Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociocultural and Linguistic Contexts of the Russian Sign Language Functioning in Krasnoyarsk Krai

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 2020 13(3): 296-303 DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-0565 УДК 16.21.27 Sociocultural and Linguistic Contexts of the Russian Sign Language Functioning in Krasnoyarsk Krai Liudmila V. Kulikova and Sofya A. Shatokhina Siberian Federal University Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation Received 21.02.2020, received in revised form 25.02.2020, accepted 06.03.2020 Abstract. The article contains an ethnographic description of the conditions governing the use of the regional sign language in Krasnoyarsk Krai within the modern sociolinguistic context. The subject of the discussion is the problem of the linguistic design of sign languages in general, including some features of Russian Sign Language. The study provides statistical information and legal norms for the use of this iconic communication system. A study of the current state of Russian Sign Language functioning in Krasnoyarsk Krai allows us to talk about a change in the status of this sign language, an increasing interest in issues related to its applied significance, and reinforces the need to develop new theoretical approaches to its institutionalization. Keywords: Russian Sign Language, fingerspelling, regional variants, Krasnoyarsk krai, language policy. This research is supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR), Grant No. 20-012-00321 “Regional sign languages: multimodal electronic corpus (the case of the communicative space of Eastern Siberia)”. Research area: linguistics. Citation: Kulikova, L.V., Shatokhina, S.A. (2020). Sociocultural and linguistic contexts of the Russian Sign Language functioning in Krasnoyarsk Krai. J. Sib. Fed. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci., 13(3), 296-303. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-0565. -

Load Article

Arctic and North. 2018. No. 33 55 UDC [332.1+338.1](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.66 The prospects of the Northern and Arctic territories and their development within the Yenisei Siberia megaproject © Nikolay G. SHISHATSKY, Cand. Sci. (Econ.) E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Economy and Industrial Engineering of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Kransnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article considers the main prerequisites and the directions of development of Northern and Arctic areas of the Krasnoyarsk Krai based on creation of reliable local transport and power infrastructure and formation of hi-tech and competitive territorial clusters. We examine both the current (new large min- ing and processing works in the Norilsk industrial region; development of Ust-Eniseysky group of oil and gas fields; gasification of the Krasnoyarsk agglomeration with the resources of bradenhead gas of Evenkia; ren- ovation of housing and public utilities of the Norilsk agglomeration; development of the Arctic and north- ern tourism and others), and earlier considered, but rejected, projects (construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Nizhnyaya Tunguska river; development of the Porozhinsky manganese field; place- ment of the metallurgical enterprises using the Norilsk ores near Lower Angara region; construction of the meridional Yenisei railroad and others) and their impact on the development of the region. It is shown that in new conditions it is expedient to return to consideration of these projects with the use of modern tech- nologies and organizational approaches. It means, above all, formation of the local integrated regional pro- duction systems and networks providing interaction and cooperation of the fuel and raw, processing and innovative sectors. -

Siberian Expectations: an Overview of Regional Forest Policy and Sustainable Forest Management

Siberian Expectations: An Overview of Regional Forest Policy and Sustainable Forest Management July 2003 World Forest Institute Portland, Oregon, USA Authors: V.A. Sokolov, I.M. Danilin, I.V. Semetchkin, S.K. Farber,V.V. Bel'kov,T.A. Burenina, O.P.Vtyurina,A.A. Onuchin, K.I. Raspopin, N.V. Sokolova, and A.S. Shishikin Editors: A. DiSalvo, P.Owston, and S.Wu ABSTRACT Developing effective forest management brings universal challenges to all countries, regardless of political system or economic state. The Russian Federation is an example of how economic, social, and political issues impact development and enactment of forest legislation. The current Forest Code of the Russian Federation (1997) has many problems and does not provide for needed progress in the forestry sector. It is necessary to integrate economic, ecological and social forestry needs, and this is not taken into account in the Forest Code. Additionally, excessive centralization in forest management and the forestry economy occurs. This manuscript discusses the problems facing the forestry sector of Siberia and recommends solutions for some of the major ones. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this book was supported by a grant from the International Research and Exchanges Board with funds provided by the Bureau of Education and Cultural Affairs, a division of the United States Department of State. Neither of these organizations are responsible for the views expressed herein. The authors would particularly like to recognize the very careful and considerate reviews, including many detailed editorial and language suggestions, made by the editors – Angela DiSalvo, Peyton Owston, and Sara Wu. They helped to significantly improve the organization and content of this book. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

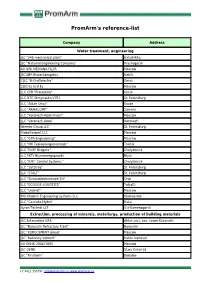

Promarm's Reference-List

PromArm's reference-list Company Address Water treatment, engineering JSC "345 mechanical plant" Balashikha JSC "National Engineering Company" Krasnogorsk AO NPK MEDIANA-FILTR Moscow JSC NPP Biotechprogress Kirishi CJSC "B-Graffelectro" Omsk CJSC Es End Ey Moscow LLC CPB "Protection" Omsk LLC NTC Stroynauka-VITU St. Petersburg LLC "Aidan Stroy" Kazan LLC "ARMACOMP" Samara LLC "Voronezh-Aqua Invest" Moscow LLC "Voronezh-Aqua" Voronezh Hermes Group LLC St. Petersburg Globaltexport LLC Moscow LLC "GPA Engineering" Moscow LLC "MK Teploenergomontazh" Troitsk LLC "NVK" Niagara " Chelyabinsk LLC PKTs Biyskenergoproekt Biysk LLC "RPK" Control Systems " Chelyabinsk LLC "SetStroy" St. Petersburg LLC "STALT" St. Petersburg LLC "Stroisantechservice-1N" Orsk LLC "ECOLINE-LOGISTICS" Tolyatti LLC "Unimet" Moscow PKK Modern Engineering Systems LLC Vladivostok LLC "Cascade-Hydro" Baku Ayron-Technik LLP Ust-Kamenogorsk Extraction, processing of minerals, metallurgy, production of building materials JSC Aldanzoloto GRK Aldan ulus, pos. Lower Kuranakh JSC "Borovichi Refractory Plant" Borovichi JSC "EUROCEMENT group" Moscow JSC "Katavsky cement" Katav-Ivanovsk AO OKHK URALCHEM Moscow JSC OEMK Stary Oskol-15 JSC "Firstborn" Bodaibo +7 8412 350797, [email protected], www.promarm.ru JSC "Aleksandrovsky Mine" Mogochinsky district of Davenda JSC RUSAL Ural Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "SUAL" Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "Khiagda" Bounty district, with. Bagdarin JSC "RUSAL Sayanogorsk" Sayanogorsk CJSC "Karabashmed" Karabash CJSC "Liskinsky gas silicate" Voronezh CJSC "Mansurovsky career management" Istra district, Alekseevka village Mineralintech CJSC Norilsk JSC "Oskolcement" Stary Oskol CJSC RCI Podolsk Refractories Shcherbinka Bonolit OJSC - Construction Solutions Old Kupavna LLC "AGMK" Amursk LLC "Borgazobeton" Boron Volga Cement LLC Nizhny Novgorod LLC "VOLMA-Absalyamovo" Yutazinsky district, with. Absalyamovo LLC "VOLMA-Orenburg" Belyaevsky district, pos. -

Environmental Stress to the Siberian Forests: an Overview

Working Paper Environmental Stress to the Siberian Forests: An Overview Vera Kiseleva WP-96-45 May 1996 International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis • A-2361 Laxenburg • IIASA Telephone: +43 2236 807 • Telefax: +43 2236 71313 • E-Mail: [email protected] Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1 1. General Review of Forest Decline Factors in Siberia.......................................................... 2 1.1. Natural factors..........................................................................................................2 1.2. Anthropogenic factors............................................................................................... 8 1.3. Insufficient reforestation.......................................................................................... 10 1.4. Comparison of the natural respectivelyanthropogenic damages............................... 12 2. Atmospheric Pollution “Climate” in Siberia...................................................................... 12 2.1. Input of different branches of industry.....................................................................12 Relative emission....................................................................................................14 2.2. Cities....................................................................................................................... 15 2.3. Pollutant retention...................................................................................................18 -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 103 2017 International Conference on Culture, Education and Financial Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2017) The Formation of Professional Music Education in the System of Academic Traditions in Yeniseisk Province Evgenya Tsareva Maria Chikhacheva Krasnoyarsk State Institute of Arts Krasnoyarsk State Institute of Arts Krasnoyarsk, Russia Krasnoyarsk, Russia E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The case study presented in the article analyzes Functioning and development of academic traditions in unpublished archive materials and scientific papers to the society requires a complex system of musical investigate the role that music education has played in the communication. Asafiev B.V. pointed out three main formation of regional system of academic traditions in components of its base - the activity of the three main Yeniseisk Province. The authors examine professional music subjects: the composer, performer and listener. [1] However, education establishing in Krasnoyarsk region in the period of an essential link in the "chain" is an educator. Thus, among imperial and Soviet past. Analyzing local materials from social the main elements forming the academic musical culture are: and cultural perspectives gives new results in the study of composer creativity, performance, listener and education, historical events. Along with that, it illuminates the importance which in turn become the whole system for the element base of self-organizational processes in the development of regional of a lower order. culture and fully covers the role of musical and educational institutions in successful development of the academic model in This multicomponent structure, provided that each of the Yeniseisk province in the light of "center-periphery" problem. -

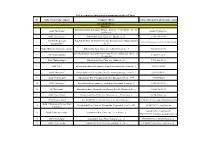

List of Exporters Interested in Supplying Grain to China

List of exporters interested in supplying grain to China № Name of exporting company Company address Contact Infromation (phone num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1st , Vitaly Kozlov str., 25 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. building A 2 OOO ''Zelenyi List'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Butina str., 93 8-914-469-64-44 AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, Komsomolskoe village, Oktober 3 [email protected] Тел.:89243788800 "Komsomolets" str. 30 4 OOO «Bukachachinsky Izvestyank» Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya str., 4 8(3022) 23-21-54 Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky district,. Mankechur village, ul. 5 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 Tsentralnaya 6 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 7 PSK ''Pole'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 8 OOO "Mysovaya" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 9 OOO "Urulyungui" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Dosatuy,Lenin str., 19 B 89245108820 10 OOO "Xin Jiang" Zabaykalsky Krai,Urban-type settlement Priargunsk, Lenin str., 2 8-914-504-53-38 11 PK "Baygulsky" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, Baygul, Shkolnaya str., 6 8(3026) 56-51-35 12 ООО "ForceExport" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 30 building, 7 8-924-388-67-74 13 ООО "Eсospectrum" Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 let Pobedi, 11 8-914-461-28-74 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya -

Russian Federation: Explosion

DREF operation n° MDRRU004 Russian Federation: 24 August 2009 Explosion The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 29,973 (USD 28,127 or EUR 19,762) has been allocated from the International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the National Society in delivering immediate assistance to some 2,100 beneficiaries. Summary: An explosion at the Sayano- Shushenskaya hydropower station in eastern Siberia killed 69 people and left another 6 people missing. One settlement close to the station lost its water supply due to the oil slick in the Yenisei river. The Russian Red Cross will distribute bottled water among the most vulnerable people and provide psychosocial support to the families of power station workers affected by the explosion. Consequences of the blast in the turbine room at Sayano- Shushenskaya hydropower station. Photo: Russian Ministry of Emergencies This operation is expected to be implemented over four months, and will therefore be completed by 22 December 2009; a Final Report will be made available by 22 March 2010. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. <click here for the DREF budget, here for contact details, or here to view the map of the affected area> The situation On 17 August 2009 an explosion at Sayano- Shushenskaya hydropower station in eastern Siberia destroyed the walls and the ceiling of a turbine room which then flooded. -

D.V. Goryaev, I.V. Tikhonova

Hygienic assessment of ambient air quality and health risks to population of Krasnoyarsk region UDC 614.71(470.313) HYGIENIC ASSESSMENT OF AMBIENT AIR QUALITY AND HEALTH RISKS TO POPULATION OF KRASNOYARSK REGION D.V. Goryaev, I.V. Tikhonova Administration of the Federal Supervision Service for Consumer's Rights Protection and Human Welfare in the Krasnoyarsk Region, 21 Karatanova St., Krasnoyarsk, 660049, Russian Federation ____________________________________________________________________________________ This study fulfills the hygienic assessment of ambient air quality in the populated areas of the Krasnoyarsk Region. It is shown that the total number of emission sources in the region is more than 23 600 units, what is higher than in previous years. Around 90.7 % out of them correspond to the set standards of permissible emissions. Air monitoring was carried by the establishments of Roshydromet, Rospotrebnadzor and by other organizations at 94 observation posts in eight urban districts and 2 municipal districts of the region. The status of the ambient air in a sequence of the populated areas of Krasnoyarsk region, namely in the cities Achinsk, Kansk, Krasnoyarsk, Lesosibirsk, Minusinsk, Norilsk, is characterized by the presence of certain pollutants, the level of which exceeds the hygienic standards. Prioritized pollutants are benzo(a)pyrene, suspended solids, nitrogen, and sulfur dioxide, formaldehyde and others. In the settlements the economic entities violate the legal requirements in the field of sanitary and epidemiological welfare of the population. The probability of the population’s health deterioration grows along with the growth of risk factors. The risks of respiratory diseases, immune system, blood and blood-forming organs and the additional mortality are assessed as unacceptable. -

Siberian Platform: Geology and Natural Bitumen

Siberian Platform: Geology and Natural Bitumen Resources By Richard F. Meyer and Philip A. Freeman U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006–1316 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Meyer, R.F., Freeman, P.A., 2006, Siberian platform: Geology and natural bitumen resources: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1316, available online at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2006/1316/. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. CONTENTS Summary 1 Introduction 1 Geology 2 Resources 6 References 11 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Sedimentary basins of the Siberian Platform, Russia 23 TABLES Table 1. Siberian Platform name equivalents 19 Table 2. Bitumen resources of Siberian Platform 20 Table 3. Oil fields of the Siberian Platform 22 i Siberian Platform: Geology and Natural Bitumen Resources Richard F. Meyer and Philip A. Freeman Summary: The Siberian platform is located between the Yenisey River on the west and the Lena River on the south and east. -

Features of Logistics Formation in the Yenisei Province

E3S Web of Conferences 217, 11015 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021711015 ERSME-2020 Features of logistics formation in the Yenisei province Yuliya Lukinykh1,* and Dmitry Kuskashev2 1Krasnoyarsk State Pedagogical University named after V.P.Astafiev, 89 Lebedevoy str., 660049, Krasnoyarsk, Russia 2Krasnoyarsk State Agrarian University, 117 Lenina str., 600000, Krasnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article deals with the features of logistics formation in the Yenisei province in the late XIX – early XX century. The measures aimed at ensuring food supply and basic necessities to the population, restraining the growth of prices, through the implementation of a mechanism for their regulation are considered. The article analyzes transport logistics as a link in the economic system of the Yenisei province, namely: the transport problems of the period under review are listed, the importance of the construction of the Trans-Siberian railway and the development of navigation are emphasized. The conclusion is made about the prerequisites for the economic development of the Yenisei province in the XXth century. 1 Introduction Changes taking place at the present stage in the economic and social life of Russia are directly related to the formation and development of capitalism in Russian society, and this, in turn, causes the need for a deeper understanding of the socio-economic aspect of Russian history. In this regard, the history of Russia in the XIX century occupies a special place, since it was during this period that our country's transition to capitalism took place. For a deep and objective understanding of the country's development, its economic, social, political, and cultural life, more detailed regional historical works are needed.