Amending the Global Discourse on Narcotic Drugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P40 Layout 1

In Damascus, a ‘Cinema Paradiso’ struggles38 to stay open SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2013 VENICE: Director Alexandros Avranas (C), actor Themis Panou and actress Eleni Roussinou pose on the red carpet as they arrive for the award ceremony of the 70th Venice Film Festival yesterday at Venice Lido. —AFP ritics have tipped movies from Britain, Japan and the inative tale of life in Japan between the two World Wars would A total of 20 films are competing at the festival, including not have the patience to appreciate my slowness,” he told jour- United States to win Venice’s Golden Lion prize this year, be his last feature. James Franco’s necrophilia flick “Child of God”, the tale of a social nalists. Some critics suggested that, with the US mulling inter- Cdue to be announced at the world’s oldest film festival “In the past, I have said many times I would quit. This time, it’s outcast whose loneliness drives him to live in a cave and murder vening in the Middle East again, the jury might give the award to yesterday. British director Stephen Frears provoked a hugely for real,” the 72-year-old said in Tokyo. He had become too old women to have sex with their bodies. Errol Morris’s “The Unknown Known”, an interview with former enthusiastic response with his charming tragi-comedy for the kind of craftsmanship and physical work required for US actor Scott Haze-who isolated himself for three months US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld. “Philomena”, the true tale of a mother’s search for her son after major commercial projects, he added. -

A Main Document V202

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: TELEVISION NEWS AND THE STATE IN LEBANON Jad P. Melki, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Professor Susan D. Moeller College of Journalism This dissertation studies the relationship between television news and the state in Lebanon. It utilizes and reworks New Institutionalism theory by adding aspects of Mitchell’s state effect and other concepts devised from Carey and Foucault. The study starts with a macro-level analysis outlining the major cultural, economic and political factors that influenced the evolution of television news in that country. It then moves to a mezzo-level analysis of the institutional arrangements, routines and practices that dominated the news production process. Finally, it zooms in to a micro-level analysis of the final product of Lebanese broadcast news, focusing on the newscast, its rundown and scripts and the smaller elements that make up the television news story. The study concludes that the highly fragmented Lebanese society generated a similarly fragmented and deeply divided political/economic elite, which used its resources and access to the news media to solidify its status and, by doing so, recreated and confirmed the politico-sectarian divide in this country. In this vicious cycle, the institutionalized and instrumentalized television news played the role of mediator between the elites and their fragmented constituents, and simultaneously bolstered the political and economic power of the former while keeping the latter tightly held in their grip. The hard work and values of the individual journalist were systematically channeled through this powerful institutional mechanism and redirected to serve the top of the hierarchy. -

P40 Layout 1

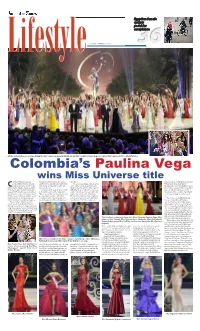

Egyptian female cyclists pedal for acceptance TUESDAY, JANUARY 27, 2015 36 All the contestants pose on stage during the Miss Universe pageant in Miami. (Inset) Miss Colombia Paulina Vega is crowned Miss Universe 2014.— AP/AFP photos Colombia’s Paulina Vega wins Miss Universe title olombia’s Paulina Vega was Venezuelan Gabriela Isler. She edged the map. Cuban soap opera star William Levy and crowned Miss Universe Sunday, out first runner-up, Nia Sanchez from the “We are persevering people, despite Philippine boxing great Manny Cbeating out contenders from the United States, hugging her as the win all the obstacles, we keep fighting for Pacquiao. The event is actually the 2014 United States, Ukraine, Jamaica and The was announced. what we want to achieve. After years of Miss Universe pageant. The competition Netherlands at the world’s top beauty London-born Vega dedicated her title difficulty, we are leading in several areas was scheduled to take place between pageant in Florida. The 22-year-old mod- to Colombia and to all her supporters. on the world stage,” she said earlier dur- the Golden Globes and the Super Bowl el and business student triumphed over “We are proud, this is a triumph, not only ing the question round. Colombian to try to get a bigger television audi- 87 other women from around the world, personal, but for all those 47 million President Juan Manuel Santos applaud- ence. and is only the second beauty queen Colombians who were dreaming with ed her, praising the brown-haired beau- The contest, owned by billionaire from Colombia to take home the prize. -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

Issue Nº 1 | Spring 2016

Steering towards a brighter future. Empowering our students to take the helm. A CIVIC MISSION WITH GLOBAL RECOGNITION As a leading regional academic institution, the Lebanese American University strives to shape a generation of ethically-minded individuals committed to social change and conflict resolution. Through its holistic approach to education and civic engagement, LAU nurtures well-rounded discerning individuals respectful of diversity, tolerance and the needs of their community. The entire LAU community is involved in countless philanthropic initiatives from volunteer clinics in underprivileged areas and scholarships for disadvantaged students, to empowerment through sustainability projects. An active proponent of human rights, LAU spearheaded the Global LAU Model United Nations program in Lebanon (MUN) and the LAU Model Arab League (MAL) within its Outreach and Civic Engagement Unit (OCE) to train its students in all aspects of diplomacy and negotiation while interacting with top UN representatives and high-ranking opinion makers. The university’s Global Classrooms program has been recognized for its spectacular and unmatched work in the largest Model UN program worldwide which engages more than 25,000 students and teachers annually in over 20 countries at conferences and in classrooms and holds a 16-year track record of success. www.lau.edu.lb & alumni bulletin VOLUME 18 | issue nº 1 | Spring 2016 FEATURES CONTENTS 4 another successful international conference 6 The art of reconciliation on medical education A growing body of research demonstrates that a variety of creative engagements can positively impact 10 toward an increasingly patient-centered emotions, attitudes and beliefs, contributing to greater approach individual health and wellness. -

New Business Horizons Business New Maingateamerican University of Beirut Quarterly Magazine

Fall 2009 Vol. VIII, No. 1 New Business Horizons MainGateAmerican University of Beirut Quarterly Magazine Departments: Letters 2 Inside the Gate Views from Campus OSB inaugurated on lower campus; AUBMC performs first LVAD operation 4 in Lebanon; Summer Program for AUB Alumni Children takes Beirut! Reviews 15 Beyond Bliss Street In Our History Darwin and the Evolution of AUB 44 How the scandal created by Charles Darwin’s 1882 book On the Origin of Species changed AUB’s evolutionary path. MainGate Connections Destination: Roxy 46 Over kusa mashe, remembering 1955, the AUB Women’s Hostel, and Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront. Alumni Profile Bassam Jalgha (BE ’08) has perfect pitch on The Stars of Science 48 Reflections Credit Where Credit’s Due 52 Speaking with Former Lebanese Prime Minister H.E. Salim El-Hoss Alumni Happenings New chapter leadership; President Dorman’s US tour; the new legacy 55 event for alumni parents and their children. Class Notes Hagop Pambookian (BA ’57) honored by Ohio Governor Ted Strickland; 60 Ali Krayim (BE ’61) receives the “Gold SOS Badge of Honor”; Rachel Dziecholska Rotkovitch (Nursing Diploma, ’40) to celebrate her 70th Reunion in 2010. In Memoriam 67 MainGate is published quarterly Production American University of Beirut Cover in Beirut by the American Office of Communications The new Suliman S. Olayan Office of Communications University of Beirut for Randa Zaiter School of Business. Photo by distribution to alumni, former PO Box 11–0236 Robert Fayad faculty, friends, and supporters Riad El Solh 1107 2020 worldwide. Photography CityPhoto Beirut, Lebanon Hasan Nisr Tel: 961-1-353228 Editor Nishan Simonian Fax: 961-1-363234 Ada H. -

Dissertation Title: English in Lebanon: Implications for National Identity and Language Policy

Dissertation Title: English in Lebanon: Implications for national identity and language policy Researcher: Fatima Esseili Purdue University [email protected] Fatima Esseili Research Supervisor: Dr. Margie Berns Summary: This study provides a sociolinguistic profile of English in Lebanon. It focuses on the uses of English (and French and Arabic to a lesser extent) in different venues in the Lebanese society, primarily in the capital Beirut. The study also examines the Lebanese attitudes toward mixing languages in daily speech, and attempts to provide reasons for such a trend. The project used mixed methods (observational accounts, field notes, interviews, and questionnaire) to describe the presence of foreign languages in both the social and educational contexts in Lebanon. Primary data includes results from a questionnaire (276 participants), interviews with 51 participants, and three years‟ worth of observational accounts and field notes. Findings from this study suggest that the Lebanese society is steadily transitioning to using English as the first foreign language. Findings also reveal that contrary to other Expanding Circle contexts where the mix of English and local languages is looked down upon, mixing Arabic, English, and French in Lebanon is highly regarded by more than half of the participants. Moreover, the Lebanese attitudes toward using foreign languages in general and English in particular are highly favorable. Finally, this study reveals that English language teaching (ELT) in public schools needs a thorough reevaluation from the Lebanese government, and that private schools should consider adapting ELT textbooks to the needs of the local students. References Al Haq, F. A.-A. (1996). Spread of English and Westernization in Saudi Arabia World Englishes, 15(3), 307-317. -

Hedging “Queer”/ Sexual Non- Normativity in Beirut

CROSS-BRACING SEXUALITIES: HEDGING “QUEER”/ SEXUAL NON- NORMATIVITY IN BEIRUT By Adriana Qubaiová Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Gender Studies Supervisor: Hadley Z. Renkin CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2019 Copyright Statement I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. Nor does it contain materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographic reference. th April 29 , 2019 CEU eTD Collection i Abstract Based on 15 months of ethnographic fieldwork in Beirut, this dissertation traces the (re)production of gendered non-normative sexualities as co-constituted by the local and the global. Several actors emerge as central players in shaping the meanings and politics of ‗the sexual‘ in Beirut today: the Lebanese state and its security apparatus, LGBT-rights NGOs and activists, ‗queer‘ bars, and Syrian refugees. These actors continuously configure the politics of gender and sexual non-normativity and sexual subjectivity in relation to power, profit, space, kinship, and displacement. Prevalent scholarly approaches to gender and sexual non-normativity in the Middle East (West Asia) have been caught in a debate over local authenticity on the one hand and imperial imposition and mimicry on the other. I argue for a way out of this bind. In line with post- structuralism, I propose ‗cross-bracing‘ as a theoretical structure that captures ‗the sexual‘ as a set of unequal and cross-dependent interactions among dominant forces of the local, regional, and transnational. -

Allah, Allah, Allah: the Role of God in the Arab Version of the Voice

religions Article Allah, Allah, Allah: The Role of God in the Arab Version of The Voice Jan Jaap De Ruiter 1 and Mona Farrag Attwa 1,2,* 1 Tilburg University, 5037 AB Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 Department of Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article discusses Arabic expressions referring to God, such as inshallah, mashallah, and alhamdulillah in the 2014 season of the Arab version of the talent show The Voice. It discusses the question to what extent these expressions are used by the various actors in the show, in particular its four jury members and three presenters, and it tries to explain why they use them and to what purpose. The analysis is set against the background of the question what the relationship is between ‘language’ (in this case, the various varieties of Arabic) and ‘religion’ (in this case, Christianity and Islam). The analysis yielded nearly 40 Arabic expressions referring to God (Allah or Rabb (Lord)) that together showed up more than 600 times in the 10 episodes of the show that were the object of analysis. The conclusion is that the expressions indeed have ‘religious’ roots but that they have at the same time become part and parcel of not necessarily religiously intended speaking styles expressing all kind of feelings, such as astonishment, surprise, disappointment, etc. This conclusion goes well with observations made in earlier research on the questions at stake. Keywords: expressions referring to God; varieties of Arabic; Arabic talent shows; language and religion Citation: De Ruiter, Jan Jaap, and Mona Farrag Attwa. -

Comparative Readings of the Lebanese Media System

Comparative Readings of the Lebanese Media System Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Erfurt vorgelegt von Sarah El Richani aus Choueifat (Libanon) Erfurt, 2014 urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201600105 Erstes Gutachten: Prof. Dr. Kai Hafez (Universität Erfurt) Zweites Gutachten: Prof. Jean Seaton (Universität von Westminster, London, Großbritannien) Eingereicht: 5. November 2014 Datum der Promotion: 8. April 2015 Summary The focus of this dissertation is on the Lebanese media system and the extent this system can be subsumed under one of the three ideal types put forth by Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini in their seminal work Comparing Media Systems. This endeavour uses the Hallin and Mancini framework as a scholarly springboard in an effort to take their sets of variables and models beyond the established democracies of Europe and North America. This research responds to a recurring call for comparative work and particularly for the application of the Hallin and Mancini framework on other non-Western media systems. By critically applying their framework to the Lebanese media system, this thesis assesses the complex dimensions developed by the two scholars. These include: the development of media markets, political parallelism, the degree of development of journalistic professionalism and the degree and nature of state intervention. Hallin and Mancini acknowledge that restricting themselves to the western world was a limitation. They also suggest that their work should serve as an inspiration for a process of re-modelling by adapting and reconfiguring their framework and their three ideal types to a given context. -

CONTENTS We Want, Not Conflict Between Two Adversaries

An interface between two complementary forces is what CONTENTS we want, not conflict between two adversaries. The existence of two rival camps and of two conflicting groups of media can only be a danger, but we see now incitement THE PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE to violence in districts of Beirut and at the same time the tracing of new lines of demarcation, which we thought belonged to the past, just when we were looking for construction and prosperity. There are calls for meetings of two parties or of four, and for initiatives foreign or Arab, for cooperation with the security forces, etc., etc., while at the same time the hurling of odious accusations and the laying down of futile conditions continue, together with threats of sit-ins, ACADEMIC AFFAIRS absence of authority, break-up and destructive and purposeless wars. Lebanon is no longer, as before, a land of peaceful coexistence with a message for the whole world. 3 Mission Statement - Dr. Ameen Albert Rihani Is there a reason for its continued existence? If such is the 7 USA Tour of NDU President and Vice-President case, let it have its proper place in the international arena. 8 Scholarship for Uganda Let Lebanon be a meeting place for elements representing culture, civilization and true religion. Editorial Staff March 2008 | issue 42 NDU Spirit A periodical about ACADEMIC AND STUDENT ACTIVITIES campus life at Notre Dame University - Louaïze. 9 NDU Choir in the USA WEERC Tel: (09) 218950 - Ext.: 2477 14 Workshop - the Janneh Dam Fax: (09) 218950 - Ext.: 2479 Email: [email protected] 16 LERC News www.ndu.edu.lb/newsandevents/nduspirit FAAD 21 NDU 20th Anniversary Exhibition 22 Workshop at Aleppo City - Elissar Doumit 26 Workshop: Art to Wear or Fashion? 26 NDU and Hema at Amsterdam | Editor-in-Chief Georges Mghames FH 29 Chinese in NDU | English Editor 30 Mass Communication Events Kenneth Mortimer 31 Writing Center Phase Two | Reporting FNAS Ghada Mouawad 32 First CTACCS Conference 2008 | Arabic Typing 35 Mechanical Engineering at NDU OPINION AND CULTURE Lydia Zgheïb - Dr. -

Cathrin Skog En Av Favoriterna I Miss World 2006

2006-09-18 11:21 CEST Cathrin Skog en av favoriterna i Miss World 2006 Cathrin Skog, 19 årig call-center agent från den lilla byn Nälden i närheten av Östersund är Sveriges hopp i årets Miss World 2006. Cathrins ambition i framtiden är att studera internationell ekonomi och hon älskar att måla och lyssna på musik, speciellt street, disco och funk. Hennes personliga motto i livet är att alltid se livet från den ljusa sidan och att aldrig ge upp. Finalen i Miss World 2006 kommer att hållas på lördagen den 30 september i Polen där den 56: e Miss World vinnaren kommer att koras av både en expertjury på plats och via internetröster från hela världen. Cathrin är en av förhandsfavoriterna och spelas just nu till 17 gånger pengarna. Miss Australien (Sabrina Houssami) och Miss Venezuela (Alexandra Federica Guzaman Diamante) delar på favoritskapet med spel till 8 gånger pengarna. För mer info om tävlingen, se www.missworld.com Odds Vinnarspel Miss World 2006 Miss Australia 8.00 Miss Venezuela 8.00 Miss Canada 11.00 Miss India 11.00 Miss Lebanon 13.00 Miss Angola 17.00 Miss Columbia 17.00 Miss Dominican Republic 17.00 Miss South Africa 17.00 Miss Sweden 17.00 Miss Mexico 19.00 Miss Philippines 19.00 Miss Puerto Rica 19.00 Miss Czech Republic 21.00 Miss Jamaica 21.00 Miss Martinique 21.00 Miss Spain 21.00 Miss Iceland 23.00 Miss Italy 26.00 Miss Panama 26.00 Miss Singapore 29.00 Miss Ukraine 29.00 Miss Brazil 34.00 Miss Chile 34.00 Miss China 34.00 Miss Greece 34.00 Miss Nigeria 34.00 Miss Peru 34.00 Miss Poland 34.00 Miss Turkey 34.00 Miss USA 34.00