Voting Issues: a Brief History of Preference Aggregation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Behavior in Exhaustive Ballot Voting: What Can We Learn from the Fifa World Cup 2018 and 2022 Host Elections?

Daniel Karabekyan STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT VOTING: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE FIFA WORLD CUP 2018 AND 2022 HOST ELECTIONS? BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: ECONOMICS WP BRP 130/EC/2016 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE SERIES: ECONOMICS Daniel Karabekyan2 STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT VOTING: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE FIFA WORLD CUP 2018 AND 2022 HOST ELECTIONS?*3 There are many allegations about whether FIFA world cup host countries were chosen honestly or not. We analyse the results of the FIFA Executive Committee voting and reconstruct the set of possible voting situations compatible with the results of each stage. In both elections, we identify strategic behaviour and then analyse the results for honest voting under all compatible voting situations. For the 2018 FIFA world cup election Russia is chosen for all profiles. For the 2022 elections the result depends on the preferences of the FIFA president Sepp Blatter who served as a tie-breaker. If Sepp Blatter prefers Qatar over South Korea and Japan, then Qatar would have been chosen for all profiles. Otherwise there are the possibility that South Korea or Japan would have been chosen as the 2022 host country. Another fact is that if we consider possible vote buying, then it is shown, that the bribery of at least 2 committee members would have been required to guarantee winning of Russia bid and at least 1 member for Qatar. -

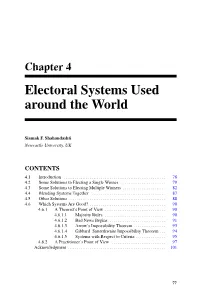

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

Exhaustive Ballot By-Law

Exhaustive Ballot By-law AUSTRALIAN WEIGHTLIFTING FEDERATION LIMITED BY-LAW 4 EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT This By-law is made by the Australian Weightlifting Federation (AWF) Board under Clause 20 of the AWF Constitution. It is binding on AWF and all members of AWF. Approved by the AWF Board on 12th June, 2014 12 June 2014 Page 1 Exhaustive Ballot By-law 1. EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT BY-LAW This By-law sets out the procedure for voting at elections of Elected Directors. This By- law is made by Australian Weightlifting Federation (AWF) pursuant to clause 7.2.1.3 of the Australian Weightlifting Federation Constitution. 2. DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION In this By-law, unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms and expressions shall have the following meanings: Board means the Board of AWF as constituted from time to time. Elected Director means a Director elected to the Board of the AWF in accordance with clause 13 of the AWF Constitution. Member means a member for the time being under clause 5 of the AWF Constitution. All other defined terms and expressions shall have the same meaning as in the AWF Constitution. In the event of any conflict, the definition in the AWF Constitution shall prevail. 2. ELECTION BY EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT 2.1 In accordance with clause 13.2.2.4 of the AWF Constitution, voting at elections of Elected Directors shall be conducted by exhaustive ballot. 2.2. Members shall be advised of nominees for election prior to the commencement of each round of the election process. 3. NOMINATION EQUALS VACANCIES OR NUMBER OF NOMINATIONS LESS THAN VACANCIES 3.1 If the number of nominations received for the Board is equal to the number of vacancies to be filled or if there are insufficient nominations received to fill all vacancies on the Board, then those nominated shall only be elected if they are elected by the Members by secret ballot (Clause 13.7.3 of the AWF Constitution). -

Sequential Elimination Vs. Instantaneous Voting∗

Sequential Elimination vs. Instantaneous Voting∗ Parimal Kanti Bag† Hamid Sabourian‡ Eyal Winter§ April 22, 2007 Abstract A class of sequential elimination voting eliminating candidates one-at-a- time based on repeated ballots is superior to well-known single-round and semi-sequential elimination voting rules: if voters are strategic the former will induce the Condorcet winner in unique equilibrium, whereas the latter may fail to select it. In addition, when there is no Condorcet winner the outcome of sequential elimination voting always belongs to the ‘top cycle’. The proposed sequential family includes an appropriate adaptation of almost all standard single-round voting procedures. The importance of one-by-one elimination and repeated ballots for Condorcet consistency are further em- phasized by its failure for voting rules such as plurality runoff rule, exhaus- tive ballot method, and a variant of instant runoff voting. JEL Classification Numbers: P16, D71, C72. Key Words: Sequential elimination voting, Con- dorcet winner, top cycle, weakest link voting, scoring rule, exhaustive ballot, instant runoff voting, Markov equilibrium, complexity aversion. ∗At various stages this work has been presented at the 2003 Econometric Society European Meetings, 2005 Wallis Political Economy Conference, 2005 Conference at the Indian Statistical Institute, 2006 Econometric Society Far Eastern Meetings, and seminars at Birmingham, Keele, LSE, NUS (Singapore), Oxford and York universities. We thank the conference and seminar participants for important feedbacks. For errors or omissions, we remain responsible. †Department of Economics, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH, U.K.; E-mail: [email protected] ‡Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge, Sidgwick Avenue, Cambridge CB39 DD, U.K.; E-mail: [email protected] §Economics Department, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91905, Israel; E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction Any assessment of a voting rule is likely to be based on the extent it aggregates individual preferences. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Party Politics of Political Decentralization Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6jw6f00k Author Wainfan, Kathryn Tanya Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Party Politics of Political Decentralization A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Kathryn Tanya Wainfan 2018 c Copyright by Kathryn Tanya Wainfan 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Party Politics of Political Decentralization by Kathryn Tanya Wainfan Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Michael F. Thies, Chair In this dissertation, I ask why certain types of parties would agree to support creating or empowering sub-national governments. In particular, I focus on nationalized parties { those that gain support from throughout a country. Political decentralization can negatively impact nationalized parties in at least two ways. First, it reduces the amount of power a party can enjoy should it win control of the national-level government. Second, previous studies show that political decentralization can increase party denationalization, meaning regional parties gain more support, even during national-level elections. I argue that nationalized parties may support decentralization when doing so reduces the ideological conflicts over national-level policy among voters whose support they seek. By altering political institutions, a party may be able to accommodate differing policy prefer- ences in different parts of the country, or limit the damage to the party's electoral fortunes such differences could create. -

Voting Systems - the Alternatives

Voting Systems - The Alternatives Research Paper 97/26 13 February 1997 This Research Paper looks at the background to the current debate on electoral reform, and other alternative voting systems. It summarises the main arguments for and against change to the current First Past the Post (FPTP) system, and examines the main alternatives. The Paper also provides a glossary of terms. It replaces Library Background Paper No 299, Voting Systems, 7.9.1992. Oonagh Gay Home Affairs Section House of Commons Library Summary There has been a long debate in the United Kingdom about the merits or otherwise of the current First Past the Post system (FPTP). Nineteenth century reformers favoured the Single Transferable Vote, and in 1917/18 and 1930/31 Bills incorporating the Alternative Vote passed the Commons. There was a revival of interest in electoral reform in the 1970s and 1980s and the Labour Party policy is to hold a referendum on voting systems, if elected.1 The arguments for and against reform can be grouped into a number of categories; fairness, the constituency link, 'outcome' arguments, representation of women and ethnic minorities. The different systems used in other parts of the world are discussed, in particular, the Alternative Vote, Second Ballot, Supplementary Vote, Additional Member System, List systems and Single Transferable Vote, but with the arguments for and against each system summarised. 1 on which see Research Paper no 97/10 Referendum: recent proposals, 24.1.97 Contents page I Introduction 5 A. History 7 B. The current debate 9 II Arguments 14 Introduction and Summary 14 III Voting methods 31 1. -

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy an Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu Scholars of political institutions debate the level by which different institutions help or impair the realization of various democratic principles. 1 There are stormy debates, for example, over which electoral systems and government systems better serve the principles of democracy. 2 But in the case of candidate selection methods there is no such discourse, probably due to the relative underdevelopment of this field of research (Hazan and Rahat, 2006a). Nevertheless, candidate selection methods are important for democracy in the same sense that electoral systems are. Both institutions are links in the chain of the electoral connection that stands at the center of modern representative democracy (Narud et al., 2002). In order to be elected to parliament, one should first (in almost all cases) be selected as a candidate of a specific party. Candidate selection is the “process by which a political party decides which of the persons legally eligible to hold an elective office will be designated on the ballot and in election communications as its recommended and supported candidate or list of candidates” (Ranney, 1981: 75). Candidate selection takes place almost entirely within particular parties. There are very few countries where the legal system specifies criteria for candidate selection and even fewer in which the legal system suggests more than central guidelines (Muller and Sieberer, 2006: 441; Rahat, 2007). The aim of this article is quite ambitious – to open the debate on the question, “Which candidate selection method is more democratic?” It does this by suggesting guidelines for identifying the ramifications of central elements of candidate selection methods for various democratic dimensions – participation, competition, representation and responsiveness – and by analyzing their possible role in supplying checks and balances. -

Multi-Stage Voting, Sequential Elimination and Condorcet Consistency∗

Multi-Stage Voting, Sequential Elimination and Condorcet Consistency∗ Parimal Kanti Bag Hamid Sabourian Department of Economics Faculty of Economics National University of Singapore University of Cambridge AS2 Level 6, 1 Arts Link Sidgwick Avenue, Cambridge CB39 DD Singapore 117570 United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] and Eyal Winter Economics Department The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Jerusalem 91905, Israel E-mail: [email protected] Address for correspondence: Hamid Sabourian, Faculty of Economics, Univer- sity of Cambridge, Sidgwick Avenue, Cambridge CB39 DD, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected]; Tel: 44-1223-335223; Fax: 44-1223- 335475 Running head: Sequential elimination and Condorcet consistency ∗We thank two anonymous referees of this journal and the editor, Alessandro Lizzeri, for very detailed comments and helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. At various stages the work has been presented at the 2003 Econometric Society European Meetings, 2005 Wallis Political Economy Conference, 2005 Models and Methods Conference at the Indian Statistical Institute, 2006 Econometric Society Far Eastern Meetings, 2007 SAET Conference (Kos), 2008 Workshop on Game Theory (Milan), and seminars at Birmingham, Cambridge, Essex, Keele, LSE, NUS (Singapore), Oxford and York universities. We thank the conference and seminar participants. For errors or omissions, we remain responsible. 1 Abstract A class of voting procedures based on repeated ballots and elimination of one candidate in each round is shown to always induce an outcome in the top cycle and is thus Condorcet consistent, when voters behave strategically. This is an important class as it covers multi-stage, sequential elimination ex- tensions of all standard one-shot voting rules (with the exception of negative voting), the same one-shot rules that would fail Condorcet consistency. -

The Mixed Member Proportional Representation System and Minority Representation

The Mixed Member Proportional Representation System and Minority Representation: A Case Study of Women and Māori in New Zealand (1996-2011) by Tracy-Ann Johnson-Myers MSc. Government (University of the West Indies) 2008 B.A. History and Political Science (University of the West Indies) 2006 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies In the Graduate Academic Unit of the School of Graduate Studies Supervisor: Joanna Everitt, PhD, Dept. of History and Politics Examining Board: Emery Hyslop-Margison, PhD, Faculty of Education, Chair Paul Howe, PhD, Dept. of Political Science Lee Chalmers, PhD, Dept. of Sociology External Examiner: Karen Bird, PhD, Dept. of Political Science McMaster University This dissertation is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK April, 2013 © Tracy-Ann Johnson-Myers, 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the relationship between women and Māori descriptive and substantive representation in New Zealand’s House of Representatives as a result of the Mixed Member Proportional electoral system. The Mixed Member Proportional electoral system was adopted in New Zealand in 1996 to change the homogenous nature of the New Zealand legislative assembly. As a proportional representation system, MMP ensures that voters’ preferences are proportionally reflected in the party composition of Parliament. Since 1996, women and Māori (and other minority and underrepresented groups) have been experiencing significant increases in their numbers in parliament. Despite these increases, there remains the question of whether or not representatives who ‘stand for’ these two groups due to shared characteristics will subsequently ‘act for’ them through their political behaviour and attitudes. -

A Program to Implement the Condorcet and Borda Rules in a Small-N Election

A program to implement the Condorcet and Borda rules in a small-n election Iain McLean and Neil Shephard Iain McLean ([email protected]) is Professor of Politics and Neil Shephard ([email protected]) is Professor of Economics, Oxford University. Address: Nuffield College, Oxford OX1 1NF, UK. Nuffield College Politics Working Paper 2004-W11 University of Oxford 1 A program to implement the Condorcet and Borda rules in a small-n election Introduction: The Condorcet and Borda criteria There are two defensible procedures for aggregating votes: the Condorcet rule and the Borda rule. Each may be used either to choose a winner or to rank the alternatives. To choose a winner, the Condorcet rule is: Select the option (if one exists) that beats each other option in exhaustive pairwise comparison And the Borda rule is: Select the option that on average stands highest in the voters’ rankings. To rank the alternatives, the Condorcet (also known as Copeland) rule is: Rank the options in descending order of their number of victories in exhaustive pairwise comparison. And the Borda rule is: Rank the options in descending order of their standing in the voters’ rankings. 2 These choice and ranking rules have properties, and defects, that are now well known. By Arrow’s (1951) General Possibility Theorem, neither ranking rule can satisfy the five Arrow conditions, because no ranking rule can. The Condorcet rule fails to satisfy universal domain, because a strong ordering does not always exist. For instance, there may be a top cycle, and no Condorcet winner. -

The Alternative Vote : in Theory and Practice

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2004 The Alternative Vote : In Theory and Practice Vanessa Beckingham Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Beckingham, V. (2004). The Alternative Vote : In Theory and Practice. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/ 952 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/952 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. THE ALTERNATIVE VOTE: IN THEORY AND PRACTICE BY VANESSA BECKINGHAM BA (ARTS) A thesis submitted in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Bachelor of Arts (Politics and Government) with Honours Faculty of Community Services, Education and Social Sciences Edith Cowan University Date of Submission: II March 2004 USE OF THESIS The Use of Thesis statement is not included in this version of the thesis. -

Approved 1 Australian Canoeing Inc By-Law 16

APPROVED 1 AUSTRALIAN CANOEING INC BY-LAW 16 EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT BY-LAW In accordance with Rule 34.1 of the Australian Canoeing Constitution, the following By-Law is adopted by the Australian Canoeing Board. This Exhaustive Ballot By-Law sets out the procedure for voting at elections of Interested Directors under Rule 26.2 of the Australian Canoeing Constitution. 1. In accordance with Rule 26.2(f) of the Australian Canoeing Constitution, voting at elections of Interested Directors shall be conducted by exhaustive ballot. 2. Members shall be advised of nominees for election prior to the commencement of each round of the election process. Nomination equals vacancies or number of nominations less than vacancies 3. If the number of nominations received for the Board is equal to the number of vacancies to be filled or if there are insufficient nominations received to fill all vacancies on the Board, then those nominated shall only be elected if they are elected by the Members by secret ballot (Rule 26.2(d) of the Australian Canoeing Constitution). Ballot papers shall be prepared for each nominee. The ballot paper shall include two boxes, being YES and NO. The members will be required to mark one box on the ballot paper, indicating whether they agree to the election of the nominee. The nominee will be elected if the majority of members mark the YES box. If the nominees are not elected or if there are vacancies to be filled, further nominations shall be called for at the Annual General Meeting from the floor and the procedure set out in this clause 3 shall be followed for each further nominee.