Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kilgetty/Begelly Community Council - Kilgetty Ward Cyngor Cymuned Cilgeti/Begeli - Ward Cilgeti

ELECTION OF COMMUNITY COUNCILLORS ETHOLIAD CYNGHORWYR CYMUNED 4 MAY 2017 / 4 MAI 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election for the Mae’r canlynol yn ddatganiad am y personau a enwebwyd cael ei/eu (h)ethol ar gyfer KILGETTY/BEGELLY COMMUNITY COUNCIL - KILGETTY WARD CYNGOR CYMUNED CILGETI/BEGELI - WARD CILGETI STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED DATGANIAD AM Y PERSONAU A ENWEBWYD 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Surname / Other Home Address Description Names of Proposer Decision of Returning Officer that Cyfenw Names / (in full) (if any) and Seconder Nomination Paper is invalid or other reason why a person Enwau Cyfeiriad Cartref Disgrifiad Enwau y Bobl a nominated no longer stands Eraill (yn llawn) (os oes un) Lofnododd y Papur nominated Penderfyniad y Swyddog Enwebu Canlyniadau fod y papur yn ddirym neu reswm arall paham na chaiff person a enwebwyd barhau i fod felly Renate D Boone ANDREWS Trevor 2 Heritage Gardens Arthur Kilgetty Janet D Ward Pembrokeshire SA68 0TW Independent Janet D Ward LOCKLEY Diane Churchlands Farm Christine Reynalton Trevor A Andrews Kilgetty Pembrokeshire SA68 0PE David J Pugh SMITH Sandra Mary Cozy Nook 27 Oakfield Drive Susan Rees Kilgetty Pembrokeshire SA68 0UD Trevor A Andrews WARD Janet Diane Little Oaks Ryelands Way Jeanette E Andrews Kilgetty Pembrokeshire SA68 0US Sandra M Smith WOODGATE Josephine 15 Park Avenue Mary Kilgetty Peter G Gilder Pembrokeshire SA68 0UB The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in column 6, have been and stand validly nominated. Y mae’r personau nad oes cofnod gyferbyn a’u henwau yng ngholofn 6, wedi’u henwebu’n gyfreithlon, ac yn parhau i fod felly. -

Benthic Habitat Mapping of Cardigan Bay, in Relation to the Distribution of the Bottlenose Dolphin

Benthic Habitat Mapping of Cardigan Bay, in relation to the distribution of the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). A dissertation submitted in part candidature for the Degree of B.Sc., Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Wales, Aberystwyth. By Hannah Elizabeth Vallin © Sarah Perry May 2011 1 Acknowledgments I would like to give my thanks to several people who made contributions to this study being carried out. Many thanks to be given firstly to the people of Cardigan Bay Marine Wild life centre who made this project possible, for providing the resources and technological equipment needed to carry out the investigation and for their wealth of knowledge of Cardigan Bay and its local wildlife. With a big special thanks to Steve Hartley providing and allowing the survey to be carried out on board the Sulaire boat. Also, to Sarah Perry for her time and guidance throughout, in particular providing an insight to the OLEX system and GIS software. To Laura Mears and the many volunteers that contributed to participating in the sightings surveys during the summer, and for all their advice and support. I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor Dr. Helen Marshall for providing useful advice, support, and insightful comments to writing the report, as well as various staff members of Aberystwyth University who provided educational support. Finally many thanks to my family and friends who have supported me greatly for the duration. Thankyou. i Abstract The distribution and behaviour of many marine organisms such the bottlenose dolphin Tursiops truncates, are influenced by the benthic habitat features, environmental factors and affinities between species of their surrounding habitats. -

Amaeth Cymru the Future of Agriculture in Wales: the Way Forward

Amaeth Cymru The future of agriculture in Wales: the way forward Amaeth Cymru The future of agriculture in Wales: the way forward Contents 1. Introduction to Amaeth Cymru 3 2. Our ambition 4 3. The outcomes 5 4. Links to other groups and sectors 5 5. Where are we now? 6 Global trends 6 The Welsh agriculture industry 6 Key imports and exports 7 Wider benefits of agriculture 7 Current support payments 8 Environment (Wales) Act 8 6. The impact of exiting the EU 9 Opportunities and threats presented by EU exit 9 7. The way forward 10 Overarching requirements 10 Measures to deliver more prosperity 10 Measures to deliver more resilience 11 8. Conclusion 12 Annex 1: Evidence paper – the Welsh agriculture sector 14 Annex 2: Amaeth Cymru – Market Access Position Paper 18 Annex 3: SWOT Analysis 21 Annex 4: List of sources 24 WG33220 © Crown copyright 2017 Digital ISBN 978-1-78859-881-1 2 Amaeth Cymru Amaeth Cymru 3 1. Introduction to Amaeth Cymru ¬ Amaeth Cymru – Agriculture Wales was This document sets out our Vision for Welsh established on 25 September 2015 following Agriculture, the associated outcomes, an a Welsh Government consultation on a overview of where the industry is currently Strategic Framework for Welsh Agriculture.i and the strategic priorities that we will need This consultation was based around a to address to achieve that Vision. ‘principles paper’ developed by leading industry stakeholders and took into account This document is set within the context of the work of various independent reviewers. Taking Wales Forward – the government’s programme to drive improvement in Amaeth Cymru is an industry-led group, the Welsh economy and public services, with Welsh Government as an equal partner. -

Code Compliance Data Pdf 275 Kb

STANDARDS COMMITTEE 13/09/19 CODE COMPLIANCE DATA Recommendations / key decisions required: To consider the report Reasons: The subject matter of this report falls within the remit of the Committee Scrutiny Committee recommendations / comments: Not applicable Exec Board Decision Required NO Council Decision Required NO EXECUTIVE BOARD MEMBER PORTFOLIO HOLDER:- Cllr E Dole (Leader) Directorate Chief Executives Name of Head of Service: Designations: Linda Rees-Jones Head of Administration & Law Tel Nos. Report Author: 01267 224018 Robert Edgecombe Legal Services Manager E Mail Addresses: [email protected]. uk. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY STANDARDS COMMITTEE 13/0919 CODE COMPLIANCE DATA The Standards Committee receives an annual report (usually at its December meeting) as to the level of code compliance by Town and Community Councillors during the preceding municipal year. The report captures; 1. Number of code complaints to the Ombudsman 2. Number of declarations of interest 3. Number of dispensation applications 4. Whether any councillors have received code training Unfortunately a significant number of Councils do not respond to written requests for this information. At its meeting in March 2019 the committee requested regular updates as to the number of responses received. As at the date of writing this report 53 out of 72 councils had responded. Those who have not responded are; Abernant, Ammanford Town, Bronwydd, Cynwyl Elfed, Dyffryn Cennen, Eglwys Gymyn, Laugharne Township, Llanarthne, Llanfihangel Rhos Y Corn, Llangathen, Llanllwni, Llanpumpsaint, Llansadwrn, Llansteffan & Llanybri, Llanwrda, Meidrim, Pencarreg, Pendine, Pontyberem, and St.Ishmael. Of these, St Ishmael, Meidrim, Llanwrda, Llansteffan & Llanybri, Llansadwrn, Llanpumpsaint, Llanfihangel-Rhos-Y-Corn and Llanarthne have not provided a response for the last 2 years and Eglwys Gymyn, Bronwydd and Abernant have not provided a response for the last 3 years. -

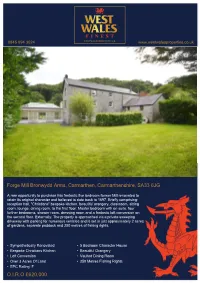

Vebraalto.Com

0845 094 3024 www.westwalesproperties.co.uk Forge Mill Bronwydd Arms, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, SA33 6JG A rare opportunity to purchase this fantastic five bedroom former Mill renovated to retain its original character and believed to date back to 1697. Briefly comprising: reception hall, "Christians" bespoke kitchen, beautiful orangery, cloakroom, sitting room, lounge, dining room, to the first floor: Master bedroom with en suite, four further bedrooms, shower room, dressing room and a fantastic loft conversion on the second floor. Externally: The property is approached via a private sweeping driveway with parking for numerous vehicles and is set in just approximately 2 acres of gardens, separate paddock and 250 metres of fishing rights. • Sympathetically Renovated • 5 Bedroom Character House • Bespoke Christians Kitchen • Beautiful Orangery • Loft Conversion • Vaulted Dining Room • Over 3 Acres Of Land • 250 Metres Fishing Rights • EPC Rating: F O.I.R.O £620,000 Forge Mill Bronwydd Arms, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, SA33 6JG LOCATION The hamlet of Bronwydd situated just 6.5 miles from Carmarthen town, has all the tranquillity of a rural village with all the benefits of the County town. The village is most famous for its Gwili Steam railway, transporting you back to another time. The village is accessed by A and B Roads and is regularly served by buses to Carmarthen and on to Cardigan. Carmarthen being the closest county town has everything you could need for modern day living, its market, shopping and restaurants all having undergone modernising and expansion over the last few years increasing desirability in the local area. A LITTLE PIECE OF HISTORY Thought to date back to 1697, this fantastic former mill can be found in many local History books. -

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean's Annual Report

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean’s Annual Report Fiscal Year 2011 Harvard University 1 Table of Contents Harvard College ........................................................................................................................... 9 Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) ......................................................................... 23 Division of Arts and Humanities ................................................................................................ 29 Division of Science .................................................................................................................... 34 Division of Social Science ......................................................................................................... 38 School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) ............................................................... 42 Faculty Trends ............................................................................................................................ 49 Harvard College Library ............................................................................................................ 54 Sustainability Report Card ......................................................................................................... 59 Financial Report ......................................................................................................................... 62 2 Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Office of the Dean University Hall Cambridge, Massachusetts -

Suzal, Bronwydd Arms, Carmarthen SA33

Suzal, Bronwydd Arms, Carmarthen SA33 6BD Offers in the region of £220,000 • Spacious Three Double Bedroom Bungalow • Popular Location Four Miles From Carmarthen • Driveway Parking, Double Garage • Viewing Recommended John Francis is a trading name of Countrywide Estate Agents, an appointed representative of Countrywide Principal Services Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, fittings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is verified by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also confirm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. CR/RO/65844/060918 integrated dishwasher, 1½ backs onto Bronwydd cricket bowl sink with drainer and club. DESCRIPTION mixer tap, localised wall Situated in the popular tiles, tiled floor, door to; SERVICES village of Bronwydd, on a We have been advised that good sized level plot with REAR HALL the mains electricity and driveway parking and double Door to the side hall, build-in water are connected to the garage. -

THE ROLE of GRAZING ANIMALS and AGRICULTURE in the CAMBRIAN MOUNTAINS: Recognising Key Environmental and Economic Benefits Delivered by Agriculture in Wales’ Uplands

THE ROLE OF GRAZING ANIMALS AND AGRICULTURE IN THE CAMBRIAN MOUNTAINS: recognising key environmental and economic benefits delivered by agriculture in Wales’ uplands Author: Ieuan M. Joyce. May 2013 Report commissioned by the Farmers’ Union of Wales. Llys Amaeth,Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 3BT Telephone: 01970 820820 Executive Summary This report examines the benefits derived from the natural environment of the Cambrian Mountains, how this environment has been influenced by grazing livestock and the condition of the natural environment in the area. The report then assesses the factors currently causing changes to the Cambrian Mountains environment and discusses how to maintain the benefits derived from this environment in the future. Key findings: The Cambrian Mountains are one of Wales’ most important areas for nature, with 17% of the land designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). They are home to and often a remaining stronghold of a range of species and habitats of principal importance for the conservation of biological diversity with many of these species and habitats distributed outside the formally designated areas. The natural environment is critical to the economy of the Cambrian Mountains: agriculture, forestry, tourism, water supply and renewable energy form the backbone of the local economy. A range of non-market ecosystem services such as carbon storage and water regulation provide additional benefit to wider society. Documentary evidence shows the Cambrian Mountains have been managed with extensively grazed livestock for at least 800 years, while the pollen record and archaeological evidence suggest this way of managing the land has been important in the area since the Bronze Age. -

Dyfed Final Recommendations News Release

NEWS RELEASE Issued by the Telephone 02920 395031 Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House Fax 02920 395250 1-6 St Andrews Place Cardiff CF10 3BE Date 25 August 2004 FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN THE PRESERVED COUNTY OF DYFED The Commission propose to make no change to their provisional recommendations for five constituencies in the preserved county of Dyfed. 1. Provisional recommendations in respect of Dyfed were published on 5 January 2004. The Commission received eleven representations, five of which were in support of their provisional recommendations. Three of the representations objected to the inclusion of the whole of the Cynwyl Elfed electoral division within the Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire constituency, one objected to the name of the Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire constituency and one suggested the existing arrangements for the area be retained. 2. The Commission noted that, having received no representation of the kind mentioned in section 6 (2) of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, there was no statutory requirement to hold a local inquiry. The Commission further decided that in all the circumstances they would not exercise their discretion under section 6 (1) to hold an inquiry. Final recommendations 3. The main objection to the provisional recommendations was in respect of the inclusion of the Cynwyl Elfed electoral division in the Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire constituency. It was argued that the division should be included in Carmarthen East and Dinefwr on the grounds that the majority of the electorate in the division fell within that constituency and that inclusion in Carmarthen East and Dinefwr rather than Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire would reduce the disparity between the electorates of the two constituencies and would bring them closer to the electoral quota. -

Note to User

NOTE TO USER Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This is reproduction is the best copy available THE NUTRIENT AND PHYTONUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF ONTARIO GROWBEANS AND =IR EFFECT ON AZOXYMETHANE INDUCED COLONTC PRENEOPLASIA IN RATS Heten Anita MiUie Samek A thesis submitted in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto Copyright by Helen Anita Millie Samek 200 1 Acquisitions and Acquisit'hs et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliiraphiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowhg the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to BkIiothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auîeur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenivise de ceile-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TEE NUTRIENT AND PaYTONUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF ONTARIO GROWN BEANS AND THEIR EFFECT ON AZOXYMETHANE INDUCED COLONIC PRENEOPLASIA IN RATS Master of Science, 200 1 Helen A. Samek Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto Beans have long been recognized for their nutritionai quality. -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Llysdinam Estate Records, (GB 0210 LLYSDINAM) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/llysdinam-estate-records archives.library .wales/index.php/llysdinam-estate-records Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Llysdinam Estate Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Wales: River Wye to the Great Orme, Including Anglesey

A MACRO REVIEW OF THE COASTLINE OF ENGLAND AND WALES Volume 7. Wales. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey J Welsby and J M Motyka Report SR 206 April 1989 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX1 0 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT This report reviews the coastline of south, west and northwest Wales. In it is a description of natural and man made processes which affect the behaviour of this part of the United Kingdom. It includes a summary of the coastal defences, areas of significant change and a number of aspects of beach development. There is also a brief chapter on winds, waves and tidal action, with extensive references being given in the Bibliography. This is the seventh report of a series being carried out for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. For further information please contact Mr J M Motyka of the Coastal Processes Section, Maritime Engineering Department, Hydraulics Research Limited. Welsby J and Motyka J M. A Macro review of the coastline of England and Wales. Volume 7. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey. Hydraulics Research Ltd, Report SR 206, April 1989. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COASTAL GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.1 Geological background 3.2 Coastal processes 4 WINDS, WAVES AND TIDAL CURRENTS 4.1 Wind and wave climate 4.2 Tides and tidal currents 5 REVIEW OF THE COASTAL DEFENCES 5.1 The South coast 5.1.1 The Wye to Lavernock Point 5.1.2 Lavernock Point to Porthcawl 5.1.3 Swansea Bay 5.1.4 Mumbles Head to Worms Head 5.1.5 Carmarthen Bay 5.1.6 St Govan's Head to Milford Haven 5.2 The West coast 5.2.1 Milford Haven to Skomer Island 5.2.2 St Bride's Bay 5.2.3 St David's Head to Aberdyfi 5.2.4 Aberdyfi to Aberdaron 5.2.5 Aberdaron to Menai Bridge 5.3 The Isle of Anglesey and Conwy Bay 5.3.1 The Menai Bridge to Carmel Head 5.3.2 Carmel Head to Puffin Island 5.3.3 Conwy Bay 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY FIGURES 1.