News Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Index September 1976-August 1977 Vol. 3

INDEX I- !/oluJne3 Numbers 1-12 ONANTIQUES , September, 1976-August, 1977 AND COLLECTABLES Pages 1-144 PAGES ISSUE DATE 1-12 No.1 September, 1976 13-24 No.2 October, 1976 25-36 No.3 November, 1976 37-48 No.4 December, 1976 49-60 No.5 January, 1977 61-72 No.6 February, 1977 & Kovel On became Ralph Terry Antiques Kovels 73-84 No.7 March,1977 On and Antiques Collectables in April, 1977 (Vol. 85-96 No.8 April,1977 3, No.8). , 97-108 No.9 May, 1977 Amberina glass, 91 109-120 No� 10 June, 1977 Americana, 17 121-132 No.l1 July, 1977 American Indian, 30 133-144 No. 12 August, 1977 American Numismatic Association Convention, 122 Anamorphic Art, 8 Antique Toy World, 67 in Katherine ART DECO Antiques Miniature, by Morrison McClinton, 105 Furniture, 38, 88 Autumn The 0 Glass, 88 Leaf Story, by J Cunningham, 35 Metalwork, 88 Avons other Dee Bottles-by any name, by Sculpture, 88 Schneider, 118 Art 42 Nouveau, 38, Avons Award Bottles, Gifts, Prizes, by Dee' Art Nouveau furniture, 38 Schneider, 118 "Auction 133 & 140 Avons Fever," Bottles Research and History, by Dee 118 Autographs, 112 Schneider, Avons Dee 118 Banks, 53 Congratulations, -by Schneider, Avons President's Club Barometers, 30 History, Jewelry, by Bauer 81 Dee 118 pottery, Schneider, Bauer- The California Pottery Rainbow, by Bottle Convention, 8 Barbara Jean Hayes, 81 Bottles, 61 The Beer Can-A Complete Guide to Collecting, Books, 30 by the Beer Can Collectors of America, 106 BOOKS & PUBLICATIONS REVIEWED The Beer Can Collectors News Report, by the Abage Enclyclopedia of Bronzes, Sculptors, & Beer Can Collectors of America, 107 Founders, Volumes I & II, by Harold A Beginner's Guide to Beer Cans, by Thomas Berman, 52 Toepfer, 106 American Beer Can Encyclopedia, by Thomas The Belleek Collector's Newsletter the ' by Toepfer, 106 Belleek Collector's Club, 23- American Copper and Brass, by Henry J. -

Using Color As Expression

MUSEUM LEARNING: PLANS & RESOURCES Using Color as Expression We are going to explore colors, how we see them, and the ways we can mix them to create amazing art. By exploring an important painting at Shelburne Museum–The Grand Canal, Venice (Blue Venice) painted by Edouard Manet in 1875, we will look closely at how the artist used color to create his masterpiece. Goals We will learn some art vocabulary to identify color schemes, explore Manet’s techniques and create our own version of Manet’s The Grand Canal, Venice painting. Edouard Manet, The Grand Canal, Venice (detail), 1875. Oil on canvas, Background Information 23 1/8 x 28 1/8 in. Gift of the Electra Havemeyer Webb Fund, Inc. 1972 69.15. In 1875, Manet painted this view on the Grand Canal, which H. O. Havemeyer purchased for his wife Louisine 20 years later. She was particularly fond of More Resources the picture and changed its name to Blue Venice. Mrs. Havemeyer wrote that her friend Mary Cassatt n Edouard Manet (1832-83), The Met, “congratulated us when we bought this picture, https://bit.ly/`met-SM saying she considered it one of Manet’s most brilliant n What’s the Difference between Manet and Monet, works; it was so full of light and atmosphere and The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty, expressed the very soul and spirit of Venice.” Her https://bit.ly/Getty2-SM daughter Electra Havemeyer Webb inherited Blue n Impressionism: Art & Modernity, The Met, Venice, which hangs in the living room of her New https://bit.ly/met1-SM York City apartment, reinstalled in Shelburne Museum’s Memorial Building. -

RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS by Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee

Field Notes - Spring 2016 Issue RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS By Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee We have been reviewing new books about the Olmsteds and the art of landscape architecture for so long that the book section of our website is beginning to resemble a bibliography. To make this resource more useful for researchers and interested readers, we’re beginning a series of articles about older publications that remain useful and enjoyable. We hope to focus on the landmarks of the Olmsted literature that appeared before the creation of our website as well as shorter writings that were not intended to be scholarly works or best sellers but that add to our understanding of Olmsted projects and themes. THE OLMSTEDS AND THE VANDERBILTS The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations 1879-1901. by John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson, Introduction by Louis Auchincloss. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991, 341 pages. At his death, William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) was the richest man in America. In the last eight years of his life, he had more than doubled the fortune he had inherited from his father, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), who had created an empire from shipping and then done the same thing with the New York Central Railroad. William Henry left the bulk of his estate to his two eldest sons, but each of his two other sons and four daughters received five million dollars in cash and another five million in trust. This money supported a Vanderbilt building boom that remains unrivaled, including palaces along Fifth Avenue in New York, aristocratic complexes in the surrounding countryside, and palatial “cottages” at the fashionable country resorts. -

SORS-2021-1.2.Pdf

Office of Fellowships and Internships Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC The Smithsonian Opportunities for Research and Study Guide Can be Found Online at http://www.smithsonianofi.com/sors-introduction/ Version 1.1 (Updated August 2020) Copyright © 2021 by Smithsonian Institution Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 How to Use This Book .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Anacostia Community Museum (ACM) ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Archives of American Art (AAA) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (CFCH) ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum (CHNDM) ............................................................................................................................. -

LOTNUM LEAD DESCRIPTION 1 Sylvester Hodgdon "Castle Island" Oil on Canvas 2 Hampshire Pottery Green Handled Vase 3

LOTNUM LEAD DESCRIPTION 1 Sylvester Hodgdon "Castle Island" oil on canvas 2 Hampshire Pottery Green Handled Vase 3 (2) Pair of Brass Candlesticks 4 (2) Cast Iron Horse-Drawn Surrey Toys 5 (4) Glass Pieces w/Lalique 6 18th c. Tilt-Top Table 7 (2) Black Painted Children's Chairs 8 Corner Chair 9 Vitrine Filled with (21) Jasperware Pieces and Planter 10 Bannister Back Armchair 11 (4) Pieces of Colored Art Glass 12 (8) Pieces of Amethyst Glass 13 "Ship Mercury" 19thc. Port Painting 14 (18) Pieces of Jasperware 15 Inlaid Mahogany Card Table 16 Lolling Chair with Green Upholstery 17 (8) Pieces of Cranberry Glass 18 (2) Child's Chairs (1) Caned (1) Painted Black 19 (16) Pieces of Balleek China 20 (13) Pieces of Balleek China 21 (32) Pieces of Balleek China 22 Over (20) Pieces of Balleek China 23 (2) Foot Stools with Needlepoint 24 Table Fitted with Ceramic Turkey Platter 25 Pair of Imari Lamps 26 Whale Oil Peg Lamp 27 (2) Blue and White Export Ceramic Plates 28 Michael Stoffa "Thatcher's Island" oil w/ (2) other Artworks 29 Pair of End Tables 30 Custom Upholstered Sofa 31 Wesley Webber "Artic Voyage 1879" oil on canvas 32 H. Crane "Steam Liner" small gouache 33 E. Sherman "Steam Liner in Harbor" oil on canvas board 34 Oil Painting "Boston Light" signed FWS 35 Pair of Figured Maple Chairs 36 19th c. "Ships Sailing off Lighthouse" oil on canvas 37 Pate Sur Pate Cameo Vase 38 (3) Framed Artworks 39 (3) Leather Bound Books, Box and Pitcher 40 Easy Chair with Pillows 41 Upholstered Window Bench 42 Lot of Games 43 Rayo-Type Electrified Kerosene Lamp 44 Sextant 45 (11) Pieces of Fireplace Equipment and a Brass Bucket 46 (9) Pieces of Glass (some cut) 47 High Chest 48 Sewing Stand 49 (3) Chinese Rugs 50 "Lost at Sea" oil on canvas 51 Misc. -

A Mechanism of American Museum-Building Philanthropy

A MECHANISM OF AMERICAN MUSEUM-BUILDING PHILANTHROPY, 1925-1970 Brittany L. Miller Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Departments of History and Philanthropic Studies, Indiana University August 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________________ Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D., J.D., Chair ____________________________________ Dwight F. Burlingame, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the same way that the philanthropists discussed in my paper depended upon a community of experienced agents to help them create their museums, I would not have been able to produce this work without the assistance of many individuals and institutions. First, I would like to express my thanks to my thesis committee: Dr. Elizabeth Monroe (chair), Dr. Dwight Burlingame, and Dr. Philip Scarpino. After writing and editing for months, I no longer have the necessary words to describe my appreciation for their support and flexibility, which has been vital to the success of this project. To Historic Deerfield, Inc. of Deerfield, Massachusetts, and its Summer Fellowship Program in Early American History and Material Culture, under the direction of Joshua Lane. My Summer Fellowship during 2007 encapsulated many of my early encounters with the institutional histories and sources necessary to produce this thesis. I am grateful to the staff of Historic Deerfield and the thirty other museums included during the fellowship trips for their willingness to discuss their institutional histories and philanthropic challenges. -

List of Articles

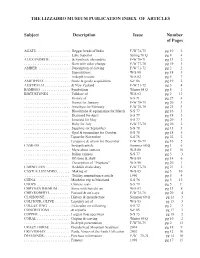

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

(Together “Knife Rights”) Respectfully Offer the Following Comments In

Knife Rights, Inc. and Knife Rights Foundation, Inc. (together “Knife Rights”) respectfully offer the following comments in opposition to the proposed rulemaking revising the rule for the African elephant promulgated under § 4(d) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (“ESA”) (50 C.F.R. 17.40(e)) by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“the Agency”). Docket No. FWS–HQ–IA–2013–0091; 96300–1671–0000–R4 (80 Fed. Reg. 45154, July 29, 2015). Knife Rights represents America's millions of knife owners, knife collectors, knifemakers, knife artisans (including scrimshaw artists and engravers) and suppliers to knifemakers and knife artisans. As written, the proposed rule will expose many individuals and businesses to criminal liability for activities that are integral to the legitimate ownership, investment, collection, repair, manufacture, crafting and production of knives. Even where such activities may not be directly regulated by the proposed rule, its terms are so vague and confusing that it would undoubtedly lead to excessive self-regulation and chill harmless and lawful conduct. The Agency’s proposed revisions to the rule for the African Elephant under section 4(d) of the ESA (“the proposed rule”) must be withdrawn, or in the alternative, significantly amended to address these terminal defects: (1) Violations of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) (Pub. L. 79–404, 60 Stat. 237) and 5 U.S.C. § 605(b) of the Regulatory Flexibility Act (“RFA”); (2) Violation of the Federal Data Quality Act (aka Information Quality Act) (“DQA”/”IQA”) (Pub. L. 106–554, § 515); (3) Violation of Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (“SBREFA”)(Pub. -

Physical Accessibility Guide 2020

Physical Accessibility Guide 2020 Terrain Details for Paths, Walkways and Road Surfaces •Packed and loose gravel, slate, stone and brick. •Grade varies from easy to steep. Travel on the Grounds •Wheelchairs are available at the Museum Store. •Children's strollers and wagons are available at the Museum Store. •Accessible shuttle completes a circuit around the grounds approximately every 15 minutes. Service Accessibility •All services at the Museum Store and Café are fully accessible. •Additional accesible restrooms are located at Railroad Station and Stagecoach Inn. •The Ticonderoga reading room includes an Access and Explore notebook containing images and descriptions of areas of the boat that are not accessible. •Audio and/or video interpretive installations are located in exhibitions in Beach Gallery, the Ticondergoa, the Meeting House, Dorset House, and Variety Unit. •Handheld "i-loview" video magnifiers may be checked out at the Museum Store. The devices magnify up to 32x while also adjusting for brightness and contract, and are best for reading label text and signage. Generously donated by Ai Squared, a Vermont-based accessible technology company. Each exhibit building is listed below, including detailed information on accessibility. Unless otherwise noted, all steps are 8” high or less, and all doorways are at least 32” wide. This symbol indicates first floor accessibility Building Entrance Interior Exit Apothecary Shop Ramp on south side Same as entrance Beach Gallery Level entrance Level exit Beach Lodge Ramp on north side 2 interior -

Oware/Mancala) Bonsai Trees

Carved game boards (Oware/Mancala) Bonsai Trees Raw glass dishware sintered rusted moodust “Luna Cotta” Hewn and carved basalt water features INDEX MMM THEMES: ARTS & CRAFTS (Including Home Furnishings and Performing Arts) FOREWORD: Development of Lunar Arts & Crafts with minimal to zero reliance on imported media and materi- als will be essential to the Pioneers in their eforts to become truly “At Home” on the Moon. Every fron- tier is foreign and hostile until we learn how to express ourselves and meet our needs by creative use of local materials. Arts and Crafts have been an essential “interpretive” medium for peoples of all lands and times. Homes adorned with indigenous Art and Crafts objects will “interpret” the hostile outdoors in a friendly way, resulting in pioneer pride in their surroundings which will be seen as far less hostile and unforgiving as a result. At the same time, these arts and crafts, starting as “cottage industries.” will become an important element in the lunar economy, both for adorning lunar interiors - and exteriors - and as a source of income through sales to tourists, and exports to Earth and elsewhere. Artists love free and cheap materials, and their pursuits will be a part of pioneer recycling eforts. From time immemorial, as humans settled new parts of Africa and then the continents beyond, development of new indigenous arts and crafts have played an important role in adaptation of new en- vironments “as if they were our aboriginal territories.” In all these senses, the Arts & Crafts have played a strong and vital second to the development of new technologies that made adaptation to new frontiers easier. -

NELL Beacon January 2011 FINAL

New England Lighthouse Lovers A Chapter of the American Lighthouse Foundation NELLNELL BeaconBeacon January 2011 NELL’S 2010 YEAR IN REVIEW By Tom Kenworthy, NELL President he weather for the weekend of January 14 Light Foundation (NLLLF). In T and 15, 2010 was sunny with blue skies: his request, Anthony stated perfect for NELL’s annual Lighthouses, Hot NLLLF needed help in Chocolate & You weekend. The Hilton Hotel, scraping, spackling, and Mystic CT was our host hotel. general cleaning. He also stated that the only reason We first visited Morgan Point the work party would be Lighthouse for our 2004 cancelled would be due to LHHC&Y. Having received so inclement weather and/or high many requests to visit/revisit seas. Thankfully, the weather, Morgan Point Lighthouse, it wind, and waves were calm and Anthony made good sense to use that reported that much was accomplished and he is as our starting point for our looking forward to another Project H.O.P.E. at 2010 LHHC&Y. the Ledge Light sometime in the coming year. Leaving Morgan Point, we made the short drive Receiving many requests from our members to to USS Nautilus and the Submarine Force travel to “foreign lands” (outside of New Museum. Here, members decided which to England), Ron and Mike put together a trip to visit first, with it being about a 50-50 split. I the St. Lawrence Seaway. On the weekend of went to the museum first and then toured the May 14-16, we went to lands not traveled to by Nautilus. -

PO Box 957 (Mail & Payments) Woodbury, CT 06798 P

Woodbury Auction LLC 710 Main Street South (Auction Gallery & Pick up) PO Box 957 (Mail & Payments) Woodbury, CT 06798 Phone: 203-266-0323 Fax: 203-266-0707 April Connecticut Fine Estates Auction 4/26/2015 LOT # LOT # 1 Handel Desk Lamp 5 Four Tiffany & Co. Silver Shell Dishes Handel desk lamp, base in copper finish with Four Tiffany & Co. sterling silver shell form interior painted glass shade signed "Handel". 14 dishes, monogrammed. 2 7/8" long, 2 1/2" wide. 1/4" high, 10" wide. Condition: base with Weight: 4.720 OZT. Condition: scratches. repairs, refinished, a few interior edge chips, 200.00 - 300.00 signature rubbed. 500.00 - 700.00 6 Southern Walnut/Yellow Pine Hepplewhite Stand 2 "The Gibson" Style Three Ukulele Southern walnut and yellow pine Hepplewhite "The Gibson" style three ukulele circa stand, with square top and single drawer on 1920-1930. 20 3/4" long, 6 3/8" wide. square tapering legs. 28" high, 17" wide, 16" Condition: age cracks, scratches, soiling, finish deep. Condition: split to top, lacks drawer pull. wear, loss, small edge chips to top. 1,000.00 - 200.00 - 300.00 1,500.00 7 French Marble Art Deco Clock Garniture 3 Platinum & Diamond Wedding Band French marble Art Deco three piece clock Platinum and diamond wedding band containing garniture with enamel dial signed "Charmeux twenty round diamonds weighing 2.02 carats Montereau". 6 1/2" high, 5" wide to 9 3/4" high, total weight. Diamonds are F color, SI1 clarity 12 1/2" wide. Condition: marble chips, not set in a common prong platinum mounting.