Community Read Program Guide V.5 3.20.18 Congratulations!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 7–9, 14–16, 2020 Loft Stage at East Ridge High School MERRILL ARTS CENTER

MERRILL ARTS CENTER present a WCT production of Directed By Tom Reed February 7–9, 14–16, 2020 Loft Stage at East Ridge High School MERRILL ARTS CENTER a WCT production of WCT Production Staff Director Tom Reed so let chuck eckberg Music Director Jessie Rolfe help you find your Production Manager Leah Madsen Stage Manager MJ Luna Sound Designer Evangeline Lee dream castle! Props Designer Sarah Herman Scenic Designer Craig Steineck Costume Designer Bailey Remmers Lighting Designer Jacob Berg Even if the house isn’t in Transylvania, Choreographer Megan Torbert Chuck will electrify your journey and make sure you find MAC Administrative Staff “the happiest town” for you! Executive Director Barbe Marshall Hansen Managing Director Kajsa Jones SOS Director Kristin Fox Administrator Hannah Amidon See what a 14-time Super Real Estate AgentTM Accountant Irina Yaritz can do for you! Graphic Designer Galen Higgins Group Sales Director Alicia Wiesneth 604 Bielenberg Drive, Woodbury, MN 55125 651-246-6639 • [email protected] Publicists JAMU Enterprises www.chuckeckberg.com Director of Development Lori Nelson Digital Strategist Cromie Creative Consultants Box Office Managers Erika James, Jeriann Jones Lisa Winston MERRILL ARTS CENTER WANTED The Mission of Merrill Arts Center EMPLOYEE ENDORSEMENTS! is to champion the arts. PROGRAMS Do you work for one of these companies? Wells Fargo • Andersen Corporation • Otto Bremer Trust • Bremer Bank WCT McKnight Foundation • 3M • General Mills • Best Buy • Ecolab If yes, please let us know! AFFILIATES These companies, and many like them, have grant programs available to arts organizations like Merrill but we need an employee endorsement to apply. -

Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation

Countering the Sectarian Metanarrative: Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation Chad Day Truslow Waynesboro, Virginia B.A. in International Relations & History, Virginia Military Institute, 2008 M.A. in Business Administration, Liberty University, 2014 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures University of Virginia December, 2019 1 Abstract Sectarian conflict is a commonly understood concept that has largely shaped US foreign policy approach to the region throughout the modern Middle East. As a result of the conflict between Shia and Sunni militias in Iraq and the nature of Iraqi politics since 2003, many experts have accepted sectarianism as an enduring phenomenon in Iraq and use it as a foundation to understand Iraqi society. This paper problematizes the accepted narrative regarding the relevance of sectarian identity and demonstrates the fallacy of approaching Iraq through an exclusively “sectarian lens” in future foreign policy. This paper begins by exploring the role of the Iraqi intellectuals in the twentieth century and how political ideologies influenced and replaced traditional forms of identity. The paper then examines the common themes used by mid-twentieth century Iraqi literati to promote national unity and a sense of Iraqi identity that championed the nation’s heterogeneity. The paper then surveys the Iraqi literary response to the 2003 invasion in order to explain how some of the most popular Iraqi writers represent sectarianism in their works. The literary response to the US invasion and occupation provides a counter- narrative to western viewpoints and reveals the reality of the war from the Iraqi perspective. -

Young Frankenstein"

"YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN" SCREENPLAY by GENE WILDER FIRST DRAFT FADE IN: EXT. FRANKENSTEIN CASTLE A BOLT OF LIGHTNING! A CRACK OF THUNDER! On a distant, rainy hill, the old Frankenstein castle, as we knew and loved it, is illuminated by ANOTHER BOLT OF LIGHTNING. MUSIC: AN EERIE TRANSYLVANIAN LULLABY begins to PLAY in the b.g. as we MOVE SLOWLY CLOSER to the castle. It is completely dark, except for one room -- a study in the corner of the castle -- which is only lit by candles. Now we are just outside a rain-splattered window of the study. We LOOK IN and SEE: INT. STUDY - NIGHT An open coffin rests on a table we can not see it's contents. As the CAMERA SLOWLY CIRCLES the coffin for a BETTER VIEW... A CLOCK BEGINS TO CHIME: "ONE," "TWO," "THREE," "FOUR..." We are ALMOST FACING the front of the coffin. "FIVE," "SIX," "SEVEN," "EIGHT..." The CAMERA STOPS. Now it MOVES UP AND ABOVE the satin-lined coffin. "NINE," "TEN," "ELEVEN," "T W E L V E!" CUT TO: THE EMBALMED HEAD OF BEAUFORT FRANKENSTEIN Half of still clings to the waxen balm; the other half has decayed to skull. Below his head is a skeleton, whose bony fingers cling to a metal box. A HAND reaches in to grasp the metal box. It lifts the box halfway out of the coffin -- the skeleton's fingers rising, involuntarily, with the box. Then, as of by force of will, the skeleton's fingers grab the box back and place it where it was. Now the "Hand" -- using its other hand -- grabs the box back from the skeleton's fingers. -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

Frankenstein: Or the Modern Prometheus Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FRANKENSTEIN: OR THE MODERN PROMETHEUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley | 240 pages | 29 Jun 2011 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099512042 | English | London, United Kingdom Frankenstein: Or the Modern Prometheus PDF Book Retrieved 30 July Florescu, Radu Milner, Andrew. Archived from the original on 8 November During the two years that had elapsed previous to their marriage my father had gradually relinquished all his public functions; and immediately after their union they sought the pleasant climate of Italy, and the change of scene and interest attendant on a tour through that land of wonders, as a restorative for her weakened frame. Other motives were mingled with these, as the work proceeded. The Quarterly Review. Important Quotations Explained. In Shelley's original work, Victor Frankenstein discovers a previously unknown but elemental principle of life, and that insight allows him to develop a method to imbue vitality into inanimate matter, though the exact nature of the process is left largely ambiguous. SUNY Press. Day supports Florescu's position that Mary Shelley knew of, and visited Frankenstein Castle before writing her debut novel. Retrieved 19 September Retrieved 13 April Archived from the original on 13 February To watch the show, RSVP at www. She was not her child, but the daughter of a Milanese nobleman. These visions faded when I perused, for the first time, those poets whose effusions entranced my soul, and lifted it to heaven. American Film Institute. Mary Shelley in Her Times. He is an Englishman, and in the midst of national and professional prejudices, unsoftened by cultivation, retains some of the noblest endowments of humanity. -

Adult Fiction Adult Fiction

A Book A Book Inspired by Inspired by Another Another Literary Work Literary Work Adult Fiction Adult Fiction • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • March by Geraldine Brooks • March by Geraldine Brooks • The Master and Margarita • The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov by Mikhail Bulgakov • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits by Mary Jane Hathaway by Mary Jane Hathaway • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Ulysses by James Joyce • Ulysses by James Joyce • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son by Dean Koontz by Dean Koontz • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Fool by Christopher Moore • Fool by Christopher Moore • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Boy, -

Bamcinématek Presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 Tales of Rampaging Beasts and Supernatural Terror

BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 tales of rampaging beasts and supernatural terror September 21, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, October 26 through Thursday, November 1 BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, a series of 10 films showcasing two strands of Japanese horror films that developed after World War II: kaiju monster movies and beautifully stylized ghost stories from Japanese folklore. The series includes three classic kaiju films by director Ishirô Honda, beginning with the granddaddy of all nuclear warfare anxiety films, the original Godzilla (1954—Oct 26). The kaiju creature features continue with Mothra (1961—Oct 27), a psychedelic tale of a gigantic prehistoric and long dormant moth larvae that is inadvertently awakened by island explorers seeking to exploit the irradiated island’s resources and native population. Destroy All Monsters (1968—Nov 1) is the all-star edition of kaiju films, bringing together Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and King Ghidorah, as the giants stomp across the globe ending with an epic battle at Mt. Fuji. Also featured in Ghosts and Monsters is Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (1968—Oct 27), an apocalyptic blend of sci-fi grotesquerie and Vietnam-era social commentary in which one disaster after another befalls the film’s characters. First, they survive a plane crash only to then be attacked by blob-like alien creatures that leave the survivors thirsty for blood. In Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960—Oct 28) a man is sent to the bowels of hell after fleeing the scene of a hit-and-run that kills a yakuza. -

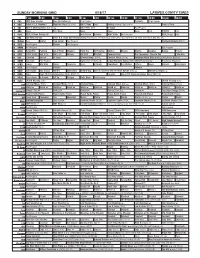

Sunday Morning Grid 6/18/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/18/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Paid Program 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Sailing America’s Cup. (N) Å Track & Field 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid XTERRA Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday 2017 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. The final round of the 2017 U.S. Open tees off. From Erin Hills in Erin, Wis. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Northern Borders (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVY) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Concrete River The Carpenters: Close to You Pavlo Live 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) El Que No Corre Vuela (1982) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. -

Dracula As Inter-American Film Icon: Universal Pictures and Cinematográfica ABSA

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar English, Linguistics, and Communication College of Arts and Sciences 2020 Dracula as Inter-American Film Icon: Universal Pictures and Cinematográfica ABSA Antonio Barrenechea Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/elc Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Review of International American Studies VARIA RIAS Vol. 13, Spring—Summer № 1 /2020 ISSN 1991—2773 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31261/rias.8908 DRACULA AS INTER-AMERICAN FILM ICON Universal Pictures and Cinematográfca ABSA introduction: the migrant vampire In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Jonathan Harker and the Tran- Antonio Barrenechea University of sylvanian count frst come together over a piece of real estate. Mary Washington The purchase of Carfax Abbey is hardly an impulse-buy. An aspir- Fredericksburg, VA ing immigrant, Dracula has taken the time to educate himself USA on subjects “all relating to England and English life and customs https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1896-4767 and manners” (44). He plans to assimilate into a new society: “I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is” (45). Dracula’s emphasis on the roar of London conveys his desire to abandon the Carpathian Mountains in favor of the modern metropolis. Transylvania will have the reverse efect on Harker: having left the industrial West, he nearly goes mad from his cap- tivity in the East. -

Frankenstein

Frankenstein Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus Author Mary Shelley Country United Kingdom Language English Genre Gothic novel, horror fiction, science fiction[1] Set in England, Ireland, Italy, France, Scotland, Switzerland, Russia, Germany; late 18th century Published 1 January 1818 (Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor & Jones) Pages 280 Dewey 823.7 Decimal LC Class PR5397 .F7 Text Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus at Wikisource Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a novel written by English author Mary Shelley (1797–1851) that tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a hideous sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific experiment. Shelley started writing the story when she was 18, and the first edition was published anonymously in London on 1 January 1818, when she was 20.[2] Her name first appeared in the second edition published in Paris in 1821. Shelley travelled through Europe in 1815 along the river Rhine in Germany stopping in Gernsheim, 17 kilometres (11 mi) away from Frankenstein Castle, where two centuries before, an alchemist engaged in experiments.[3][4][5] She then journeyed to the region of Geneva, Switzerland, where much of the story takes place. The topic of galvanism and occult ideas were themes of conversation among her companions, particularly her lover and future husband Percy B. Shelley. Mary, Percy and Lord Byron had a competition to see who could write the best horror story. After thinking for days, Shelley dreamt about a scientist who created life and was horrified by what he had made, inspiring the novel.[6] Though Frankenstein is infused with elements of the Gothic novel and the Romantic movement, Brian Aldiss has argued that it should be considered the first true science fiction story. -

{Download PDF} in Odd We Trust Kindle

IN ODD WE TRUST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean Koontz | 224 pages | 01 Jul 2008 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007236961 | English | London, United Kingdom In Odd We Trust PDF Book Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters. I understand Dean Koontz's interest in experimenting with different story telling formats and loo I like the Odd Thomas character and when I saw this graphic novel was intrigued to see how they approached the story. In Odd We Trust 4. The characters were so far removed from their novel counterparts that Odd was barely more than a boy who walked from scene to scene just to tie the story together and for some reason Sto I don't really have much good to say about this graphic novel. Ian Edginton. It doesn't end like Erin Hunter's graphic books where the books are serialized. The characters were so far removed from their novel counterparts that Odd was barely more than a boy who walked from scene to scene just to tie the story together and for some reason Stormy had been turned into an angry gun- toting maniac. I haven't ever read any Dean Koontz novels before, and I have to say that this does not give me the desire to do so. It was awful. Garth Ennis and Jamie Delano. We use cookies to give you the best online experience. Trisha — Jul 02, Picked this up at a used bookstore, and thought "Huh! I've heard of soul mates and stuff which I can understand it to an extent but in this graphic novel I just couldn't get a sense for it. -

Frankenstein: the Dead Town: a Novel PDF Book

FRANKENSTEIN: THE DEAD TOWN: A NOVEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean R Koontz | 423 pages | 26 Oct 2012 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553593686 | English | New York, United States Frankenstein: the Dead Town: a Novel PDF Book To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. It syncs automatically with your account and allows you to read online or offline wherever you are. Helios has acquired wealth and power from selling his knowledge to, among others, Adolf Hitler , Joseph Stalin , and the People's Republic of China. Our insipid band of idiots, I mean heroes find weird bits of flesh all over the place, some look almost normal and others have weird shit like extra body parts growing out of them. A member of the New Race. Others fainted. Im still upset that this didn't become a movie or series. A little girl in Las Vegas. Opposed to his activities are a pair of homicide detectives and Frankenstein's original monster , now known as Deucalion. I think they also went a little ape-shit in the first two books, Prodigal Son and City of Night. Michael Richan writes it and there are multiple series that all take place within the one universe. A dark memory is calling out to them. Now the master of suspense delivers an unforgettable novel that is at once a thrilling adventure in itself and a mesmerizing conclusion to his saga of the modern monsters among us. Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. I drug this one out because I am going to miss Deucalion! First, there is Deucalion, Helios original creation.