The Ledger, Winter 2004/2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feed the Birds from Walt Disney’S Mary Poppins

From: “Mary Poppins [Original Soundtrack]” Feed the Birds from Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins by RICHARD M. SHERMAN and ROBERT B. SHERMAN Published Under License From Walt Disney Music Publishing © 1963 Wonderland Music Company, Inc. Copyright Renewed International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Authorized for use by Louis Lagalante NOTICE: Purchasers of this musical file are entitled to use it for their personal enjoyment and musical fulfillment. However, any duplication, adaptation, arranging and/or transmission of this copyrighted music requires the written consent of the copyright owner(s) and of Musicnotes.com. Unauthorized uses are infringements of the copyright laws of the United States and other countries and may subject the user to civil and/or criminal penalties. Musicnotes.com FEED THE BIRDS from Walt Disney’s MARY POPPINS Words and Music by RICHARD M. SHERMAN Slowly, with feeling and ROBERT B. SHERMAN Em Am/E Em B o ooo x x o o ooo x Em Am/E Edim7 Am/E Em o ooo x x o x x x x o o ooo Ear - ly each day to the steps of Saint Paul’s the lit - tle old Am/E Em x x o o ooo bird wom - an comes. In her own spe - cial Am/E Edim7 Am/E Em x x o x x x x o o ooo way to the peo - ple she calls, “Come, buy my © 1963 Wonderland Music Company, Inc. Copyright Renewed International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved Musicnotes.com Authorized for use by: Louis Lagalante 2 B7 Em D7 x o o ooo x x o bags full of crumbs. -

Winning Essays from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland's 2004

Two Thumbs Up! Winning Essays from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s 2004 Essay Contest: Economics Goes to the Movies 6 Ryan McVay/Getty Images The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston is not the tuppence at the bank. At the bank, Jane and Michael are introduced to only Reserve Bank to use entertainment as a the chairman, the senior Mr. Dawes. The children's visit to the bank hook for teaching economics. together takes up less than ten minutes in the movie and yet in those few minutes, the movie introduces the audience to fundamental economic In 2004, the Federal Reserve Bank of concepts. The time value of money and compound interest in financial Cleveland's annual essay contest gave high economics (Hirschey, 727) are introduced in the form of a song sung by school juniors and seniors the opportunity the elder Mr. Dawes, "a giant in the world of finance." Accompanied by a to choose their favorite movie and explain chorus of other bankers, Mr. Dawes tries to convince Michael, with a the economic concepts behind the scenes. We song, the wisdom of saving the tuppence in a bank account and the were so struck by the quality of the essays that magic of compounding as the principal multiplies over time. As Mr. we asked permission to share the first and sec- Dawes explains, Michael Banks's present value of one tuppence can grow ond place winners with our readers. Here they into a future value of a "generous amount" through semiannual com- are. Enjoy! pounding, if Michael deposits the tuppence in the bank. -

Mary Poppins Jr. Full Synopsis from Mtishows.Com

Mary Poppins Jr. Full Synopsis From mtishows.com Bert, a man of many trades, introduces the audience to the unhappy Banks family: father George, mother Winifred, and children Jane and Michael (Prologue). The family; the housekeeper, Mrs. Brill; and the houseboy, Robertson Ay, are shocked when Katie Nanna quits and storms out in frustration. George muses about what he expects from the household - the nanny, in particular ("Cherry Tree Lane - Part 1"). Though Jane and Michael insist upon their own requirements for their caregiver ("The Perfect Nanny"), George dismisses their requests ("Cherry Tree Lane - Part 2"). As if summoned, Mary Poppins appears, offering her services as a nanny. She fits the children's requirements exactly ("Practically Perfect / Practically Perfect - Playoff" ). She then takes the children to the park, where they meet Bert, who describes how wonderful everyday life can be when spending time with Mary ("Jolly Holiday"). At first, the children are not convinced, but when Mary Poppins brings to life a park statue named Neleus, Jane and Michael are in awe of her. The children return home and gush to their father about the nanny, but George is preoccupied ("Winds Do Change"). A few weeks later, the household is preparing for Winifred's party, and Jane and Michael make a mess of the house. Despite Mary's magic ("A Spoonful of Sugar"), the party is ruined when no one attends ("Spoonful - Playoff"). Later, Mary takes the children on a visit to George's workplace, the bank ("Precision and Order - Part 1"). While Clerks are bustling about and clients are trying to convince George to grant them loans, the children burst into the bank ("Precision and Order - Part 2"). -

Cast Members, in Preparation for Our “Mary Poppins Jr.” Auditions We Want to Welcome You and Provide You with Instructions on the Singing Portion of the Audition

Cast Members, In preparation for our “Mary Poppins Jr.” auditions we want to welcome you and provide you with instructions on the singing portion of the audition. Listed below are some selections/snippets we will be using for auditions. These are preferred but you may choose other songs from “Mary Poppins Jr.” not listed. NO OTHER MUSICAL SELECTIONS WILL BE ACCEPTED FOR THIS AUDITION. Please select a song that you are comfortable singing and which best showcases your talents of singing and acting. You will be considered for all roles (male and female) regardless of your song selection, so pick a song you sing well. Remember your breathing techniques and come prepared (don’t forget your water bottle). It is preferred that lyrics be memorized, but you may audition with lyrics if you like. Any questions please direct them to the theatre email at [email protected] Break a leg Ms. Rachel & Ms. Nikki Song Selections “Jolly Holiday” “The Perfect Nanny” “Feed the Birds” “Spoonful full of sugar” “Chim Chim Cher-ee” SONG SELECTIONS “Jolly Holiday” (Bert) Why it's a jolly holiday with Mary Mary makes your heart so light! “The Perfect Nanny” When the day is gray and ordinary (Jane & Michael) Mary makes the sun shine bright! If you want this choice position, Oh, happiness is bloomin' all around her Have a cheery disposition. The daffodils are smilin' at the dove Rosie cheeks, No warts, When Mary holds your hand That's the part I put in. You feel so grand Play games, all sorts Your heart starts beatin' like You must be kind, you must be witty. -

Adultsongbook1 Copy

Book 1 Index – Mixed Selections in Themed Sets All the Things You Are 22 Amazing Grace 13 America the Beautiful 9 Away, Away Come Away With Me (Greensleeves) 5 Beautiful Ohio 8 Blue Moon 3 Feed the Birds (Mary Poppins) 18 Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue 21 For the Beauty of the Earth 2 Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo 24 Hello Dolly 23 How Much Is That Doggie In the Window 20 I’ve Been Workin’ On the Railroad 11 Let There Be Peace on Earth 14 May the Good Lord Bless and Keep You 25 Michael Row the Boat Ashore 15 Moon River 4 My Darlin’ Clementine 10 (The) Old Gray Mare 19 Over the Rainbow 7 Peace in the Valley for Me 16 Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head 6 She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain 12 Side By Side 1 When You Wish Upon a Star 17 Book 1 Mixed Song Selections in Themed Sets Opening: 1 Side by Side Nature: 2 For the Beauty of the Earth 3 Blue Moon 4 Moon River 5 Away, Away, Come Away with Me 6 Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head 7 Over the Rainbow 8 Beautiful Ohio Patriotic: 9 America, the Beautiful Americana: 10 My Darling Clementine 11 I’ve Been Working on the Railroad 12 She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain Inspirational: 13 Amazing Grace 14 Let There Be Peace on Earth 15 Michael, Row the Boat Ashore 16 Peace in the Valley for Me 17 When You Wish Upon a Star Animals: 18 Feed the Birds 19 The Old Gray Mare 20 How Much Is that Doggie in the Window Ladies: 21 Five Foot Two Eyes of Blue 22 All the Things You Are 23 Hello Dolly 24 Hi Lili, Hi-Lo Inspiration (Closing) : 25 May the Good Lord Bless & Keep You "Side By Side" 1 Oh, we ain't got a barrel of money Maybe we're ragged and funny But we'll travel along singing a song Side by side. -

Voice Syllabus / 2012 Edition

74058_MDP_SyllabusCovers_RELEASE2_Layout 1 13-02-06 11:14 AM Page 56 74058_MDP_SyllabusCovers_RELEASE2_LayoutVoice 1 13-02-06 11:14 AM Page 56 VoiceSYLLABUS EDITION SYLLABUS EDITION S35_Voice Syllabus_2016.indd 2 2016-10-17 4:12 PM Contents Message from the President . 5 Register for an Examination Examination Sessions and Registration Deadlines . 106 Getting Started Online Registration . 106 What’s New . 6 Examination Fees . 106 Contact Us . 6 Examination Centers . 106 Examination Scheduling . 106 About Us The Royal Conservatory . 7 Examination Regulations The Royal Conservatory Examinations and Examination Procedures . 107 The Achievement Program . 7 Credits and Refunds for Missed Examinations . 107 The College of Examiners . 7 Candidates with Special Needs . 108 Examinations Offered . 7 Examination Results . 108 Notable Alumni . 8 Tables of Marks . 109 Strengthening Canadian Society Since 1886 . 8 Supplemental Examinations . 110 Musicianship Examinations . 111 Quick Reference— Practical Examination Certifi cates . 111 Examination Requirements Second ARCT Diplomas . 111 School Credits . 111 Certifi cate Program Overview . 9 Medals . 111 Theory Examinations . 10 RESPs . 112 Co-requisites and Prerequisites . 11 Editions . 112 Examination Repertoire . 12 Substitutions . 113 Technical Requirements . 15 Abbreviations . 114 Ear Tests and Sight Singing . 15 Thematic Catalogs . 115 International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) Symbols . 16 Resources Grade-by-Grade Requirements General Resources . 117 Preparatory . 17 General Reference Works . 118 Grade 1 . 18 Voice Resources . 118 Grade 2 . 21 Grade 3 . 24 Grade 4 . 28 Frequently Asked Questions Grade 5 . 32 Practical Examinations . 122 Grade 6 . 37 Theory Co-requisites . 123 Grade 7 . 42 Grade 8 . 49 Practical Examination Day Grade 9 . 58 Checklist for Candidates Grade 10 . 70 Before you Leave Home . -

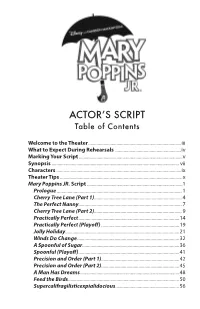

Actor's Script

ACTOR’S SCRIPT Table of Contents Welcome to the Theater ...............................................................................iii What to Expect During Rehearsals ........................................................iv Marking Your Script ........................................................................................v Synopsis ............................................................................................................ vii Characters ..........................................................................................................ix Theater Tips ........................................................................................................x Mary Poppins JR. Script .................................................................................1 Prologue ........................................................................................................1 Cherry Tree Lane (Part 1) .........................................................................4 The Perfect Nanny ......................................................................................7 Cherry Tree Lane (Part 2) .........................................................................9 Practically Perfect ....................................................................................14 Practically Perfect (Playoff) .................................................................19 Jolly Holiday ...............................................................................................21 Winds Do Change -

Study Guide ORIGINAL MUSIC and LYRICS by RICHARD M

©Disney/CML A MUSICAL BASED ON THE STORIES OF P.L. TRAVERS AND THE WALT DISNEY FILM study guide ORIGINAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY RICHARD M. SHERMAN AND ROBERT B. SHERMAN Prepared by Disney Theatrical group Education Department BOOK BY JULIAN FELLOWES NEW SONGS AND ADDITIONAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY GEORGE STILES AND ANTHONY DREWE CO-CREATED BY CAMERON MACKINTOSH intro - welcome Anything can happen if we recognize In Mary Poppins, the factory owner John Northbrook tells Michael that money has a worth (for example, one dollar or, in London, one the magic of everyday life. Author P.L. Travers pound) but it also has a value (or what the money can do to help understood this special kind of magic when she published her first others). Mary Poppins teaches the Banks family (and the audience!) book, Mary Poppins, in 1934. The tale of the mysterious nanny who to value the important things in life: family, friendship and teaches a troubled family to appreciate the important things in life imagination. In Mary Poppins, Mary sings, Anything can happen if went on to become one of the most recognized and beloved stories you let it. Mary Poppins is about discovering the extraordinary world of all time. Thirty years later, Walt Disney released the film based around us, even when things look bleak. This guide is designed to on Travers' stories: a unique mixture of animation and live action help you explore the extraordinary world of Mary Poppins. that has become a classic. Now Mary Poppins flies over audiences and lands on a Disney BROADEN YOUR HORIZON Broadway stage, complete with new songs and breathtaking theatrical magic. -

Mary Poppins Mary Poppins M O V I E C H E C K L I S T M O V I E C H E C K L I S T

Mary Poppins Mary Poppins M O V I E C H E C K L I S T M O V I E C H E C K L I S T Feed the Birds Feed the Birds Lets Go Fly A Kite Lets Go Fly A Kite Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Practically Perfect in Every Way Practically Perfect in Every Way Step in Time Step in Time Spoonful of Sugar Spoonful of Sugar Winds in the east, mist coming in. Winds in the east, mist coming in. Like somethin' is brewin' and bout to begin. Like somethin' is brewin' and bout to begin. Can't put me finger on what lies in store, Can't put me finger on what lies in store, But I fear what's to happen all happened before. But I fear what's to happen all happened before. I Love to laugh I Love to laugh You Wink. You do a double Blink. You Wink. You do a double Blink. You close your eyes and jump! You close your eyes and jump! Chim Chiminy, Chim Chiminy, Chim Chiminy, Chim Chiminy, Chim Chim Chiree Chim Chim Chiree Mary Poppins Mary Poppins M O V I E C H E C K L I S T M O V I E C H E C K L I S T Feed the Birds Feed the Birds Lets Go Fly A Kite Lets Go Fly A Kite Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Practically Perfect in Every Way Practically Perfect in Every Way Step in Time Step in Time Spoonful of Sugar Spoonful of Sugar Winds in the east, mist coming in. -

Mary Poppins Characters and Synopsis.Pdf

Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman Book by Julian Fellowes New Songs and Additional Music and Lyrics by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe Co-Created by Cameron Mackintosh A Musical based on the stories of P.L. Travers and the Walt Disney Film Character List CHARACTERS: DESCRIPTIONS: (ages listed are suggested character age, not actor age) ENSEMBLE MARY POPPINS features a large ensemble of singers and dancers in a variety of supporting roles. MARY POPPINS includes a number of dance styles, including tap, ballet, jazz and other genres. Ensemble roles may not be needed at call-backs. ENSEMBLE ROLES INCLUDE: ANNIE, FANNIE, VALENTINE, TEDDY BEAR, MR. PUNCH, DOLL, TOYS, CHIMNEY SWEEPS, PARKGOERS, MISS SMYTHE, VON HUBBLER, NORTHBROOK, POLICEMAN, BANK EMPLOYEES BERT Bert is a Chimney Sweep and Jack-of-all-Trades. Charming and charismatic. Must move well. Late 20s to mid 30s. Baritone to G. Callback Music: Let’s Go Fly a Kite, Chim-Chiminey & Jolly Holiday MARY POPPINS Jane and Michael’s Nanny, Mary Poppins is a dazzling personality and a force to be reckoned with. Mid 20s. Mezzo Soprano with a strong top. Callback Music: Practically Perfect & Jolly Holiday MR. GEORGE BANKS A bank manager, Mr. Banks is father to Jane and Michael. He tries to be a good provider, but often forgets how to be a good father. Late 30s to Early 40s, Baritone. Callback Music: Precision and Order & Good for Nothing MRS. WINIFRED BANKS A former actress, Mrs. Banks is very busy trying to live up to her husband’s expectations. -

Simply the Harp • Harp Arrangements by Angi Bemiss Sheet Music

Simply the Harp Harp Arrangements by Angi Bemiss Sheet Music All arrangements are within the intermediate level. Each piece of sheet music is printed on cardstock and is provided in two keys – both the keys of C and Eb (front & back). This makes it possible for you to transition seamlessly from one song to the next without having to flip levers or move pedals. Prices vary for sheet music, depending on copyright royalties paid and the number of pages in the publication. All publications are available by visiting our website simplytheharp.com or emailing [email protected] or by phoning us at (404)357-9543. They are also available online from Melody’s Traditional Music (folkharp.com), Atlanta Harp Center (atlantaharpcenter.com), Kolacny Music (kolacnymusic.com) and from other harp music stores. 10,000 Reasons (Bless the Lord) Emmaus Medley A Thousand Years Alleluia; Servant Song; Surely the Presence Alleluia Have You Seen Jesus My Lord?; Open Our Eyes Amazing Grace Essence of “The Swan” And So It Goes Evening Prayers Medley Artemisia You Are My Hiding Place All Through The Night As the Deer Sweet Be Your Sleep Be Thou My Vision Far Away Beautiful Dreamer Feed the Birds (from the movie “Mary Poppins”) Blessings Forever In Love Brahms' Lullaby Forrest Gump – The Feather Theme Breath of Heaven/"Mary's Song" (The) Friendship Theme (from the movie "Beaches") Can You Feel The Love Tonight (from “The Lion King”) Gabriel’s Oboe Carol Ann Give Thanks Cavalleria Rusticana/Ave Maria Glory Medley Charlotte’s Web Medley – Lullaby & Ordinary -

Mary Poppins *****

***** MARY POPPINS ***** CAST Mary Poppins Bert Mr. George Banks Mrs. Winifred Banks Jane Banks Michael Banks Ellen: Maid Mrs. Brill: Cook Katie Nanna, Nannies Constable Jones Admiral Boom & Mates Uncle Arthur The Bird Woman Mr. Dawes, Sr. & Bankers: Mr. Dawes, Jr.; Mr. Grubbs; Mr. Tomes Penguin Waiters & Animals (15-20); Supercal band (6): 1 scene Chimneysweeps (20-25): 1 scene London Choir (20-30): on floor and 1 number on stage Lullaby Chorus: 6-8 Girls: Stay Awake; Feed the Birds SCENES SCENE 1: 17 Cherry Tree Lane: Sister, The Life I Lead, Advertisement ................. 2 SCENE 2: Next Morning: 17 Cherry Tree Lane: The Interview .............................. 11 SCENE 3: Nursery: Spoonful ................................................................................... 14 SCENE 4: In the Park ............................................................................................... 17 SCENE 5: Jolly Holiday: Supercal ........................................................................... 19 SCENE 6: Nursery: Stay Awake .............................................................................. 23 SCENE 7: Next Morning: Out of Sorts .................................................................... 25 SCENE 8: Uncle Arthur ............................................................................................ 27 SCENE 9: Parlor: A British Bank ............................................................................. 30 SCENE 10: Nursery: Feed the Birds .......................................................................