Shakespeare's Industry, by Mrs. C.C. Stopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Handbook of Rules and Regulations

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF RULES AND REGULATIONS 2021 | 69th EDITION AMERICAN QUARTER HORSE An American Quarter Horse possesses acceptable pedigree, color and mark- ings, and has been issued a registration certificate by the American Quarter Horse Association. This horse has been bred and developed to have a kind and willing disposition, well-balanced conformation and agile speed. The American Quarter Horse is the world’s most versatile breed and is suited for a variety of purposes - from working cattle on ranches to international reining competition. There is an American Quarter Horse for every purpose. AQHA MISSION STATEMENT • To record and preserve the pedigrees of the American Quarter Horse, while maintaining the integrity of the breed and welfare of its horses. • To provide beneficial services for its members that enhance and encourage American Quarter Horse ownership and participation. • To develop diverse educational programs, material and curriculum that will position AQHA as the leading resource organization in the equine industry. • To generate growth of AQHA membership via the marketing, promo- tion, advertising and publicity of the American Quarter Horse. • To ensure the American Quarter Horse is treated humanely, with dignity, respect and compassion, at all times. FOREWORD The American Quarter Horse Association was organized in 1940 to collect, record and preserve the pedigrees of American Quarter Horses. AQHA also serves as an information center for its members and the general public on matters pertaining to shows, races and projects designed to improve the breed and aid the industry, including seeking beneficial legislation for its breeders and all horse owners. AQHA also works to promote horse owner- ship and to grow markets for American Quarter Horses. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

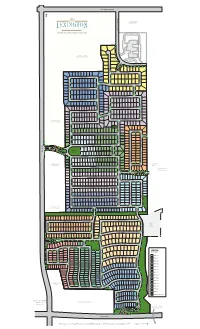

Lexington Phases Mastermap RH HR 3-24-17

ELDORADO PARKWAY MAMMOTH CAVE LANE CAVE MAMMOTH *ZONED FUTURE LIGHT RETAIL MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY MAJESTIC PRINCE CIRCLE MAMMOTH CAVE LANE T IN O P L I A R E N O D ORB DRIVE ARISTIDES DRIVE MACBETH AVENUE MANUEL STREETMANUEL SPOKANE WAY DARK STAR LANE STAR DARK GIACOMO LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDSTONE MANOR GRINDSTONE FUNNY CIDE COURT FUNNY THUNDER GULCH WAY BROKERS TIP LANE MANUEL STREETMANUEL E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND TRAIL LEONATUS LANE LEONATUS PONDER LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTERGREEN DRIVE COIT ROAD COIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD COUNT TURF COUNT DRIVE AMENITY SMARTY JONES STREET CENTER STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD 2 DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY 5 CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 1 Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE FLYING EBONY STREET LIGHT RETAIL Park AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE CONQUISTADOR COURT CONQUISTADOR LUCKY DEBONAIR LANE LUCKY OXBOW AVENUE OXBOW CAVALCADE DRIVE CAVALCADE 4 WHIRLAWAY DRIVE 9 IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER ROAD C WAR EMBLEM PLACE WAR A N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R I V E 14DUST COMMANDER COURT CIRCLE PASS FORWARD DETERMINE DRIVE SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUIET RD. TIM TAM CIRCLE EASY GOER AVENUE LEGEND PILLORY DRIVE PILLORY BY PHASES HALMA HALMA TRAIL 11 PHASE 1 A PROUD CLAIRON STREET M E MIDDLEGROUND PLACE -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

Jockey Records

JOCKEYS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2020) Most Wins Jockey Derby Span Mts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Eddie Arcaro 1935-1961 21 5 3 2 Lawrin (1938), Whirlaway (’41), Hoop Jr. (’45), Citation (’48) & Hill Gail (’52) Bill Hartack 1956-1974 12 5 1 0 Iron Liege (1957), Venetian Way (’60), Decidedly (’62), Northern Dancer-CAN (’64) & Majestic Prince (’69) Bill Shoemaker 1952-1988 26 4 3 4 Swaps (1955), Tomy Lee-GB (’59), Lucky Debonair (’65) & Ferdinand (’86) Isaac Murphy 1877-1893 11 3 1 2 Buchanan (1884), Riley (’90) & Kingman (’91) Earle Sande 1918-1932 8 3 2 0 Zev (1923), Flying Ebony (’25) & Gallant Fox (’30) Angel Cordero Jr. 1968-1991 17 3 1 0 Cannonade (1974), Bold Forbes (’76) & Spend a Buck (’85) Gary Stevens 1985-2016 22 3 3 1 Winning Colors (1988), Thunder Gulch (’95) & Silver Charm (’98) Kent Desormeaux 1988-2018 22 3 1 4 Real Quiet (1998), Fusaichi Pegasus (2000) & Big Brown (’08) Calvin Borel 1993-2014 12 3 0 1 Street Sense (2007), Mine That Bird (’09) & Super Saver (’10) Victor Espinoza 2001-2018 10 3 0 1 War Emblem (2002), California Chrome (’14) & American Pharoah (’15) John Velazquez 1996-2020 22 3 2 0 Animal Kingdom (2011), Always Dreaming (’17) & Authentic (’20) Willie Simms 1896-1898 2 2 0 0 Ben Brush (1896) & Plaudit (’98) Jimmy Winkfield 1900-1903 4 2 1 1 His Eminence (1901) & Alan-a-Dale (’02) Johnny Loftus 1912-1919 6 2 0 1 George Smith (1916) & Sir Barton (’19) Albert Johnson 1922-1928 7 2 1 0 Morvich (1922) & Bubbling Over (’26) Linus “Pony” McAtee 1920-1929 7 2 0 0 Whiskery (1927) & Clyde Van Dusen (’29) Charlie -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue and Price List of Stereopticons

—. ; I, £3,v; and Descriptive , Illustrated ;w j CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST- t&fs — r~* yv4 • .'../-.it *.•:.< : .. 4^. ; • ’• • • wjv* r,.^ N •’«* - . of . - VJ r .. « 7 **: „ S ; \ 1 ’ ; «•»'•: V. .c; ^ . \sK? *• .* Stereopticons . * ' «». .. • ” J- r . .. itzsg' Lantern Slides 1 -f ~ Accessories for Projection Stereopticon and Film Exchange W. B. MOORE, Manager. j. :rnu J ; 104 to no Franlclin Street ‘ Washington . (Cor. CHICAGO INDEX TO LANTERNS, ETC. FOR INDEX TO SLIDES SEE INDEX AT CLOSE OF CATALOGUE. Page Acetylene Dissolver 28 Champion Lantern 3g to 42 “ Gas 60 Check Valve S3 •* 1 • .• Gas Burner.... ; 19 Chemicals, Oxygen 74, 81 ** < .' I j Gas Generator.. ; 61 to 66 Chirograph 136 “ Gas Generator, Perfection to 66 64 Chlorate of Potash, tee Oxygen Chemicals 74 Adapter from to sire lenses, see Chromatrope.... 164 Miscellaneous....... 174 Cloak, How Made 151 Advertising Slides, Blank, see Miscellaneous.. 174 ** Slides 38010,387 " Slides 144 Color Slides or Tinters .^140 “ Slides, Ink for Writing, see Colored Films 297 Miscellaneous, 174 Coloring Films 134 “ Posters * *...153 " Slides Alcohol Vapor Mantle Light 20A v 147 Combined Check or Safety Valve 83 Alternating.Carbons, Special... 139 Comic and Mysterious Films 155 Allen Universal Focusing Lens 124, 125 Comparison of Portable Gas Outfits 93, 94 America, Wonders cf Description, 148 “Condensing Lens 128 Amet's Oro-Carbi Light 86 to 92, 94 " Lens Mounting 128 •Ancient Costumes ....! 131 Connections, Electric Lamp and Rheostat... 96, 97 Approximate Length of Focus 123 " Electric Stage 139 Arc Lamp 13 to 16 Costumes 130 to 152, 380 to 3S7 ** Lamp and Rheostat, How to Connect 96 Cover Glasses, see Miscellaneous ,....174 Arnold's Improved Calcium Light Outfit. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Cui.U.K. &3o 1 THE LIVES OK THE CHIEF JUSTICES ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D. F.E.S.E.: AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LOKD CHANCELLORS OF ENGLANd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUR VOLUMES.— Vol. II. LONDON: JOHN MUEKAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. Uniform with the present Work. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOBS, AND Keepers op the Great Skal op England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s. ' each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we arc satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt If there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the iearned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Review. &ONdON: PRINTEd BT WILLIAM CLOWES ANd SONS, STAMFORd STREET ANd CHARING CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. CHAPTER XI.— continued. LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES FROM THE DISMISSAL OF SIR EDWARD COKE TILL THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. Sir Nicholas Hyde, Page 1. His Reputation as a Lawyer, 1. His Con duct as Chief Justice of the King's Bench, 2. -

Boost Buchanan

V O L U M E X U . BUCHANAN, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, AUGUST 23, 1907 N U M B E R m SOUTH ORONOKO Correspondence The Record’s Regular Correspondent. South Oronoko, Aug. 22—The I iBOOST-BUCHANAN , machinery for the new creamery is J O r e g o n M y WEST BERTRAND sing put in this week. The coin-j Tke Kteud’i Beg tier. Correspoadeat. panj;expect to begin receiving milk] next week. OivnHpi^d^frqm teat Issue ^ West -Bertrand, Aug.22— Miss, Bes sie .Curtis, of Harrington, Del., is a A new coat of paint adorns the] guest at'the .John Redden home. present .residence Of Geo. Burgoyne. West Michigan State Fair Erects Our friend is living on e newplace, for-congas that night. vBut we were; > films Jessie Smith, of*Bristol;Ind.j *Wm. -McCracken is putting his ten. Fine Structure. only -afew seres cleared. They are all safethe next morning That night was. a guest o f Miss Dorothea Currier ant house in condition for occupancy. | we -hadfir.boughsfor abed. Mere BOOST BUCHANAN conipletely<snrrounded byTorest.-Hi* Monday. farm of 128jacrea coat-hua-* :litiie. rWUc-caught our^ first- trout out o f the One of the pioneer land marks; the I LONG FELT WANT IS NOW MET WITH Bernice Ferguson visited South .house built by Wm. Tabor, has been | over $600. It is fertile, soil, &inti&w,friyer. - We followed 'this A Ne w1 Telephone with5 Free Service do . torn down. river to the ocean. ^ BenoL frien d s several days last week. ail o f Niles’ List. -

Lex Mastermap Handout

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D .