From Playboys to Disco Pigs: Irish Identities on a World Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enda Walsh's the Walworth Farce

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Jordan, Eamonn “STUFF FROM BACK HOME:” ENDA WALSH’S THE WALWORTH FARCE Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 333-356 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696016 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative "Stuff from Back Home:"... 333 “STUFF FROM BACK HOME:”1 ENDA WALSH’S THE WALWORTH FARCE Eamonn Jordan University College Dublin Abstract: Since its first performance in 2006 by Druid Theatre Company, Enda Walsh’s award-winning The Walworth Farce has toured Ireland, Britain, America, Canada, New Zealand and Australia to great acclaim, with the brilliance of the directing, design and acting engaging with the intelligence and theatricality of Walsh’s script. The play deals with a family, who as part of a daily enforced ritual, re-enact a farce, written and directed by Dinny, the patriarch, a story which accounts for their exile in London, and away from their family home in Cork. Their enactment is an attempt to create a false memory, for their performance is very much at odds with the real events which provoked their exile. Keywordsds: Enda Walsh, The Walworth Farce, Druid Theatre, Farce, Performance, Diasporic. -

A Coping Strategy

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Memory In Contemporary Irish Drama“ Verfasserin Stefanie Nestreba angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 020 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: UF Englisch 344, UF Kath. Religion 020 Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Werner Huber ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to all those people who have supported me in the course of my studies and during the writing process of this diploma thesis. First, I owe my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Dr. Werner Huber, since this thesis would not have been possible unless he had raised my interest in the subject area of Irish Literature. I am particularly grateful to Prof. Dr. Werner Huber for all his words of advice, encouragement and guidance. I would also like to show my gratitude to my teachers, in particular to my teacher from elementary school, Maria Rudolph, whose way of teaching has inspired me to pursue the profession of a teacher myself. Furthermore, I am heartily thankful to my friends, especially to Manuela Kopper, who has been my personal motivational coach and has emotionally supported me throughout the working process of this thesis. I would like to thank my dear friend, Nicky Sells from England. Her careful reading and her constructive commenting on the drafts of this thesis deserve my sincere thanks. Moreover, it is a pleasure to thank my fiancé, Thomas Buchgraber, for his patience and motivation. It was his challenging task to motivate me, listen to me patiently and endure all my good and bad times. -

Redalyc.CONTEMPORARY IRISH THEATRE

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Kopschitz X. Bastos, Beatriz; O’Shea, José Roberto CONTEMPORARY IRISH THEATRE: A DYNAMIC COLLECTION OF CRITICAL VOICES Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 58, enero-junio, 2010, pp. 11-22 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348696001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Contemporary Irish Theatre... 11 CONTEMPORARY IRISH THEATRE: A DYNAMIC COLLECTION OF CRITICAL VOICES The current issue of Ilha do Desterro explores aspects of contemporary Irish theatre, within the island of Ireland and in its international contexts, after 1950: this is the first publication in Brazil dedicated specifically to critical contribution in this field. The articles by scholars and theatre practitioners from various countries apart from Brazil and Ireland, such as The United States, France, Italy, Germany, and the Czech Republic, address the work of individual writers as well of theatre groups, considering textual and performance practices, most of them not confined to the areas of theatre and literature, but including considerations on other fields of knowledge such as politics, economics, history, philosophy, media and film studies, arts and psychology. Carefully and passionately written, the texts feature a variety of theoretical frameworks and research methods. -

Enda Walsh's Disco Pigs (1997), the New Electric Ballroom (2004) and the Walworth Farce (2006)

First time tragedy, second time farce: Enda Walsh©s Disco pigs (1997), The New Electric Ballroom (2004) and The Walworth farce (2006) Article (Published Version) McEvoy, William (2014) First time tragedy, second time farce: Enda Walsh's Disco pigs (1997), The New Electric Ballroom (2004) and The Walworth farce (2006). C21: Journal of 21st-century Writings, 3 (1). pp. 1-17. ISSN 2045-5216 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/53493/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bc. Zuzana Neubauerová Violence in Contemporary Irish Drama: Martin McDonagh, Enda Walsh and Mark O’Rowe Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph.D. Olomouc 2018 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne: Podpis: …............................... Acknowledgements I would like to thank Mgr. David Livingstone, Ph. D. for his patience, help, support and valuable advice. Content 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………….……….5 2. Historical and Cultural Background…………………………………………………7 2.1. The ‘Revolution’ of the 1990s.…………………………………………….9 3. The Development of Irish Theatre since The Abbey……………………………….13 3.1. Themes and Tendencies in Contemporary Irish Drama………….……….15 4. A History of Violence in Drama……………………………………………………19 4.1. Violence on the Irish Stage………………………………………….……23 5. Martin McDonagh………………………………………………………………….26 5.1. The Irish Plays……………………………………………………………28 5.2. The Pillowman……………………………………………………………31 5.3. Offstage Violence…………………………………………………………31 5.4. Multiplied Violence……………………………………………………….34 5.5. Onstage Violence...….……………………………………………………36 5.6. The First Duty of a Storyteller Is to Tell a Story………………………….39 6. Enda Walsh…………………………………………………………………………42 6.1. Disco Pigs and The Walworth Farce……………………………………...44 6.2. Brutal Words...……………………………………………………………46 6.3. Brutal Deeds…...………………………………………………………….48 -

The Walworth Farce

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS CAST Wednesday, November 18, 2009, 8pm The Walworth Farce Thursday, November 19, 2009, 8pm Friday, November 20, 2009, 8pm Saturday, November 21, 2009, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, November 22, 2009, 3pm Zellerbach Playhouse Druid Ireland The Walworth Farce by Enda Walsh Robert Day Robert CAST Dinny Michael Glenn Murphy Sean Tadhg Murphy Blake Raymond Scannell Hayley Mercy Ojelade CREATIVE TEAM Writer Enda Walsh Director Mikel Murfi Set and Costume Designer Sabine Dargent Lighting Designer Paul Keogan Casting Director Maureen Hughes Robert Day Robert CREW Artistic Director Garry Hynes Production Manager Eamonn Fox Technical Manager Barry O’Brien Druid is grant-aided by the Arts Council of Ireland and gratefully acknowledges the support of Company Stage Manager Sarah Lynch Culture Ireland for funding its international touring program. Druid wishes to express its Stage Manager Paula Tierney continuing gratitude to Thomas McDonogh & Company Ltd for their support of the company and to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Galway City Council and Galway County Council. Master Carpenter Gus Dewar Costume Supervisor Doreen McKenna Wigs and Make-up Val Sherlock The Walworth Farce was commissioned by Druid and received its world Cal Performances’ 2009–2010 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. premiere at the Town Hall Theatre, Galway, on March 20, 2006. 4 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 5 PROGRAM NOTES ABOUT THE ARTISTS THE WALWORTH FARCE STORY COMPANY • Through its new writing program, Druid nurtures and supports new play- ydney, -

The Beauty Queen of Leenane

The Beauty Queen of Leenane A production of Druid Martin McDonagh Writer Garry Hynes Director Thursday Evening, March 9, 2017 at 7:30 Friday Evening, March 10, 2017 at 8:00 Saturday Evening, March 11, 2017 at 8:00 Power Center Ann Arbor 42nd, 43rd, and 44th Performances of the 138th Annual Season International Theater Series Friday evening’s presenting sponsor is Emily Bandera. Saturday evening’s supporting sponsor is the The James Garavaglia Theater Endowment Fund. Funded in part by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Endowment Fund at UMS. Special thanks to Zoey Bond for her participation in events surrounding this week’s performances. Special thanks to Tiffany Ng, assistant professor of carillon and university carillonist, for coordinating the pre-performance music on the Charles Baird Carillon. Druid appears by arrangement with David Eden Productions, Ltd. Druid gratefully acknowledges the support of the Arts Council of Ireland and Culture Ireland. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. CAST Ray Dooley / Aaron Monaghan Mag Folan / Marie Mullen Pato Dooley / Marty Rea Maureen Folan / Aisling O’Sullivan CREATIVE TEAM Writer / Martin McDonagh Director / Garry Hynes Set and Costume Design / Francis O'Connor Lighting Design / James F. Ingalls This evening’s performance is approximately two hours and 15 minutes in duration and is performed with one intermission. Following Thursday evening’s performance, please feel free to remain in your seats and join us for a post-performance Q&A with members of the company. -

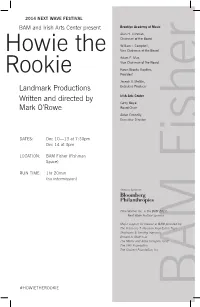

Howie the Rookie

2014 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL BAM and Irish Arts Center present Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Howie the Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, Rookie President Joseph V. Melillo, Landmark Productions Executive Producer Written and directed by Irish Arts Center Gerry Boyle, Mark O’Rowe Board Chair Aidan Connolly, Executive Director DATES: Dec 10—13 at 7:30pm Dec 14 at 3pm LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) RUN TIME: 1hr 20min (no intermission) Season Sponsor: Time Warner Inc. is the BAM 2014 Next Wave Festival Sponsor Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen Jr. The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc #HOWIETHEROOKIE BAM Fisher 2014 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL Howie the Rookie HAIR AND MAKE-UP WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY Val Sherlock Mark O’Rowe PUBLICIST THE HOWIE LEE / THE ROOKIE LEE Sinéad O’Doherty | Gerry Lundberg PR Tom Vaughan-Lawlor PHOTOGRAPHER SET AND COSTUME DESIGN BY Patrick Redmond Paul Wills GRAPHIC DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGN BY Gareth Jones Sinéad McKenna AMERICAN STAGE MANAGER SOUND DESIGN BY R. Michael Blanco Philip Stewart PRODUCER Anne Clarke ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Sara Cregan PRODUCTION MANAGER Eamonn Fox STAGE DIRECTOR Presented in association with Clive Welsh David Eden Productions Ltd., with the support of Culture Ireland. ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Sarah Baxter The actor appears with the permis- sion of Actors’ Equity Association. The ASSISTANT DESIGNER American stage manager is a member Adrian Gee of Actors’ Equity Association. -

Eamonn Jordan University College Dublin

"Stuff from Back Home:"... 333 “STUFF FROM BACK HOME:”1 ENDA WALSH’S THE WALWORTH FARCE Eamonn Jordan University College Dublin Abstract: Since its first performance in 2006 by Druid Theatre Company, Enda Walsh’s award-winning The Walworth Farce has toured Ireland, Britain, America, Canada, New Zealand and Australia to great acclaim, with the brilliance of the directing, design and acting engaging with the intelligence and theatricality of Walsh’s script. The play deals with a family, who as part of a daily enforced ritual, re-enact a farce, written and directed by Dinny, the patriarch, a story which accounts for their exile in London, and away from their family home in Cork. Their enactment is an attempt to create a false memory, for their performance is very much at odds with the real events which provoked their exile. Keywordsds: Enda Walsh, The Walworth Farce, Druid Theatre, Farce, Performance, Diasporic. First performed on 20 March 2006 at the Town Hall Theatre in Galway, and produced by Druid Theatre Company, Enda Walsh’s The Walworth Farce went on a national tour and from there opened with some cast changes on 5 August 2007 at the Traverse Theatre in Ilha do Desterro Florianópolis nº 58 p. 333-356 jan/jun. 2010 334 Eamonn Jordan Edinburgh where it won a Festival Fringe First Award. (Garrett Lombard played Blake, Denis Conway took the role of the father of the family, Dinny, Aaron Monaghan performed as Sean, and in its current run, Tadhg Murphy replaced Monaghan and Hayley was originally played by Syan Blake and in 2008 by Mercy Ojelade and in between both by Natalie Best). -

Paul Howard 8

Landmark Productions ROSS O’CARROLL-KELLY Postcards from the Ledge Broadcast live from Mermaid Arts Centre, Bray Saturday 15 May, 2021 1 On-Demand 16–23 May, 2021 Contents Landmark Productions 4 The Hook, Lyon and Sinker Guide to Estate Agent Jargon 6 Paul Howard 8 Ross O’Carroll-Kelly 10 Rory Nolan 11 The Ledge Writ Lorge 12 Jimmy Fay 14 Grace Smart 15 POST-SHOW TALK Credits 16 with Paul Howard and Rory Nolan Paul Keogan 18 Denis Clohessy 19 in conversation with Ross O’Carroll-Kelly: The Stage Years 20 Irish Times columnist Róisín Ingle Thanks 22 As part of Live Broadcast and available on-demand Join The Conversation 24 BOOK WITH YOUR SHOW TICKET OR BUY SEPARATELY HERE 2 3 Landmark Productions Producer Landmark Productions ROSS O’CARROLL-KELLY Postcards from the Landmark Productions is one of Ireland’s It produces a wide range of ambitious leading theatre producers. It produces work – plays, operas and musicals – in wide-ranging work in Ireland, and shares theatres ranging from the 66-seat New that work with international audiences. Theatre to the 1,254-seat Olympia. It Ledge co-produces regularly with a number of Earlier this year it launched Landmark partners, including, most significantly, Live, a new online streaming platform Galway International Arts Festival and Irish by Paul Howard to enable the company to bring the National Opera. Its 18 world premieres thrill of live theatre to audiences around include new plays by major Irish writers Director the world. Postcards from the Ledge is such as Enda Walsh and Mark O’Rowe, the third production to be streamed to featuring a roll-call of Ireland’s finest Jimmy Fay date. -

Druidshakespeare: the History Plays by William Shakespeare, Adapted by Mark O’Rowe

Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 7 –19 Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College Druid Theatre Company DruidShakespeare: The History Plays By William Shakespeare, adapted by Mark O’Rowe DruidShakespeare: Part 1 Richard II; and Henry IV, Part I (Approximately 3 hours 25 minutes, including one intermission) July 7, 9, 14, 16 DruidShakespeare: Part 2 Henry IV, Part II; and Henry V (Approximately 2 hours 45 minutes, including one intermission) July 8, 10, 15, 17 Marathon Parts 1 and 2 in a single day (Approximately 6 hours 55 minutes, including three intermissions) July 11, 12, 18, 19 Director Garry Hynes Sound Design Gregory Clarke Associate Director, Design Francis O’Connor Music Conor Linehan Associate Director, Movement David Bolger Dramaturg Thomas Conway Co-Costume Designer Doreen McKenna Voice Coach Andrew Wade Lighting Design James F. Ingalls Fight Director Donal O’Farrell Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of DruidShakespeare: The History Plays is made possible in part by generous support from the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and Jennie and Richard DeScherer. Additional support is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Druid Theatre Company’s visit to Lincoln Center Festival is made possible with the support of Culture Ireland. -

“The Lost and the Lonely”: Crisis in Three Plays by Enda Walsh

Études irlandaises 40-2 | 2015 La crise ? Quelle crise ? “The Lost and the Lonely”: Crisis in Three Plays by Enda Walsh Patrick Lonergan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/4743 DOI: 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.4743 ISSN: 2259-8863 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2015 Number of pages: 137-154 ISBN: 978-2-7535-4366-9 ISSN: 0183-973X Electronic reference Patrick Lonergan, « “The Lost and the Lonely”: Crisis in Three Plays by Enda Walsh », Études irlandaises [Online], 40-2 | 2015, Online since 11 January 2016, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/4743 ; DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.4743 © Presses universitaires de Rennes “he Lost and the Lonely”: Crisis in hree Plays by Enda Walsh Patrick Lonergan National University of Ireland, Galway Abstract This article explores the theme of crisis in three plays by Enda Walsh: Penelope (2010), The New Electric Ballroom (2008) and The Walworth Farce (2006). By showing how Penelope directly addressed the collapse of the Celtic Tiger, the article identifies major themes that can help to understand Walsh’s work more generally. This is demonstrated by a discussion of the other two plays, which are placed in the context of events in Ireland before and after the col- lapse of its Celtic Tiger in 2008. Keywords: Enda Walsh, Druid Theatre, Celtic Tiger, Magdelene Laundries, The Odyssey, Emigration, Multiculturalism, Irish Theatre, Irish Culture Résumé Cet article explore le theme de la crise dans trois pieces d’Enda Walsh: Penelope (2010), The New Electric Ballroom (2008) et The Walworth Farce (2006).