In Search of a New Jerusalem: a Preliminary Investigation Into the Causes and Impact of Welsh Quaker Emigration to Pennsylvania, C.1660 - 1750 Richard C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6364/pennsylvania-county-histories-16364.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

HEFEI 1ENCE y J^L v &fF i (10LLEI JTIONS S —A <f n v-- ? f 3 fCrll V, C3 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun61unse M tA R K TWAIN’S ScRdP ©GOK. DA TENTS: UNITED STATES. GREAT BRITAIN. FRANCE. June 24th, 1873. May i6th, 1877. May i 8th, 1877. TRADE MARKS: UNITED STATES. GREAT BRITAIN. Registered No. 5,896. Registered No. 15,979. DIRECTIONS. Use but little moisture, and only on ibe gummed lines. Press the scrap on without wetting it. DANIEL SLOPE A COMPANY, NEW YORK. IIsTIDEX: externaug from the Plymouth line to the Skippack road. Its lower line was From, ... about the Plymouth road, and its vpper - Hue was the rivulet running to Joseph K. Moore’s mill, in Norriton township. In 1/03 the whole was conveyed to Philip Price, a Welshman, of Upper Datef w. Merion. His ownership was brief. In the same year he sold the upper half, or 417 acres, to William Thomas, another Welshman, of Radnor. This contained LOCAL HISTORY. the later Zimmerman, Alfred Styer and jf »jfcw Augustus Styer properties. In 1706 Price conveyed to Richard Morris the The Conrad Farm, Whitpain—The Plantation •emaining 417 acres. This covered the of John Rees—Henry Conrad—Nathan Conrad—The Episcopal Corporation. present Conrad, Roberts, Detwiler, Mc¬ The present Conrad farm in Whitpain Cann, Shoemaker, Iudehaven and Hoover farms. -

JAMES LOGAN the Political Career of a Colonial Scholar

JAMES LOGAN The Political Career of a Colonial Scholar By E. GORDON ALDERFER* A CROSS Sixth Street facing the shaded lawn of Independence Square in Philadelphia, on the plot now hidden by the pomp- ous facade of The Curtis Publishing Company, once stood a curious little building that could with some justice lay claim to being the birthplace of the classic spirit of early America. Just as the State House across the way symbolizes the birth of independ- ence and revolutionary idealism, the first public home of the Loganian Library could represent (were it still standing) the balanced, serene, inquiring type of mind so largely responsible for nurturing the civilization of the colonies. The Loganian, the first free public library in America outside of Boston and by some odds the greatest collection for public use in the colonial era, was the creation of James Logan, occasionally reputed to have been the most learned man in the colonies during the first half of the eighteenth century. Logan journeyed to Amer- ica with William Penn in 1699 as Penn's secretary, and became in effect the resident head of the province. Two years later, when Penn left his province never to return, Logan was commissioned Secretary of the Province and Commissioner of Property. He was soon installed as Clerk of the Provincial Council and became its most influential member in spite of his youthfulness. Even- tually, in 1731, Logan became Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, and, five years later, as President of the Provincial Council, he assumed *Dr. E. Gordon Alderfer is associated with CARE, Inc., New York, in a research and administrative capacity. -

The History of Bryn Mawr, 1683-1900

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Books, pamphlets, catalogues, and scrapbooks Collections, Digitized Books 1962 The History of Bryn Mawr, 1683-1900 Barbara Alyce Farrow Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons No evidence was found that the copyright was renewed in the 28th year from the date of publication, as required for books published between 1923 and 1963 (see Library of Congress Copyright Office, How To Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work [Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, Copyright Office, 2004]). The book is therefore believed to be in the public domain. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Farrow, Barbara Alyce. The History of Bryn Mawr, 1683-1900. Bryn Mawr, PA: Committee of Residents and Bryn Mawr Civic Association, 1962. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books/14 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The HISTORY OF BRYN MAWR 1683-1900 Barbara Alyce Farrow THE HISTORY OF BRYN MAWR 1683 - 1900 Barbara Alyce Farrow Foreword by Catherine Drinker Bowen Pub lished by A Committee of Residents and The Bryn Mawr Civic Association Bryn M.:lw r, Pe nn sylvania 1962 This work is based on a thesis submitted in 1957 to Westminster College New Wilmington, Pennsylvania. Copyright © Barbara Alyce Farrow 1962 library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-13436 II To my grandmother, Mrs. -

The Role and Importance of the Welsh Language in Wales's Cultural Independence Within the United Kingdom

The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain Scaglia To cite this version: Sylvain Scaglia. The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom. Linguistics. 2012. dumas-00719099 HAL Id: dumas-00719099 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00719099 Submitted on 19 Jul 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2011-2012, 1ère SESSION The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain SCAGLIA Under the direction of Professor Gilles Leydier Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 WALES: NOT AN INDEPENDENT STATE, BUT AN INDEPENDENT NATION ........................................................ -

Audit of Regional Working

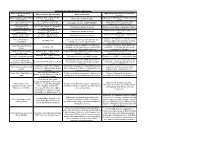

Audit of Regional Working - Place Directorate Name of Regional Group / What are the Benefits to CCoS of this Which Partners are involved? What is the remit? Working Group? Swansea Bay City Deal Officer Swansea, NPT, Carms, Pembs, Significant investment, job creation, economic Deliver the City Deal Projcets Working Group Ceredigion, Powys growth RDP South West & Central NPT, Swansea, Carmarthen, awareness of activity, delivery, risks, Information exchange of RDP LEADER Local Action Group Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion, Powys evaluation and expansion of RDP Workways + ESF NPT (lead), Swansea, Carmarthen, Management groups for project Management of major employability initiative employability project Pembs, Ceredigion Cynydd ESF young people Pembs (Lead), Swansea, Management of major youth engagement Management groups for project support project Carmarthen, NPT, Ceredigion project Cam Nesa ESF NEETs Pembs (Lead), Swansea, Management of major NEET engagement Management groups for project Employability Project Carmarthen, NPT, Ceredigion project Contibute to development of new WG Valleys Valleys Task Force - to develop each concept outlined in the “Our All Valleys LA's strategy; could be linked to future funding Landscapes Valleys, Our Future” high level plan opporutnities for north Swansea Meeting of officers engaged in securing and Exchange of information and good practice, Welsh European Funding All Wales LA's managing external funding sources such as EU constructive networking with other Local Group funding, HLF, WG capital funding etc authorities, -

Wales at Westminster: Parliament, Principality and Pressure Groups, 1542-1601*

Parliamentary History, Vol. 22, pt. 2 (2003), pp. 107-120 Wales at Westminster: Parliament, Principality and Pressure Groups, 1542-1601* LLOYD BOWEN Cdif University This article attempts to address an inconsistency of modern historiography regarding the legacy of Wales’s union with England in the mid-sixteenth century. The discrepancy concerns the participation of Welshmen in the new parliamentary and administrative roles afforded by the union. The Henrician statutes which united Wales with England remodelled Welsh justice and administration, bringing Wales into line with English practice. Justices of the peace were introduced, Wales was divided into shires like England, and, in the most symbolically significant demon- stration of the incorporation of Wales into the English body politic, 26 (later 27) Welsh borough and county constituencies were enfranchised and allowed to send representatives to the national parliaments at Westminster.’ However, the speed of the reception and adoption of these new rights by Welshmen has not been seen as uniform. Whereas they are often portrayed as embracing their new administrative roles quickly and with enthusiasm, their participation in parliamentary business is seen as halting, uncertain and ineffective.2 This generally has led to the characteri- zation of the Welsh as lacking interest in parliament and continuing to be unsure of its mechanisms and procedures for many decades after their enfiran~hisement.~ This article examines how the ‘two-speed’ adoption of the union has become an accepted element of modern historiography, and suggests that this case has been overstated. The picture of a hesitant body of Welsh members in the Tudor Commons is attributable mainly to Professor A. -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Directory of Cancer Support Services in South West Wales. 2010-2011

Directory of Cancer Support Services in South West Wales. 2010-2011 Self Help and Support Groups Voluntary Sector Hospice and Palliative Care Providers South West Wales Cancer Network 2010 Prepared by Helen Dorman, Macmillan Patient Involvement Facilitator SOUTH WEST WALES CANCER NETWORK SELF HELP / SUPPORT GROUPS NAME & ADDRESS INFORMATION TELEPHONE NUMBER The Beacon of Hope. A small team of professionals Aberystwyth. and volunteers working for 01970 615593 Cardigan a charity; providing immediate 01239 614989 comfort and on-going practical support to people with a life limiting or terminal illness in Ceredigion Pembrokeshire Meetings held on the2nd 01437 710376 Breast Cancer Friday of every month, 01437 720496 Support Group. between 10:30-12:30 The Community Providing support for those Centre, diagnosed with breast cancer Furzy Park, in Pembrokeshire Haverfordwest Tawe Valley Breast Support and Information. 01158 822554 Care Support Group. Secretary, Mair Griffith 01558 822588 Pembrokeshire Registered Charity. Barbara/ Jill Cancer Support. Provides Support &Information 01646 683078 for those who have or have had cancer together with their family and friends . Llanelli Breast Meet every 3 rd . Monday of the Jean 01554 Cancer Support month except in August. 810967 Group Provides support and Dilys (Welsh friendship. Speaker) 01554 758413 Breast Cancer Care. Support and advice Valerie Carmarthen Pearson 01559 384854 Stepping Stones A support group for women Angela Hamer Breast Support who meet in conjunction with 01686 624702 Group Macmillan Nurses, every Ist. Mary Newtown, Mid Wednesday of the month at 01938 558047 Powys 19:00 at The Hafan Day Unit, Newtown Hospital NAME & ADDRESS INFORMATION TELEPHONE NUMBER Breast of Friends Support and Information Janet Williams Breast Support 01686 412778 Group Llanidloes, Mid Powys Breast Cancer Information and advice Ffion Davies Group Community The Black Mountain Developmental Centre, Officer Cwmgarw Road, Brynaman 01269 823400 Carmarthenshire Llandeilo Breast Information and support Diane Rocca Cancer Group. -

New Haven Friends Meeting November 2020 Starter List of Resources to Find out More About Quakers and Quakerism

New Haven Friends Meeting November 2020 Starter list of resources to find out more about Quakers and Quakerism The History of Friends: Most of the following resources are available through QuakerBooks of FGC or the Pendle Hill online bookstore. • Friends for 350 Years, Howard Brinton • Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship: Quakers, African Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice, Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye • Silence and Witness: The Quaker Tradition, Michael Birkel • Journal of George Fox • Journal of John Woolman • The Quiet Rebels: The Story of the Quakers in America, Margaret Hope Bacon • Portrait in Grey: A Short history of the Quakers, John Punshon • Quaker.org history section • How Quakerism Began, QuakerSpeak video Quaker Faith and Practice: • QuakerSpeak video on Testimonies: The Quaker Spices • New England Yearly Meeting (NEYM): Faith and Practice • A Testament of Devotion, Thomas R. Kelly • A Procession of Friends: Quakers in America, Daisy Newman • Friends Journal • 2014 Swarthmore Lecture (video), University of Bath, Ben Pink Dandelion • Pendle Hill Pamphlets in general, and specifically The Nature of Quakerism, by Howard H. Brinton Witness into Action: • Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin (film) • The Vote, PBS series that mentions Alice Paul • A Journey Toward Eliminating Racism in the Religious Society of Friends, Vanessa Julye • QuakerSpeak video: Holding the Peace: Quaker Nonviolence in the Time of Black Lives Matter • New England Yearly Meeting’s Priorities for 2020-2021 o 2016 Minutes on Climate Change o A Letter of Apology to Indigenous Peoples (under revision) and a Call for Us to Act: https://neym.org/working-group-right-relationship-indigenous-peoples o A Call to Urgent Loving Action for the Earth and Her Inhabitants, which names the interconnected nature of “systemic problems of racism, social injustice, violence, greed, and failure to act on the climate crisis.” o The Outgoing Epistle of the 2020 Virtual Pre-Gathering of Friends of Color and their Families, Friends General Conference (FGC) . -

Religion and the Abolition of Slavery: a Comparative Approach

Religions and the abolition of slavery - a comparative approach William G. Clarence-Smith Economic historians tend to see religion as justifying servitude, or perhaps as ameliorating the conditions of slaves and serving to make abolition acceptable, but rarely as a causative factor in the evolution of the ‘peculiar institution.’ In the hallowed traditions, slavery emerges from scarcity of labour and abundance of land. This may be a mistake. If culture is to humans what water is to fish, the relationship between slavery and religion might be stood on its head. It takes a culture that sees certain human beings as chattels, or livestock, for labour to be structured in particular ways. If religions profoundly affected labour opportunities in societies, it becomes all the more important to understand how perceptions of slavery differed and changed. It is customary to draw a distinction between Christian sensitivity to slavery, and the ingrained conservatism of other faiths, but all world religions have wrestled with the problem of slavery. Moreover, all have hesitated between sanctioning and condemning the 'embarrassing institution.' Acceptance of slavery lasted for centuries, and yet went hand in hand with doubts, criticisms, and occasional outright condemnations. Hinduism The roots of slavery stretch back to the earliest Hindu texts, and belief in reincarnation led to the interpretation of slavery as retribution for evil deeds in an earlier life. Servile status originated chiefly from capture in war, birth to a bondwoman, sale of self and children, debt, or judicial procedures. Caste and slavery overlapped considerably, but were far from being identical. Brahmins tried to have themselves exempted from servitude, and more generally to ensure that no slave should belong to 1 someone from a lower caste. -

Consumption Patterns and Outward Expression of Quakers As Seen Through Historical Documentation and 18Th Century York County, Virginia Probate Inventories

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 For Profit and unction:F Consumption Patterns and Outward Expression of Quakers as Seen through Historical Documentation and 18th Century York County, Virginia Probate Inventories Darby O'Donnell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation O'Donnell, Darby, "For Profit and unction:F Consumption Patterns and Outward Expression of Quakers as Seen through Historical Documentation and 18th Century York County, Virginia Probate Inventories" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626355. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mznr-rn68 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOR PROFIT AND FUNCTION: CONSUMPTION PATTERNS AND OUTWARD EXPRESSION OF QUAKERS AS SEEN THROUGH HISTORICAL DOCUMENTATION AND 18 th CENTURY YORK COUNTY, VIRGINIA PROBATE INVENTORIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Darby O’Donnell 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Darby Q Donnell Approved, March 2002 Norman F. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] A Letter From William Penn Proprietary and Governour of Pennsylvania In America, To The Committee of the Free Society of Traders of That Province, residing in London. with a Portraiture or Plat-form thereof . 1683 (First Map of Philadelphia) Stock#: 37576a Map Maker: Holme Date: 1683 Place: London Color: Uncolored Condition: VG Size: 10 x 7 inches Price: SOLD Description: A foundational document of Colonial America, with the first printed map of a North American City. William Penn's Letter… (1683) includes the first printed map of the city and the earliest design for a planned community in America. It is a critical primary document relating to the foundation of Pennsylvania, and one of the most important 17th Century imprints relating to America. The map is accompanied by the printed Letter... by William Penn, Pennsylvania's founder, explaining and promoting his new colony to prospective investors and settlers. It also includes the original Advertisement... by Thomas Holme, Penn's official surveyor, explaining his map of Philadelphia. The following is a link to the map: {{ inventory_enlarge_link('37576a') }} William Penn, Thomas Holme and the Foundation of Philadelphia William Penn (1644-1718) was a Quaker convert and the son of English Admiral Sir William Penn (1711-70). Much of Penn's early adulthood had been spent promoting Quakerism, a doctrinally strict but, in many ways, socially enlightened sect of Christianity. While estranged from his father and persecuted by royal authorities over his religious beliefs, Penn nevertheless inherited his father's estate and the large debt owed to Sir William by Charles II.