Papilio (New Series) #1, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

Papilio Series) @17 2006

(NEW April 28 PAPILIO SERIES) @17 2006 PROPOSALS FOR A NEW INSECT STUDY, COMMERCE, AND CONSERVATION LAW THAT DEREGULATES DEAD INSECTS, AND PROPOSALS FOR FIXING THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AS APPLIED TO INSECTS By Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes St., Lakewood, Colorado, 80226 (Ph.D. in entomology, University of California, Berkeley) Why Do We Need New Insect Laws? The current laws regulating insects (and plants) in the U.S. are very bad. They were made for deer, and are only incidentally being applied to insects, because no legislators ever thought to make laws specifically targeted at insects that are not agricultural pests. These laws are not serving the conservation of insects well, and the laws are retarding the taxonomic study of insects, and are making criminals out of harmless hobbyist insect collectors. Basically, large animals like deer and Bighorn Sheep can be managed by controlling the numbers hunted using bag limits and exclusion areas etc., and roping and corraling them and transporting them to new sites. Large animals tend to have low population numbers, so might need to be protected from hunting (after all, at the end of the shooting spree in the late 1800s, the U.S. reached a low of population numbers for Bison and deer and nearly every other large animal, and their numbers have gradually recovered since). But insects are tiny by comparison, and their population sizes are huge by comparison. The average insect may be a thousand or a million times more numerous than your average deer'. Insect population sizes cannot be "managed" like deer, because population sizes vary hugely mostly depending on the weather and other uncontrollable factors, and their survival depends on the continued survival of their habitat, rather than useless government intervention. -

Orange Sulphur, Colias Eurytheme, on Boneset

Orange Sulphur, Colias eurytheme, on Boneset, Eupatorium perfoliatum, In OMC flitrh Insect Survey of Waukegan Dunes, Summer 2002 Including Butterflies, Dragonflies & Beetles Prepared for the Waukegan Harbor Citizens' Advisory Group Jean B . Schreiber (Susie), Chair Principal Investigator : John A. Wagner, Ph . D . Associate, Department of Zoology - Insects Field Museum of Natural History 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605 Telephone (708) 485 7358 home (312) 665 7016 museum Email jwdw440(q-), m indsprinq .co m > home wagner@,fmnh .orq> museum Abstract: From May 10, 2002 through September 13, 2002, eight field trips were made to the Harbor at Waukegan, Illinois to survey the beach - dunes and swales for Odonata [dragonfly], Lepidoptera [butterfly] and Coleoptera [beetles] faunas between Midwest Generation Plant on the North and the Outboard Marine Corporation ditch at the South . Eight species of Dragonflies, fourteen species of Butterflies, and eighteen species of beetles are identified . No threatened or endangered species were found in this survey during twenty-four hours of field observations . The area is undoubtedly home to many more species than those listed in this report. Of note, the endangered Karner Blue butterfly, Lycaeides melissa samuelis Nabakov was not seen even though it has been reported from Illinois Beach State Park, Lake County . The larval food plant, Lupinus perennis, for the blue was not observed at Waukegan. The limestone seeps habitat of the endangered Hines Emerald dragonfly, Somatochlora hineana, is not part of the ecology here . One surprise is the. breeding population of Buckeye butterflies, Junonia coenid (Hubner) which may be feeding on Purple Loosestrife . The specimens collected in this study are deposited in the insect collection at the Field Museum . -

Papilio 0 0000 ..;)

1 NEW :ft{t 2 Nov. 15,1982 SERIES • $1.50 PAPILIO 0 0000 ..;) THE Lil'E HISTORY AND l!XlOLOGY f!F AN ALPINE RELICT, BOLORIA !MFR.OBA ACROCNEMA (LEPIDOP.rEltA: NYMPHALIDAE), ILLUSTRATING A NE.W MATHEMATICAL POPULATION CENSUS MEl'HOD Dr. James A. Scott, 60 Estes St., Lakewood, Colorado, 80226 Abstract. The egg, larva, and pupa of B. improba acrocnema are described and illustrated. The larval foodplant Is Salix nivalis. There are five instars; overwintering occurs in the fourth instar, and perhaps also in the first instar. Adults fly slowly near the ground, and are very local. Males patrol to find females. Adults often visit flowers, and bask on dark soil by spreading the wings laterally. A binomial method is derived and used to determine daily population size. Daily population size may be as large as 655, and yearly population size may reach two thousand in a few hectares. Introduction Boloria improba (Butl.) is a circumpolar butterfly, occurring from northern Scandinavia eastward to northern Siberia and arctic America. In North America it occurs from Alaska to Baffin r., south to central Alberta, and a relict subspecies acrocnema G. & s. occurs in the alpine San Juan Mts. of Colorado. The life history and ecology of improba were nearly unknown. This paper presents the complete life history and details of the. life cycle, ecology, and behavior, studied from 1979 to 1981. In addition, a new method of computing the population size of one continuous mark recapture sample is presented, which is useful for quick survey work on colonial animals like insects. -

BULLETIN of the ALLYN MUSEUM 3621 Bayshore Rd

BULLETIN OF THE ALLYN MUSEUM 3621 Bayshore Rd. Sarasota, Florida 33580 Published By The Florida State Museum University of Florida Gainesville. Florida 32611 Number 107 30 December 1986 A REVIEW OF THE SATYRINE GENUS NEOMINOIS, WITH DESCRIPriONS OF THREE NEW SUBSPECIES George T. Austin Nevada State Museum and Historical Society 700 Twin Lakes Drive, Las Vegas, Nevada 89107 In recent years, revisions of several genera of satyrine butterflies have been undertaken (e. g., Miller 1972, 1974, 1976, 19781. To this, I wish to add a revision of the genus Neominois. Neominois Scudder TYPE SPECIES: Satyrus ridingsii W. H. Edwards by original designation (Scudder 1875b, p. 2411 Satyrus W. H. Edwards (1865, p. 2011, Rea.kirt (1866, p. 1451, W. H. Edwards (1872, p. 251, Strecker (1873, p. 291, W. H. Edwards (1874b, p. 261, W. H. Edwards (1874c, p. 5421, Mead (1875, p. 7741, W. H. Edwards (1875, p. 7931, Scudder (1875a, p. 871, Strecker (1878a, p. 1291, Strecker (1878b, p. 1561, Brown (1964, p. 3551 Chionobas W. H. Edwards (1870, p. 1921, W. H. Edwards (1872, p. 271, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, W. H. Edwards (1874b, p. 281, Brown (1964, p. 3571 Hipparchia Kirby (1871, p. 891, W. H. Edwards (1877, p. 351, Kirby (1877, p. 7051, Brooklyn Ent. Soc. (1881, p. 31, W. H. Edwards (1884, p. [7)l, Maynard (1891, p. 1151, Cockerell (1893, p. 3541, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, Hanham (1900, p. 3661 Neominois Scudder (1875b, p. 2411, Strecker (1876, p. 1181, Scudder (1878, p. 2541, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, W. -

2010 Animal Species of Concern

MONTANA NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM Animal Species of Concern Species List Last Updated 08/05/2010 219 Species of Concern 86 Potential Species of Concern All Records (no filtering) A program of the University of Montana and Natural Resource Information Systems, Montana State Library Introduction The Montana Natural Heritage Program (MTNHP) serves as the state's information source for animals, plants, and plant communities with a focus on species and communities that are rare, threatened, and/or have declining trends and as a result are at risk or potentially at risk of extirpation in Montana. This report on Montana Animal Species of Concern is produced jointly by the Montana Natural Heritage Program (MTNHP) and Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (MFWP). Montana Animal Species of Concern are native Montana animals that are considered to be "at risk" due to declining population trends, threats to their habitats, and/or restricted distribution. Also included in this report are Potential Animal Species of Concern -- animals for which current, often limited, information suggests potential vulnerability or for which additional data are needed before an accurate status assessment can be made. Over the last 200 years, 5 species with historic breeding ranges in Montana have been extirpated from the state; Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), Greater Prairie-Chicken (Tympanuchus cupido), Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), Pilose Crayfish (Pacifastacus gambelii), and Rocky Mountain Locust (Melanoplus spretus). Designation as a Montana Animal Species of Concern or Potential Animal Species of Concern is not a statutory or regulatory classification. Instead, these designations provide a basis for resource managers and decision-makers to make proactive decisions regarding species conservation and data collection priorities in order to avoid additional extirpations. -

The Radiation of Satyrini Butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae): A

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011, 161, 64–87. With 8 figures The radiation of Satyrini butterflies (Nymphalidae: Satyrinae): a challenge for phylogenetic methods CARLOS PEÑA1,2*, SÖREN NYLIN1 and NIKLAS WAHLBERG1,3 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Av. Arenales 1256, Apartado 14-0434, Lima-14, Peru 3Laboratory of Genetics, Department of Biology, University of Turku, 20014 Turku, Finland Received 24 February 2009; accepted for publication 1 September 2009 We have inferred the most comprehensive phylogenetic hypothesis to date of butterflies in the tribe Satyrini. In order to obtain a hypothesis of relationships, we used maximum parsimony and model-based methods with 4435 bp of DNA sequences from mitochondrial and nuclear genes for 179 taxa (130 genera and eight out-groups). We estimated dates of origin and diversification for major clades, and performed a biogeographic analysis using a dispersal–vicariance framework, in order to infer a scenario of the biogeographical history of the group. We found long-branch taxa that affected the accuracy of all three methods. Moreover, different methods produced incongruent phylogenies. We found that Satyrini appeared around 42 Mya in either the Neotropical or the Eastern Palaearctic, Oriental, and/or Indo-Australian regions, and underwent a quick radiation between 32 and 24 Mya, during which time most of its component subtribes originated. Several factors might have been important for the diversification of Satyrini: the ability to feed on grasses; early habitat shift into open, non-forest habitats; and geographic bridges, which permitted dispersal over marine barriers, enabling the geographic expansions of ancestors to new environ- ments that provided opportunities for geographic differentiation, and diversification. -

CA Checklist of Butterflies of Tulare County

Checklist of Buerflies of Tulare County hp://www.natureali.org/Tularebuerflychecklist.htm Tulare County Buerfly Checklist Compiled by Ken Davenport & designed by Alison Sheehey Swallowtails (Family Papilionidae) Parnassians (Subfamily Parnassiinae) A series of simple checklists Clodius Parnassian Parnassius clodius for use in the field Sierra Nevada Parnassian Parnassius behrii Kern Amphibian Checklist Kern Bird Checklist Swallowtails (Subfamily Papilioninae) Kern Butterfly Checklist Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor Tulare Butterfly Checklist Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes Kern Dragonfly Checklist Checklist of Exotic Animals Anise Swallowtail Papilio zelicaon (incl. nitra) introduced to Kern County Indra Swallowtail Papilio indra Kern Fish Checklist Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes Kern Mammal Checklist Kern Reptile Checklist Western Tiger Swallowtail Papilio rutulus Checklist of Sensitive Species Two-tailed Swallowtail Papilio multicaudata found in Kern County Pale Swallowtail Papilio eurymedon Whites and Sulphurs (Family Pieridae) Wildflowers Whites (Subfamily Pierinae) Hodgepodge of Insect Pine White Neophasia menapia Photos Nature Ali Wild Wanderings Becker's White Pontia beckerii Spring White Pontia sisymbrii Checkered White Pontia protodice Western White Pontia occidentalis The Butterfly Digest by Cabbage White Pieris rapae Bruce Webb - A digest of butterfly discussion around Large Marble Euchloe ausonides the nation. Frontispiece: 1 of 6 12/26/10 9:26 PM Checklist of Buerflies of Tulare County hp://www.natureali.org/Tularebuerflychecklist.htm -

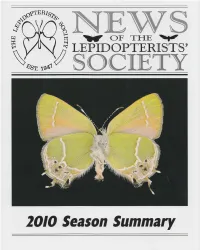

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory ........................................................................................... 3 Alaska ... ........................................ ............................................................... 3 LEPIDOPTERISTS Zone 2: British Columbia .................................................... ........................ ............ 6 Idaho .. ... ....................................... ................................................................ 6 Oregon ........ ... .... ........................ .. .. ............................................................ 10 SOCIETY Volume 53 Supplement Sl Washington ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3: Arizona ............................................................ .................................... ...... 19 The Lepidopterists' Society is a non-profo California ............... ................................................. .............. .. ................... 2 2 educational and scientific organization. The Nevada ..................................................................... ................................ 28 object of the Society, which was formed in Zone 4: Colorado ................................ ... ............... ... ...... ......................................... 2 9 May 1947 and formally constituted in De Montana .................................................................................................... 51 cember -

Samia Cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- Place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates

________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 61, Number 4 Winter 2019 www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________________________________________ Inside: Butterflies of Papua Southern Pearly Eyes in exotic Louisiana venue Philippine butterflies and moths: a new website The Lepidopterists’ Society collecting statement updated Lep Soc, Southern Lep Soc, and Assoc of Trop Lep combined meeting Butterfly vicariance in southeast Asia Samia cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates ... and more! ________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Contents www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________ Digital Collecting -- Butterflies of Papua, Indonesia ____________________________________ Bill Berthet. .......................................................................................... 159 Volume 61, Number 4 Butterfly vicariance in Southeast Asia Winter 2019 John Grehan. ........................................................................................ 168 Metamorphosis. ....................................................................................... 171 The Lepidopterists’ Society is a non-profit ed- Membership Updates. ucational and scientific organization. The ob- Chris Grinter. ....................................................................................... 171 -

Diversification of the Cold-Adapted Butterfly Genus Oeneis Related to Holarctic Biogeography and Climatic Niche Shifts

Published in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 92: 255–265, 2015 which should be cited to refer to this work. Diversification of the cold-adapted butterfly genus Oeneis related to Holarctic biogeography and climatic niche shifts q ⇑ I. Kleckova a,b, , M. Cesanek c, Z. Fric a,b, L. Pellissier d,e,f a Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, 370 05 Cˇeské Budeˇjovice, Czech Republic b Institute of Entomology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Branišovská 31, 370 05 Cˇeské Budeˇjovice, Czech Republic c Bodrocká 30, 821 07 Bratislava, Slovakia d University of Fribourg, Department of Biology, Ecology & Evolution, Chemin du Musée 10, 1700 Fribourg, Switzerland e Landscape Ecology, Institute of Terrestrial Ecosystems, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland f Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, 8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland Both geographical and ecological speciation interact during the evolution of a clade, but the relative contribution of these processes is rarely assessed for cold-dwelling biota. Here, we investigate the role of biogeography and the evolution of ecological traits on the diversification of the Holarctic arcto-alpine butterfly genus Oeneis (Lepidoptera: Satyrinae). We reconstructed the molecular phylogeny of the genus based on one mitochondrial (COI) and three nuclear (GAPDH, RpS5, wingless) genes. We inferred the biogeographical scenario and the ancestral state reconstructions of climatic and habitat requirements. Within the genus, we detected five main species groups corresponding to the taxonomic division and further paraphyletic position of Neominois (syn. n.). Next, we transferred O. aktashi from the hora to the polixenes species group on the bases of molecular relationships. We found that the genus originated in the dry grasslands of the mountains of Central Asia and dispersed over the Beringian Land Bridges to North America several times independently. -

How to Use This Checklist

How To Use This Checklist Swallowtails: Family Papilionidae Special Note: Spring and Summer Azures have recently The information presented in this checklist reflects our __ Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor R; May - Sep. been recognized as separate species. Azure taxonomy has not current understanding of the butterflies found within __ Zebra Swallowtail Eurytides marcellus R; May - Aug. been completely sorted out by the experts. Cleveland Metroparks. (This list includes all species that have __ Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes C; May - Sep. __ Appalachian Azure Celastrina neglecta-major h; mid - late been recorded in Cuyahoga County, and a few additional __ Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes h; rare in Cleveland May; not recorded in Cuy. Co. species that may occur here.) Record you observations and area; July - Aug. Brush-footed Butterflies: Family Nymphalidae contact a naturalist if you find something that may be of __ Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Papilio glaucus C; May - Oct.; __ American Snout Libytheana carinenta R; June - Oct. interest. females occur as yellow or dark morphs __ Variegated Fritillary Euptoieta claudia R; June - Oct. __ Spicebush Swallowtail Papilio troilus C; May - Oct. __ Great Spangled Fritillary Speyeria cybele C; May - Oct. Species are listed taxonomically, with a common name, a Whites and Sulphurs: Family Pieridae __ Aphrodite Fritillary Speyeria aphrodite O; June - Sep. scientific name, a note about its relative abundance and flight __ Checkered White Pontia protodice h; rare in Cleveland area; __ Regal Fritillary Speyeria idalia X; no recent Ohio records; period. Check off species that you identify within Cleveland May - Oct. formerly in Cleveland Metroparks Metroparks. __ West Virginia White Pieris virginiensis O; late Apr.