Historic Resources Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M7 Electric Multiple Unitанаnew York

Electric Multiple Unit -M- 7 POWERCAR WITH TOILET ---10' 6' B END FEND I 3,200 mi , -: -" 0 C==- ~=0 :- CJCJ ~~[] CJCJCJCJCJCJ [] I D b 01 " ~) -1::1 1211-1/2 t~J ~~W ~~IL...I ~w -A'-'1~~~- I ~~ 309~mmt ~ 1 I~ 11 m 2205~16~m-! 591..1.6" mm --I I 1- -- 59°6" ° 4°8-1/2. , ~ 16,~:,60~m ~-- -;cl 10435mm ~ .-1 25.908 mm F END GENERAL DATA wheelchair locations 2 type of vehicle electric multiple unit passenger per car (seated) under design operator Metropolitan Transportation Authority passengers per car (standing) crush load under design Long Island Railroad order date May 1999 TECHNICAL CHARACTERISTICS quantity 113 power cars without toilet .power fed by third rail: 400-900 Vdc 113 power cars with toilet .auxiliary voltages: 230 Vac / 3 ph / 60 Hz train consist up to 14 cars 72 Vdc .AC traction motor: 265 hp (200 kW) DIMENSIONS AND WEIGHf Metric Imperial .dynamic and pneumatic (tread & disc) braking system length over coupler 25,908 mm 85'0" .coil spring primary suspension width over side sheets 3,200 mm 10'6" .air-bag secondary suspension rail to roof height 3,950 mm 12' II Y;" .stainless steel carbody rail to top of floor height I ,295 mm 51" .fabricated steel frame trucks rail to top of height 4,039 mm 13' 3" .automatic parking brake doorway width 1,270 mm 50" .forced-air ventilation doorway height 1,981 mm 6'6" .air-conditioning capacity of 18 tons floor to high ceiling height 2,261 mm 89" .electric strip heaters floor to low ceiling height 2,007 mm 79" .ADA compliant toilet room (8 car) wheel diameter 914 mm 36" .vacuum sewage system -

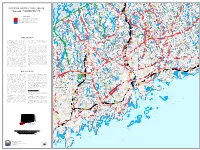

AQUIFERPROTECTIONAREA SW Estport , CONNECTICUT

n M ! R F S o N G o Godfrey Pond C e t Inwood Rd u P u n o d a r u d B W d r n n r t e R L r e t d R d b e r t e R o t t s n R 111 D i l n I o a e l a r o M o t e n l s S1 r R i t t V W w l r A O d n k a l d e K i i R e i S d 1 n M a n n l R W B e l y D H o id g e a a T u a l R t R i Wheelers Pond 1 H L l a a r x d n l B o a g e R d r r a v a d o F d d e d d R n r T t e Nod Hill Pond t e y n l n e R r e R R W d h d o e u d r D e D d i y n u D R v M R e e E w e e d n k d e o S H R u b n d w r r a r r r e Chestnut Hill r c d e o e d d w 7 R H u w o n b L e r D d l R d Mill River h B o d L w t S W n d b n s s s u Plymouth Avenue Pond £ a d s y e ¤ r A u o i R R s o n i b Pipers t o R h d Hill R n d o i n L c S d d e 5 C t a e d r r d d B o U H g Powells Hill k t t o r t 9 d e S k n Spruc u p r l d D o R d c r R R L P e S i a r n s l H r Cristina R 136 i h L Ln e n B l i r T R o d n r d s l L S o n r R V e o H o k L R i r M d t M Killian A H G L a S ve d R e s R y n l g e d Pin 1 i l C r a d w r n M e d d e r a a 1 i R r d c y e D h k h s r S R 1 d o d c E Cricker Brook i t c a k n l 7 r M d r u w a e l o R l n y g a R d r S n d l Dr c e B W od l e F nwo d r Nature Pond o t utt o l S i B t w d C h l S B n y i d r o t l e W ch R e i D R e e o o D p B r M Hill Rd i L d n r H R ey l on r il H P H n L H o ls illa w o d v r w t w a w on La n o s D D d d e O e S e n w r g r R e p i e i W k l n n e d d W t r g L e v e r t l y e l D l r y g l 53 e e T a e o R e l s d y d H n Plum rkw o a D i P a R n l r a S d R L V W i w o u r u Jennings Brook l -

Transit Oriented Development Final Report | September 2010

FTA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS DRAFT/FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DANBURY BRANCH IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2010 In Cooperation with U.S. Department CONNECTICUT South Western Regional Planning Agency of Transportation DEPARTMENT OF Federal Transit TRANSPORTATION Administration FTA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS DRAFT/FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DANBURY BRANCH IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2010 In Cooperation with U.S. Department CONNECTICUT South Western Regional Planning Agency of Transportation DEPARTMENT OF Federal Transit TRANSPORTATION Administration Abstract This report presents an evaluation of transit-oriented development (TOD) opportunities within the Danbury Branch study corridor as a component of the Federal Transit Administration Alternatives Analysis/ Draft Environmental Impact Statement (FTA AA/DEIS) prepared for the Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT). This report is intended as a tool for municipalities to use as they move forward with their TOD efforts. The report identifies the range of TOD opportunities at station areas within the corridor that could result from improvements to the Danbury Branch. By also providing information regarding FTA guidelines and TOD best practices, this report serves as a reference and a guide for future TOD efforts in the Danbury Branch study corridor. Specifically, this report presents a definition of TOD and the elements of TOD that are relevant to the Danbury Branch. It also presents a summary of FTA Guidance regarding TOD and includes case studies of FTA-funded projects that have been rated with respect to their livability, land use, and economic development components. Additionally, the report examines commuter rail projects both in and out of Connecticut that are considered to have applications that may be relevant to the Danbury Branch. -

A Q U I F E R P R O T E C T I O N a R E a S N O R W a L K , C O N N E C T I C

!n !n S c Skunk Pond Beaver Brook Davidge Brook e d d k h P O H R R O F p S o i d t n n l c t u i l R a T S d o i ll l t e e lv i d o t R r r d r l h t l l a H r n l t r M b a s b R d H e G L R o r re R B C o o u l e t p o n D o e f L i s Weston Intermediate School y l o s L d r t e Huckleberry Hills Brook e t d W d r e g Upper Stony Brook Pond N L D g i b R o s n Ridgefield Pond a t v d id e g e H r i l Country Club Pond b e a R d r r S n n d a g e L o n tin a d ! R d l H B n t x H e W Still Pond d t n Comstock Knoll u d a R S o C R k R e L H d i p d S n a l l F tt h Town Pond d l T te r D o e t l e s a t u e L e c P n n b a n l R g n i L t m fo D b k H r it to Lower Stony Brook Pond o r A d t P n d s H t F u d g L d d i Harrisons Brook R h e k t R r a e R m D l S S e e G E o n y r f ll H rt R r b i i o e n s l t ld d d o r l ib l a e r R d L r O e H w i Fanton Hill g r l Cider Mill School P y R n a ll F i e s w L R y 136 e a B i M e C H k A s t n d o i S d V l n 3 c k r l t g n n a d R i u g d o r a L 3 ! a l r u p d R d e c L S o s e Hurlbutt Elementary School R d n n d D A i K w T n d o O n D t f R l g d R l t ad L i r e R e e r n d L a S i m a o f g n n n D d n R o t h n Middlebrook School ! l n t w Lo t a 33 i n l n i r E id d D w l i o o W l r N e S a d l e P g n V n a h L C r L o N a r N a S e n e t l e b n l e C s h f ! d L nd g o a F i i M e l k rie r id F C a F r w n P t e r C ld l O e r a l y v f e u e o O n e o a P i O i s R w e t n a e l a n T t b s l d l N l k n t g i d u o e a o R W R Hasen Pond n r r n M W B y t Strong -

South Norwalk Individual Station Report

SOUTH NORWALK TRAIN STATION VISUAL INSPECTION REPORT January 2007 Prepared by the Bureau of Public Transportation Connecticut Department of Transportation South Norwalk Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Overview: The South Norwalk Train Station is located in the SoNo District section of the City of Norwalk. The city and the Department reconstructed the South Norwalk Train Station about 15 years ago. A parking garage, waiting room, ticket windows, municipal electricity offices, and security office replaced the old westbound station building. The old eastbound station building was rehabilitated at the same time. The interior has been nicely restored. Motorists can get to the station from nearby I-95, Route 7 and Route 1. However, one must be familiar with the since trailblazing is inconsistent. Where signs indicate the station, the message is sometimes lost amidst the clutter of street, advertising, landmark and business signs. A bright, clean tunnel connects the two station buildings. Elevators and ramps provide platform accessibility for the less able. The two ten-car platforms serve as center island platforms at their respective east ends for Danbury Branch service. At this time, the Department is replacing the railroad bridge over Monroe Street as part of its catenary replacement project. Bridge plates are in place over Track 3 to accommodate the required track outage. The South Norwalk Station is clean except around the two pocket tracks at the east end of the station. Track level litter has piled up along the rails and under the platforms. Litter is also excessive along the out of service track. Maintenance Responsibilities: Owner: City Operator: City Platform Lights: Metro-North Trash: Metro-North Snow Removal: Metro-North Shelter Glazing: Metro-North Platform Canopy: Metro-North Platform Structure: Metro-North Parking: LAZ Page 2 South Norwalk Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Station Layout: Aerial Photo by Aero-Metric, Inc. -

Meeting of the Metro-North Railroad Committee

• Metropolitan Transportation Authority ~ Meeting of the Metro-NorthI Railroad Committee May 2014 Members J. Sedore, Chair F. Ferrer, MTA Vice Chairman J. Balian R. Bickford J. Blair N. Brown J. Kay S. Metzger C. Moerdler J. Molloy M. Pally A. Saul C. Wortendyke Minutes of the Regular Meeting Metro-North Committee Monday, April 28, 2014 Meeting Held at 347 Maclison j\.venue New York, New York 10017 8:30 a.m. The following members were present: Hon. Fernando Ferrer, Vice Chairman, MTA Hon. James L. Sedore, Jr., Chairman of the Committee Hon. Mitchell H. Pally Hon. Jonathan A. Ballan Hon. Robert C. Bickford Hon. James F. Blair Hon. Norman Brown Hon. Susan G. Metzger Hon. Charles G. Moerdler Hon. John]. Molloy Hon. Carl V. Wortendyke Not Present: Hon. Jeffrey A. Kay Hon. Andrew M. Saul Also Present Hon. Ira R. Greenberg Hon. Mark D. Lebow Hon. Mark Page Hon. James Redeker, Commissioner, CDOT Joseph]. Giulietti - President, Metro-North Railroad Donna Evans - Chief of Staff Ralph Agritelley- Vice President, Labor Relations Katherine Betries-Kendall- Vice President Human Resources Michael R. Coan - Chief, MTA POllce Department Susan Doering - Vice President-Customer Service & Stations Randall Fleischer - Senior Director, Business Development, Facilities and Marketing James B. Henly - Vice President and General Counsel Michael Horodniceanu, President, MTA Capital Construction John Kesich- Senior Vice President Operations Anne Kirsch - Chief Safety Officer Timothy McCarthy - Senior Director, Capital Programs Kim Porcelain - Vice President - Finance and Information Systems Robert Rodriguez - Director - Diversity and EEO Michael Shiffer - Vice President - Operations Planning Page 3 The members of the Metro-N orth Committee met joindy with the members of the Long Island Committee. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUGUST 1971 VOL. XV NO.4 PUBLISHED SIX TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 WALNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA. 19103 JAMES F . O'GORMAN, PRESIDENT EDITOR: JAMES C. MASSEY , 614 S. LEE STREET, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22314 .. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MRS. MARIAN CARD DONNELLY, 2175 OLIVE STREET, EUGENE, OREGON 97405 SAH NOTICES ORGANIZATIONS Domestic Tours. 1972, H.H. RICHARDSON, HIS CON APT. The Association for Preservation Technology will TEMPORARIES AND HIS SUCCESSORS IN BOSTON AND hold its third General Meeting September 30-0ctober 3 at VICINITY, August 23-27 (Robert B. Rettig, Chairman); Cooperstown, N.Y. SAH member Harley J. McKee is Pres 1973, PHILADELPHIA; 1974, UTICA, NEW YORK and ident. For information and membership ($1 0), write Meredith vicinity. Sykes, Box 2682, Ottawa 4, Ontario, Canada. Foreign Tour. 1972, JAPAN (Bunji Kobayashi, Chairman National Trust. The Trust's Annual Meeting and Preser and Teiji Ito, Co-Chairman). Announcements will reach vation Conference will be in San Diego, California October the membership in the United States and Canada on or 28-31. There will also be a regional preservation con r about September 1, 1971. ference in New Orleans October 15-16. For information 1972 Annual Meeting. San Francisco, January 26-30. address the National Trust for Historic Preservation 740-8 Group Flights : Thirty affirmative responses have been Jackson Place, N .W., Washington, D.C. 20006. received for the Wednesday, January 26 flight New York SAH-GB. The 1971 Annual Conference will be held San Francisco-New York (25 are required); but only 16 re September 10-12 at the University of St. -

Society for Industrial Archeologyทท New England Chapters

Society for Industrial Archeology·· New England Chapters VOLUME23 NUMBER 1 2003 CONTENTS NNEC-SIA Spring 2003 Meeting and Field Tour NNEC-SIA Spring 2003 Meeting and Field Tour Southern New England Chapter The spring meeting and field tour of the Northern New England President's Conunents 2 Northern New England Chapter Chapter, Society for Industrial Archeology, will be held on Saturday, May 10, President's Conunents 3 beginning at 9:30a.m. (if heavy rain on Saturday, then Sunday, May 11). The Field Site Committee Formed for the Northern sites visited will be six in number: three railroad bridges, the remnants of a New England Chapter 3 turntable and locomotive house, a woolen mill, and a granite quarry. From Square Dancing to Folk Engineering: Attendees should arrive at the north end of the Sarah Mildred Long or By A Visit to Thrall Hall 3 Pass U.S. 1 bridge spanning the Piscataqua River between Portsmouth, NH, Adapting to a Changing Steel Economy: and Kittery, ME, no later than 9:40 a.m. on May 10. Directions sent by email A Visit to Berlin Steel 4 Discoveries at the Haverhill-Bath and post will be sufficiently detailed to permit late arrivals to catch the con Covered Bridge 4 voy already heading northwest to the other sites. The registration fee for this History of the New York, New Haven and Hartford tour is $5 per person. Railroad's Central Avenue Interlocking Tower 5 Directions from the south: Proceed on I-95 North (New Hampshire Railroad Roundhouse Archaeology 17 Tpke) to Exit 5, leading to the Portsmouth Traffic Circle. -

Connecticut State Rail Plan, 2012

DRAFT 2012 CONNECTICUT STATE RAIL PLAN __________________________________________________________________ THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK Page 1 DRAFT 2012 CONNECTICUT STATE RAIL PLAN __________________________________________________________________ State of Connecticut Department of Transportation 2012-2016 Connecticut State Rail Plan Prepared by: BUREAU OF PUBLIC TRANSPORATION, OFFICE OF RAIL CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 50 UNION AVENUE, FOURTH FLOOR WEST NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06519 Page 2 DRAFT 2012 CONNECTICUT STATE RAIL PLAN __________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 1 – STATE RAIL VISION, GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES .............................. 9 1.1 MISSION STATEMENT, VISION, AND VALUES ........................................................................ 9 1.2 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES FOR RAIL SERVICE IN CONNECTICUT ..................................... 10 CHAPTER 2 – FEDERAL AND STATE MANDATES .................................................. 13 2.1 FEDERAL LEGISLATION AND PLANNING REQUIREMENTS ................................................ 14 2.2 STATE LEGISLATION AND PLANNING REQUIREMENTS ..................................................... 15 CHAPTER 3 – DESCRIPTION OF RAIL SYSTEM IN CONNECTICUT ....................... 18 -

Metro-North Scenario Pack 01

Realistic Routes and Scenarios for Train Simulator Metro-North Scenario Pack 01 About High Iron Simulations As a Train Simulator Partner Programme member, we collaborate with Dovetail Games to produce a wide variety of realistic content for Train Simulator. Our products now include more than 25 realistic Train Simulator scenario packs, each of which is available at the Steam Store and Dovetail Games Store. Metro-North Commuter Railroad Metro-North Commuter Railroad is one of the United States largest commuter operations, with daily ridership of approximately 300,000 passengers and annual ridership in excess of 87 million. Operating as an entity of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), Metro-North operates three commuter lines from New York City’s Grand Central Terminal — the Hudson Line extending, via Croton-Harmon, to Poughkeepsie, New York; the Harlem Line extending, via White Plains and Brewster, to Wassaic, New York; and the New Haven Line, extending via Stamford, to New Haven, Connecticut. The New Haven Line, operated in cooperation with the Connecticut Department of Transportation, includes branch lines to New Canaan, Danbury, and Waterbury, Connecticut. Metro-North also is a partner with NJ Transit in operating “West of Hudson” lines from Hoboken (New Jersey) Terminal to Spring Valley and Port Jervis, New York. To serve its three routes from Grand Central Terminal, Metro-North utilizes electric-multiple-unit (EMU) trains as well as diesel powered trains hauling Shoreliner “push-pull” equipment. Most diesel-powered trains utilize General Electric P32AC-DM locomotives. EMU trains on the Hudson and Harlem lines most typically employ Metro-North’s M7A electrics while the New Haven Line employs M8 EMUs, the latter of which are equipped to operate both from third-rail D. -

New Haven Line Capacity and Speed Analysis

CTrail Strategies New Haven Line Capacity and Speed Analysis Final Report June 2021 | Page of 30 CTrail Strategies Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 2 2. Existing Conditions: Infrastructure, Facilities, Equipment and Services (Task 1)............... 2 2.1. Capacity and Speed are Constrained by Legacy Infrastructure .................................... 3 2.2. Track Geometry and Slow Orders Contribute to Reduced Speeds ............................... 4 2.3. State-of-Good-Repair & Normal Replacement Improvements Impact Speed .............. 6 2.4. Aging Diesel-Hauled Fleet Limits Capacity ..................................................................... 6 2.5. Service Can Be Optimized to Improve Trip Times .......................................................... 7 2.6. Operating Costs and Revenue ........................................................................................ 8 3. Capacity of the NHL (Task 2)................................................................................................. 8 4. Market Assessment (Task 3) ............................................................................................... 10 4.1. Model Selection and High-Level Validation................................................................... 10 4.2. Market Analysis.............................................................................................................. -

New Ideas for TRANSIT

2011 IDEA Innovations Deserving Exploratory Analysis Programs TRANSIT TRANSIT IDEA PROGRAM ANNUAL REPORT New IDEAS for Transit Transit IDEA Program Annual Progress Report JANUARY 2011 TRB TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE* OFFICERS CHAIR: MICHAEL R. MORRIS, Director of Transportation, North KIRK T. STEUDLE, Director, Michigan Department of Transportation, Central Texas Council of Governments, Arlington Lansing VICE CHAIR: NEIL J. PEDERSEN, Administrator, Maryland State DOUGLAS W. STOTLAR, President and Chief Executive Officer, Con- Highway Administration, Baltimore Way, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: ROBERT E. SKINNER, JR., Transportation C. MICHAEL WALTON, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Research Board Engineering, University of Texas, Austin (Past Chair, 1991) MEMBERS EX OFFICIO MEMBERS J. BARRY BARKER, Executive Director, Transit Authority of River City, PETER H. APPEL, Administrator, Research and Innovative Technology Louisville, Kentucky Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation ALLEN D. BIEHLER, Secretary, Pennsylvania Department of J. RANDOLPH BABBITT, Administrator, Federal Aviation Transportation, Harrisburg Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation LARRY L. BROWN, Sr., Executive Director, Mississippi Department of REBECCA M. BREWSTER, President and COO, American Transportation, Jackson Transportation Research Institute, Smyrna, Georgia DEBORAH H. BUTLER, Executive Vice President, Planning, and CIO, GEORGE BUGLIARELLO, President Emeritus and University Professor, Norfolk