Wings 2007 Fall Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

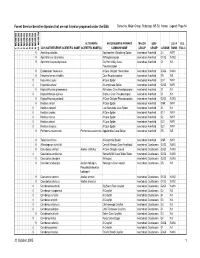

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

Papilio Series) @17 2006

(NEW April 28 PAPILIO SERIES) @17 2006 PROPOSALS FOR A NEW INSECT STUDY, COMMERCE, AND CONSERVATION LAW THAT DEREGULATES DEAD INSECTS, AND PROPOSALS FOR FIXING THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AS APPLIED TO INSECTS By Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes St., Lakewood, Colorado, 80226 (Ph.D. in entomology, University of California, Berkeley) Why Do We Need New Insect Laws? The current laws regulating insects (and plants) in the U.S. are very bad. They were made for deer, and are only incidentally being applied to insects, because no legislators ever thought to make laws specifically targeted at insects that are not agricultural pests. These laws are not serving the conservation of insects well, and the laws are retarding the taxonomic study of insects, and are making criminals out of harmless hobbyist insect collectors. Basically, large animals like deer and Bighorn Sheep can be managed by controlling the numbers hunted using bag limits and exclusion areas etc., and roping and corraling them and transporting them to new sites. Large animals tend to have low population numbers, so might need to be protected from hunting (after all, at the end of the shooting spree in the late 1800s, the U.S. reached a low of population numbers for Bison and deer and nearly every other large animal, and their numbers have gradually recovered since). But insects are tiny by comparison, and their population sizes are huge by comparison. The average insect may be a thousand or a million times more numerous than your average deer'. Insect population sizes cannot be "managed" like deer, because population sizes vary hugely mostly depending on the weather and other uncontrollable factors, and their survival depends on the continued survival of their habitat, rather than useless government intervention. -

Effects of Climate Change on Arctic Arthropod Assemblages and Distribution Phd Thesis

Effects of climate change on Arctic arthropod assemblages and distribution PhD thesis Rikke Reisner Hansen Academic advisors: Main supervisor Toke Thomas Høye and co-supervisor Signe Normand Submitted 29/08/2016 Data sheet Title: Effects of climate change on Arctic arthropod assemblages and distribution Author University: Aarhus University Publisher: Aarhus University – Denmark URL: www.au.dk Supervisors: Assessment committee: Arctic arthropods, climate change, community composition, distribution, diversity, life history traits, monitoring, species richness, spatial variation, temporal variation Date of publication: August 2016 Please cite as: Hansen, R. R. (2016) Effects of climate change on Arctic arthropod assemblages and distribution. PhD thesis, Aarhus University, Denmark, 144 pp. Keywords: Number of pages: 144 PREFACE………………………………………………………………………………………..5 LIST OF PAPERS……………………………………………………………………………….6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………...7 SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………………………...8 RESUMÉ (Danish summary)…………………………………………………………………....9 SYNOPSIS……………………………………………………………………………………....10 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………...10 Study sites and approaches……………………………………………………………………...11 Arctic arthropod community composition…………………………………………………….....13 Potential climate change effects on arthropod composition…………………………………….15 Arctic arthropod responses to climate change…………………………………………………..16 Future recommendations and perspectives……………………………………………………...20 References………………………………………………………………………………………..21 PAPER I: High spatial -

Papilio 0 0000 ..;)

1 NEW :ft{t 2 Nov. 15,1982 SERIES • $1.50 PAPILIO 0 0000 ..;) THE Lil'E HISTORY AND l!XlOLOGY f!F AN ALPINE RELICT, BOLORIA !MFR.OBA ACROCNEMA (LEPIDOP.rEltA: NYMPHALIDAE), ILLUSTRATING A NE.W MATHEMATICAL POPULATION CENSUS MEl'HOD Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes St., Lakewood, Colorado, 80226 Abstract. The egg, larva, and pupa of B. improba acrocnema are described and illustrated. The larval foodplant Is Salix nivalis. There are five instars; overwintering occurs in the fourth instar, and perhaps also in the first instar. Adults fly slowly near the ground, and are very local. Males patrol to find females. Adults often visit flowers, and bask on dark soil by spreading the wings laterally. A binomial method is derived and used to determine daily population size. Daily population size may be as large as 655, and yearly population size may reach two thousand in a few hectares. Introduction Boloria improba (Butl.) is a circumpolar butterfly, occurring from northern Scandinavia eastward to northern Siberia and arctic America. In North America it occurs from Alaska to Baffin r., south to central Alberta, and a relict subspecies acrocnema G. & s. occurs in the alpine San Juan Mts. of Colorado. The life history and ecology of improba were nearly unknown. This paper presents the complete life history and details of the. life cycle, ecology, and behavior, studied from 1979 to 1981. In addition, a new method of computing the population size of one continuous mark recapture sample is presented, which is useful for quick survey work on colonial animals like insects. -

Behavioural Thermoregulation by High Arctic Butterflies*

Behavioural Thermoregulation by High Arctic Butterflies* P. G. KEVAN AND J. D. SHORTHOUSE2s ABSTRACT. Behavioural thermoregulation is an important adaptation of the five high arctic butterflies found at Lake Hazen (81 “49‘N., 71 18’W.), Ellesmere Island, NorthwestTerritories. Direct insolation is used byarctic butterflies to increase their body temperatures. They select basking substrates andprecisely orientate their wings with respect to the sun. Some experiments illustrate the importance of this. Wing morphology, venation, colour, hairiness, and physiology are briefly discussed. RI~SUMÉ.Comportement thermo-régulatoire des papillons du haut Arctique. Chez cinq especes de papillons trouvés au lac Hazen (81”49’ N, 71” 18’ W), île d’Elles- mere, Territoires du Nord-Ouest, le comportement thermo-régulatoire est une im- portante adaptation. Ces papillons arctiques se servent de l’insolation directe pour augmenter la température de leur corps: ils choisissent des sous-strates réchauffantes et orientent leurs ailes de façon précise par rapport au soleil. Quelques expériences ont confirmé l’importance de ce fait. On discute brikvement de la morphologie alaire, de la couleur, de la pilosité et de la physiologie de ces insectes. INTRODUCTION Basking in direct sunlight has long been known to have thermoregulatory sig- nificance for poikilotherms (Gunn 1942), particularly reptiles (Bogert 1959) and desert locusts (Fraenkel 1P30;.Stower and Griffiths 1966). Clench (1966) says that this was not known before iwlepidoptera but Couper (1874) wrote that the common sulphur butterfly, Colias philodice (Godart) when resting on a flower leans sideways “as if to receive the warmth of the sun”. Later workers, noting the consistent settling postures and positions of many butterflies, did not attribute them to thermoregulation, but rather to display (Parker 1903) or concealment by shadow minimization (Longstaff 1905a, b, 1906, 1912; Tonge 1909). -

Papilio (New Series) #1, P

NEW c;/;::{J:, 11 Feb. 20, 1998 PAPILIO SERIES qj::f? $1.00 NEWWESTERN NORTH AMERICAN BUTT£RFLl£S BY DR, JAMES A, SCOTT 60 Estes Street, Lakewood, Colorado 80226, and one taxon by MICHAEL S, FISHER 6521 S. Logan Street, Littleton, Colorado 80121 Abstract. New subspecies and other geographic tax.a from western U.S. are described and named. INTRODUCTION Scott (1981) named various new subspecies of butterflies from western U.S. Since then a few other butterflies have come to my attention that deserve to be named. They are named below. NEWTAXA HIPPARCHIA (NEOMINOIS) RIDINfiSII WYOMIN60 SCOTI 1998, NEW SUBSPECIES (OR SPECIES?) (Figs 1-2) DIAGNOSIS. This subspecies is distinguished by its very late flight, L Aug. to M Sept., versus June fer ordinary ridingsii (Edwards), and by its mate-locating behavior (at least in central Wyoming including the type locality), in which males perch in swales in early morning to await females, versus ridgetops for ordinary ridingsii. This butterfly is not a freak late-season occurrence; it flies every year, is very widespread in distribution, and around the end of August it is the commonest butterfly in Wyoming (except perhaps Hesperia comma). I examined valvae of this ssp. and June ridingsii, and the first few comparison pairs of examined males had a different curl on one dorsal shoulder of the valva, but as more additional males were examined, some were found to have the shape of the other, and after a dozen males of wyomingo were examined and compared to a dozen June ridingsii, it appeared that this trait was sufficiently variable that it is not a consistent difference. -

Butterflies and Moths of Yukon-Koyukuk, Alaska, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

Insect Pollinators of Gates of the Arctic NPP a Preliminary Survey of Bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) and Flower Flies (Diptera: Syrphidae)

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Insect Pollinators of Gates of the Arctic NPP A Preliminary Survey of Bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) and Flower Flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) Natural Resource Report NPS/GAAR/NRR—2017/1541 ON THE COVER Left to right, TOP ROW: Bumble bee on Hedysarum, Al Smith collecting bees at Itkillik River; MIDDLE ROW: Al Smith and Just Jensen collecting pollinators on Krugrak River, Andrena barbilabris on Rosa; BOTTOM ROW: syrphid fly on Potentilla, bee bowl near Lake Isiak All photos by Jessica Rykken Insect Pollinators of Gates of the Arctic NPP A Preliminary Survey of Bees (Hymenoptera: Anthophila) and Flower Flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) Natural Resource Report NPS/GAAR/NRR—2017/1541 Jessica J. Rykken Museum of Comparative Zoology Harvard University 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

Fritillary, White Mountain

Appendix A: Insects White Mountain Fritillary Boloria titania montinus Federal Listing N/A State Listing E Global Rank State Rank S1 Regional Status Photo by © K.P. McFarland Justification (Reason for Concern in NH) White Mountain fritillary is limited to the 2,800 ac alpine zone of the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF). The natural communities used most frequently by White Mountain fritillary ranked S1 in New Hampshire. Climate change will likely alter alpine habitat structure, composition, phenology, and distribution, all of which directly impact White Mountain fritillary populations (Kimball and Weihrauch 2000, McFarland 2003, Lesica and McCune 2004). Habitat isolation further increases the species’ vulnerability (Halloy and Mark 2003, McFarland 2003). Interdependent responses to climate change could disrupt ecological interactions throughout the alpine community, reducing the ability of sensitive species to endure other environmental stresses, such as acid deposition and increased UV‐B radiation (McCarty 2001). Distribution White Mountain fritillary is a subspecies endemic to the 2,800 ac alpine zone of the Presidential Range of the WMNF (McFarland 2003). Habitat suitability depends on the abundance of host plants, particularly Alpine goldenrod, as well as ground temperature, moisture, and winter snow cover (Anthony 1970, McFarland 2003). White Mountain fritillary populations tend to be locally abundant, the northernmost occurrence is from Mt. Madison and the southernmost is Mt. Pierce at an elevation range of 1,220 to 1,860 m, with the highest densities at Cragway Spring and Wamsutta Trail (McFarland 2003). The only historical record occurring outside the Presidential Range alpine zone was a specimen collected by D. J. -

Book Review, of Systematics of Western North American Butterflies

(NEW Dec. 3, PAPILIO SERIES) ~19 2008 CORRECTIONS/REVIEWS OF 58 NORTH AMERICAN BUTTERFLY BOOKS Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes Street, Lakewood, Colorado 80226-1254 Abstract. Corrections are given for 58 North American butterfly books. Most of these books are recent. Misidentified figures mostly of adults, erroneous hostplants, and other mistakes are corrected in each book. Suggestions are made to improve future butterfly books. Identifications of figured specimens in Holland's 1931 & 1898 Butterfly Book & 1915 Butterfly Guide are corrected, and their type status clarified, and corrections are made to F. M. Brown's series of papers on Edwards; types (many figured by Holland), because some of Holland's 75 lectotype designations override lectotype specimens that were designated later, and several dozen Holland lectotype designations are added to the J. Pelham Catalogue. Type locality designations are corrected/defined here (some made by Brown, most by others), for numerous names: aenus, artonis, balder, bremnerii, brettoides, brucei (Oeneis), caespitatis, cahmus, callina, carus, colon, colorado, coolinensis, comus, conquista, dacotah, damei, dumeti, edwardsii (Oarisma), elada, epixanthe, eunus, fulvia, furcae, garita, hermodur, kootenai, lagus, mejicanus, mormo, mormonia, nilus, nympha, oreas, oslari, philetas, phylace, pratincola, rhena, saga, scudderi, simius, taxiles, uhleri. Five first reviser actions are made (albihalos=austinorum, davenporti=pratti, latalinea=subaridum, maritima=texana [Cercyonis], ricei=calneva). The name c-argenteum is designated nomen oblitum, faunus a nomen protectum. Three taxa are demonstrated to be invalid nomina nuda (blackmorei, sulfuris, svilhae), and another nomen nudum ( damei) is added to catalogues as a "schizophrenic taxon" in order to preserve stability. Problems caused by old scientific names and the time wasted on them are discussed. -

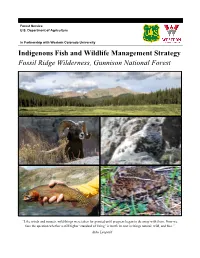

Fossil Ridge Wilderness Indigenous Fish And

a Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture In Partnership with Western Colorado University Indigenous Fish and Wildlife Management Strategy Fossil Ridge Wilderness, Gunnison National Forest “Like winds and sunsets, wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them. Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free.” – Aldo Leopold Indigenous Fish and Wildlife Management Strategy Fossil Ridge Wilderness, Gunnison National Forest Tobias Nickel Wilderness Fellow Master in Environmental Management (MEM) Candidate [email protected] October 2020 Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests Gunnison Ranger District 216 N. Colorado St. Gunnison, CO 81230 Western Colorado University The Center for Public Lands 1 Western Way Gunnison, CO 81231 ON THE FRONT COVER Top: Henry Mountain, the highest point in the wilderness at 13,254 feet, as seen from an expansive, subalpine grassland meadow along the Van Tuyl Trail (Tobias Nickel, July 4, 2020) Middle left: Bighorn ram (CPW) Middle right: Southern white-tailed ptarmigan in fall plumage (Shawn Conner, BIO-Logic, Inc.) Bottom left: Colorado River cutthroat trout (Photo © Alyssa Anduiza, courtesy of Aspiring Wild) Bottom right: Adult boreal toad (Brad Lambert, CNHP) ON THE BACK COVER The shores of Henry Lake in the heart of the Fossil Ridge Wilderness. Rising to over 13,000 feet, the granite peaks of the Fossil Ridge tower in the background (Tobias Nickel, June 16, 2020) ii iii Dedication This publication is dedicated to all past, present, and future defenders of wilderness. Your efforts safeguard the Earth’s wild treasures from our species’ most destructive tendencies and demonstrate that humility and restraint are possible in an age of overconsumption and unfettered development.