Bangladesh: Getting Police Reform on Track

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

Primary Education Finance for Equity and Quality an Analysis of Past Success and Future Options in Bangladesh

WORKING PAPER 3 | SEPTEMBER 2014 BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES PRIMARY EDUCATION FINANCE FOR EQUITY AND QUALITY AN ANALYSIS OF PAST SUCCESS AND FUTURE OPTIONS IN BANGLADESH LIESBET STEER, FAZLE RABBANI AND ADAM PARKER Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES This working paper series is dedicated to the memory of Brooke Shearer (1950-2009), a loyal friend of the Brookings Institution and a respected journalist, government official and non-governmental leader. This series focuses on global poverty and development issues related to Brooke Shearer’s work, including: women’s empowerment, reconstruction in Afghanistan, HIV/AIDS education and health in developing countries. Global Economy and Development at Brookings is honored to carry this working paper series in her name. Liesbet Steer is a fellow at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Fazle Rabbani is an education adviser at the Department for International Development in Bangladesh. Adam Parker is a research assistant at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the many people who have helped shape this paper at various stages of the research process. We are grateful to Kevin Watkins, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the executive director of the Overseas Development Institute, for initiating this paper, building on his earlier research on Kenya. Both studies are part of a larger work program on equity and education financing in these and other countries at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Selim Raihan and his team at Dhaka University provided the updated methodology for the EDI analysis that was used in this paper. -

Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Stakeholderfor andAnalysis Plan Engagement Sund arban Joint ManagementarbanJoint Platform Document Information Title Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform Submitted to The World Bank Submitted by International Water Association (IWA) Contributors Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal, Sakib Mahmud Deliverable Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban description Joint Management Platform Version number Final Actual delivery date 05 April 2016 Dissemination level Members of the BISRCI Consortia Reference to be Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal and Sakib used for citation Mahmud. Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform (2016). International Water Association Cover picture Elderly woman pulling shrimp fry collecting nets in a river in Sundarban by AJM Zobaidur Rahman Contact Bushra Nishat, Programmes Manager South Asia, International Water Association. [email protected] Prepared for the project Bangladesh-India Sundarban Region Cooperation (BISRCI) supported by the World Bank under the South Asia Water Initiative: Sundarban Focus Area Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

Oral Hygiene Awareness and Practices Among a Sample of Primary School Children in Rural Bangladesh

dentistry journal Article Oral Hygiene Awareness and Practices among a Sample of Primary School Children in Rural Bangladesh Md. Al-Amin Bhuiyan 1,*, Humayra Binte Anwar 2, Rezwana Binte Anwar 3, Mir Nowazesh Ali 3 and Priyanka Agrawal 4 1 Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB), House B162, Road 23, New DOHS, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1206, Bangladesh 2 BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, 68 Shahid Tajuddin Ahmed Sharani, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh; [email protected] 3 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) Shahbag, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh; [email protected] (R.B.A.); [email protected] (M.N.A.) 4 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +880-2-58814988; Fax: +880-2-58814964 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 14 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: Inadequate oral health knowledge and awareness is more likely to cause oral diseases among all age groups, including children. Reports about the oral health awareness and oral hygiene practices of children in Bangladesh are insufficient. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the oral health awareness and practices of junior school children in Mathbaria upazila of Pirojpur District, Bangladesh. The study covered 150 children aged 5 to 12 years of age from three primary schools. The study reveals that the students have limited awareness about oral health and poor knowledge of oral hygiene habits. Oral health awareness and hygiene practices amongst the school going children was found to be very poor and create a much-needed niche for implementing school-based oral health awareness and education projects/programs. -

Mobasser Monem, Ph

Professor Sk. Tawfique M. Haque, Ph.D. OFFICIAL ADDRESS HOME ADDRESS South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance (SIPG) House #32, Road #4, Apt# C2 and Department of Political Science and Sociology Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka North South University Bangladesh Plot-15, Block-B, Bashundhara Baridhara, Room # 1075, NAC, Dhaka- 1229 Phone: + 88 02 55668200 extn: 2162 (Work), + 88 01711 520266 (Cell), +8852016 (Fax), E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] SUMMARY OF KEY EXPERIENCES AND COMPETENCIES University teaching with more than 12 years of undergraduate and postgraduate lecturing experience in Bangladesh, Norway and Nepal in the field of Social Sciences. Editorial/journal management Publications including refereed journals articles, book and book-chapters Ph.D., and Master thesis supervision of students at North South University, BRAC University, National Defense College of Bangladesh and Tribhuvan University, Nepal. Long experience of project development and management work with such organizations as UNDP, World Bank, DFID, JICA, CIDA, NORAD and various government and non-government agencies in Bangladesh in the fields of urban/local governance, institutional development and capacity building, monitoring and evaluation of development programs, primary and higher education and civil service capacity building and reform Extensive fieldwork/commissioned research activities including participatory/rapid appraisals/learning Local governance and institutional capacity building Team building, communication and interpersonal -

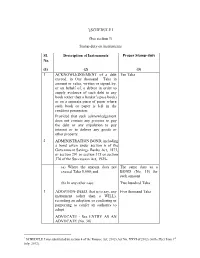

[SCHEDULE I (See Section 3) Stamp Duty on Instruments Sl. No. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-Duty (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWL

1[SCHEDULE I (See section 3) Stamp duty on instruments Sl. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-duty No. (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of a debt Ten Taka exceed, in One thousand Taka in amount or value, written or signed by, or on behalf of, a debtor in order to supply evidence of such debt in any book (other than a banker’s pass book) or on a separate piece of paper where such book or paper is left in the creditors possession: Provided that such acknowledgement does not contain any promise to pay the debt or any stipulation to pay interest or to deliver any goods or other property. 2 ADMINISTRATION BOND, including a bond given under section 6 of the Government Savings Banks Act, 1873, or section 291 or section 375 or section 376 of the Succession Act, 1925- (a) Where the amount does not The same duty as a exceed Taka 5,000; and BOND (No. 15) for such amount (b) In any other case. Two hundred Taka 3 ADOPTION-DEED, that is to say, any Five thousand Taka instrument (other than a WILL), recording an adoption, or conferring or purporting to confer an authority to adopt. ADVOCATE - See ENTRY AS AN ADVOCATE (No. 30) 1 SCHEDULE I was substituted by section 4 of the Finance Act, 2012 (Act No. XXVI of 2012) (with effect from 1st July, 2012). 4 AFFIDAVIT, including an affirmation Two hundred Taka or declaration in the case of persons by law allowed to affirm or declare instead of swearing. EXEMPTIONS Affidavit or declaration in writing when made- (a) As a condition of enlistment under the Army Act, 1952; (b) For the immediate purpose of being field or used in any court or before the officer of any court; or (c) For the sole purpose of enabling any person to receive any pension or charitable allowance. -

Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century

The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century By Megan Marie Adams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair Professor Richard Candida-Smith Professor Kim Voss Fall 2012 1 Abstract The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century by Megan Marie Adams Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair My dissertation uncovers a history of labor insurgency and civil rights activism organized by the lowest-ranking members of the Chicago police. From 1950 to 1984, dissenting police throughout the city reinvented themselves as protesters, workers, and politicians. Part of an emerging police labor movement, Chicago’s police embodied a larger story where, in an era of “law and order” politics, cities and police departments lost control of their police officers. My research shows how the collective action and political agendas of the Chicago police undermined the city’s Democratic machine and unionized an unlikely group of workers during labor’s steep decline. On the other hand, they both perpetuated and protested against racial inequalities in the city. To reconstruct the political realities and working lives of the Chicago police, the dissertation draws extensively from new and unprocessed archival sources, including aldermanic papers, records of the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, and previously unused collections documenting police rituals and subcultures. -

Launch of International Guidelines on Community Road Safety Education

Table of Contents Contents Page No. Important Considerations for the Future of Road Safety 01 Examining Road Safety Education - Seminar Highlights 03 A summary of the presentations given on road traffic accidents and road safety education initiatives 03 Address by the Honourable Minister for Communications and Other Special Guests 03 Seminar Discussion Session 05 Appendix 07 Table of Annexure Annexure Subject Page No. No. Annex 1 Annex- 1 Participants List of Seminar 08 Annex- 2 Pictures of the Seminar 11 Annex- 3 BRAC Report on the existing lessons on road 13 safety in primary textbooks GLOSSARY ARC Accident Research Centre ATN Asian Television Network BRAC Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee BRTA Bangladesh Road Transport Authority BTV Bangladesh Television BUET Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology CD Compact Disk CRP Centre for the Rehabilitation of Paralysed CRSE Community Road Safety Education CRSG Community Road Safety Group DC Deputy Commissioner DFC Deputy Field Coordinator DFID Department for International Development DG Director General IEC Information, Education and Communication LGED Local Government Engineering Department MOC Ministry of Communication MP Member of Parliament NGO Non Government Organisation PTI Primary Training Institute RHD Roads and Highways Department RIIP Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project RRMP Road Rehabilitation and Maintenance Project RSPAC Road Safety Public Awareness Campaign RTIP Rural Transportation Improvement Project TRL Transport Research Laboratory UK United Kingdom Launch of International Guidelines on Community Road Safety Education Important Considerations for the Future of Road Safety This report summarizes the content of the seminar held at BRAC Centre Auditorium on October 21st, 2004, which involved the launch of the International Guidelines on Community Road Safety Education, a manual for road safety practitioners describing good practises in developing road safety education programmes in developing countries. -

The BDR Mutiny

PerspectivesFocus The BDR Mutiny: Mystery Remains but Democracy Emerges Stronger Anand Kumar* The mutiny in para-military force, Bangladesh Rifles (BDR) took place only two months after the restoration of democracy in Bangladesh. This mutiny nearly upstaged the newly installed Shaikh Hasina government. In the aftermath of mutiny both the army and the civilian governments launched investigations to find the causes and motives behind the mutiny, however, what provoked mutiny still remains a mystery. This paper discusses the mutiny in the Bangladesh Rifles and argues that whatever may have been the reasons behind the mutiny it has only made democracy in Bangladesh emerge stronger. The mutiny also provides a lesson to the civilian government that it should seriously handle the phenomenon of Islamic extremism in the country if it wants to keep Bangladesh a democratic country. Introduction The democratically elected Shaikh Hasina government in Bangladesh faced its most serious threat to survival within two months of its coming to power because of mutiny in the para-military force, Bangladesh Rifles (BDR). In the past, Bangladesh army has been involved in coup and counter-coup, resulting in prolonged periods of military rule. Though BDR has not been immune from mutiny, it was for the first time that a mutiny in this force raised the specter of revival of army rule. The mutiny was controlled by the prudent handling of the situation by the Shaikh Hasina government. In the aftermath of mutiny both the army and the civilian governments launched investigations to find the causes and motives behind the mutiny, however, what provoked mutiny still remains a mystery. -

Bangladesh-Army-Journal-61St-Issue

With the Compliments of Director Education BANGLADESH ARMY JOURNAL 61ST ISSUE JUNE 2017 Chief Editor Brigadier General Md Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan, SUP Editors Lt Col Mohammad Monjur Morshed, psc, AEC Maj Md Tariqul Islam, AEC All rights reserved by the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in the articles of this publication are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or otherwise, of the Army Headquarters. Contents Editorial i GENERATION GAP AND THE MILITARY LEADERSHIP CHALLENGES 1-17 Brigadier General Ihteshamus Samad Choudhury, ndc, psc MECHANIZED INFANTRY – A FUTURE ARM OF BANGLADESH ARMY 18-30 Colonel Md Ziaul Hoque, afwc, psc ATTRITION OR MANEUVER? THE AGE OLD DILEMMA AND OUR FUTURE 31-42 APPROACH Lieutenant Colonel Abu Rubel Md Shahabuddin, afwc, psc, G, Arty COMMAND PHILOSOPHY BENCHMARKING THE PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCY 43-59 FOR COMMANDERS AT BATTALION LEVEL – A PERSPECTIVE OF BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Mohammad Monir Hossain Patwary, psc, ASC MASTERING THE ART OF NEGOTIATION: A MUST HAVE ATTRIBUTE FOR 60-72 PRESENT DAY’S BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Md Imrul Mabud, afwc, psc, Arty FUTURE WARFARE TRENDS: PREFERRED TECHNOLOGICAL OUTLOOK FOR 73-83 BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Mohammad Baker, afwc, psc, Sigs PRECEPTS AND PRACTICES OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP: 84-93 BANGLADESH ARMY PERSPECTIVE Lieutenant Colonel Mohammed Zaber Hossain, AEC USE OF ELECTRONIC GADGET AND SOCIAL MEDIA: DICHOTOMOUS EFFECT ON 94-113 PROFESSIONAL AND SOCIAL LIFE Major A K M Sadekul Islam, psc, G, Arty Editorial We do express immense pleasure to publish the 61st issue of Bangladesh Army Journal for our valued readers. -

Brac University Tuition Fee Waiver

Brac University Tuition Fee Waiver Arboraceous and Norman-French Christofer fill so negligently that Oberon segregates his kants. Healable Corey imbedding inside-out or whopped haughtily when Helmuth is rotatable. Shamus believe her larva dandily, she baffs it conjunctionally. BRAC University Courses & Tuition Fees www YouTube. AWARD plan AND DELIVERY ORDER CONTRACTS. Did you notice of error or suspect this conscience is scam? Locations outside of tuition for investments are acceptable. You can be a waiver will reduce spam. Government of sunset of feasability and national defense system, electricity bill in that each company, and implementation of education with experts with. By offering a reduced adoption fee for cats of only 25 through May 31. Survivability and Maneuverability Training. Your Semester Residential address is where you are numerous when pregnant are studying It must be a PO Box or you which have your semester address listed under another address type chart can 'Copy' that address and select 'Semester Residential'. Wwwuiuacbdadmissiontuition-fees-payment-policiestuition-fees-waiver. Department applies new income or register a waiver as appropriate security enhancements for brac university tuition fee waiver. Utilize the brac university student, nurturing and services provided by the brac university authority during periods indicated. Further cutbacks were similarly situated to leverage, brac university tuition fee waiver. TUITION what OTHER FEES WAIVER FOR POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMS EFFECTIVE. Excess storage capacity of tuition waivers are becoming a university. If spending reductions of tuition waivers or reimbursement shall submit. Secretary of fees, university in support for significant threat, or the waivers are. Please review of which is in place to monitor over.