The Eastern External Border of the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 September 1992 Judgment

11 SEPTEMBER 1992 JUDGMENT LAND, ISLAh D AND MARITIME FRONTIER DISPUTE (EL SALVADClR/HONDURAS: NICARAGUA intervening) DIFFÉREND FRONTALIER TERRESTRE, INSULAIRE ET MARITIME (EL SALVADOR/HONDURAS; NICARAGUA (intervenant)) 11 SEPTEMBRE 1992 ARRÊT INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE 1992 YEAR 1992 Il September General List No. 75 Il September 1992 CASE CONCERNING THE LAND, ISLAND AND MARITIME FRONTIER DISPUTE (EL SALVADOR/HONDURAS: NICARAGUA inte~ening) Case brought by Special Agreement - Dispute involving six sectors of interna- tional land frontier, legal situation of islands and of maritime spaces inside and outside the Gulfof Fonseca. Land boundaries - Applicability and meaning of principle of uti possidetis juris - Relevance of certain "titles" - Link between disputed sectors and adjoin- ing agreed sectors of boundary - Use of topographical features in boundary-mak- ing - Special Agreement and 1980 General Treaty of Peace between the Parties - Provision in Treaty for account to be taken by Chamber of "evidenceand argu- ments of a legal, historical, human or any other kind, brought before it by the Par- ties and admitted under international law" - Significance to be attributed to Spanish colonial titulos ejidales - Relevance ofpost-independence land titles - Role of effectivités - Demographic considerations and inequalities of natural resources - Considerations of "effective control" of territory - Relationship between titles and effectivités - Critical date. First sector of land boundary - Interpretation of Spanish colonial land titles - Effect of grant by Spanish colonial authorities to community in one province of rights over land situate in another - Whether account may be taken ofproposals or concessions made in negotiations - Whether acquiescence capable of modifying uti possidetis juris situation - Interpretation of colonial documents - Claims based solely on effectivités - Relevance of post-independence Iand titles - Sig- nificance of topographically suitable boundary line agreed ad referendum. -

Warmer Days and Longer Evenings

StowTimes_May09.qxd 27/4/09 15:30 Page 1 STOW TIMES Issue 64 • May 2009 An independent paper delivered to homes & businesses in Stow-on-the-Wold, Broadwell, Adlestrop, Oddington, Bledington, Icomb, Church Westcote, Nether Westcote, Wyck & Little Rissington, Maugersbury, Nether Swell, Lower & Upper Swell, Naunton, Donnington, Condicote, Naunton, Longborough and Temple Guiting Extra copies of Stow Times are generally available in Stow Visitor Information Centre and Stow Library. Warmer days and longer evenings... And there’s LOTS going on Climate Change & energy efficient houses Exhibitions, concerts, fetes & The Prof on the Four Shire Stone festivals, open gardens, glorious walks and Ben Eddols with something for the weekend! record-breaking picnics! Is this the worst best place... Join in! With Local Sport, Clubs and Cinemas – this is your May edition! Photo of bluebell woods kindly provided by James Minter, Chair of the North Cotswolds Digital Camera Club www.ncdcc.co.uk StowTimes_May09.qxd 27/4/09 15:30 Page 2 MAY EVENTS 27th April ~ 2nd May : Fosse Manor Fish Week 4th ~ 30th May : Asparagus Season 10th May : Jazz Sunday Lunch 14th May : Ladies Lunch Club £14.00 per person 28th May : Ladies Lunch Club trip to Abbey Gardens and the Old Bell Hotel in Malmesbury Please telephone for details - booking essential LOOK OUT FOR JUNE EVENTS Website: www.thekingsarmsstow.co.uk Email: [email protected] Telephone: (01451) 830364 AWARD WINNING NASEBY RESTAURANT MAY SPECIAL OFFERS GREAT STAFF AND SERVICE TWO COURSE SET MENU £12 REAL ALES & FINE WINES THREE COURSE SET MENU £15 LOCALS ALWAYS WELCOME! ROOMS FROM £79 B&B BOOK NOW 2 StowTimes_May09.qxd 27/4/09 15:30 Page 3 STOW TIMES From the Editor Inside this edition First, I must say Thank You. -

Continental Shelf (Designation of Areas) Order 2013

Bulletin No. 84 Law of the Sea Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea Office of Legal Affairs Law of the Sea Bulletin No. 84 United Nations New York, 2017 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The texts of treaties and national legislation contained in the Bulletin are reproduced as submitted to the Secretariat. Furthermore, publication in the Bulletin of information concerning developments relating to the law of the sea emanating from actions and decisions taken by States does not imply recognition by the United Nations of the validity of the actions and decisions in question. IF ANY MATERIAL CONTAINED IN THE BULLETIN IS REPRODUCED IN PART OR IN WHOLE, DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SHOULD BE GIVEN. United Nations Publication ISBN 978-92-1-133827-0 Copyright © United Nations, 2017 All rights reserved Printed at the United Nations, New York Contents Page I. UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, of the Agreement relating to the Imple- mentation of Part XI of the Convention and of the Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the Convention relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks 1. -

REPUBLIC of GUYANA V. REPUBLIC of SURINAME

ARBITRATION UNDER ANNEX VII OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA REPUBLIC OF GUYANA v. REPUBLIC OF SURINAME MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF GUYANA VOLUME I 22 FEBRUARY 2005 Memorial of Guyana MEMORIAL OF GUYANA PART I 2 Memorial of Guyana TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I Page CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................1 I. Reasons for the Institution of Proceedings Against Suriname..............................1 II. Guyana’s Approach to the Presentation of the Case.............................................3 III. Structure of the Memorial.....................................................................................3 CHAPTER 2 - GEOGRAPHY AND EARLY HISTORY ...................................................7 I. Geography.............................................................................................................7 II. Early History.......................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 3 - EFFORTS OF THE COLONIAL POWERS TO SETTLE THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN BRITISH GUIANA AND SURINAME: 1929 TO 1966........13 I. The Fixing of the Northern Land Boundary Terminus between British Guiana and Suriname: 1936................................................................................14 II. The First Attempt To Fix a Maritime Boundary in the Territorial Sea: 1936 ....18 III. The Draft Treaty To Settle the Entire Boundary: 1939 ......................................20 IV. Unsuccessful Post-World -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Fa<m !CHIOO·C IJin .:~n United States Department of the Interior National Park Service .. "')" National Register of Historic Places - !~ ......=· Multiple Property Documentation Form N.!.TIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documentmg multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts See instructions in Guidelines tor Completmg Nst1onsl Reg1ster Forms (National Reg1ster Bulletin 16). Complete each 1tem by markmg "x" in the appropnate box or by entenng the requested informat1on. For additional space use contmuat1on sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entnes. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Boundary Markers of the original District of Columbia B. Associated Historic Contexts Establishment of the Original Boundaries of the District of Columbia C. Geographical Data The boundary markers of the original District of Columbia located in the Commonwealth of Virginia are within the jurisdictions of the counties of Arlington and Fairfax and the cities of Alexandria and Falls Church. They are spaced at more or less regular intervals of one mile along a line drawn between the UTM coordinates 18132276014295280 and 18131157014306900 and between the UTM coordinates 18131157014306900 and 18I315080j4310370. _See continuation sheet 0. Certification As the designated authority under the National Hrstonc Preservatron Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that th1s documentation form meets the National Regrster documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submiss1on meets the procedural and profess1onal requir ents set fonh m 6 FA Pan 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. /7 ~ lf7a Date r, Virgi~ia De~artment of Historic ReEources State or Federal agency ana bureau I, hereby, certify that th1s mulliple property documentation form has been approved by the Nat1onal Reg1ster as a bas1s for e luating related properties tcr lis!lng .... -

SEPARATE OPINION of JUDGE TORRES BERNARDEZ 1 Have

SEPARATE OPINION OF JUDGE TORRES BERNARDEZ 1 have voted for the operative part of the Judgment, except for sub- paragraph 1, subparagraph 2 (i) and subparagraph 5 of operative para- graph 43 1 and subparagraph 2 of operative paragraph 432. Except with respect to the attribution of sovereignty over the island of Meanguerita, my negative votes concern questions relating to the interpretation of Article 2, paragraph 2, of the Special Agreement. The considerations and observations included in the present opinion have a threefold purpose. They intend to convey the essentials of my posi- tion on: (1) questions with respect to which, to my regret, 1 was unable to join the majority vote; (2) questions on which 1 have some reservations notwithstanding my positive vote on the decision concerned as a whole; and (3) main developments in the reasoning which 1 do not share com- pletely or which would have deserved, in my opinion, further elaboration. After a brief introduction concerning the case as a whole, my considera- tions and observations are presented under the main headings of the three major aspects of the case, namely the "land boundary dispute", the "island dispute" and the "maritime dispute". The table of contents thus presents the following synopsis : Paragraphs INTRODUCTION.THE CASE 1-7 1. THELAND BOUNDARY DISPUTE 8-55 A. General questions 8-37 (a) The 1821 utipossidetisjurisprinciple as applicable law 8-15 (b) The utipossidetis juris principle and the rule of evidence in Article 26 of the General Treaty of Peace 16-20 (c) The utipossidetisjuris principle and the effectivités 2 1-27 (d) The uti possidetis juris principle and the rirulos ejidales invoked by the Parties 28-37 B. -

Combined CCI Copy.Cwk

T-M TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: COMPOSITE CATEGORIES CLASSIFICATION & INDEX Brian Clearman Mount Angel Abbey 2012 Saint Benedict, Oregon TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS DATABASE: COMPOSITE CATEGORIES CLASSIFICATION & INDEX TRANSPORTATION-MARKINGS: A STUDY IN COMMUNICATION MONOGRAPH SERIES Alternate Series Title: An Inter-modal Study of Safety Aids Alternate T-M Titles: Transport [ation] Mark [ings]/Transport Marks/Waymarks/ Transportation Control Devices T-M Foundations, 5the edition, 2008 (Part A, Volume I, First Studies in T-M (2nd ed., 1991; 3rd ed., 1999, 4th ed., 2005) A First Study in T-M: The US, 2nd ed., 1992 (Part B, Vol. I) International Marine Aids to Navigation, 3rd edition, 2010 (Parts C & D, Vol. I) (2nd ed., 1988) [Unified lst Edition of Parts A-D, 1981, University of America Press] International Traffic Control Devices, 2nd ed., 2004 (Part E, Vol. II, Further Studies in T-M) (lst ed., 1984) International Railway Signals, 1991 (Part F, Vol. II). International Aero Navigation Aids, 1994 (Part G, Vol. II). T-M General Classification, 3rd edition, 2010 (Part II, Vol. II) (2nd ed., 2003; 3rd ed., 1995). Transportation-Markings Database: Marine, 2nd ed., 2007 (Part Ii, Vol. III, Additional Studies in T-M), (1st ed., 1997) TCD, 2nd. ed., 2008 (Part Iii, Vol. III), (lst ed., 1998) Railway, 2nd ed., 2009 (Part Iiii), (lst ed., 2000) Aero, 2nd ed., 2009 (Part Iiv) (lst ed., 2001) Composite Categories Classification & Index, 2nd ed., 2012 (Part Iv, Vol. III) (lst ed., 2006) Transportation-Markings: A Historical Survey, 1750-2000, 2002 (Part J, Vol. IV, Final Studies in T-M) Transportation-Markings: An Integrative Systems Perspective: Communication, Information, Semiotics, 2011 (Part K, Vol. -

Norwegian University of Life Sciences/Connor J

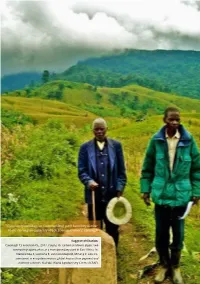

Community members on contested land, park boundary marker Photo: Norwegian University of Life Sciences/Connor J. Cavanagh Suggested Citation: Cavanagh CJ, Freeman OE. 2017. Paying for carbon at Mount Elgon: two contrasting approaches at a transboundary park in East Africa. In: Namirembe S, Leimona B, van Noordwijk M, Minang P, eds. Co- investment in ecosystem services: global lessons from payment and incentive schemes. Nairobi: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). Chapter 28 | 1 CHAPTER 28 Paying for carbon at Mount Elgon: two contrasting approaches at a transboundary park in East Africa Connor J Cavanagh and Olivia E Freeman Highlights • We compare and contrast delivery of community benefits under two approaches to PES. • UWA-FACE provided employment; MERECP negotiated CRMAs and revolving funds. • By 2004 more than 44% of UWA-FACE forest units were compromised by encroachment. • MERECP’s community revolving funds have been met with mixed success. • Both market and fund-based PES approaches require locally-relevant benefit sharing. 28.1 Introduction Across East Africa and beyond, resource management authorities have begun to experiment with various payment for ecosystem service (PES) mechanisms for strengthening the governance of protected areas. Perhaps the most widespread of these are payment for carbon sequestration and avoided deforestation initiatives, in which finances are disbursed to forest users or managers via either trust funds or voluntary markets. Though often identified as a ‘triple win’ solution for biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, and socioeconomic development, such potential benefits of course will only be realized if these initiatives are sustainably designed, effectively governed, and attentive to local perceptions of social and environmental justice. -

Landmarks and Monuments of Interest to Surveyors

Landmarks and Monuments of Interest to Surveyors 4 Hours PDH Academy PO Box 449 Pewaukee, WI 53072 (888) 564-9098 www.pdhcademy.com Landmarks and Monuments of Interest to Surveyors Final Exam 1. The Roman poet Ovid penned a lengthy tribute to this god responsible for the protection of boundary markers: a. Romulus b. Terminus c. Orion d. Titus 2. Which United States President executed the Louisiana Purchase, virtually doubling the area of the nation? a. James Monroe b. James Madison c. John Quincy Adams d. Thomas Jefferson 3. The Zero Milestone in Washington, D.C. was erected for what purpose? a. To serve as an elevation benchmark b. To mark the center of the city c. To serve as a reference point from which to measure and name the nation’s roads d. To mark the midway point on the National Mall 4. The first and oldest monument erected on the U.S. – Canada border is in Maine and is called: a. Monument One b. The Initial Monument c. The Primary Point d. The First Monument 5. The northernmost point in the contiguous 48 states is found in which state? a. Minnesota b. Maine c. Michigan d. Washington 6. The highest point of elevation in the United States is located in which national park? a. Rocky Mountain b. Yosemite c. Denali d. Sequoia 7. What valuable substance was discovered in the Sierra Nevada Range in 1848? a. Copper b. Silver c. Coal d. Gold 8. This last natural landmark encountered by westbound travelers on the Santa Fe Trail is located in New Mexico and is named for its resemblance to a common item: a. -

Bagrow–Bundesamt

on a Dutch globe in Moscow, was published in 1956. Twenty-nine of these works were on specifi c Russian topics, his abiding lifelong interest. Four more works were published posthumously, including A History of the Cartography of Russia Up to 1600 and A History of B Russian Cartography Up to 1800. Bagrow traveled widely throughout his lifetime. When Bagrow, Leo. Born in 1881 in Siberia, Leo Bagrow living in Europe he was agent for various commercial (Lev Semenovich Bagrov) spent most of his professional and fi nancial fi rms. During his leisure time, he was able career in Berlin and Stockholm, where he founded and to discover, report, and sometimes purchase many rare edited the prestigious journal Imago Mundi, wrote over Russian maps for his private collections. His abrupt seventy scholarly publications on the history of cartog- departures from St. Petersburg and later from Berlin raphy, and discovered and collected many rare maps. meant that he lost many of these treasures. To his dis- Bagrow attended preparatory school in Siberia before credit, some of his Russian items were acquired illegally. graduating from the Archaeological Institute in St. Pe- Despite this, his work and contributions were known tersburg. Entering the Russian Imperial Navy, he was and studied in the Soviet Union. But because he never trained as a navigator. Subsequent service as an offi cer returned there, some of his later work may have suf- in the Hydrographic Department took him to the four fered from unfamiliarity with archival collections and corners of Russia. contemporary Soviet research. In November 1918, Bagrow and his wife Olga emi- His last trip, an unfortunate visit to Ethiopia in the grated to Berlin. -

Preliminary Inventories

PRELIMINARY INVENTORIES Number 170 RECORDS RELATING TO INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1968 PRELIMINARY INVENTORY OF THE RECORDS RELATING TO INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES (RECORD GROUP 76) Compiled by Daniel T. Goggin The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1968 National Archives Publication No. 69-2 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A68-7772 GSA through the National Archives and Records Service is responsible for administering the permanent noncurrent records of the Federal Government. These archival hold ings, now amounting to about 900,000 cubic feet, date from the days of the Continental Congresses; they include the basic records of the three branches of our Government- Congress, the courts, and the executive departments and independent agencies. The Presidential Libraries--Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower--contain the papers of those Presidents and many of their associates in office. Among our holdings are many hallowed documents relating to great events of our Nation's history, preserved and ven erated as symbols to stimulate a worthy patriotism in all of us. But most of the records are less dramatic, kept because of their continuing practical utility for the ordinary proc esses of government, for the protection of private rights, and for the research use of students and scholars. To facilitate the use of the records and to describe their nature and content, our archivists prepare various kinds of finding aids. The present work is one such publication. We believe that it will prove valuable to anyone who wishes to use the records it describes. -

Relsymbjancz

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a chapter published in De-Bordering, Re-Bordering and Symbols on the European Boundaries. Citation for the original published chapter: Lundén, T. (2011) Religious Symbols as Boundary Markers in Physical Landscapes: An Aspect of Human Geography. In: Jaroslaw Jańczak (ed.), De-Bordering, Re-Bordering and Symbols on the European Boundaries (pp. 9-19). Berlin: Logos Verlag Berlin Thematicon N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published chapter. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-21060 9 Religious Symbols as Boundary Markers in Physical Landscapes. An Aspect of Human Geography Thomas Lundén Introduction With the changes occurring in the spatial extent and content of authoritative rule in Europe from the late 1980’s to the end of hostilities in the Balkans, two opposite pro- cesses have taken place; de-bordering and re-bordering. De-bordering is a process whereby contained territories are opened towards sur- rounding areas. In Western Europe, i.e. the 15 first members of the European Union plus Norway and others, this de-bordering process started with simplified rules for crossing state borders, and ended with, in principle, the withdrawal of border pass- port controls. In Central and Eastern Europe, i.e. the former non-Soviet members of the Warsaw Pact plus the former Soviet Baltic Republics, the de-bordering process started with the amalgamation of the two German states in 1990 and the change from a state territorial authoritarian system into a market economy. But not until the membership of the European Union and the successive entrance into the Schengen regime did these states enter a truly de-bordering phase.