Report Archaeological Sensitivity Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AQUIFERPROTECTIONAREA SW Estport , CONNECTICUT

n M ! R F S o N G o Godfrey Pond C e t Inwood Rd u P u n o d a r u d B W d r n n r t e R L r e t d R d b e r t e R o t t s n R 111 D i l n I o a e l a r o M o t e n l s S1 r R i t t V W w l r A O d n k a l d e K i i R e i S d 1 n M a n n l R W B e l y D H o id g e a a T u a l R t R i Wheelers Pond 1 H L l a a r x d n l B o a g e R d r r a v a d o F d d e d d R n r T t e Nod Hill Pond t e y n l n e R r e R R W d h d o e u d r D e D d i y n u D R v M R e e E w e e d n k d e o S H R u b n d w r r a r r r e Chestnut Hill r c d e o e d d w 7 R H u w o n b L e r D d l R d Mill River h B o d L w t S W n d b n s s s u Plymouth Avenue Pond £ a d s y e ¤ r A u o i R R s o n i b Pipers t o R h d Hill R n d o i n L c S d d e 5 C t a e d r r d d B o U H g Powells Hill k t t o r t 9 d e S k n Spruc u p r l d D o R d c r R R L P e S i a r n s l H r Cristina R 136 i h L Ln e n B l i r T R o d n r d s l L S o n r R V e o H o k L R i r M d t M Killian A H G L a S ve d R e s R y n l g e d Pin 1 i l C r a d w r n M e d d e r a a 1 i R r d c y e D h k h s r S R 1 d o d c E Cricker Brook i t c a k n l 7 r M d r u w a e l o R l n y g a R d r S n d l Dr c e B W od l e F nwo d r Nature Pond o t utt o l S i B t w d C h l S B n y i d r o t l e W ch R e i D R e e o o D p B r M Hill Rd i L d n r H R ey l on r il H P H n L H o ls illa w o d v r w t w a w on La n o s D D d d e O e S e n w r g r R e p i e i W k l n n e d d W t r g L e v e r t l y e l D l r y g l 53 e e T a e o R e l s d y d H n Plum rkw o a D i P a R n l r a S d R L V W i w o u r u Jennings Brook l -

Transit Oriented Development Final Report | September 2010

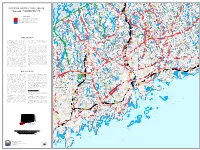

FTA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS DRAFT/FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DANBURY BRANCH IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2010 In Cooperation with U.S. Department CONNECTICUT South Western Regional Planning Agency of Transportation DEPARTMENT OF Federal Transit TRANSPORTATION Administration FTA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS DRAFT/FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DANBURY BRANCH IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2010 In Cooperation with U.S. Department CONNECTICUT South Western Regional Planning Agency of Transportation DEPARTMENT OF Federal Transit TRANSPORTATION Administration Abstract This report presents an evaluation of transit-oriented development (TOD) opportunities within the Danbury Branch study corridor as a component of the Federal Transit Administration Alternatives Analysis/ Draft Environmental Impact Statement (FTA AA/DEIS) prepared for the Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT). This report is intended as a tool for municipalities to use as they move forward with their TOD efforts. The report identifies the range of TOD opportunities at station areas within the corridor that could result from improvements to the Danbury Branch. By also providing information regarding FTA guidelines and TOD best practices, this report serves as a reference and a guide for future TOD efforts in the Danbury Branch study corridor. Specifically, this report presents a definition of TOD and the elements of TOD that are relevant to the Danbury Branch. It also presents a summary of FTA Guidance regarding TOD and includes case studies of FTA-funded projects that have been rated with respect to their livability, land use, and economic development components. Additionally, the report examines commuter rail projects both in and out of Connecticut that are considered to have applications that may be relevant to the Danbury Branch. -

Green's Farms URBITRANR EPORT

Individual Station Report Green's Farms URBITRANR EPORT CONTENTS: Stakeholder Interview Customer Opinion Survey Parking Inventory & Utilization Station Condition Inspection Lease Narrative and Synopsis Station Operations Review Station Financial Review URBITRAN Prepared to Connecticut Department of Transportation S ubmitted by Urbitran Associates, Inc. July 2003 June 2003 June 2003 June 2003 June 2003 June 2003 June 2003 Stakeholder Interview URBITRANR EPORT URBITRAN Prepared to Connecticut Department of Transportation S ubmitted by Urbitran Associates, Inc. Westport According to those at the meeting, which included the First and Second Selectmen and a representative from the Police Department, who run the station, Harry Harris wants CDOT to take control of the stations and parking. This was the first issue brought up by the town representatives – that the State wants to run the stations to provide better quality control, and that the State feels that this is the only solution to improve the supply of parking along the entire line. Furthermore, the feeling was that CDOT would be exempt from local zoning and would therefore be in a position to deck parking lots without local permission. Westport feels that they do a good job with the two town stations, and that they have an excellent relationship with Carl Rosa regarding maintenance and operations and with Harry Harris regarding policy. They feel strongly that if other towns ran their stations and parking like they do CDOT would have far fewer issues to contend with. Westport understands the desire for uniformity among the stations and supports that policy, albeit with concern regarding home rule issues. Westport, ultimately, is satisfied with the status quo, and feels the working relationship is excellent, the division of responsibilities clear, and their ability to have input into the ADA design process excellent. -

Norwalk Community Food Report

Norwalk Community Food Report January 2020 Prepared and Presented by: Fairfield University’s Center for Social Impact Norwalk Health Department Additional Data Analysis provided by: CT Food Bank Research Team: Director of Center for Social Impact: Melissa Quan Research Coordinator: Jonathan Delgado Student Researcher: Mahammad Camara ‘19 Editors: Sophia Gourgiotis Luckario Alcide Eileen Michaud Research Partners: Norwalk Health Department Health Educator: Theresa Argondezzi Food Access Project Coordinator: Pamela Flausino Melo da Silva Additional Data Resources Made Available by CT Food Bank: Jamie Foster, PhD Acknowledgments Center for Social Impact 4 Healthy for Life Project 5 Project Overview 6 How To Use This Report 7 Norwalk Food Agencies 8 Norwalk Maps And Tables Food Insecurity 9 Populations Children 12 Immigrant (Foreign Born) Population 14 Seniors 16 Single Parent/Guardian 18 Services Disability 20 Free & Reduced-Price Lunch 22 SNAP & WIC 24 Social Determinants Educational Attainment 28 Housing Burden 32 Transportation 34 Unemployment 36 Key Findings 38 Taking Action: Norwalk Food Access Initiative 39 Appendix A: Census Boundary Reference Map 41 Appendix B: Population Density Table 42 Appendix C: SNAP & WIC Retailers 43 Appendix D: SNAP & WIC Information 45 Appendix E: Data Source Tables 46 Glossary 47 References 48 TABLE OF Contents Page 3 of 50 Center for Social Impact The Center for Social Impact was founded in 2006 with the goal of integrating the Jesuit, Catholic mission of Fairfield University, which includes a commitment to service and social justice, through the academic work of teaching and research. The Center for Social Impact has three major programs: 1. Community-Engaged Learning (formerly known as Service Learning) 2. -

A Q U I F E R P R O T E C T I O N a R E a S N O R W a L K , C O N N E C T I C

!n !n S c Skunk Pond Beaver Brook Davidge Brook e d d k h P O H R R O F p S o i d t n n l c t u i l R a T S d o i ll l t e e lv i d o t R r r d r l h t l l a H r n l t r M b a s b R d H e G L R o r re R B C o o u l e t p o n D o e f L i s Weston Intermediate School y l o s L d r t e Huckleberry Hills Brook e t d W d r e g Upper Stony Brook Pond N L D g i b R o s n Ridgefield Pond a t v d id e g e H r i l Country Club Pond b e a R d r r S n n d a g e L o n tin a d ! R d l H B n t x H e W Still Pond d t n Comstock Knoll u d a R S o C R k R e L H d i p d S n a l l F tt h Town Pond d l T te r D o e t l e s a t u e L e c P n n b a n l R g n i L t m fo D b k H r it to Lower Stony Brook Pond o r A d t P n d s H t F u d g L d d i Harrisons Brook R h e k t R r a e R m D l S S e e G E o n y r f ll H rt R r b i i o e n s l t ld d d o r l ib l a e r R d L r O e H w i Fanton Hill g r l Cider Mill School P y R n a ll F i e s w L R y 136 e a B i M e C H k A s t n d o i S d V l n 3 c k r l t g n n a d R i u g d o r a L 3 ! a l r u p d R d e c L S o s e Hurlbutt Elementary School R d n n d D A i K w T n d o O n D t f R l g d R l t ad L i r e R e e r n d L a S i m a o f g n n n D d n R o t h n Middlebrook School ! l n t w Lo t a 33 i n l n i r E id d D w l i o o W l r N e S a d l e P g n V n a h L C r L o N a r N a S e n e t l e b n l e C s h f ! d L nd g o a F i i M e l k rie r id F C a F r w n P t e r C ld l O e r a l y v f e u e o O n e o a P i O i s R w e t n a e l a n T t b s l d l N l k n t g i d u o e a o R W R Hasen Pond n r r n M W B y t Strong -

South Norwalk Individual Station Report

SOUTH NORWALK TRAIN STATION VISUAL INSPECTION REPORT January 2007 Prepared by the Bureau of Public Transportation Connecticut Department of Transportation South Norwalk Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Overview: The South Norwalk Train Station is located in the SoNo District section of the City of Norwalk. The city and the Department reconstructed the South Norwalk Train Station about 15 years ago. A parking garage, waiting room, ticket windows, municipal electricity offices, and security office replaced the old westbound station building. The old eastbound station building was rehabilitated at the same time. The interior has been nicely restored. Motorists can get to the station from nearby I-95, Route 7 and Route 1. However, one must be familiar with the since trailblazing is inconsistent. Where signs indicate the station, the message is sometimes lost amidst the clutter of street, advertising, landmark and business signs. A bright, clean tunnel connects the two station buildings. Elevators and ramps provide platform accessibility for the less able. The two ten-car platforms serve as center island platforms at their respective east ends for Danbury Branch service. At this time, the Department is replacing the railroad bridge over Monroe Street as part of its catenary replacement project. Bridge plates are in place over Track 3 to accommodate the required track outage. The South Norwalk Station is clean except around the two pocket tracks at the east end of the station. Track level litter has piled up along the rails and under the platforms. Litter is also excessive along the out of service track. Maintenance Responsibilities: Owner: City Operator: City Platform Lights: Metro-North Trash: Metro-North Snow Removal: Metro-North Shelter Glazing: Metro-North Platform Canopy: Metro-North Platform Structure: Metro-North Parking: LAZ Page 2 South Norwalk Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Station Layout: Aerial Photo by Aero-Metric, Inc. -

Historic Resources Evaluation Report

Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. Historic Resources Evaluation Report Walk Bridge Replacement Project Norwalk, Connecticut State Project No. 0301-0176 Prepared for HNTB Corporation Boston, Massachusetts by Archaeological and Historical Services, Inc. Storrs, Connecticut for submission to The Connecticut Department of Transportation Authors: Bruce Clouette Marguerite Carnell Rodney Stacey Vairo August 2016 ABSTRACT AND MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The State of Connecticut, through the Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT), is planning the replacement of the 1896 Norwalk River railroad swing bridge in Norwalk, Connecticut, in order to improve the safety and reliability of service along the state’s busiest rail corridor. The project will receive funding from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), requiring consultation with the State Historic Preservation Office (CTSHPO) regarding possible impacts to significant historic and archaeological resources under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act. CTDOT is studying variants of the movable replacement bridge, including a vertical lift span option and a bascule span option. This report presents the results of research, field inspection, and analysis for the historic resources that may be affected by the project. Historic resources as considered herein are limited to above-ground (i.e., standing) properties: buildings, structures, objects, districts, landscapes, and sites that meet the criteria for listing in -

East Norwalk Historical Walks

EAST NORWALK HISTORICAL WALKS Whenever you are in East Norwalk or the Calf Pasture Beach area you are surrounded by locations important in Norwalk history. For thousands of years the native American Indians lived here. They built their dwellings along the shoreline. Since their dwellings were surrounded by a stockade for defense against warlike tribes, early Europeans called the Indians' living area a Fort. They lived on the bounties of the sea, the local environment which teamed with wildlife and also planted corn. In 1614, Adriaen Block, a navigator from the Netherlands, whose ship the Restless was sailing along the Connecticut Coast trading with the Indians, recorded his visit to what he called "The Archipelago". His written record was the first mention of what we know as the Norwalk Islands. The Pequot Wars (1637-1638) brought Colonial Soldiers close to this area and the final battle of the war was fought in what is called the Sasqua swamp, an area now part of Fairfield, CT at the Southport line. Two of the leaders of these soldiers, Roger Ludlow and Daniel Partrick were impressed by the potential of the area and independently purchased land from the Indians in 1640/1641. Ludlow bought the land between the Saugatuck River and the middle of the Norwalk River (approximately 15,777 acres) and Partrick bought the land from the middle of the Norwalk River east to the Five-Mile River. Neither one, so far as we know, ever lived on the land that they purchased. A monument to Roger Ludlow is within the traffic circle at the junction of Calf Pasture Beach Road and Gregory Boulevard. -

CT2030 2020-2030 Base SOGR Investment $10.341 $0.023 $5.786

Public Transportation Total Roadway Bus Rail ($B) ($B) ($B) CT2030 2020-2030 Base SOGR Investment $10.341 $0.023 $5.786 $16.149 2020-2030 Enhancement Investment $3.867 $0.249 $1.721 $5.837 Total $14.208 $0.272 $7.506 $21.986 Less Allowance for Efficiencies $0.300 CT2030 Program total $21.686 Notes: 2020-2030 Base SOGR Investment Dollars for Roadway also includes funding for bridge inspection, highway operations center, load ratings 2020-2030 program includes "mixed" projects that have both SOGR and Enhancement components. PROJECT ROUTE TOWN DESCRIPTION PROJECT COST PROJECT TYPE SOGR $ 0014-0185 I-95 BRANFORD NHS - Replace Br 00196 o/ US 1 18,186,775 SOGR 100% $ 18,186,775 0014-0186 CT 146 BRANFORD Seawall Replacement 7,200,000 SOGR 100% $ 7,200,000 0015-0339 CT 130 BRIDGEPORT Rehab Br 02475 o/ Pequonnock River (Phase 2) 20,000,000 SOGR 100% $ 20,000,000 0015-0381 CT 8 BRIDGEPORT Replace Highway Signs & Supports 10,000,000 SOGR 100% $ 10,000,000 0036-0203 CT 8 Derby-Seymour Resurfacing, Bridge Rehab & Safety Improvements 85,200,000 SOGR 100% $ 85,200,000 0172-0477 Various DISTRICT 2 Horizontal Curve Signs & Pavement. Markings 6,225,000 SOGR 100% $ 6,225,000 0172-0473 CT 9 & 17 DISTRICT 2 Replace Highway Signs & Sign Supports 11,500,000 SOGR 100% $ 11,500,000 0172-0490 Various DISTRICT 2 Replace Highway Signs & Supports 15,500,000 SOGR 100% $ 15,500,000 0172-0450 Various DISTRICT 2 Signal Replacements for APS Upgrade 5,522,170 SOGR 100% $ 5,522,170 0173-0496 I-95/U.S. -

Darien, Connecticut 2006 Town Plan of Conservation & Development

DARIEN, CONNECTICUT 2006 TOWN PLAN OF CONSERVATION & DEVELOPMENT Effective June 25, 2006 Darien Town Plan of Conservation & Development Adopted: May 23, 2006 Effective: June 25, 2006 Planning & Zoning Commission Members: Patrick J. Damanti, Chairman Frederick B. Conze, Vice-Chairman Joseph H. Spain, Secretary Peter Bigelow Ursula W. Forman David J. Kenny Traffic and Transportation Consultant: URS Corporation Environmental Resources Consultant: Fitzgerald & Halliday, Inc. Graphics work in Chapter 9: Wesley Stout Associates PLANNING & ZONING COMMISSION’S STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Section 8-23 of the Connecticut General Statutes requires that local planning commissions prepare a Plan of Conservation and Development (“Plan” or “Town Plan”) at least once every ten years. The Town of Darien has been creating and implementing such plans for over 40 years. The Town Plan is just that - a plan/a vision/a roadmap. The Town Plan offers various projects and directions, many of which can be implemented on a variety of levels and scopes. The Plan has specifically been developed without a cost/benefit analysis and without a priority list of projects. The development of the costs, affordability, priorities, and other issues are left to the involved private sector parties and the appropriate town boards at the time that the projects are recommended for implementation. The fundamental goal has been, and continues to be, the preservation and enhancement of an attractive suburban living environment, but within those broad parameters are numerous factors which must be addressed to best assure achieving that goal. This Plan is the Town's most recent attempt to guide private and public participants toward this goal. -

Customer Opinion Survey Final Report

Task 1.2: Customer Opinion Survey Final Report URBITRANR EPORT URBITRAN Prepared to Connecticut Department of Transportation S ubmitted by Urbitran Associates, Inc. May 2003 Task 1.2:Technical Memorandum Customer Opinion Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF FINDINGS ............................................................................................1 BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................................1 METHODOLOGY.........................................................................................................................................................1 FINDINGS ..................................................................................................................................................................1 EXHIBIT 1: SURVEY SAMPLE.....................................................................................................................................2 COMPARISON TO METRO-NORTH RAILROAD CUSTOMER OPINION SURVEY ...........................................................10 CHAPTER ONE: GENERAL PROFILE OF SURVEY RESPONDENTS.........................................................12 SYSTEM-WIDE ANALYSIS OF SURVEY QUESTIONS 1, 2, AND 3 .................................................................................13 SYSTEM-WIDE ANALYSIS OF SURVEY QUESTIONS 4, 5, 6, AND 7 .............................................................................15 SYSTEM-WIDE ANALYSIS OF SURVEY -

Little Red Schoolhouse Guidebook Glossary

Norwalk Historical Society The Little Red Schoolhouse Program Pre-Visit Guidebook Dear Visitor Before you, your class, your troop, or your family visit Mill Hill Historic Park and take part in the Little Red Schoolhouse Program, read through this resource book and complete some of the Pre-Visit activities to give you a better understanding of the history of Norwalk during the Colonial & Revolutionary War period. The words in bold are defined at the end in the glossary section. To continue your historical learning off site, there are also Post-Visit activities included. Have fun stepping back into the past! NORWALK HISTORICAL SOCIETY Mailing Address: P.O. Box 1640 Norwalk, CT 06852 Mill Hill Historic Park Address: 2 East Wall Street Norwalk, CT 06851 203-846-0525 [email protected] www.norwalkhistoricalsociety.org Index 4 The Native Americans’ Way of Life ~ 1500s 6 Europeans Arrive in America ~ 1600s 7 The Purchase of Norwalk ~ 1640 10 Norwalk Becomes a Town ~ 1640 – 1651 The Colonial Era ~ 1651 – 1775 12 Governor Thomas Fitch IV ~ The Colonial Governor from Norwalk 14 Governor Fitch’s Law Office and a Look at Life in the Colonial Days ~ 1740s The Revolutionary Era 17 The Road to Revolution ~ 1763 – 1775 17 The Revolutionary War ~ 1775 – 1783 18 The Battle and Burning of Norwalk ~ 1779 20 Norwalk Rebuilds & The Firelands ~ 1779 - 1809 21 The Little Red Schoolhouse (The Down Town District School) ~ 1826 23 Book a Tour 24 Glossary 26 Reading Questions Answer Key 28 Image Credits 30 Bibliography 31 Norwalk Historical Society Contact Info 32 Guidebook Credits The Native Americans’ Way of Life - 1500s Native Americans were the first people to live in Connecticut and had been living in the Norwalk area for thousands of years.