We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For: Pan-African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threats to Academic Freedom in Venezuela: Legislative Im- Positions and Patterns of Discrimination Towards University Teachers and Students

Interdisciplinary Political Studies http://siba-ese.unisalento.it/index.php/idps ISSN: 2039 -8573 (electronic version) IdPS, Issue 3(1) 2017: 145-169 DOI: 10.1285/ i20398573v3n1p145 Published in December 11, 2017 RESEARCH ARTICLE 145 Threats to Academic Freedom in Venezuela: Legislative Im- positions and Patterns of Discrimination Towards University Teachers and Students Mayda Hocevar Nelson Rivas University of Los Andes – Venezuela University of Los Andes – Venezuela David Gómez University of Zulia – Venezuela ABSTRACT As democracy is weakened and economic and social conditions deteriorate, there are increasing threats to academic freedom and autonomy in Venezuelan universities. Although academic freedom and university autonomy are legally and constitutionally recognized, public policies and ‘new legisla- tion’ undermine them. Military and paramilitary forces violently repress student protests. Frequent- ly, students are arbitrarily detained, physically attacked, and psychologically pressured through in- terrogations about their political views and their supposed "plans to destabilize the government". A parallel system of non-autonomous universities has been created under a pensée unique established by the Socialist Plans of the Nation. Discrimination has increased, both in autonomous and non- autonomous universities. This paper will expose the legal and political policies undermining aca- demic freedom in Venezuela under the governments of former president Hugo Chávez and current president Nicolás Maduro. Patterns of attacks against -

Extensions of Remarks 10509

May 9, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 10509 MENT REPORT.-The Secretary shall set forth available to the United States Geological -Page 274, line 1, strike "(b) (1)" and in in each report to the Congress under the Survey, the Bureau of Mines, or any other lieu thereof insert "(c) (2)". Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970 a agency or instrumentality of the United Page 333, lines 14 and 15, strike "after the summary of the pertinent information States. date of enactment of this Act". (other than proprietary or other confidential (Additional technical amendments to -Page 275, line 8, change "28" to "27" and information) relating to minerals which is Udall-Anderson substitute (H.R. 3651) .) change "33" to "34". EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A NONFUEL MINERAL POLICY: WE Of course, the usual antagonists are lined These Americans descend from .Japa CAN NO LONGER WAIT up on each side of this policy debate. But, nese, Chinese, Korean, and Filipino an as Nevada Congressman J. D. Santini points cestors, as well as from Hawaii and t'iher out in our p . 57 feature, their arguments Pacific Islands such as Samoa, Fiji, and HON. JIM SANTINI go by one another like ships in the night with nothing happening-until the lid blows Tahiti. In southern California, where OF NEVADA off. we have the greatest concentration of IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES But, how do you get the public excited Asian and Pacific Americans anywhere Wednesday, May 9, 1979 about metal shortages? in the Nation, their valuable involvemept Even Congressman Santini's well-meant in the growth and prosperity of our local • Mr. -

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Erie's Mayor Speaks on the Rise in Crime and Violence in the City

The local voice for news, arts, and culture. with SINNOTT Erie’s Mayor Speaks on the Rise in Crime and Violence in the City August 5 - 18, 2015 / Vol. 5, No. 16 / ErieReader.com ATTACK OF BEARDED BABY THE PACA CELEBRATE ERIE GALLABALOO SUMMER JAM AT BT IS TODAY THE DAY YOU IGNITE YOUR FUTURE? If you have the spark, we have the programs to guide you toward a rewarding career. FORTIS offers programs in the following areas: Nursing • Medical/Dental • Business I.T. • Skilled Trades • Cosmetology CALL 1.800.555.7600 TEXT “IGNITE” TO 367847 FORTIS.EDU IGNITE YOUR FUTURE FORTIS INSTITUTE 5757 WEST 26TH STREET, ERIE, PA 16506 Financial Aid Available for those who qualify. Career Placement Assistance for All Graduates. For consumer information, visit Fortis.edu. From The Editors ter @Snevets_Yaj, as he’ll soon be launch- ing a podcast amongst what we’re sure or better or for worse, Erie has spent in search of a silver-bullet-proof-vest an- will be many other creative ventures. nearly a decade with Mayor Joe Sin- swer but to offer a longform interview he next installment of Erie Gives Fnott. And for better or for worse, that would fill as many pages as possible TDay falls on Tuesday, Aug. 11. From 8 Sinnott, who ran unopposed for his final and address as many topics as they could a.m. to 8 p.m., Erieites have a twelve-hour of three terms, reaching the imposed limit fit in. window to donate to the nonprofit of on all mayors after Lou Tullio’s two-de- Does it answer everything? No. -

Exploring Hugo Chávez's Use of Mimetisation to Build a Populist

Exploring Hugo Chávez’s use of mimetisation to build a populist hegemony in Venezuela Elena Block Rincones MSc, BA A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Journalism and Communication Abstract “You too are Chávez”… (Hugo Chávez, 2012i) This thesis examines the political communication style developed by Hugo Chávez in his hegemonic construction of power and collective identity during the 14 years he governed Venezuela. This thesis is located in the field of political communication. A culturalist approach is used for the case, which prioritises issues of culture and power and acknowledges the role of human agency. Thus, it specifically focuses on the way the late President appears to have incrementally built an emotional, mimetic bond with his publics in a process that culminated in the mimetisation of the leader and his followers in a new collective, but top-down, identity called Chávez. This process expresses a hegemonic dynamic that involved the displacement of former dominant groups and rearrangement of power relations in Venezuela. The logic of mimetisation proposes an incremental logic of articulation whereby I tried to make sense of Chávez’s political communication style and success. It involves the study of the thread that joined together key elements in Chávez’s political communication style: hegemony and identity construction, political culture, populism, mediatisation, and communicational government. It is a style that appears to have exceeded classic populist forms of communication based on exerting an appeal to the people, towards more inclusive, participatory, symbolic-pragmatic forms of practising political communication that may have constituted the key to Chávez’s political success for 14 years. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTIONS FOR TRANSPORT urban transport GLOBAL ENGINEERING AND CONSULTANCY Ineco Ineco is a global leader in transport engineering and consultancy. For over 45 years, its expert team of around 2,500 employees has been contributing to the development of infrastructures in the aviation, railways, roads, urban transport and port sectors, offering solutions in more than 45 countries. Global leader in transport engineering and consultancy EXPERTS IN TRANSPORT Experts Experts in engineering and consultancy on airports, air traffic, conventional and high-speed railway systems, logistics, urban transport, ports and roads. MULTIMODAL PROJECTS Markets AVIATION RAILWAYS We provide the knowledge in ROADS engineering and consultancy our clients need for the URBAN development and management TRANSPORT of their transport systems. PORTS This knowledge extends to all BUILDING sectors: aviation (including air transport, airports and air navigation), railways, roads, urban and sea transport and building. MULTIMODAL PROJECTS PLANNING Solutions DESIGN Ineco offers comprehensive and CONSULTANCY innovative solutions for all phases of a project, from feasibility WORKS studies to the commissioning and OPERATION AND execution, including the MAINTENANCE improvement of management, operational and maintenance PROJECT MANAGEMENT processes. SYSTEMS ENVIRONMENT INECO AND INNOVATION Innovation at the service of transport Ineco invests in research, development and innovation to increase the competitiveness and the quality of its services. Algeria Mali Argentina -

Sabaneta to Miraflores: Afterlives of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela

Sabaneta to Miraflores: Afterlives of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela The inner-city parish of La Vega sits in the lush mountain terrain of Western Caracas. Roughly 130,000 poor residents are cordoned off sociologically from nearby El Paraíso, a wealthy neighborhood that supplies the clients for the upscale shopping center that separates the two communities. In La Vega, the bottom 20 percent of households live on US$125 per month, while the average family income is $US409. Well over a third of households are led by a single mother. Proletarians of mixed African, indigenous, and European ancestries populate the barrio’s informal economies.[1] In Venezuela, one of the most urbanized countries in Latin America, these households constitute a key demographic base of chavismo. Six years ago, the journalist Jacobo Rivero asked a 50-year-old black woman from La Vega what would happen if Chávez died. The Bolivarian process “is irreversible,” she told him, its roots are too deep to be easily torn asunder in the absence of el comandante. In the years since Chávez’s rise to the presidency in 1999—an interval of unprecedented popular political participation and education for the poor—the woman had learned, for the first time, the history of African slavery and the stories of her ancestors. The historical roots of injustice were being demystified, their causes sorted out. Dignity was being restored in inner-city communities, and their political confidence was on the rise. There had been motive, it now seemed to her, behind the manufactured ignorance of the -

Smart Villages in West Africa: Accra Regional Workshop Report

Smart Villages in West Africa: Accra regional workshop report Workshop Report 20 May 2016 ACCRA, GHANA Key words: West Africa, Energy Access, Rural Development, Off-grid energy Smart Villages We aim to provide policymakers, donors, and development agencies concerned with rural energy access with new insights on the real barriers to energy access in villages in developing countries— technological, financial and political—and how they can be overcome. We have chosen to focus on remote off-grid villages, where local solutions (home- or institution-based systems and mini-grids) are both more realistic and cheaper than national grid extension. Our concern is to ensure that energy access results in development and the creation of “smart villages” in which many of the benefits of life in modern societies are available to rural communities. www.e4sv.org | [email protected] | @e4SmartVillages CMEDT – Smart Villages Initiative, c/o Trinity College, Cambridge, CB2 1TQ Publishing © Smart Villages 2016 The Smart Villages Initiative is being funded by the Cambridge Malaysian Education and Development Trust (CMEDT) and the Malaysian Commonwealth Studies Centre (MCSC) and through a grant from the Templeton World Charity Foundation (TWCF). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Cambridge Malaysian Education and Development Trust or the Templeton World Charity Foundation. This publication may be reproduced in part or in full for educational or other non-commercial purposes. SMART VILLAGES -

Tributaries 2013

1 2 TRIBUTARIES Tributaries 2012-2013 Staff Editors-in-Chief: Ian Holt and Deidra Purvis Fiction Editor: Chase Eversole Nonfiction Editor: Emily O’Brien Poetry Editor: Andrew Davis Art & Design Editor: Kaylyn Flora Copy Editor: Chase Eversole Faculty Advisors: Beth Slattery and Tanya Perkins 3 Our Mission Ridicule is the tribute paid to the genius by the mediocrities. ––Oscar Wilde Tributaries is a student-produced literary and arts journal published at Indiana University East that seeks to publish invigorating and multifaceted fiction, nonfiction, poetry, essays, and art. Our modus operandi is to do two things: Showcase the talents of writers and artists whose work feeds into a universal body of creative genius while also paying tribute to the greats who have inspired us. We accept submissions on a rolling basis and publish on an annual schedule. Each edition is edited during the fall and winter months, which culminates with an awards ceremony and release party in the spring. Awards are given to the best pieces submitted in all categories. Tributaries is edited by undergraduate students at Indiana University East. 4 TRIBUTARIES Table of Contents Art “Arty art” Danielle Standley Covers “See The Love Pt. 1” Jami Dingess 7 “Never Knew Love ‘Til Now” Jami Dingess 49 “See The Love Pt. 2” Jami Dingess 75 “Monsters in Paradise” Jami Dingess 100 Fiction “The Right Hand Pocket” Ryland McIntyre 9 “Book ‘Em” Krisann Johnson 12 “Nude” Brittany Hudson 14 “The Enemy Within” Lynn Loring 19 “Vance Grafton” Heather Barnes 20 “Part One: The Sock Bandits” -

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education Jeff Denight, Dramaturgy Intern 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Historical Context 6 Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Knipper and Chekov in Their Own Words 6 3) The Development of The Lady Onstage 8 4) Considering Contemporary Cultural Shifts (Homework) 9 Supplemental Materials 10 Lesson 2: The Process of Play Development 21 Classroom Activities 1) Where Do New Plays Come From? 21 2) Exploring a Play We Know 23 3) How to Start - the Development Process in Action 24 4) Starting Your Own Play (Homework) 24 Supplemental Materials 26 Lesson 3: One Person Plays - A Unique Challenge 34 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Single-Character Monologues 34 2) Exploring Multi-character Solo Performances 35 3) Writing Your Own Monologue (Homework) 36 Supplemental Materials 38 Lesson 4: Chekhov Today: Translations and Adaptations 41 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Translations 42 2) Exploring Work Inspired by Chekhov 42 3) Creating Your Own Adaptation 43 Supplemental Materials 44 Lesson 5: Reflecting on the Performance Classroom Activities 1) Classroom Discussion and Reflection 52 2) What We’ve Learned 52 3) Creative Writing (Homework) 53 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. Each year Profile produces a season of plays devoted to a single playwright, engaging with our community to explore that writer’s vision and influence on theatre and the world at large. -

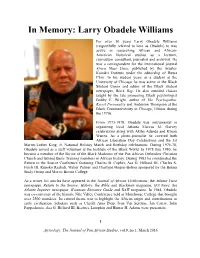

In Memory: Larry Obadele Williams

In Memory: Larry Obadele Williams For over 30 years Larry Obadele Williams (respectfully referred to here as Obadele) to was active in researching African and African- American historical studies as a lecturer, curriculum consultant, journalist and archivist. He was a correspondent for the international journal Africa Must Unite, published by the Arusha- Konakri Institute under the editorship of Ruwa Chiri. In his student years as a student at the University of Chicago, he was active in the Black Student Union and editor of the Black student newspaper, Black Rap. He also attended classes taught by the late pioneering Black psychologist Bobby E. Wright, author of The Psychopathic Racist Personality and Anderson Thompson at the Black Communiversity in Chicago, Illinois during the 1970s. From 1973-1978, Obadele was instrumental in organizing local Atlanta Marcus M. Garvey celebrations along with Akiba Adande and Khusu Wanzu. As a photo-journalist he covered both African Liberation Day Celebrations and the 1st Martin Luther King, Jr. National Holiday March and Birthday celebrations. During 1976-78, Obadele served as a staff volunteer at the Institute of the Black World. In 1978 thru 1980, he became a member of the Shrine of the Black Madonna of the Pan African Orthrodox Christian Church and tutored Basic Training members in African history. During 1983 he coordinated the Return to the Source Conference featuring Charles B. Copher, Asa G. Hilliard III, Charles S. Finch III, Runoko Rashidi, Walter Palmer and Charlyne Harper-Bolton sponsored by the Bennu Study Group and Morris Brown College. As a writer, his articles have appeared in the Journal of African Civilizations, the Atlanta Voice newspaper, Return to the Source, History, the Bible and Blackman magazine, IFA News, the Atlanta Inquirer newspaper, Kwanzaa Resource Guide and RAW magazine.