems in East Asia, the ancient Middle East, and Mesoamerica, can be systematised to transcend the very different scholarly traditions in each region in order to allow valid and more meaningful cross-linguistic comparisons. -

Challenging the Dichotomy Between Phonography and Morphography: Transitions and Gray Areas

Challenging the Dichotomy Between Phonography and Morphography: Transitions and Gray Areas Sven Osterkamp · Gordian Schreiber Abstract. Traditionally, glottographic writing is divided into the two fundamen- tal categories of phonographic and (logo-, or increasingly) morphographic writ- ing, each with further more fine-grained subdivisions where necessary. In recent decades, various revisions to the earlier either/or approach have been proposed, leading to more flexible typological models that, e.g., allow for a mixture of dif- ferent types of phonography with different amounts of morphography in a given writing system. While it is thus common to acknowledge the mixed nature of writing systems as a whole, graphs or strings of graphs forming functional units (such as digraphs) are nevertheless typically assigned to either of the two basic typological categories. On closer scrutiny, however, there is an abundance of cases challenging this strict dichotomy on the level of graphs. Having reviewed the different notions of logo- or morphography found in the literature, this paper revisits the fundamental distinction between phonography and morphography in writing systems, drawing upon cases from the following areas: First, we will address transitions from morphograms to phonograms as well as from phonograms to morphograms. The dividing line between mor- phograms and phonograms is, however, not always easy to draw, thus leading us to gray areas and indeterminable cases. Finally, we will have a closer look at semantically motivated phonograms, as even in phonography the level of se- mantics is not necessarily irrelevant altogether. 1. Preliminaries In taxonomies of writing systems, so-called glottographic writing is commonly divided into phonography on the one hand and something else on the other that goes by several names, usually ‘logography’ (e.g., Sven Osterkamp 0000-0002-4596-9283 Ruhr University Bochum, Faculty of East Asian Studies, Universitätsstr. -

OG-Training-Manual-2019.Pdf

Jamey Peavler Therese Rooney ©2019 M.A. Rooney Foundation 9333 N Meridian Street, Suite 150 Indianapolis, IN 46260 317.571.2960 marooneyfoundation.org TABLE OF CONTENTS READING SCIENCE ....................................................................................................... 1 Important Terms ....................................................................................................................... 1 Reading Data ............................................................................................................................. 2 Cognitive Model ........................................................................................................................ 3 Development of the Three Cognitive Model Branches ............................................................ 4 WHAT IS ORTON-GILLINGHAM (OG)? ......................................................................... 5 History of the Approach ............................................................................................................ 5 Key Characteristics .................................................................................................................... 6 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT ........................................................................................ 7 Important Terms ....................................................................................................................... 7 Early Language Development ..................................................................................................