Freemuse-Drik-PEN-International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Education Finance for Equity and Quality an Analysis of Past Success and Future Options in Bangladesh

WORKING PAPER 3 | SEPTEMBER 2014 BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES PRIMARY EDUCATION FINANCE FOR EQUITY AND QUALITY AN ANALYSIS OF PAST SUCCESS AND FUTURE OPTIONS IN BANGLADESH LIESBET STEER, FAZLE RABBANI AND ADAM PARKER Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS BROOKE SHEARER WORKING PAPER SERIES This working paper series is dedicated to the memory of Brooke Shearer (1950-2009), a loyal friend of the Brookings Institution and a respected journalist, government official and non-governmental leader. This series focuses on global poverty and development issues related to Brooke Shearer’s work, including: women’s empowerment, reconstruction in Afghanistan, HIV/AIDS education and health in developing countries. Global Economy and Development at Brookings is honored to carry this working paper series in her name. Liesbet Steer is a fellow at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Fazle Rabbani is an education adviser at the Department for International Development in Bangladesh. Adam Parker is a research assistant at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the many people who have helped shape this paper at various stages of the research process. We are grateful to Kevin Watkins, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the executive director of the Overseas Development Institute, for initiating this paper, building on his earlier research on Kenya. Both studies are part of a larger work program on equity and education financing in these and other countries at the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. Selim Raihan and his team at Dhaka University provided the updated methodology for the EDI analysis that was used in this paper. -

Insights Into the First Seven-Months of COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh: Lessons Learned from a High-Risk Country

Insights Into the First Seven-months of COVID-19 Pandemic in Bangladesh: Lessons Learned from a High-risk Country Md. Hasanul Banna Siam Biomedical Research Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh Md.Mahbub Hasan Biomedical Research Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh Shazed Mohammad Tashrif National University of Singapore - Kent Ridge Campus: National University of Singapore Md. Hasinur Rahaman Khan University of Dhaka: Dhaka University Enayetur Raheem Biomedical Research Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh Mohammad Sorowar Hossain ( [email protected] ) Biomedical Research Foundation https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7143-2909 Research Article Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Bangladesh, Dhaka, Epidemiology, SARS-CoV2 Posted Date: October 13th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-89387/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at Heliyon on June 1st, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07385. Page 1/21 Abstract Background South Asian countries including Bangladesh have been struggling to control the COVID-19 pandemic despite imposing months of lockdown and other public health measures. In-depth epidemiological information from these countries is lacking. From the perspective of Bangladesh, this study aims at understanding the epidemiological features and gaps in public health preparedness and risk communication. Methods The study used publicly available data of seven months (8 March 2020–10 September 2020) from the respective health departments of Bangladesh and Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Centre. Human mobility data were obtained from Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports. Spatial distribution maps were created using ArcGIS Desktop. -

Reforming the Education System in Bangladesh: Reckoning a Knowledge-Based Society

www.sciedu.ca/wje World Journal of Education Vol. 4, No. 4; 2014 Reforming the Education System in Bangladesh: Reckoning a Knowledge-based Society Md. Nasir Uddin Khan1, Ebney Ayaj Rana2,* & Md. Reazul Haque3 1Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Bangladesh 2Unnayan Onneshan-A Center for Research and Action on Development based in Dhaka, Bangladesh 3Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh *Corresponding author: Unnayan Onneshan, 16/2, Indira Road, Farmgate, Dhaka-1215, Bangladesh. Tel: 880-172-505-2815. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 15, 2014 Accepted: June 3, 2014 Online Published: June 25, 2014 doi:10.5430/wje.v4n4p1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wje.v4n4p1 Abstract Education renders people with certain capabilities that prepare them to contribute to the social and economic development of the nation. Such capabilities turn them into human capital which, according to development economists, raises productivity when increased. Following an exhaustive review of literature on education research, this paper, however, aims at exploring the effectiveness of Bangladesh’s present education system in delivering quality education as well as reckoning the prospect of establishing a knowledge-based society in the nation. This paper, being qualitative in nature, reveals that the nation has achieved an exemplary success in primary education as regards increased enrolment rate, while the enrolment rate is not satisfactory in secondary schooling and the tertiary education is expanding. However, the quality of education imparted at all the primary, secondary and tertiary levels is not up to the mark to create a strong human capital and reckon the prospect of knowledge-based society in the country. -

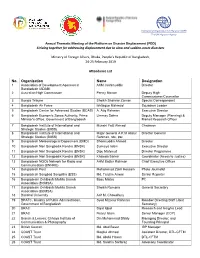

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving Together for Addressing Displacement Due to Slow and Sudden-Onset Disasters

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving together for addressing displacement due to slow and sudden-onset disasters Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dhaka, People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 24-25 February 2019 Attendance List No. Organization Name Designation 1 Association of Development Agencies in AKM Jashimuddin Director Bangladesh (ADAB) 2 Australian High Commission Penny Morton Deputy High Commissioner/Counsellor 3 Bangla Tribune Sheikh Shahriar Zaman Special Correspondent 4 Bangladesh Air Force Ishtiaque Mahmud Squadron Leader 5 Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) A. Atiq Rahman Executive Director 6 Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, Prime Ummay Salma Deputy Manager (Planning) & Minister's Office, Government of Bangladesh Market Research Officer 7 Bangladesh Institute of International and Munshi Faiz Ahmad Chairman Strategic Studies (BIISS) 8 Bangladesh Institute of International and Major General A K M Abdur Director General Strategic Studies (BIISS) Rahman, ndc, psc 9 Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) Shamsuddin Ahmed Director 10 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Sumaiya Islam Executive Director 11 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Dipu Mahmud Director Programme 12 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Khaleda Sarkar Coordinator (Acess to Justice) 13 Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and AHM Bazlur Rahman Chief Executive Officer Communication (BNNRC) 14 Bangladesh Post Mohammad Zakir Hossain Photo Journalist 15 Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) Md. Tanzim Anwar -

Higher Education in Public Universities in Bangladesh

4 Journal of Management and Science,. ISSN 2250-1819 / EISSN 2249-1260 – http://jms.nonolympictimes.org Higher Education in Public Universities in Bangladesh Md. Mortuza Ahmmed Lecturer, Department of Statistics, International University of Business, Agriculture and Technology (IUBAT), Dhaka-1230, Bangladesh DOI:10.26524/jms.2013.2 ABSTRACT: The key aims of higher education are to generate the new knowledge, explore research works on different social and development issues, anticipate the needs of the economy and prepare highly skilled workers. Throughout the World, universities change the society and remain the center of change and development. In Bangladesh a number of universities both public and private were set up so far theoretically emphasized on unlocking potential at all levels of society and creating a pool of highly trained individuals to contribute to the national development. But in practice these universities are very weak and do not change anything. Better understanding among teachers and students, introduction of modern teaching methods and dedication of teachers and students can improve the culture of higher education in Bangladesh. A proper academic calendar can bring discipline. To make the universities free from the clutches of politics can also improve the situation. Keywords: Higher Education; Bangladesh. 1. INTRODUCTION In Bangladesh there was a time when higher education used to be considered a luxury in a society of mass illiteracy. However, towards the turn of the last century the need for highly skilled manpower started to be acutely felt every sphere of the society for self-sustained development and poverty alleviation. Highly trained manpower not only contributes towards human resource development of a society through supplying teachers, instructors, researchers and scholars in the feeder institutions like schools, colleges, technical institutes and universities. -

Oral Hygiene Awareness and Practices Among a Sample of Primary School Children in Rural Bangladesh

dentistry journal Article Oral Hygiene Awareness and Practices among a Sample of Primary School Children in Rural Bangladesh Md. Al-Amin Bhuiyan 1,*, Humayra Binte Anwar 2, Rezwana Binte Anwar 3, Mir Nowazesh Ali 3 and Priyanka Agrawal 4 1 Centre for Injury Prevention and Research, Bangladesh (CIPRB), House B162, Road 23, New DOHS, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1206, Bangladesh 2 BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, 68 Shahid Tajuddin Ahmed Sharani, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh; [email protected] 3 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) Shahbag, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh; [email protected] (R.B.A.); [email protected] (M.N.A.) 4 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +880-2-58814988; Fax: +880-2-58814964 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 14 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: Inadequate oral health knowledge and awareness is more likely to cause oral diseases among all age groups, including children. Reports about the oral health awareness and oral hygiene practices of children in Bangladesh are insufficient. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the oral health awareness and practices of junior school children in Mathbaria upazila of Pirojpur District, Bangladesh. The study covered 150 children aged 5 to 12 years of age from three primary schools. The study reveals that the students have limited awareness about oral health and poor knowledge of oral hygiene habits. Oral health awareness and hygiene practices amongst the school going children was found to be very poor and create a much-needed niche for implementing school-based oral health awareness and education projects/programs. -

Mobasser Monem, Ph

Professor Sk. Tawfique M. Haque, Ph.D. OFFICIAL ADDRESS HOME ADDRESS South Asian Institute of Policy and Governance (SIPG) House #32, Road #4, Apt# C2 and Department of Political Science and Sociology Dhanmondi R/A, Dhaka North South University Bangladesh Plot-15, Block-B, Bashundhara Baridhara, Room # 1075, NAC, Dhaka- 1229 Phone: + 88 02 55668200 extn: 2162 (Work), + 88 01711 520266 (Cell), +8852016 (Fax), E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] SUMMARY OF KEY EXPERIENCES AND COMPETENCIES University teaching with more than 12 years of undergraduate and postgraduate lecturing experience in Bangladesh, Norway and Nepal in the field of Social Sciences. Editorial/journal management Publications including refereed journals articles, book and book-chapters Ph.D., and Master thesis supervision of students at North South University, BRAC University, National Defense College of Bangladesh and Tribhuvan University, Nepal. Long experience of project development and management work with such organizations as UNDP, World Bank, DFID, JICA, CIDA, NORAD and various government and non-government agencies in Bangladesh in the fields of urban/local governance, institutional development and capacity building, monitoring and evaluation of development programs, primary and higher education and civil service capacity building and reform Extensive fieldwork/commissioned research activities including participatory/rapid appraisals/learning Local governance and institutional capacity building Team building, communication and interpersonal -

Debapriya Bhattacharya

Debapriya Bhattacharya Distinguished Fellow E-mail: [email protected] Skype: debapriyacpd Executive Assistant Tel: (8802) 9134438 (Direct) PABX: (8802) 9141703, 9143326; Ext: 144 Cell: (88) 01720421881 Fax: (8802) 813 0951 Dr Debapriya Bhattacharya, a macro-economist and public policy analyst, is a Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) – a globally reputed think-tank in Bangladesh. He is the Chair of Southern Voice on Post-MDG International Development Goals - a network of 48 think tanks from South Asia, Africa, and Latin America that has identified a unique space and scope for itself to contribute to this post-MDG dialogue. He also chairs LDC IV Monitor – a partnership of development organisation which seeks to provide an independent assessment of the implementation of the Istanbul Programme of Action (IPoA) adapted at the Fourth United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries (LDCs). He was the Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Bangladesh to the WTO, UN office, and other international organisations in Geneva and Vienna (2007-2009). He was concurrently accredited to the Holy See in Vatican. As Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Bangladesh in Geneva, led delegation to various forums of Doha Round including the July Ministerial 2008. Was member of the “Green Room” of the DG, WTO. Participated actively in many high level international conferences; was the Deputy Team Leader to UNCTAD XII and HLM on Aid Effectiveness in Accra (2008). He was the President of UNCTAD’s governing board as well as the coordinator of LDC Group in the UN System in Geneva. Later he had been the Special Adviser on LDCs to the Secretary General, UNCTAD (2009-2010). -

Chapter-3 Monitoring the Behaviour of Law Enforcement Agencies

Odhikar Report 2006 Published by Odhikar House No. 65 (2nd Floor), Block-E Road No. 17/A, Banani Dhaka-1213, Bangladesh Tel: 880 2 9888587, Fax: 880 2 9886208 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.odhikar.org Supported by Academy for Educational Development (AED) Eureka House No. 10 A Road No. 25 A, Banani Dhaka-1213, Bangladesh Tel: 880 2 9894016 Fax: 880 2 9894016 (Ext. 106) Website: www.aed-bd.org Cover Design Md. Sazzad Hussain Copyright c Odhikar Any material published in this report may be reproduced with acknowledgement to Odhikar Table of content Chapter 1 : AED and Odhikar: Four Years of Partnership 7 Chapter 2 : Civil and Political Rights in Bangladesh 11 Chapter 3 : Monitoring the Behaviour of 21 Law Enforcement Agencies Chapter 4 : Documentation and Fact Finding on 35 Human Rights Violations Chapter 5 : Human Rights Advocacy: The Media Roundtables 39 and a Regional Discussion Meeting Chapter 6 : Successful Outcomes of the Project 49 ANNEXTURE Annex-i Fact finding reports 2006 53 Annex-ii Keynote paper for Roundtable Meeting on 171 ‘Police Behaviour in Crowd Management’ Annex-iii Papers presented at the Regional Discussion Meeting 181 on Security and Law: South Asian perspective Annex-iv Newspaper clippings 215 Acknowledgement The Academy for Educational Development had supported Odhikar's work for four years - the last year being an extension to help the organisation complete its activities, carry out follow-up missions of noteworthy incidents of human rights violations and improve its fact finding skills. Odhikar would like to thank the AED for extending its project for another year, where time could also be spent in evaluating the work of the previous years. -

Media Monitoring (Clipping)

Media Monitoring (Clipping) Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: B3, Col: 1-4 Publication: The Daily Star Colour/B&W: B&W Language: English Size: 4 Col X 4 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 8, Col: 3-5 Publication: Financial Express Colour/B&W: B&W Language: English Size: 3 Col X 6.5 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 2, Col: 2-4 Publication: New Age Colour/B&W: B&W Language: English Size: 3 Col X 4 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 16, Col: 1-4 Publication: News Today Colour/B&W: B&W Language: English Size: 4 Col X 4 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 15, Col: 5-7 Publication: Prothom Alo Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 3 Col X 5 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 3, Col: 4-5 Publication: Jugantor Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 2 Col X 6 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 11, Col: 4-5 Publication: Ittefaq Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 2 Col X 7.5 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 19, Col: 4 Publication: Shamokal Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 1 Col X 4 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 1, Col: 5 Publication: Jaijaidin Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 1 Col X 14 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 1, Col: 6-7 Publication: Amar Desh Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 2 Col X 11 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 8, Col: 1 Publication: Amader Shomoy Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 1 Col X 12 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 6, Col: 2-4 Publication: Bhorer Kagoj Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 3 Col X 4.5 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: Client: LIRNEasia Position: Page: 1, Col: 6-8 Publication: Banglabazar Patrika Colour/B&W: B&W Language: Bangla Size: 3 Col X 5.5 Inches Date: 29-06-2009 Comments: . -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age. -

Expanding Access to Education in Bangladesh1

Expanding Access to Education in Bangladesh1 Naomi Hossain Widespread poverty and biases against women and girls make Bangladesh an unlikely setting for groundbreaking achievements in education for girls and the poor. Yet Bangladesh has succeeded in dramatically expanding access to basic education in the last two decades, particularly among girls. Today there are 18 million primary school places - in theory enough for the entire school-aged population.2 Gross enrolment ratios in primary schools have exceeded 100 per cent,3 and the once-stark gender disparity has been completely eliminated. Girls now constitute 55 per cent of Bangladesh’s total primary school enrolment, up from a third in 1990. In just two decades, the number of girls enrolled in secondary school has increased by more than 600 per cent, from 600,000 in 1980 to 4 million in 2000. It is now one of the largest oprimary It is not all good news in Bangladesh’s primary education sector: low quality education presents a serious obstacle to children’s learning achievements, although interventions are now in place to tackle some of the most acute constraints. There are also growing concerns about those left behind - the children of the urban slums and ethnic minority communities whom providers still find ‘hard-to-reach’. Given the success with which the gender disadvantage of poor girls has been addressed, it is striking that the single largest disadvantaged group now seems to be boys from the poorest households: they are more likely to be in paid work from an early age than to be in school.