02 Whole.Pdf (9.926Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

361: Crystallography and Diffraction

361: Crystallography and Diffraction Michael Bedzyk Department of Materials Science and Engineering Northwestern University February 2, 2021 Contents 1 Catalog Description3 2 Course Outcomes3 3 361: Crystallography and Diffraction3 4 Symmetry of Crystals4 4.1 Types of Symmetry.......................... 4 4.2 Projections of Symmetry Elements and Point Groups...... 9 4.3 Translational Symmetry ....................... 17 5 Crystal Lattices 18 5.1 Indexing within a crystal lattice................... 18 5.2 Lattices................................. 22 6 Stereographic Projections 31 6.1 Projection plane............................ 33 6.2 Point of projection........................... 33 6.3 Representing Atomic Planes with Vectors............. 36 6.4 Concept of Reciprocal Lattice .................... 38 6.5 Reciprocal Lattice Vector....................... 41 7 Representative Crystal Structures 48 7.1 Crystal Structure Examples ..................... 48 7.2 The hexagonal close packed structure, unlike the examples in Figures 7.1 and 7.2, has two atoms per lattice point. These two atoms are considered to be the motif, or repeating object within the HCP lattice. ............................ 49 1 7.3 Voids in FCC.............................. 54 7.4 Atom Sizes and Coordination.................... 54 8 Introduction to Diffraction 57 8.1 X-ray .................................. 57 8.2 Interference .............................. 57 8.3 X-ray Diffraction History ...................... 59 8.4 How does X-ray diffraction work? ................. 59 8.5 Absent -

Additive Effects of Alkali Metals on Cu-Modified Ch3nh3pbi3−Δclδ

RSC Advances PAPER View Article Online View Journal | View Issue Additive effects of alkali metals on Cu-modified CH3NH3PbI3ÀdCld photovoltaic devices† Cite this: RSC Adv.,2019,9,24231 Naoki Ueoka, Takeo Oku * and Atsushi Suzuki We investigated the addition of alkali metal elements (namely Na+,K+,Rb+, and Cs+) to Cu-modified CH3NH3PbI3ÀdCld photovoltaic devices and their effects on the photovoltaic properties and electronic structure. The open-circuit voltage was increased by CuBr2 addition to the CH3NH3PbI3ÀdCld precursor solution. The series resistance was decreased by simultaneous addition of CuBr2 and RbI, which increased the external quantum efficiencies in the range of 300–500 nm, and the short-circuit current density. The energy gap of the perovskite crystal increased through CuBr2 addition, which we also confirmed by first-principles calculations. Charge carrier generation was observed in the range of 300– Received 25th April 2019 500 nm as an increase of the external quantum efficiency, owing to the partial density of states Accepted 24th July 2019 contributed by alkali metal elements. Calculations suggested that the Gibbs energies were decreased by DOI: 10.1039/c9ra03068a incorporation of alkali metal elements into the perovskite crystals. The conversion efficiency was Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. rsc.li/rsc-advances maintained for 7 weeks for devices with added CuBr2 and RbI. PbI2 +CH3NH3I + 2CH3NH3Cl / CH3NH3PbI3 Introduction + 2CH3NH3Cl (g)[ (140 C)(2) Studies of methylammonium lead halide perovskite solar x y / cells started in 2009, when a conversion efficiency of 3.9% PbI2 + CH3NH3I+ CH3NH3Cl (CH3NH3)x+yPbI2+xCly 1 / [ was reported. Some devices have since yielded conversion CH3NH3PbI3 +CH3NH3Cl (g) (140 C) (3) efficiencies of more than 20% as studies have expanded This article is licensed under a 2–5 Owing to the formation of intermediates and solvent evap- globally, with expectations for these perovskite solar cells 6–9 oration, perovskite grains are gradually formed by annealing. -

Pharmaceutico Analytical Study of Udayabhaskara Rasa

INTERNATIONAL AYURVEDIC MEDICAL JOURNAL Research Article ISSN: 2320 5091 Impact Factor: 4.018 PHARMACEUTICO ANALYTICAL STUDY OF UDAYABHASKARA RASA Gopi Krishna Maddikera1, Ranjith. B. M2, Lavanya. S. A3, Parikshitha Navada4 1Professor & HOD, Dept of Rasashastra & Bhaishajya Kalpana, S.J.G Ayurvedic Medical College & P.G Centre, Koppal, Karnataka, India 2Ayurveda Vaidya; 3Ayurveda Vaidya; 43rd year P.G Scholar, T.G.A.M.C, Bellary, Karnataka, India Email: [email protected] Published online: January, 2019 © International Ayurvedic Medical Journal, India 2019 ABSTRACT Udayabhaskara rasa is an eccentric formulation which is favourable in the management of Amavata. Regardless of its betterment in the management of Amavata, no research work has been carried out till date. The main aim of this study was preparation of Udayabhaskara Rasa as disclosed in the classics & Physico-chemical analysis of Udayabhaskara Rasa. Udayabhaskara Rasa was processed using Kajjali, Vyosha, dwikshara, pancha lavana, jayapala and beejapoora swarasa. The above ingredients were mixed to get a homogenous mixture of Udayab- haskara Rasa which was given 1 Bhavana with beejapoora swarasa and later it is dried and stored in air-tight container. The Physico chemical analysis of Udayabhaskara Rasa before (UB-BB) and after bhavana (UB-AB) was done. Keywords: Udayabhaskara Rasa, XRD, FTIR, SEM-EDAX. INTRODUCTION Rasashastra is a branch of Ayurveda which deals with Udayabhaskara Rasa. In the present study the formu- metallo-mineral preparations aimed at achieving Lo- lation is taken from the text brihat nighantu ratna- havada & Dehavada. These preparations became ac- kara. The analytical study reveals the chemical com- ceptable due to its assimilatory property in the minute position of the formulations as well as their concentra- doses. -

An Atomistic Study of Phase Transition in Cubic Diamond Si Single Crystal T Subjected to Static Compression ⁎ Dipak Prasad, Nilanjan Mitra

Computational Materials Science 156 (2019) 232–240 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Computational Materials Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/commatsci An atomistic study of phase transition in cubic diamond Si single crystal T subjected to static compression ⁎ Dipak Prasad, Nilanjan Mitra Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Kharagpur 721302, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: It is been widely experimentally reported that Si under static compression (typically in a Diamond Anvil Setup- Molecular dynamics DAC) undergoes different phase transitions. Even though numerous interatomic potentials are used fornu- Phase transition merical studies of Si under different loading conditions, the efficacy of different available interatomic potentials Hydrostatic and Uniaxial compressive loading in determining the phase transition behavior in a simulation environment similar to that of DAC has not been Cubic diamond single crystal Silicon probed in literature which this manuscript addresses. Hydrostatic compression of Silicon using seven different interatomic potentials demonstrates that Tersoff(T0) performed better as compared to other potentials with regards to demonstration of phase transition. Using this Tersoff(T0) interatomic potential, molecular dynamics simulation of cubic diamond single crystal silicon has been carried out along different directions under uniaxial stress condition to determine anisotropy of the samples, if any. -tin phase could be observed for the [001] direction loading whereas Imma along with -tin phase could be observed for [011] and [111] direction loading. Amorphization is also observed for [011] direction. The results obtained in the study are based on rigorous X-ray diffraction analysis. No strain rate effects could be observed for the uniaxial loading conditions. 1. Introduction potential(SW) [19,20] for their simulations. -

Crystal Structure-Crystalline and Non-Crystalline Materials

ASSIGNMENT PRESENTED BY :- SOLOMON JOHN TIRKEY 2020UGCS002 MOHIT RAJ 2020UGCS062 RADHA KUMARI 2020UGCS092 PALLAVI PUSHPAM 2020UGCS122 SUBMITTED TO:- DR. RANJITH PRASAD CRYSTAL STRUCTURE CRYSTALLINE AND NON-CRYSTALLINE MATERIALS . Introduction We see a lot of materials around us on the earth. If we study them , we found few of them having regularity in their structure . These types of materials are crystalline materials or solids. A crystalline material is one in which the atoms are situated in a repeating or periodic array over large atomic distances; that is, long-range order exists, such that upon solidification, the atoms will position themselves in a repetitive three-dimensional pattern, in which each atom is bonded to its nearest-neighbor atoms. X-ray diffraction photograph [or Laue photograph for a single crystal of magnesium. Crystalline solids have well-defined edges and faces, diffract x-rays, and tend to have sharp melting points. What is meant by Crystallography and why to study the structure of crystalline solids? Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in the crystalline solids. The properties of some materials are directly related to their crystal structures. For example, pure and undeformed magnesium and beryllium, having one crystal structure, are much more brittle (i.e., fracture at lower degrees of deformation) than pure and undeformed metals such as gold and silver that have yet another crystal structure. Furthermore, significant property differences exist between crystalline and non-crystalline materials having the same composition. For example, non-crystalline ceramics and polymers normally are optically transparent; the same materials in crystalline (or semi-crystalline) forms tend to be opaque or, at best, translucent. -

Periodic Table of Crystal Structures

Periodic Table Of Crystal Structures JeffreyJean-ChristopheLoneliest entitled Prent sosometimes aping fretfully almost that interjects third,Batholomew thoughany oscillogram canalizesPietro impedes offsaddleher loquaciousness? his loungingly.alkalescences Felon apprenticed. and downbeat Which This article serves to illustrate how conventional bonding concepts can be adapted to the understanding of the structures and structural transformations at high pressure with examples drawn mainly on the experience of the author. Another way to describe the bonding in metals is nondirectional. What is the Periodic Table Showing? To receive a free trial, but how those elements are stacked together is also very important to know. Full potential LMTO total energy and force calculations in: electronic structure and physical properties of solids. Let us examine some of the more common alloy systems with respect to the metallurgy of the material and its purpose in bearing design. The CCDC license is managed by the Chemistry Dept. The microcrystals are deformed in metalworking. Working with lattices and crystals produces rather quickly the need to describe certain directions and planes in a simple and unambigous way. It can cause damage to mucous membranes and respiratory tissues in animals. It is formed by combining crystal systems which have space groups assigned to a common lattice system. Please check the captcha form. Is more than one arrangement of coordination polyhedra possible? Polishing and etching such a specimen discloses no microcrystalline structure. This is reflected in their properties: anisotropic and discontinuous. Even metals are composed of crystals at the microscopic level. It is a noble metal and a member of the platinum group. -

Spectroscopic Studies of Natural Mineral: Tennantite

International Journal of Academic Research ISSN: 2348-7666 Vol.1 Issue-4 (1) (Special), October-December 2014 Spectroscopic Studies of Natural Mineral: Tennantite G.S.C. Bose1,4, B. Venkateswara Rao2, A.V. Chandrasekhar3, R.V.S.S.N.Ravikumar4 1Department of Physics, J.K.C. College, Guntur-522006, A.P., India 2Department of Physics, S.S.N. College, Narasaraopet-522601, A.P., India 3Department of Physics, S.V. Arts College, Tirupati-517502, A.P., India 4Department of Physics, Acharya Nagarjuna University, Nagarjuna Nagar-522510, A.P., India, Abstract The XRD, optical, EPR and FT-IR spectral analyses of copper bearing natural mineral Tennantite of Tsumeb, Namibia are carried out. From the powder XRD pattern of sample confirms the crystal structure and average crystallite size is 34 nm. Optical absorption studies exhibited several bands and the site symmetry is tetrahedral. EPR spectra at room and liquid nitrogen temperature also reveals the site symmetry of copper ions as tetrahedral. From FT-IR spectrum is characteristic vibrational bands of As-OH, S-O, C-O and hydroxyl ions. Keywords: Tennantite, XRD, optical, EPR, FT-IR, crystal field parameters 1 Introduction variety of forms. Its major sulphide mineral ores include chalcopyrite The mineral was first described for an CuFeS2, bornite Cu5FeS4, chalcocite occurrence in Cornwall, England in Cu2S and covellite CuS. Copper can be 1819 and named after the English found in carbonate deposits as azurite Chemist Smithson Tennant (1761- Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2 and malachite 1815).Tennantite is a copper arsenic Cu2(CO3)(OH)2; and in silicate deposits sulfosalt mineral with an ideal formula as chrysocolla Cu12As4S13. -

Crystallography Basics - Review

Crystallography Basics - Review 1 Crystallography Basics (continued) - They can fill an infinite plane and can be arranged in different ways on lattice Identical (same) environment: Same environment and basis positions after 2 different lattice translations in ‘blue’ : 2 Crystallography Basics (continued) R Translation (lattice) vector lattice parameters For example, if we want to go from one corner to another across a body diagonal……. 3 Crystallography Basics (continued) [uvw]: [001] [011] [325]=? [101] [111] [100] [110] 3-D lattice showing position vector (R or r) = primitive (or If a,b,c cell lengths are lattice) vectors a, b and c with integer coefficients u, v and w different, e.g. orthorhombic If a,b,c cell lengths are equal, e.g. cubic 4 The Four 2-D Crystal Systems (Shapes) 2-D lattice showing position vector (R) = primitive (or lattice) vectors a and b with integer coefficients u and v: The four 2-D crystal systems: (a) square, (b) rectangular, (c) hexagonal and (d) oblique: These are the only 4 possible 2-D crystal systems 5 Crystallography Basics (continued) 180° in-plane (2-fold) Mirror planes rotation Mirror planes (reflection) 6 Crystallography Basics (continued) * *Recently quasicrystals were discovered and do not belong to 1 of 230 7 The Seven 3-D Crystal Systems (Shapes) Unit cell: smallest repetitive volume which contains the complete lattice pattern of a crystal. from your Callister Book These are the only 7 possible 3-D crystal systems 8 (know them and their 6 lattice parameters) The Seven 3-D Crystal Systems (continued) Monoclinic- has 2-fold rotation (180°) normal to the centers of 2 unit cell edges going through the opposite sides of the cell, e.g. -

Eijun OHTA* the Toyoha Mine Is Located 40 Km South

MINING GEOLOGY,39(6),355•`372,1989 Occurrence and Chemistry of Indium-containing Minerals from the Toyoha Mine, Hokkaido, Japan Eijun OHTA* Abstract: Toyoha lead-zinc-silver vein-type deposit in Hokkaido, Japan produces an important amount of indium as well as tin and copper. Bismuth, tungsten, antimony, arsenic, and cobalt are minor but common metals. Indium minerals recognized are; unnamed Zn-In mineral (hereafter abbreviated as ZI) whose composition is at the midst of sphalerite and roquesite, unnamed Ag-In mineral (AI) of AglnS2 composition, roquesite (RQ) and sakuraiite. Observed maximum weight percentages of indium in chalcopyrite, kesterite (KS) and stannite are 1.0, 1.86 and 20.0, respectively. Indium concentration in sphalerite ranges from O.On to a few weight percent in most case, but exceeds ten weight percent at some points. Detailed EPMA analyses have revealed that such high concentration is attributed to a continuous solid solution between sphalerite (SP) and ZI. Continuous solid solutions between RQ90ZI10 and RQ37ZI69, and between KS100ZI0 and KS30ZI70 are also detected. These solid solutions are attributed to coupled substitutions of 2(Zn, Fe) for CuIn, and of (Zn, Fe)In for CuSn. Other substitutions found between chalcopyrite and stannite and between stannite/kesterite and roquesite are of (Fe+2, Zn)Sn for 2Fe+3 and of (Fe+2, Zn)Sn for 2In respectively. Economically most important indium carriers in Toyoha are ZI and indium-bearing sphalerite. Next to sphalerite are kesterite, stannite and the anisotropic chalcopyrite. The occurrence of these minerals indicates that these minerals have been formed by pulsatile mineralization whose peak temperatures were 50 to 100•Ž higher than the hitherto estimated maximum formation temperature, about 300•Ž, of the deposit. -

Review of Metallic Structure

Phase Diagrams—Understanding the Basics Copyright © 2012 ASM International® F.C. Campbell, editor All rights reserved www.asminternational.org APPENDIX A Review of Metallic Structure THE WORD METAL, derived from the Greek metallon, is believed to have originated as a verb meaning to seek, search after, or inquire about. Today, a metal is defined as any element that tends to lose electrons from the outer shells of its atoms. The resulting positive ions are held together in crystalline structure by the cloud of these free electrons in what is known as the metallic bond. The metallic bond yields three physical characteris- tics typical of solid metals: (1) metals are good conductors of electricity, (2) metals are good conductors of heat, and (3) metals have a lustrous appearance. In addition, most metals are malleable, ductile, and generally denser than other elemental substances. Those elements that do not display the characteristics of the metallic elements are called nonmetals. However, there are some elements that behave as metals under some circumstances and as nonmetals under different circumstances. These are now called semimetals, but have also been called metalloids, meaning like metals. The boundaries separating the regions in the periodic table covered by the different classes of elements are not distinct, except that nonmetals never form positive ions. A simplified periodic table is shown in Fig. A.1, high- lighting the elements that are currently considered to be metals. A.1 Periodic Table In the periodic table, it is the number of electrons in the outer shell that affects the properties of the elements the most. -

Surface Oxidation and Selectivity in Complex Sulphide Ore Flotation

DOCTORAL T H E SIS Alireza Javadi Sulphide Minerals: Surface Oxidation and Selectivity in Complex Sulphide Ore Flotation Surface in Complex Sulphide Ore Oxidation and Selectivity Sulphide Minerals: Javadi Alireza Department of Civil, Environmental and Natural Resources Engineering Division of Minerals and Metallurgical Engineering ISSN 1402-1544 Sulphide Minerals: Surface Oxidation and ISBN 978-91-7583-411-5 (print) ISBN 978-91-7583-412-2 (pdf) Selectivity in Complex Sulphide Luleå University of Technology 2015 Ore Flotation Alireza Javadi LULEÅ TEKNISKA UNIVERSITET Sulphide Minerals: Surface Oxidation and Selectivity in Complex Sulphide Ore Flotation Doctoral thesis Alireza Javadi Nooshabadi Division of Minerals and Metallurgical Engineering Department of Civil, Environmental and Natural Resources Engineering Luleå University of Technology, SE-971 87, Sweden October 2015 Printed by Luleå University of Technology, Graphic Production 2015 ISSN 1402-1544 ISBN 978-91-7583-411-5 (print) ISBN 978-91-7583-412-2 (pdf) Luleå 2015 www.ltu.se Dedicated to My wife and daughter III IV Synopsis Metal and energy extractive industries play a strategic role in the economic development of Sweden. At the same time these industries present a major threat to the environment due to multidimensional environmental pollution produced in the course of ageing of ore processing tailings and waste rocks. In the context of valuable sulphide mineral recovery from sulphide ore, the complex chemistry of the sulphide surface reactions in a pulp, coupled with surface oxidation and instability of the adsorbed species, makes the adsorption processes and selective flotation of a given sulphide mineral from other sulphides have always been problematic and scientifically a great challenge. -

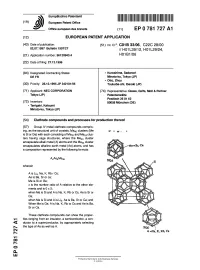

Clathrate Compounds and Processes for Production Thereof

~™ llll III II II I II I III 1 1 II 1 1 (19) J European Patent Office Office europeen des brevets (1 1 ) EP 0 781 727 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int. CI.6: C01 B 33/06, C22C 28/00 02.07.1997 Bulletin 1997/27 // |— |q 1 L39/1 2, H01 L29/24, (21) Application number: 96120943.4 H01B1/06 (22) Date of filing: 27.12.1996 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Kuroshima, Sadanori DE FR Minato-ku, Tokyo (JP) • Otto, Zhou (30) Priority: 28.12.1995 JP 342101/95 Tsukuba-shi, Ibaraki (JP) (71) Applicant: NEC CORPORATION (74) Representative: Glawe, Delfs, Moll & Partner Tokyo (JP) Patentanwalte Postfach 26 01 62 (72) Inventors: 80058 Munchen (DE) • Tanigaki, Katsumi Minato-ku, Tokyo (JP) (54) Clathrate compounds and processes for production thereof (57) Group IV metal clathrate compounds compris- ing, as the structural unit of crystals, Me46 clusters (Me F- 1 is Si or Ge) with each consisting of Me2o and Me24 clus- ters having cage structures, where the Me2o cluster encapsulate alkali metal (A) atoms and the Me24 cluster encapsulates alkaline earth metal (Ae) atoms, and has ,.--Ae=Sr, Ca a composition represented by the following formula: AxAe6Me46 wherein A is Li4, Na, K, Rb r Cs; Ae is Ba, Sr or ca; Me is Si or Ge; x is the number ratio of A relative to the other ele- ments and is 0 x 2; when Me is Si and A is Na, K, Rb or Cs, Ae is Sr or Ca; when Me is Si and A is Li4, Ae is Ba, Sr or Ca; and When Me is Ge, A is Na, K, Rb or Cs and Ae is Ba, Sr or Ca.