Lycaena Hermes)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5635/docket-no-fws-hq-es-2019-0009-ff09e21000-fxes11190900000-167-75635.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/10/2019 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-21478, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–ES–2019–0009; FF09E21000 FXES11190900000 167] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Domestic and Foreign Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notification of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of review. SUMMARY: In this candidate notice of review (CNOR), we, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), present an updated list of plant and animal species that we regard as candidates for or have proposed for addition to the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. Identification of candidate species can assist environmental planning efforts by providing advance notice of potential listings, and by allowing landowners and resource managers to alleviate threats and thereby possibly remove the need to list species as endangered or threatened. Even if we subsequently list a candidate species, the early notice provided here could result in more options for species management and recovery by prompting earlier candidate conservation measures to alleviate threats to the species. This document also includes our findings on resubmitted petitions and describes our 1 progress in revising the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants (Lists) during the period October 1, 2016, through September 30, 2018. -

Guidelines for Determining Significance and Report Format and Content Requirements

COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO GUIDELINES FOR DETERMINING SIGNIFICANCE AND REPORT FORMAT AND CONTENT REQUIREMENTS BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES LAND USE AND ENVIRONMENT GROUP Department of Planning and Land Use Department of Public Works Fourth Revision September 15, 2010 APPROVAL I hereby certify that these Guidelines for Determining Significance for Biological Resources, Report Format and Content Requirements for Biological Resources, and Report Format and Content Requirements for Resource Management Plans are a part of the County of San Diego, Land Use and Environment Group's Guidelines for Determining Significance and Technical Report Format and Content Requirements and were considered by the Director of Planning and Land Use, in coordination with the Director of Public Works on September 15, 2O1O. ERIC GIBSON Director of Planning and Land Use SNYDER I hereby certify that these Guidelines for Determining Significance for Biological Resources, Report Format and Content Requirements for Biological Resources, and Report Format and Content Requirements for Resource Management Plans are a part of the County of San Diego, Land Use and Environment Group's Guidelines for Determining Significance and Technical Report Format and Content Requirements and have hereby been approved by the Deputy Chief Administrative Officer (DCAO) of the Land Use and Environment Group on the fifteenth day of September, 2010. The Director of Planning and Land Use is authorized to approve revisions to these Guidelines for Determining Significance for Biological Resources and Report Format and Content Requirements for Biological Resources and Resource Management Plans except any revisions to the Guidelines for Determining Significance presented in Section 4.0 must be approved by the Deputy CAO. -

Rin 1018–Bc57

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 01/08/2020 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2019-28461, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [Docket No. FWS–R8–ES–2017–0053; 4500030113] RIN 1018–BC57 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Species Status for the Hermes Copper Butterfly with 4(d) Rule and Designation of Critical Habitat AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), propose to list the Hermes copper butterfly (Lycaena [Hermelycaena] hermes), a butterfly species from San Diego County, California, and Baja California, Mexico, as a threatened species and propose to designate critical habitat for the species under the Endangered Species Act (Act). If we finalize this rule as proposed, it would extend the Act’s protections to this species as described in the proposed rule provisions issued under section 4(d) of the Act, and designate approximately 14,249 hectares (35,211 acres) of critical habitat in San Diego County, California. We also announce the availability of a draft economic analysis (DEA) of the proposed designation of critical habitat for the Hermes copper butterfly. DATES: We will accept comments received or postmarked on or before [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. Comments submitted electronically using the Federal eRulemaking Portal (see ADDRESSES below) must be received by 11:59 p.m. Eastern Time on the closing date. We must receive requests for public hearings, in writing, at the address shown in FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT by [INSERT DATE 45 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. -

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 72/Thursday, April 14, 2011/Proposed Rules

20918 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 72 / Thursday, April 14, 2011 / Proposed Rules not provide information indicating how require empirical proof of a threat. The DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR climate change might potentially impact combination of exposure and some the prairie chub. The prairie chub has corroborating evidence of how the Fish and Wildlife Service persisted for millennia with periods of species is likely impacted could suffice. extreme weather events, such as The mere identification of factors that 50 CFR Part 17 droughts and floods. If climate change could impact a species negatively may [Docket No. FWS–R8–ES–2010–0031; MO causes more extreme weather events, not be sufficient to compel a finding 92210–0–0008–B2] there is no information to indicate that that listing may be warranted. The such events will have a negative impact information must contain evidence Endangered and Threatened Wildlife on the prairie chub. At this time, we sufficient to suggest that these factors and Plants; 12-Month Finding on a lack sufficient certainty to know may be operative threats that act on the Petition To List Hermes Copper specifically how climate change will species to the point that the species may Butterfly as Endangered or Threatened affect the species. We are not aware of meet the definition of threatened or any data at an appropriate scale to endangered under the Act. AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, evaluate habitat or population trends for Interior. Because we have found that the the prairie chub within its range, make ACTION: Notice of 12-month petition petition presents substantial predictions about future trends, or finding. -

Monitoring the Status of Hermes Copper (Lycaena Hermes) on Conserved Lands in San Diego County: 2010 - 2012

Monitoring the Status of Hermes Copper (Lycaena hermes) on Conserved Lands in San Diego County: 2010 - 2012 Photo: Spring L. Strahm Prepared For: San Diego Association of Governments Keith Greer MOU # 5001442 Prepared By: SL Strahm1, DA Marschalek1,2, DH Deutschman1 and ME Berres2 1 San Diego State University 2 University of Wisconsin San Diego, CA 92182 Madison, WI 53706 Date: December 31, 2012 Executive Summary The Hermes copper butterfly, Lycaena [Hermelycaena] hermes, is a rare butterfly endemic to San Diego County, which is threatened by recent urbanization and wildfires. In 2011 the United States Fish and Wildlife Service placed Hermes copper on its candidate species list. This SANDAG funded project began in 2010, focusing on collecting population data for the first two years. In 2012 the emphasis shifted to resolving critical biological uncertainties which will deepen our understanding of the species for improved planning and management of Hermes copper. This report is structured around a conceptual model developed collaboratively during a workshop on conceptual models for monitoring and management. We addressed a number of model aspects, including population sizes and locations, dispersal and genetics, egg biology and reproductive behavior. In 2012 the number of Hermes copper adults observed was moderate when compared to totals of 2010 and 2011, however we had few detections at sparsely populated sites in the northern portion of its distribution. We also added two additional sites at Boulder Creek Road (near Cuyamaca Peak) and Potrero Peak (near Potrero). Boulder Creek Road was densely populated, Potrero Peak was moderate. Landscape genetics suggest that individuals from peripheral populations in the northern and western portion of the Hermes copper distribution generally exhibit increased differentiation compared to populations in the central region of their range (McGinty Mountain, Sycuan Peak, and Lawson Peak areas). -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Monday, November 9, 2009 Part III Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Native Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notice of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions; Proposed Rule VerDate Nov<24>2008 17:08 Nov 06, 2009 Jkt 220001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\09NOP3.SGM 09NOP3 jlentini on DSKJ8SOYB1PROD with PROPOSALS3 57804 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 215 / Monday, November 9, 2009 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR October 1, 2008, through September 30, for public inspection by appointment, 2009. during normal business hours, at the Fish and Wildlife Service We request additional status appropriate Regional Office listed below information that may be available for in under Request for Information in 50 CFR Part 17 the 249 candidate species identified in SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. General [Docket No. FWS-R9-ES-2009-0075; MO- this CNOR. information we receive will be available 9221050083–B2] DATES: We will accept information on at the Branch of Candidate this Candidate Notice of Review at any Conservation, Arlington, VA (see Endangered and Threatened Wildlife time. address above). and Plants; Review of Native Species ADDRESSES: This notice is available on Candidate Notice of Review That Are Candidates for Listing as the Internet at http:// Endangered or Threatened; Annual www.regulations.gov, and http:// Background Notice of Findings on Resubmitted endangered.fws.gov/candidates/ The Endangered Species Act of 1973, Petitions; Annual Description of index.html. -

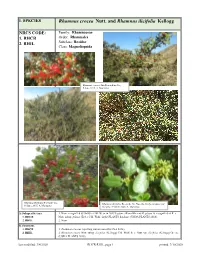

Rhamnus Crocea Nutt

I.SPECIES Rhamnus crocea Nutt. and Rhamnus ilicifolia Kellogg NRCS CODE: Family: Rhamnaceae 1. RHCR Order: Rhamnales 2. RHIL Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Rhamnus crocea, San Bernardino Co., 5 June 2015, A. Montalvo Rhamnus ilicifolia, Riverside Co., Rhamnus ilicifolia, Riverside Co. Note the finely serrulate leaf 10 June 2015. A. Montalvo margins. 7 March 2008. A. Montalvo A. Subspecific taxa 1. None recognized by Sawyer (2012b) or in 2019 Jepson e-Flora whereas R. pilosa is recognized as R. c. 1. RHCR Nutt. subsp. pilosa (Trel.) C.B. Wolf in the PLANTS database (USDA PLANTS 2018). 2. RHIL 2. None B. Synonyms 1. RHCR 1 . Rhamnus croceus (spelling variant noted by FNA 2018) 2. RHIL 2. Rhamnus crocea Nutt. subsp. ilicifolia (Kellogg) C.B. Wolf; R. c. Nutt. var. ilicifolia (Kellogg) Greene (USDA PLANTS 2018) last modified: 3/4/2020 RHCR RHIL, page 1 printed: 3/10/2020 C. Common name The name red-berry, redberry, redberry buckthorn, California red-berry, evergreen buckthorn, spiny buckthorn, and hollyleaf buckthorn have been used for multiple taxa of Rhamnus (Painter 2016 a,b) 1. RHCR 1. Spiny redberry (Sawyer 2012a); also little-leaved redberry (Painter 2016a) 2. RHIL 2. Hollyleaf redberry (Sawyer 2012b); also holly-leaf buckthorn, holly-leaf coffeeberry (Painter 2016b) D. Taxonomic relationships There are about 150 species of Rhamnus worldwide and 14 in North America, 6 of which were introduced from other continents (Nesom & Sawyer 2018, FNA). This is after splitting the genus into Rhamnus (buckthorns and redberries) and Frangula (coffeeberries) based on a combination of fruit, leaf venation, and flower traits (Johnston 1975, FNA). -

Rhamnus Crocea Nutt. and Rhamnus Ilicifolia Kellogg

I.SPECIES Rhamnus crocea Nutt. and Rhamnus ilicifolia Kellogg NRCS CODE: Family: Rhamnaceae 1. RHCR Order: Rhamnales 2. RHIL Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Rhamnus crocea, San Bernardino Co., 5 June 2015, A. Montalvo Rhamnus ilicifolia, Riverside Co., Rhamnus ilicifolia, Riverside Co. Note the finely serrulate leaf 10 June 2015. A. Montalvo margins. 7 March 2008. A. Montalvo A. Subspecific taxa 1. None recognized by Sawyer (2012b) or in 2019 Jepson e-Flora whereas R. pilosa is recognized as R. c. 1. RHCR Nutt. subsp. pilosa (Trel.) C.B. Wolf in the PLANTS database (USDA PLANTS 2018). 2. RHIL 2. None B. Synonyms 1. RHCR 1 . Rhamnus croceus (spelling variant noted by FNA 2018) 2. RHIL 2. Rhamnus crocea Nutt. subsp. ilicifolia (Kellogg) C.B. Wolf; R. c. Nutt. var. ilicifolia (Kellogg) Greene (USDA PLANTS 2018) last modified: 3/4/2020 RHCR RHIL, page 1 printed: 3/10/2020 C. Common name The name red-berry, redberry, redberry buckthorn, California red-berry, evergreen buckthorn, spiny buckthorn, and hollyleaf buckthorn have been used for multiple taxa of Rhamnus (Painter 2016 a,b) 1. RHCR 1. Spiny redberry (Sawyer 2012a); also little-leaved redberry (Painter 2016a) 2. RHIL 2. Hollyleaf redberry (Sawyer 2012b); also holly-leaf buckthorn, holly-leaf coffeeberry (Painter 2016b) D. Taxonomic relationships There are about 150 species of Rhamnus worldwide and 14 in North America, 6 of which were introduced from other continents (Nesom & Sawyer 2018, FNA). This is after splitting the genus into Rhamnus (buckthorns and redberries) and Frangula (coffeeberries) based on a combination of fruit, leaf venation, and flower traits (Johnston 1975, FNA). -

Butterfly!Survey!

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Vermont!Butterfly!Survey! ! 2002!–!2007! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Final!Report!to!the!Natural!Heritage!Information! ! Project!of!the!Vermont!Department!of!Fish!and! Wildlife! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! September!30,!2010! ! Kent!McFarland,!Project!Director! ! Sara!Zahendra,!Staff!Biologist! Vermont!Center!for!Ecostudies! ! Norwich,!Vermont!05055! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! Acknowledgements!............................................................................................................................!4! Introduction!and!Methodology!..........................................................................................................!6! Project!Planning!and!Management!...............................................................................................................!6! Recording!Methods!and!Data!Collection!.......................................................................................................!7! Data!Processing!............................................................................................................................................!9! PreKProject!Records!....................................................................................................................................!11! Summary!of!Results!.........................................................................................................................!11! Conservation!of!Vermont!Butterflies!................................................................................................!19! -

![Species Status Assessment for the Hermes Copper Butterfly (Lycaena [Hermelycaena] Hermes) Version 1.0](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2084/species-status-assessment-for-the-hermes-copper-butterfly-lycaena-hermelycaena-hermes-version-1-0-3342084.webp)

Species Status Assessment for the Hermes Copper Butterfly (Lycaena [Hermelycaena] Hermes) Version 1.0

Species Status Assessment for the Hermes copper butterfly (Lycaena [Hermelycaena] hermes) Version 1.0 Hermes copper butterfly. Photo credit Mike Couffer (used with permission). Month 2017 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 8 Carlsbad, CA 1 Chapter 1. Introduction, Data, and Analytical Framework Introduction The Hermes copper butterfly is a medium-sized butterfly currently found in San Diego County, California, and Baja California, Mexico. The Hermes copper butterfly has been a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act), since the 12-month finding published in 2011 (Service 2011). The Species Status Assessment (SSA) is intended to be an in- depth review of the species’ biology and threats, an evaluation of its biological status, and an assessment of the resources and conditions needed to maintain long-term viability. Comment [MD1]: I would mention the IUCN threat status of the species (Vulnerable) in the introduction to underpin the importance of the conservation of this endemic species Methods and Background (http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/12435/0). This document draws scientific information from resources such as primary peer-reviewed literature, reports submitted to the Service and other public agencies, species occurrence information in GIS databases, and expert experience and observations. It is preceded by, and draws upon analyses presented in, other Service documents, including the 12-month finding (Service 2011) and the Species Assessment and Listing Priority Assignment Form associated with the most recent Candidate Notice of Review (Service 2015). Finally, we coordinate closely with our partners engaged in ongoing research and conservation efforts. This assures consideration of the most current scientific and conservation status information. -

How Politics Drowned out Science for Ten Endangered Species This Report Is a Distress Signal States, and Others Have Resisted for At-Risk Plants and Animals

How Politics Drowned Out Science for Ten Endangered Species This report is a distress signal states, and others have resisted for at-risk plants and animals. federal management and adapting Introduction We can only successfully recover to climate change. States have If you were a 1970s biologist who studied declining ocelots or Hermes butterflies, you might them−under the Endangered Species tried to manage at-risk wildlife take action. You might write a bill. And if you wrote that bill, it might have looked very simi- Act−when we follow science. Yet, themselves, and then they kept us lar to the Endangered Species Act. And because it follows the science, it’s our nation’s most we’ve fallen down on the job in in the dark on their conservation effective law in preventing threatened and endangered species from going extinct. many ways. Special interests, state actions and population numbers. agencies, and even some members Thanks to the Act, when a biologist decides whether to list a species as endangered, the only of Congress have always applied As a result, species across the thing that the biologist can consider is science. Other matters, including economics, come pressure on species decisions. The country, on land and in our into play later. The science, however, stays central to every step. difference now is that the Trump waters, have suffered. This report Administration is itself infiltrated examines the lack of scientific But will that approach stand under the Trump Administration? Will U.S. Fish and Wildlife with special interest officials who decisions for: dunes sagebrush Executive Summary Service (FWS) biologists be allowed to follow the science? There are many reasons to fear completely disregard science. -

Candidate Notice of Review

Wednesday, November 10, 2010 Part III Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Native Species That Are Candidates for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notice of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions; Proposed Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 17:02 Nov 09, 2010 Jkt 223001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\10NOP3.SGM 10NOP3 jlentini on DSKJ8SOYB1PROD with PROPOSALS3 69222 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 217 / Wednesday, November 10, 2010 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Wildlife and Plants during the period Species-specific information and October 1, 2009, through September 30, materials we receive will be available Fish and Wildlife Service 2010. for public inspection by appointment, We request additional status during normal business hours, at the 50 CFR Part 17 information that may be available for appropriate Regional Office listed below [Docket No. FWS–R9–ES–2010–0065; MO– the 251 candidate species identified in under Request for Information in 9221050083–B2] this CNOR. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. General DATES: We will accept information on information we receive will be available Endangered and Threatened Wildlife any of the species in this Candidate at the Branch of Candidate and Plants; Review of Native Species Notice of Review at any time. Conservation, Arlington, VA (see That Are Candidates for Listing as address above). Endangered or Threatened; Annual ADDRESSES: This notice is available on Candidate Notice of Review Notice of Findings on Resubmitted the Internet at http:// Petitions; Annual Description of www.regulations.gov and http:// Background Progress on Listing Actions www.fws.gov/endangered/what-we-do/ cnor.html.