Black Theatre Movement PREPRINT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

13 First Published in Southafrica in 2012 by Jacana Media As Thieves at the Dinner Table: Enforcing the Competition Act All Rights Reserved

Enforcing Competition Rules in South Africa To Terry (like I mean it) Enforcing Competition Rules in South Africa Thieves at the Dinner Table David Lewis Executive Director,Corruption Watch and Extraordinary Professor,Gordon Institute of Business Science, South Africa Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA International Development Research Centre Ottawa + Cairo + Montevideo + Nairobi + New Delhi © International Development Research Centre 2013 First published in SouthAfrica in 2012 by Jacana Media as Thieves at the Dinner Table: Enforcing the Competition Act All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500 Ottawa, ON, K1G 3H9 Canada www.idrc.ca / [email protected] ISBN 978 1 55250 550 2 (IDRC e-book) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2012950432 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Law Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78195 375 4 ISBN 978 1 78195 374 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound by MPG Books Group, UK Contents Preface vi 1. Beginnings 1 2. The new competition regime 24 3. Mergers 70 4. Abuse of dominance 130 5. Cartels 191 6. Competition enforcement on the world stage 228 7. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Making memory work: Performing and inscribing HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa Thesis How to cite: Doubt, Jenny Suzanne (2014). Making memory work: Performing and inscribing HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000eef6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Making Memory Work: Performing and Inscribing HIV I AIDS in Post-Apartheid South Africa Jenny Suzanne Doubt (BA, MA) Submitted towards a PhD in English Literature at the Open University 5 July 2013 1)f\"'re:. CC ::;'.H':I\\\!:;.SIOfl: -::\ ·J~)L'I ..z.t.... L~ Vt',':·(::. 'J\:. I»_",i'~,' -: 21 1'~\t1~)<'·i :.',:'\'t- IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk PAGE NUMBERING AS ORIGINAL Jenny Doubt Making Memory Work: Performing and Inscribing HIV/AIDS in Post-Apartheid South Africa Submitted towards a PhD in English Literature at the Open University 5 July 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that the cultural practices and productions associated with HIV/AIDS represent a major resource in the struggle to understand and combat the epidemic. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

070914Land-Panelreport.Pdf

REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS BY THE PANEL OF EXPERTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF POLICY REGARDING LAND OWNERSHIP BY FOREIGNERS IN SOUTH AFRICA PRESENTED TO THE MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE AND LAND AFFAIRS, HON. LULU XINGWANA Panel Members: Prof. Shadrack Gutto (Chairperson), Dr Joe Matthews (Deputy Chairperson) Prof. Fred Hendricks, Mr. Bonile Jack, Prof. Dirk Kotzé, Mr. Mandla Mabuza, Ms Nothemba Rossette Mlozi, Ms Mandisa Monokali, Mr Cecil Morden, Ms Christine Qunta Departmental technical support team: Mr Jeff Sebape, Ms Tumi Seboka, Mr Sunday Ogunronbi, Mr Sam Lefafa Dr Sipho M D Sibanda, Dr Kwandi K M Kondlo, Mr Ndiphiwe Ngewu Pretoria, City of Tshwane, August 007 PLOF REPORT TABLE OF CONTENT Acknowledgements Introduction and Terms of Reference Structure of the Report Section 1: Executive Summary Section 2: Analysis and Recommendations Part 1: Analysis of written public submissions, oral representations, recommendation by the parliamentary committee, and relevant National Land Summit resolutions Part 2: Patterns of land ownership in South Africa – quantification and spatial mapping Part 3: International practices and policies: Regulation of ownership and use of land and property by foreigners in other countries Part 4: Revision, harmonization and rationalization of legislation regulating development planning and land use Part 5: Recommendations Section 3: Appendices (This section will be published separately from the main report.) 1 – Definition of key terms and concepts – List of those who made written submissions to the Panel – List of those who made written submissions [duplication of ?] 4 – Opening statement at the public hearings 5 – Selected treaties and trade agreements 6 – Report on policies and regulations in other countries 7 – Analysis of land enactments by Qunta Incorporated Attorneys & Conveyances 8 – DPLG Rationalisation Report: Review of legislation affecting Local Government, April 00. -

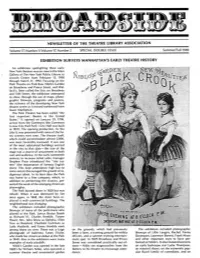

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

Special Issue 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571

BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science An Online, Peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal Vol: 2 Special Issue: 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 UGC approved Journal (J. No. 44274) CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in | www.bodhijournals.com BODHI BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science (ISSN: 2456-5571) is online, peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal, which is powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services, (CRRPS) India. It is committed to bring together academicians, research scholars and students from all over the world who work professionally to upgrade status of academic career and society by their ideas and aims to promote interdisciplinary studies in the fields of humanities, arts and science. The journal welcomes publications of quality papers on research in humanities, arts, science. agriculture, anthropology, education, geography, advertising, botany, business studies, chemistry, commerce, computer science, communication studies, criminology, cross cultural studies, demography, development studies, geography, library science, methodology, management studies, earth sciences, economics, bioscience, entrepreneurship, fisheries, history, information science & technology, law, life sciences, logistics and performing arts (music, theatre & dance), religious studies, visual arts, women studies, physics, fine art, microbiology, physical education, public administration, philosophy, political sciences, psychology, population studies, social science, sociology, social welfare, linguistics, literature and so on. Research should be at the core and must be instrumental in generating a major interface with the academic world. It must provide a new theoretical frame work that enable reassessment and refinement of current practices and thinking. This may result in a fundamental discovery and an extension of the knowledge acquired. -

2016 IGNITION Festival Release 2016

Press contact: Cathy Taylor/Kelsey Moorhouse Cathy Taylor Public Relations [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 773-564-9564 Victory Gardens Theater Announces Lineup for 2016 IGNITION Festival of New Plays 2016 Festival runs August 5–7, 2016 CHICAGO, IL – Victory Gardens Theater announces the lineup for the 2016 IGNITION Festival of New Plays, including The Wayward Bunny by Greg Kotis; BREACH: a manifesto on race in America through the eyes of a black girl recovering from self-hate by Antoinette Nwandu; EOM (end of message) by Laura Jacqmin; Kill Move Paradise by James Ijames; Gaza Rehearsal by Karen Hartman; and Girls In Cars Underwater by Tegan McLeod. The 2016 Festival runs August 5-7, 2016 at Victory Gardens Theater, located at 2433 N Lincoln Avenue. INGITION’s six selected plays will be presented in a festival of readings and will be directed by leading artists from Chicago. Following the readings, two of the plays may be selected for intensive workshops during Victory Gardens’ 2016-17 season, and Victory Gardens may produce one of these final scripts in an upcoming season. "At Victory Gardens Theater, we bridge Chicago communities through innovative and challenging new plays by giving established and emerging playwrights the time and space to develop their work. This year, we have invited some of the most thrilling playwrights to join our IGNITION Festival,” said Isaac Gomez, Victory Gardens Theater Literary Manager. “Their plays exemplify the current political and cultural zeitgeist of our city and country: the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, race and gender, the modern struggles of fatherhood, the insular world and morality of video gaming, and a woman’s journey to self-love. -

Reading and Writing As Transformative Action in Maria Irene Fornes’ and Adrienne Kennedy’S Plays

READING AND WRITING AS TRANSFORMATIVE ACTION IN MARIA IRENE FORNES’ AND ADRIENNE KENNEDY’S PLAYS by Insoo Lee B.A. in English Literature, Seoul National University, 1995 B.F.A.in Playwriting, Korea National University of Arts, 2001 M.A. in Theatre Art, Miami University, Ohio, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Dietrich School of Arts and Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCE This dissertation was presented by Insoo Lee It was defended on April 16, 2012 and approved by Kathleen E. George, PhD, Professor Attilio Favorini, PhD, Professor Bruce McConachie, PhD, Professor Susan Z. Andrade, PhD, Associate Professor Dissertation Advisor: Kathleen E. George, PhD, Professor ii Copyright © by Insoo Lee 2012 iii READING AND WRITING AS TRANSFORMATIVE ACTION IN MARIA IRENE FORNES’ AND ADRIENNE KENNEDY’S PLAYS Insoo Lee, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This dissertation examines Maria Irene Fornes’ and Adrienne Kennedy’s plays, focusing on the female characters’ act of reading and writing on stage. Usually, reading and writing on stage are considered to be passive and static, but in the two playwrights’ works, they are used as an effective plot device that moves the drama forward and as willful efforts by the female characters to develop their sense of identities. Furthermore, in contrast to the usual perception of reading and writing as intellectual processes, Fornes and Kennedy depict these acts as intensely physical and sensual. Julia Kristeva’s and Hélène Cixous’ poststructuralist psychoanalytic theories of language and female sexuality, and Gloria Anzaldúa’s theory of writing the body are the major theoretical framework within which I explore the two playwrights’ works. -

Lloyd Richards in Rehearsal

Lloyd Richards in Rehearsal by Everett C. Dixon A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Theatre Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario September 2013 © Everett Dixon, September 2013 Abstract This dissertation analyzes the rehearsal process of Caribbean-Canadian-American director Lloyd Richards (1919-2006), drawing on fifty original interviews conducted with Richards' artistic colleagues from all periods of his directing career, as well as on archival materials such as video-recordings, print and recorded interviews, performance reviews and unpublished letters and workshop notes. In order to frame this analysis, the dissertation will use Russian directing concepts of character, event and action to show how African American theatre traditions can be reformulated as directing strategies, thus suggesting the existence of a particularly African American directing methodology. The main analytical tool of the dissertation will be Stanislavsky's concept of "super-super objective," translated here as "larger thematic action," understood as an aesthetic ideal formulated as a call to action. The ultimate goal of the dissertation will be to come to an approximate formulation of Richards' "larger thematic action." Some of the artists interviewed are: Michael Schultz, Douglas Turner Ward, Woodie King, Jr., Dwight Andrews, Stephen Henderson, Thomas Richards, Scott Richards, James Earl Jones, Charles S. Dutton, Courtney B. Vance, Michele Shay, Ella Joyce, and others. Keywords: action, black aesthetics, black theatre movement, character, Dutton (Charles S.), event, Hansberry (Lorraine), Henderson (Stephen M.), Molette (Carlton W. and Barbara J.), Richards (Lloyd), Richards (Scott), Richards (Thomas), Jones (James Earl), Joyce (Ella), Vance (Courtney ii B.), Schultz (Michael), Shay (Michele), Stanislavsky (Konstantin), super-objective, theatre, Ward (Douglas Turner), Wilson (August). -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 1 (2018) The Affective Aesthetics of Transnational Feminism Silvia Schultermandl, Katharina Gerund, and Anja Mrak ABSTRACT: This review essay offers a consideration of affect and aesthetics in transnational feminism writing. We first discuss the general marginalization of aesthetics in selected canonical texts of transnational feminist theory, seen mostly as the exclusion of texts that do not adhere to the established tenets of academic writing, as well as the lack of interest in the closer examination of the features of transnational feminist aesthetic and its political dimensions. In proposing a more comprehensive alternative, we draw on the current “re-turn towards aesthetics” and especially on Rita Felski’s work in this context. This approach works against a “hermeneutics of suspicion” in literary analyses and re-directs scholarly attention from the hidden messages and political contexts of a literary work to its aesthetic qualities and distinctly literary properties. While proponents of these movements are not necessarily interested in the political potential of their theories, scholars in transnational feminism like Samantha Pinto have shown the congruency of aesthetic and political interests in the study of literary texts. Extending Felski’s and Pinto’s respective projects into an approach to literary aesthetics more oriented toward transnational feminism on the one hand and less exclusively interested in formalist experimentation on the other, we propose the concept of affective aesthetics. It productively complicates recent theories of literary aesthetics and makes them applicable to a diverse range of texts. We exemplarily consider the affective dimensions of aesthetic strategies in works by Christina Sharpe, Sara Ahmed, bell hooks, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who promote the idea of feminism as an everyday practice through aesthetically rendered texts that foster a personal and intimate link between the writer, text, and the reader.