Reforming the Monetary System of Lebanon: a Prerequisite to Getting out of the Debt Trap - Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

May 5, 2006 Technical Revisions to the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement

May 5, 2006 Technical revisions to the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement The Foreign Exchange Committee (FXC), International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. (ISDA), and EMTA, Inc. announce two technical revisions to the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions (“2005 Supplement”). The first revision suggests how to incorporate into a Barrier or Binary Option Transaction the terms of the 2005 Supplement. The relevant Confirmation of the Barrier or Binary Option Transaction should state that “the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended by the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement, as published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc., EMTA, Inc., and the Foreign Exchange Committee are incorporated into this Confirmation.” For purposes of clarity, this provision has been added to Exhibits I and II to the 2005 Supplement, which illustrate how Barrier and Binary Options may be confirmed under the terms of the 2005 Supplement and the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions (“1998 Definitions”) (see the second paragraph and footnote 2 of each Exhibit). The revised Exhibits I and II are attached to this announcement. The second revision further describes the approach taken to the conventions for stating Currency Pairs in the Currency Pair Matrix that was published with the 2005 Supplement. The Matrix is provided as a best practice to facilitate the use of standard market convention when specifying the exchange rates relating to certain terms in a Confirmation of a Barrier or Binary Option Transaction that incorporates the provisions of the 2005 Supplement. The introductory statement to the Matrix has been revised to highlight that its conventions for stating currency pairs may be different from trading conventions. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

E Near East Forestry and Range Commission (NEFRC) Will Be Held in Beirut, Lebanon, from 11 to 14 December 2017

December 2017 FO:NEFRC/2017/Inf.1 E NEAR EAST FORESTRY AND RANGE COMMISSION TWENTY-THIRD SESSION Beirut, Lebanon, 11 - 14 December 2017 INFORMATION NOTE I. DATES AND VENUE 1. The Twenty-third session of the Near East Forestry and Range Commission (NEFRC) will be held in Beirut, Lebanon, from 11 to 14 December 2017. 2. The official opening ceremony of the NEFRC will take place at 09:00 a.m. on Monday, 11 December 2017. 3. The event will take place in Raouche Arjaan by Rotana Hotel, in Beirut. 4. The Raouche Arjaan by Rotana Hotel is located in the heart of Beirut, 10 minute walk from the Lebanese American University, Chouran Beirut, Lebanon; Tel: 00 961 (0) 1 781111; Fax: 00 961 (0) 1 782222. Email: [email protected] II. LANGUAGES 5. Simultaneous interpretation will be provided in Arabic and English. III. DOCUMENTATION 6. The commission documents will be made available to participants in Arabic, English and French. They will be sent out before the sessions and posted on the NEFRC Commission website: http://www.fao.org/forestry/31112/en/. Delegates are kindly requested to take their own documents to the meeting since very few copies will be available during the sessions. This document is printed in limited numbers to minimize the environmental impact of FAO's processes and contribute to climate neutrality. Delegates and observers are kindly requested to bring their copies to meetings and to avoid asking for additional copies. Most FAO meeting documents are available on the Internet at www.fao.org 2 FO:NEFRC/2017/Inf.1 IV. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

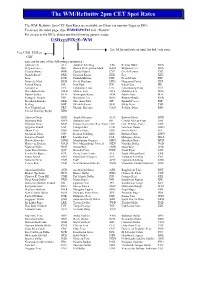

WM/Refinitiv 2Pm CET Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv 2pm CET Spot Rates The WM/ Refinitiv 2pm CET Spot Rates are available on Eikon via monitor Pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRESPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes : USDxxxFIXzE=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR or GBP xxx can be any of the following currencies : Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy Ariary -

The Lebanese Republic Global Medium Term Note Program

U.S. $13,500,000,000 The Lebanese Republic Global Medium Term Note Program Under this U.S. $13,500,000,000 Global Medium Term Note Program (the "Program"), the Lebanese Republic (the "Republic") may, from time to time, subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, issue notes in either bearer or registered form (the "Notes"). The maximum aggregate principal amount of all Notes from time to time outstanding under the Program will not exceed U.S. $13,500,000,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies determined at the time of the agreement to issue), subject to any duly authorized increase. The Notes may be denominated in U.S. Dollars, euro and such other currencies as may be agreed between the Republic and the relevant Dealers (as defined below). The Notes will have maturities of not less than three months nor more than 30 years and will bear interest on a fixed or floating rate basis. Attention is drawn to the limitations and qualifications regarding the description of the economic situation in the Republic appearing on page 8 of this Offering Circular. This Offering Circular supersedes all prior Offering Circulars relating to the Program. Any Notes to be issued after the date hereof under the Program are issued subject to the provisions set out herein. This does not affect any Notes issued prior to the date hereof. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to the Dealers and any additional Dealer(s) appointed under the Program from time to time pursuant to the terms of a Program Agreement dated March 8, 1999 (as the same may be amended from time to time, the "Program Agreement"), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis (each, a "Dealer" and, together, the "Dealers"). -

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name*

FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Afghanistan AFA Afghani Albania ALL Lek Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Amer Samoa USD US Dollar Andorra ADP Andorran Peseta Angola AON New Kwanza Anguilla XCD East Caribbean Dollar Antigua Barb XCD East Caribbean Dollar Argentina ARS Argentine Peso Armenia AMD Armeniam Dram Aruba AWG Aruban Guilder Australia AUD Australian Dollar Austria ATS Schilling Azerbaijan AZM Azerbaijanian Manat Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahrain BHD Bahraini Dinar Bangladesh BDT Taka Barbados BBD Barbados Dollar Belarus BYB Belarussian Ruble Belgium BEF Belgian Franc Belize BZD Belize Dollar Benin XOF CFA Franc Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Bhutan BTN Ngultrum Bolivia BOB Boliviano Botswana BWP Pula Br Ind Oc Tr USD US Dollar Br Virgin Is USD US Dollar Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Brunei Darsm BND Brunei Dollar Bulgaria BGN New Lev Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Côte dIvoire XOF CFA Franc Cambodia KHR Riel Cameroon XAF CFA Franc Canada CAD Canadian Dollar Cape Verde CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cayman Is KYD Cayman Islands Dollar Cent Afr Rep XAF CFA Franc Chad XAF CFA Franc Channel Is GBP Pound Sterling Chile CLP Chilean Peso China CNY Yuan Renminbi China, Macao MOP Pataca China,H.Kong HKD Hong Kong Dollar China,Taiwan TWD New Taiwan Dollar Christmas Is AUD Australian Dollar Cocos Is AUD Australian Dollar Colombia COP Colombian Peso Comoros KMF Comoro Franc FAO Country Name ISO Currency Code* Currency Name* Congo Dem R CDF Franc Congolais Congo Rep XAF CFA Franc Cook Is NZD New Zealand Dollar Costa Rica -

Economic Consequences of the War in Lebanon

Papers on Lebanon 3 Economic Consequences of the War in Lebanon DR. NASSER H. SAID1 - ___--- ----. ----- ----. -- -1-71.- -.--- - Centre for Lebanese Studies -- =--i - -- 59 Observatory Street, Oxford OX2 6EP. Tel: (0865) 58465 September 1986 Nasser Saidi has taught macroeconomics and international economics at The University of Chicago (1977-80), the Graduate Institute of International Studies and the University of Geneva (1981-85). He is a consultant to governments, central banks and international financial organisations, in work relating to Latin America and the Middle East. He is the author of numerous articles and studies in theoretical and applied international macroeconomics, and of "Essays in Rational Expectations and Flexible Exchange Rates", (1981). 1. Introduction 1.1This paper examines the consequences of Lebanon's prolonged war for the economy and its immediate future prospects. Currently, Lebanon is entering a state of severe economic depression and poverty, accompanied by a sharply accelerating inflation rate. The most visible symptom of the underlying state of the economy and its alarming monetary and financial conditions is the depreciation of the Lebanese Pound against all major currencies. The paper contends that - given the impact of the war on the productive capacity of the economy - it is the explosive state of public finance that is leading the country to hyperinflation and an accelerated depreciation rate for the Lebanese Pound. 1.2 The main results and conclusions of this paper are stated below - with the supporting analysis developed in the main body of the paper. The major consequences of the war in Lebanon are: (9 A sharp reduction in the level and growth rate of domestic production and income, accompanied by an even sharper reduction in investment spending. -

Exchange Rate Statistics January 2017

Exchange rate statistics January 2017 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2017 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Tel +49 69 9566-0 or +49 69 9566 8604 Fax +49 69 9566 8606 or 3077 The Statistical Supplement Exchange rate statistics is published by the Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt am http://www.bundesbank.de Main, by virtue of section 18 of the Bundesbank Act. It is available to interested parties free of charge. Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistical data, supplementing the Monthly Report, The German-language version of the Statis tical Supple- can be found in the follow ing supplements. ment Exchange rate statistics is published quarterly in printed form. The Deutsche Bundesbank also publishes an Banking statistics monthly updated monthly edition in German and in English on its Capital market statistics monthly website. In cases of doubt, the original German-language Balance of payments statistics monthly version is the sole authoritative text. Seasonally adjusted business statistics monthly ISSN 2190–8990 (online edition) Selected updated statistics are also available on the Cut-off date: 10 January 2017. website. Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics January 2017 3 Contents I Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1 Euro-area member states and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2 Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II Euro foreign exchange reference rates of the European Central Bank 1 Daily rates . -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc.