Songs of Struggle in the Film Sarafina!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Making memory work: Performing and inscribing HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa Thesis How to cite: Doubt, Jenny Suzanne (2014). Making memory work: Performing and inscribing HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000eef6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Making Memory Work: Performing and Inscribing HIV I AIDS in Post-Apartheid South Africa Jenny Suzanne Doubt (BA, MA) Submitted towards a PhD in English Literature at the Open University 5 July 2013 1)f\"'re:. CC ::;'.H':I\\\!:;.SIOfl: -::\ ·J~)L'I ..z.t.... L~ Vt',':·(::. 'J\:. I»_",i'~,' -: 21 1'~\t1~)<'·i :.',:'\'t- IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk PAGE NUMBERING AS ORIGINAL Jenny Doubt Making Memory Work: Performing and Inscribing HIV/AIDS in Post-Apartheid South Africa Submitted towards a PhD in English Literature at the Open University 5 July 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that the cultural practices and productions associated with HIV/AIDS represent a major resource in the struggle to understand and combat the epidemic. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each orignal is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 AMBIGUITY AND DECEPTION IN THE COVERT TEXTS OF SOUTH AFRICAN THEATRE: 1976-1996 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Allan John Munro, M.A., H.D.E. -

Black Theatre Movement PREPRINT

PREPRINT - Olga Barrios, The Black Theatre Movement in the United States and in South Africa . Valencia: Universitat de València, 2008. 2008 1 To all African people and African descendants and their cultures for having brought enlightenment and inspiration into my life 3 CONTENTS Pág. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………………………………………………… 6 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………….. 9 CHAPTER I From the 1950s through the 1980s: A Socio-Political and Historical Account of the United States/South Africa and the Black Theatre Movement…………………. 15 CHAPTER II The Black Theatre Movement: Aesthetics of Self-Affirmation ………………………. 47 CHAPTER III The Black Theatre Movement in the United States. Black Aesthetics: Amiri Baraka, Ed Bullins, and Douglas Turner Ward ………………………………. 73 CHAPTER IV The Black Theatre Movement in the United States. Black Women’s Aesthetics: Lorraine Hansberry, Adrienne Kennedy, and Ntozake Shange …………………….. 109 CHAPTER V The Black Theatre Movement in South Africa. Black Consciousness Aesthetics: Matsemala Manaka, Maishe Maponya, Percy Mtwa, Mbongeni Ngema and Barney Simon …………………………………... 144 CHAPTER VI The Black Theatre Movement in South Africa. Black South African Women’s Voices: Fatima Dike, Gcina Mhlophe and Other Voices ………………………………………. 173 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………… 193 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………………………… 199 APPENDIX I …………………………………………………………………………… 221 APPENDIX II ………………………………………………………………………….. 225 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing this book has been an immeasurable reward, in spite of the hard and critical moments found throughout its completion. The process of this culmination commenced in 1984 when I arrived in the United States to pursue a Masters Degree in African American Studies for which I wish to thank very sincerely the Fulbright Fellowships Committee. I wish to acknowledge the Phi Beta Kappa Award Selection Committee, whose contribution greatly helped solve my financial adversity in the completion of my work. -

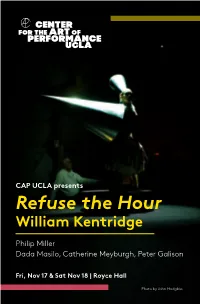

William Kentridge

CAP UCLA presents Refuse the Hour William Kentridge Philip Miller Dada Masilo, Catherine Meyburgh, Peter Galison Fri, Nov 17 & Sat Nov 18 | Royce Hall Photo by John Hodgkiss East Side, MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR West Side, All Around LA Welcome to the Center for the Art of Performance The Center for the Art of Performance is not a place. It’s more of a state of mind that embraces experimentation, encourages Photo by Ian Maddox a culture of the curious, champions disruptors and dreamers and One would have to admit that the masterful work of William Kentridge leaves supports the commitment and courage of artists. We promote virtually no artistic discipline unexplored, untampered with, or under-excavated in rigor, craft and excellence in all facets of the performing arts. service to his vigilant engagement with the known world. He has done x, y z, p, d, q, (installations, exhibitions, theater works, prints, drawings, animations, innumerable collaborations, etc.) and then some, over the arc of his career and there is nothing on the horizon line of his trajectory that indicates any notion of relenting any time 2017–18 SEASON VENUES soon. Royce Hall, UCLA Freud Playhouse, UCLA Over the years I have been asked to offer explanations and descriptions of the The Theatre at Ace Hotel Little Theater, UCLA works of William Kentridge while encountering it in numerous occasions around the Will Rogers State Historic Park world. As a curator, one is expected to possess the necessary expertise to rapidly summarize dimensional artistry. But in a gesture of truth, my attempts fail in UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) is dedicated to the advancement juxtaposition to the vastly better reality of experiencing his utter artistic singularity, of the contemporary performing arts in all disciplines—dance, music, spoken word and the staggering dimension of thoughtful care he takes in finding form. -

Girl Talk Curriculum Cycle Two

GIRL TALK CURRICULUM CYCLE TWO GIRL TALK STATEMENT (April 2011): LOCKING GIRLS UP ISN’T GENDER-RESPONSIVE BUT WE STILL HAVE TO SUPPORT INCARCERATED GIRLS… Introduction: Every night, between 25 to 50 girls lay their heads on pillows in 7.5 by 14.5 foot cells at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (JTDC). These girls have prior histories of sexual and physical abuse (Bloom et al 2003); they are suffering from depression (Obeidallah and Earls 1999); they are poor, disproportionately from racial minority groups (Moore and Padavic 2010); they transgress gender identity norms and are punished for it (Dang 1997); some are battling addiction; and many are under-educated. These are the young people that society has left behind and wants to erase from our consciousness. The most important thing that we can do then is to insist that young women in conflict with the law be made visible and that their voices be heard. Across the United States, girls are the fastest growing youth prison population. Due to an over-reliance on the criminalization of social problems in the last two decades leading up to the twenty-first century, arrest and detention rates of U.S. girls soared to almost three-quarters of a million in 2008 (Puzzanchera 2009). By 2009, girls comprised 30 percent of all juvenile arrests. Many observers suggest that youth behavior has not changed during this period; it was society’s response to such behavior that had changed. Regardless, the result of our punishing culture is that thousands of young women are shuffled through police stations, detention facilities and probation departments across the nation annually. -

Burying the Bones

Discovery Guide prepared by Laura Lynn MacDonald October 4-27, 2013 To purchase tickets: 414-271-1371 In Tandem Theatre 628 N. 10th Street Milwaukee, WI 53233 www.intandemtheatre.org 1 The Discovery Guide was developed by In Tandem Theatre to enrich your understanding and enjoyment of M.E.H. Lewis’s Burying the Bones. (Burying the Bones contains graphic depictions of violence and is recommended for mature audiences over thirteen years old). Table of contents: Welcome to In Tandem Theatre Company................................................ 3 Note from Director Chris Flieller.............................................................. 4 Synopsis of Burying the Bones................................................................. 5 Characters & Setting................................................................................ 6 Images from Apartheid............................................................................ 7 About the Playwright............................................................................... 8 Interview with Playwright M.E.H. Lewis.................................................. 9 Artistic Team: Staff and Cast........................................................................ 11 History & Context: Introduction........................................................................................ 14 Map of South Africa............................................................................ 15 Xhosa Tribe......................................................................................... -

Political Shifts and Black Theatre in South Africa Rangoajane, F.L

Political shifts and black theatre in South Africa Rangoajane, F.L. Citation Rangoajane, F. L. (2011, November 16). Political shifts and black theatre in South Africa. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18077 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18077 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Political Shifts and Black Theatre in South Africa PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 16 november 2011 klokke 11.15 uur door Francis L. Rangoajane geboren te Bloemfontein, Zuid-Afrika in 1963 Promotiecommissie Promotor Prof.dr. E.J. van Alphen Co-promotor Dr. D. Merolla Leden Prof.dr. M.E. de Bruijn Dr. Y. Horsman Prof.dr. E. Jansen (Universiteit van Amsterdam) Prof.dr. R.J. Ross Prof.dr. W.J.J. Schipper-de Leeuw Table of Contents Introduction 1 1.1 The Creation of Apartheid South Africa 5 1.2 Black Theatre in Apartheid South Africa 8 1.3 Challenges 15 1.4 Experimenting in Black Theatre 25 1.5 Research Method 27 1.6 Thesis Approach 28 1.7 Selection Criteria 30 1.8 Data Analysis and Interpretation 35 1.9 Chapter Layout 36 1 The South African State and Black Theatre 38 1.1 Apartheid and Black Theatre 38 1.2.1 Gibson Kente’s Too Late 46 1.2.2 Kani, Ntshona -

Regarding Westernization in Central Africa: Hybridity in the Works Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Regarding Westernization in Central Africa: Hybridity in the Works of Three Chadian Playwrights Enoch Reounodji Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reounodji, Enoch, "Regarding Westernization in Central Africa: Hybridity in the Works of Three Chadian Playwrights" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2893. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2893 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REGARDING WESTERNIZATION IN CENTRAL AFRICA: HYBRIDITY IN THE WORKS OF THREE CHADIAN PLAYWRIGHTS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Theatre By Enoch Reounodji B.A., University of Chad (Chad), 1991 M.A., University of Maiduguri (Nigeria), 1999 August 2011 Dedication For Trophine, Gracie, and Gloria: my warmth, my world, my life. In loving memory of my mother and father: “the dead are not dead.” ii Acknowledgments This dissertation represents a long journey marked by setbacks and successes. It has been a collaborative endeavor. Many people have contributed toward the completion of this work, which is a huge accomplishment for my academic life, my family, and my entire community. -

When Granny Went on the Internet: the Screenplay and the Search for Content and Tone in South African Screenwriting

When Granny Went on the Internet: The Screenplay and the Search for Content and Tone in South African Screenwriting by Carolyn Burnett Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree PhD in Media and Digital Arts in the Graduate Programme in the College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. August, 2014 ABSTRACT The development of content and the creation of tone in a screenplay is a challenging task for the screenwriter. This thesis explores, through the writing of an original screenplay, how content is sourced and tone is manipulated in a comic story. The context of screenwriting in South Africa is established and an account is given of the emerging micro-budget filmmaking movement along with a discussion of issues relating to the broadband streaming of films in South Africa. Such factors, along with declining or stagnating cinema attendance, affect how films will be viewed and distributed in South Africa. A major case study was conducted on the South African film Jozi (2010) by director-screenwriter Craig Freimond. The influences, screenwriting process, sources of content and creation of tone in his film are examined through in- depth interviews and structural, thematic and tonal analysis of his work. An original feature-length screenplay, When Granny Went on the Internet (2013), was written. An account is offered of how the content was derived and tone was manipulated. A reflective report of the screenwriting process offers insight into the development of the multi-layered, tonally complex comic screenplay and suggests that a new form of South African comedy may be emerging. -

Responses to the Film

Heroines, Victims and Survivors: Female Minors as Active Agents in Films about African Colonial and Postcolonial Conflicts. by Norita Mdege Town Thesis Presented forCape the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Film Studies in the Centre for Filmof and Media Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN September 2017 Supervisor:University Associate Professor Martin Botha The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract This thesis analyses the representations of girls as active agents in fictional films about African colonial and postcolonial conflicts. Representations of these girls are located within local and global contexts, and viewed through an intersectional lens that sees girls as trebly marginalised as “female,” “child soldiers” and “African.” A cultural approach that combines textual and contextual analyses is used to draw links between the case study films and the societies within which they are produced and consumed. The thesis notes the shift that occurs between the representations of girls in anti-colonial struggles and postcolonial wars as a demonstration of ideological underpinnings that link these representations to their socio- political contexts. For films about African anti-colonial conflicts, the author looks at Sarafina! (Darrell Roodt, 1992) and Flame (Ingrid Sinclair, 1996). Representations in the optimistic Sarafina! are used to mark a trajectory that leads to the representations in Flame, which is characterised by postcolonial disillusionment. -

Disney's the Lion King

M AY 7 – JUNE 2 .375” IMAGE AREA IMAGE .375” © Disney 3 NASHVILLE / C M Y K 7.125” X 10.875” 89420 / FRONT COVER / PLAYBILL MAGAZINE Pictured from left to right: Scott Walker Jarrod Grubb Lori M. Carver Rita Mitchell Laura Folk Renee Chevalier Steve Scott CFP®, Vice President Vice President CFP®, ChFC®, Senior Vice Senior Vice Vice President Vice President Relationship Relationship Vice President, President President Relationship Relationship Manager Manager Horizon Wealth Private Client Medical Private Manager Manager Advisory Services Banking A TEAM APPROACH TO FINANCIAL SUCCESS Personal Advantage Banking from First Tennessee. A distinguished level of banking designed specifically for those with exclusive financial needs. After all, you’ve been vigilant in acquiring a certain level of wealth, and we’re just as vigilant in finding sophisticated ways to help you achieve an even stronger financial future. While delivering personal, day-to-day service focused on intricate details, your Private Client Relationship Manager will also assemble a team of CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNERTM professionals with objective advice, investment officers, and retirement specialists that meet your complex needs for the future. TO START EXPERIENCING THE EXCLUSIVE SERVICE YOU’VE EARNED, CALL 615-734-6165 Investments: Not A Deposit Not Guaranteed By The Bank Or Its Affiliates Not FDIC Insured Not Insured By Any Federal Government Agency May Go Down In Value Financial planning provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association (FTB). Investments available through First Tennessee Brokerage, Inc., member FINRA, SIPC, and a subsidiary of FTB. Banking products and services provided by First Tennessee Bank National Association. Member FDIC. -

Production Notes

Production Notes Department of Trade and Industry M-Net And Dual Films In association with The KwaZulu-Natal Film Commission and National Film and Video Foundation And Afrika Productions Trust Funded By the National Lotteries Commission Present A Committed Artists Production In association with Indigenous Film An Mbongeni Ngema Film ASINAMALI Danica De La Rey Boitumelo Shisana Luzuko Nqeto Tertius MeintJes Sbu Ngema Gerard Rudolf Dikeledi LeteBele Sibusiso Kotelo BhekithemBa Zwane Moses Mahlangu Congo Hadebe Kere Nyawo And Mbongeni Ngema as “Comrade” Written, Produced and Directed By MBONGENI NGEMA Executive Producer DAVID DISON Producers CHRISTIANNE BENNETTO DARRELL ROODT Associate Producers HELEN KUUN THANDEKILE MQADI AFRIKA NGEMA BRIONY HORWITZ MWELI MZIZI HARRY HOFMEYR TARIKU BOGALE Director of Photography DINO BENEDETTI Production Designer SAMANTHA LOTTER DELL Costume Designer ANDREW PHIRI Make Up and Hair Designer ANGELINE BOSHOFF Choreographers NOMPUMELELO GUMEDE NGEMA DAVID MATAMELA VUSI MAJOLA Synopsis One of South Africa’s greatest classic theatre productions, Asinamali has been immortalised in film. The story follows Comrade Washington (Mbongeni Ngema) who returns to South Africa in 1986 to create a prison theatre project. Washington believes in the power of music and theatre to transform the lives of people: the political activists, the criminals and offenders who find themselves incarcerated He guides the inmates, silenced by the brutal prison authorities, as well as their sadistic, ruthless warden Sergeant Mgwaqaza (Boitumelo Chuck Shisana) to act and sing out the stories of their lives. The tale has its roots in the height of the rent boycotts of the 1980s. In Durban’s oldest township of Lamontville, a community leader called Msizi Dube rose up and launched a campaign under the slogan ‘Asinamali’ (we have no money).