UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Father of the House Sarah Priddy

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06399, 17 December 2019 By Richard Kelly Father of the House Sarah Priddy Inside: 1. Seniority of Members 2. History www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06399, 17 December 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Seniority of Members 4 1.1 Determining seniority 4 Examples 4 1.2 Duties of the Father of the House 5 1.3 Baby of the House 5 2. History 6 2.1 Origin of the term 6 2.2 Early usage 6 2.3 Fathers of the House 7 2.4 Previous qualifications 7 2.5 Possible elections for Father of the House 8 Appendix: Fathers of the House, since 1901 9 3 Father of the House Summary The Father of the House is a title that is by tradition bestowed on the senior Member of the House, which is nowadays held to be the Member who has the longest unbroken service in the Commons. The Father of the House in the current (2019) Parliament is Sir Peter Bottomley, who was first elected to the House in a by-election in 1975. Under Standing Order No 1, as long as the Father of the House is not a Minister, he takes the Chair when the House elects a Speaker. He has no other formal duties. There is evidence of the title having been used in the 18th century. However, the origin of the term is not clear and it is likely that different qualifications were used in the past. The Father of the House is not necessarily the oldest Member. -

Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism

Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism MARK R. BEISSINGER Abstract This article examines the role of nationalism in the collapse of communism in the late 1980s and early 1990s, arguing that nationalism (both in its presence and its absence, and in the various conflicts and disorders that it unleashed) played an important role in structuring the way in which communism collapsed. Two institutions of international and cultural control in particular – the Warsaw Pact and ethnofederalism – played key roles in determining which communist regimes failed and which survived. The article argues that the collapse of communism was not a series of isolated, individual national stories of resistance but a set of interrelated streams of activity in which action in one context profoundly affected action in other contexts – part of a larger tide of assertions of national sovereignty that swept through the Soviet empire during this period. That nationalism should be considered among the causes of the collapse of communism is not a view shared by everyone. A number of works on the end of communism in the Soviet Union have argued, for instance, that nationalism played only a minor role in the process – that the main events took place within official institutions in Moscow and had relatively little to do with society, or that nationalism was a marginal motivation or influence on the actions of those involved in key decision-making. Failed institutions and ideologies, an economy in decline, the burden of military competition with the United States and instrumental goals of self-enrichment among the nomenklatura instead loom large in these accounts.1 In many narratives of the end of communism, nationalism is portrayed merely as a consequence of communism’s demise, as a phase after communism disintegrated – not as an autonomous or contributing force within the process of collapse itself. -

Electoral Reform in Canada: the Shape of Things to Come an Executive Summary March 2016

Electoral Reform in Canada: The Shape of Things to Come An Executive Summary March 2016 We are committed to ensuring that 2015 will be the last federal election conducted under the first- past- the- post voting system. As part of a national engagement process, we will ensure that electoral reform measures—such as ranked ballots, proportional representation, mandatory voting, and online voting—are fully and fairly studied and considered .... Within 18 months of forming government, we will bring forward legislation to enact electoral reform. —Justin Trudeau, Real Change: A Fair and Open Government ABOUT THIS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Public Services Foundation of Canada and the National Union of Public and General Employees have prepared a comprehensive discussion paper based on a survey of the literature and polling and focus group results, which will be published at a later date. This executive summary provides an overview of the main points without the inclusion of the research, position paper, or polling results. Electoral Reform in Canada: The Shape of Things to Come Executive Summary The Canadian Debate Justin Trudeau promised during the election that this would be the last federal election to use the unfair first-past-the-post (FPTP) system. Although he has indicated that other voting systems would be considered, Trudeau has indicated that his preferred proposal is a version of the single transferable vote (STV) that uses a ranked ballot. His critics say that when STV is used in single member ridings, it is really just an alternative vote (AV) system, also known as an instant run-off system, and the result would be even more unfair in its outcome than FPTP. -

The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by James M. Donahue __________________________ Mark A. Noll, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana April 2015 © Copyright 2015 James M. Donahue IN SEARCH OF A GLOBAL, GODLY ORDER: THE ECUMENICAL MOVEMENT AND THE ORIGINS OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS, 1908-1918 Abstract by James M. Donahue This dissertation traces the origins of the League of Nations movement during the First World War to a coalescent international network of ecumenical figures and Protestant politicians. Its primary focus rests on the World Alliance for International Friendship Through the Churches, an organization that drew Protestant social activists and ecumenical leaders from Europe and North America. The World Alliance officially began on August 1, 1914 in southern Germany to the sounds of the first shots of the war. Within the next three months, World Alliance members began League of Nations societies in Holland, Switzerland, Germany, Great Britain and the United States. The World Alliance then enlisted other Christian institutions in its campaign, such as the International Missionary Council, the Y.M.C.A., the Y.W.C.A., the Blue Cross and the Student Volunteer Movement. Key figures include John Mott, Charles Macfarland, Adolf Deissmann, W. H. Dickinson, James Allen Baker, Nathan Söderblom, Andrew James M. Donahue Carnegie, Wilfred Monod, Prince Max von Baden and Lord Robert Cecil. -

Compassthe DIRECTION for the DEMOCRATIC LEFT

compassTHE DIRECTION FOR THE DEMOCRATIC LEFT MAPPING THE CENTRE GROUND Peter Kellner compasscontents Mapping the Centre Ground “This is a good time to think afresh about the way we do politics.The decline of the old ideologies has made many of the old Left-Right arguments redundant.A bold project to design a positive version of the Centre could fill the void.” Compass publications are intended to create real debate and discussion around the key issues facing the democratic left - however the views expressed in this publication are not a statement of Compass policy. compass Mapping the Centre Ground Peter Kellner All three leaders of Britain’s main political parties agree on one thing: elections are won and lost on the centre ground.Tony Blair insists that Labour has won the last three elections as a centre party, and would return to the wilderness were it to revert to left-wing policies. David Cameron says with equal fervour that the Conservatives must embrace the Centre if they are to return to power. Sir Menzies Campbell says that the Liberal Democrats occupy the centre ground out of principle, not electoral calculation, and he has nothing to fear from his rivals invading his space. What are we to make of all this? It is sometimes said that when any proposition commands such broad agreement, it is probably wrong. Does the shared obsession of all three party leaders count as a bad, consensual error – or are they right to compete for the same location on the left-right axis? This article is an attempt to answer that question, via an excursion down memory lane, a search for clear definitions and some speculation about the future of political debate. -

Mainstream Russian Nationalism and the “State-Civilization” Identity: Perspectives from Below

Nationalities Papers (2021), 49: 1, 89–107 doi:10.1017/nps.2020.8 ARTICLE Mainstream Russian Nationalism and the “State-Civilization” Identity: Perspectives from Below Matthew Blackburn* The Institute of Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Based on more than 100 interviews in European Russia, this article sheds light on the bottom-up dynamics of Russian nationalism. After offering a characterization of the post-2012 “state-civilization” discourse from above, I examine how ordinary people imagine Russia as a “state-civilization.” Interview narratives of inclusion into the nation are found to overlap with state discourse on three main lines: (1) ethno-nationalism is rejected, and Russia is imagined to be a unique, harmonious multi-ethnic space in which the Russians (russkie) lead without repressing the others; (2) Russia’s multinationalism is remembered in myths of peaceful interactions between Russians (russkie) and indigenous ethnic groups (korennyye narodi) across the imperial and Soviet past; (3) Russian culture and language are perceived as the glue that holds together a unified category of nationhood. Interview narratives on exclusion deviate from state discourse in two key areas: attitudes to the North Caucasus reveal the geopolitical-security, post-imperial aspect of the “state- civilization” identity, while stances toward non-Slavic migrants in city spaces reveal a degree of “cultural nationalism” that, while -

Strategic Behavior in Exhaustive Ballot Voting: What Can We Learn from the Fifa World Cup 2018 and 2022 Host Elections?

Daniel Karabekyan STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT VOTING: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE FIFA WORLD CUP 2018 AND 2022 HOST ELECTIONS? BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: ECONOMICS WP BRP 130/EC/2016 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE SERIES: ECONOMICS Daniel Karabekyan2 STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT VOTING: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE FIFA WORLD CUP 2018 AND 2022 HOST ELECTIONS?*3 There are many allegations about whether FIFA world cup host countries were chosen honestly or not. We analyse the results of the FIFA Executive Committee voting and reconstruct the set of possible voting situations compatible with the results of each stage. In both elections, we identify strategic behaviour and then analyse the results for honest voting under all compatible voting situations. For the 2018 FIFA world cup election Russia is chosen for all profiles. For the 2022 elections the result depends on the preferences of the FIFA president Sepp Blatter who served as a tie-breaker. If Sepp Blatter prefers Qatar over South Korea and Japan, then Qatar would have been chosen for all profiles. Otherwise there are the possibility that South Korea or Japan would have been chosen as the 2022 host country. Another fact is that if we consider possible vote buying, then it is shown, that the bribery of at least 2 committee members would have been required to guarantee winning of Russia bid and at least 1 member for Qatar. -

Oral History Transcript T-0217, Interview with David Burbank

ORAL HISTORY T-0217 INTERVIEW WITH DAVID BURBANK INTERVIEWED BY NOEL DARK SOCIALIST PARTY PROJECT NOVEMBER 29, 1972 This transcript is a part of the Oral History Collection (S0829), available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. My name is Noel Clark. I am a graduate student at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. The date is November 29, 1972. I am going to talk this evening to Mr. David Burbank about the Socialist Party in the State of Missouri. CLARK: Mr. Burbank, would you mind, first of all, saying your name? BURBANK: Yes, I am David Burbank. CLARK: ...and your address. BURBANK: My address is 300 Mansion Center, St. Louis. CLARK: Okay. Mr. Burbank, would you mind giving us a short history on the Socialist Party as you first became acquainted with it? BURBANK: Well, I think I might start out by giving a little bit of background. As you probably know, the Socialist Party was greatly reduced after World War I. The Red scares and the Communist split reduced it nationally to very little. There were several cities where they had originally been very strong before World War I and even during World War I. St. Louis was one of them. There was a very large German population and this party here was, to a very large extent, a German organization. It had been so for a long time. The German Socialists were active in various German Unions, like the brewery works, the carpenters, machinists and so on, and exercised considerable influence in these unions. -

Electoral Reform “Regardless of Electoral System, There Will Always

Electoral Reform “Regardless of electoral system, there will always be opposing views as to advantages and disadvantages of each” Submitted by SR-F 06 September 2016 Because elections and referenda require a high level of voter awareness and responsibility, civic participation in governance must be encouraged in order that Canada’s Democracy becomes one that protects liberties, particularly communal liberties, rather than simply emphasizing individual Rights. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hMIbH5D0waA Direct Democracy would be the ideal voting system because it allows citizens to participate in most every aspect of governance through initiatives/voting/referenda... laws and changes to the national constitution being voted on by the citizenry affording them a much greater measure of control over political minutiae. Switzerland is the most prominent modern democracy to use elements of Direct Democracy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voting_in_Switzerland with versions of it at State and local levels in the USA. As opposed to direct democracy, some version of Representative Democracy , founded on the principle of elected officials representing a group of people (includes Referendum/Initiatives/Recall that provide limited Direct Democracy), would appear to be more practical for Canada at this point in time. Present System : FPTP - Plurality In “winner-take-all" electoral systems, generally just two parties end up competing in national elections, forcing political discussions into a narrow two-party frame where loyalty and party line assertions can distort political debate, voters left undecided as to where to place their vote. When FPTP Voters realise that their preferred candidate cannot win, knowing that their vote won’t count or will be wasted, they have little incentive to vote. -

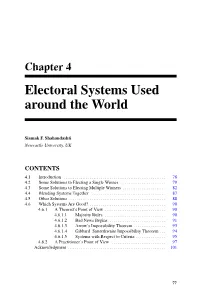

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

I Bitterly Regret the Day I Comgromised the Unity of My Party by Admitting

Scottish Government Yearbook 1990 FACTIONS, TENDENCIES AND CONSENSUS IN THE SNP IN THE 1980s James Mitchell I bitterly regret the day I comgromised the unity of my party by admitting the second member.< A work written over a decade ago maintained that there had been limited study of factional politics<2l. This is most certainly the case as far as the Scottish National Party is concerned. Indeed, little has been written on the party itself, with the plethora of books and articles which were published in the 1970s focussing on the National movement rather than the party. During the 1980s journalistic accounts tended to see debates and disagreements in the SNP along left-right lines. The recent history of the party provides an important case study of factional politics. The discussion highlights the position of the '79 Group, a left-wing grouping established in the summer of 1979 which was finally outlawed by the party (with all other organised factions) at party conference in 1982. The context of its emergence, its place within the SNP and the reaction it provoked are outlined. Discussion then follows of the reasons for the development of unity in the context of the foregoing discussion of tendencies and factions. Definitions of factions range from anthropological conceptions relating to attachment to a personality to conceptions of more ideologically based groupings within liberal democratic parties<3l. Rose drew a distinction between parliamentary party factions and tendencies. The former are consciously organised groupings with a membership based in Parliament and a measure of discipline and cohesion. The latter were identified as a stable set of attitudes rather than a group of politicians but not self-consciously organised<4l. -

Understanding British and European Political Issues Understanding Politics

UNDERSTANDING BRITISH AND EUROPEAN POLITICAL ISSUES UNDERSTANDING POLITICS Series editor DUNCAN WATTS Following the review of the national curriculum for 16–19 year olds, UK examining boards have introduced new specifications for first use in 2001 and 2002. A level courses will henceforth be divided into A/S level for the first year of sixth form studies, and the more difficult A2 level thereafter. The Understanding Politics series comprehensively covers the politics syllabuses of all the major examination boards, featuring a dedicated A/S level textbook and three books aimed at A2 students. The books are written in an accessible, user-friendly and jargon-free manner and will be essential to students sitting these examinations. Already published Understanding political ideas and movements Kevin Harrison and Tony Boyd Understanding American government and politics Duncan Watts Understanding British and European political issues A guide for A2 politics students NEIL McNAUGHTON Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Neil McNaughton 2003 The right of Neil McNaughton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distribued exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 6245 4 paperback First published 2003 111009080706050403 10987654321 Typeset by Northern Phototypesetting Co.