In the Eyes of the Experts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Number Document Title Authors, Compilers, Or Editors Date

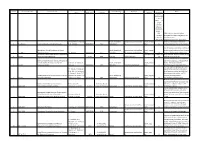

Authors, Compilers, or Date (M/D/Y), Location, Site, or Format/Copy/C Ensure Index # Document Number Document Title Status Markings Keywords Notes Editors (M/Y) or (Y) Company ondition Availability Codes: N=ORNL/NCS; Y=NTIS/ OSTI, J‐ 5700= Johnson Collection‐ ORNL‐Bldg‐ 5700; T‐ CSIRC= ORNL/ Nuclear Criticality Safety Thomas Group,865‐574‐1931; NTIS/OSTI is the Collection, DOE Information LANL/CSIRC. Bridge:http://www.osti.gov/bridge/ J. W. Morfitt, R. L. Murray, Secret, declassified computational method/data report, original, Early hand calculation methods to 1 A‐7.390.22 Critical Conditions in Cylindrical Vessels G. W. Schmidt 01/28/1947 Y‐12 12/12/1956 (1) good N estimate process limits for HEU solution Use of early hand calculation methods to Calculation of Critical Conditions for Uranyl Secret, declassified computational method/data report, original, predict critical conditions. Done to assist 2 A‐7.390.25 Fluoride Solutions R. L. Murray 03/05/1947 Y‐12 11/18/1957 (1), experiment plan/design good N design of K‐343 solution experiments. Fabrication of Zero Power Reactor Fuel Elements CSIRC/Electroni T‐CSIRC, Vol‐ Early work with U‐233, Available through 3 A‐2489 Containing 233U3O8 Powder 4/1/44 ORNL Unknown U‐233 Fabrication c 3B CSIRC/Thomas CD Vol 3B Contains plans for solution preparation, Outline of Experiments for the Determination of experiment apparatus, and experiment the Critical Mass of Uranium in Aqueous C. Beck, A. D. Callihan, R. Secret, declassified report, original, facility. Potentially useful for 4 A‐3683 Solutions of UO2F2 L. Murray 01/20/1947 ORNL 10/25/1957 experiment plan/design good Y benchmarking of K‐343 experiments. -

Bunker Busters: Washington's Drive for New Nuclear Weapons

BRITISH AMERICAN SECURITY INFORMATION COUNCIL BASIC RESEARCH REPORT Bunker Busters: Washington’s Drive for New Nuclear Weapons Mark Bromley, David Grahame and Christine Kucia Research Report 2002.2 July 2002 B U N K E R B U S T E R S British American Security Information Council The British American Security Information Council (BASIC) is an independent research organisation that analyses international security issues. BASIC works to promote awareness of security issues among the public, policy makers and the media in order to foster informed debate on both sides of the Atlantic. BASIC in the UK is a registered charity no. 1001081 BASIC in the US is a non-profit organization constituted under section 501(c)(3) of the US Internal Revenue Service Code. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the many individuals and organisations whose advice and assistance made this report possible. Special thanks go to David Culp (Friends Committee on National Legislation) and Ian Davis for their guidance on the overall research and writing. The authors would also like to thank Martin Butcher (Physicians for Social Responsibility), Nicola Butler, Aidan Harris, Karel Koster (PENN-Netherlands), Matt Rivers, Paul Rogers (Bradford University), and Dmitry Polikanov (International Committee of the Red Cross) for valuable advice on the report. Support This publication was made possible by grants from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Colombe Foundation, Compton Foundation, Inc., The Ford Foundation, W. Alton Jones Foundation, Polden Puckham Charitable Trust, Ploughshares Fund, private support from the Rockefeller Family, and the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Bunker Busters: Washington’s Drive for New Nuclear Weapons By Mark Bromley, David Grahame and Christine Kucia Published by British American Security Information Council July 2002 Price: $10/£7 ISBN: 1 874533 46 6 2 F O R E W O R D Contents Foreword: Ambassador Jonathan Dean .............................................................. -

POLICY BRIEF by George Bunn & John B

ary ald Reagan Libr Courtesy Ron POLICY BRIEF by George Bunn & John B. Rhinelander LAWS September 2007 Reykjavik Revisited: Toward a World Free of Nuclear Weapons It would be fine with At their October 1986 Reykjavik summit meeting, Ronald Reagan me if we eliminated all and Mikhail Gorbachev agreed orally that their two governments should "nuclear weapons. eliminate all their nuclear weapons. Reagan said, “It would be fine with me if we eliminated all nuclear weapons.” Gorbachev replied, “We can do that.” Reagan’s secretary of state, George Shultz, participated in the – Ronald Reagan, discussion. While that proposal later floundered over U.S. plans for October 1986 missile defense and differences over the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) " Treaty, the goal of going to zero nuclear weapons is highly relevant today.1 George Shultz, now at the Hoover Institution on the campus of Stanford University, organized a conference to review the goal of Reykjavik in October 2006, the 20th anniversary of the Reykjavik This policy brief made possible summit. He invited former high-level government officials and other by the Lawyers Alliance for World experts to consider major changes in current U.S. nuclear-weapon control Security, an independent partner and reduction policies, including the ultimate goal of a world free of of the World Security Institute. nuclear weapons. He had the assistance of Sidney Drell, a distinguished Stanford physicist who has long been an adviser to the U.S. government 1 The best treatment of this extraordinary meeting is Don Oberdorfer, The Turn (1991), chap. 5, 155-209, including page 202 for the Reagan- Gorbachev quotes (This has been republished under soft cover under the new title, From The Cold War To A New Era: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1983-1991). -

Nuclear Deterrence in the Information Age?

SUMMER 2012 Vol. 6, No. 2 Commentary Our Brick Moon William H. Gerstenmaier Chasing Its Tail: Nuclear Deterrence in the Information Age? Stephen J. Cimbala Fiscal Fetters: The Economic Imperatives of National Security in a Time of Austerity Mark Duckenfield Summer 2012 Summer US Extended Deterrence: How Much Strategic Force Is Too Little? David J. Trachtenberg The Common Sense of Small Nuclear Arsenals James Wood Forsyth Jr. Forging an Indian Partnership Capt Craig H. Neuman II, USAF Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Mission Statement Commander, Air Education and Training Command Strategic Studies Quarterly (SSQ) is the senior United States Air Force– Gen Edward A. Rice Jr. sponsored journal fostering intellectual enrichment for national and Commander and President, Air University international security professionals. SSQ provides a forum for critically Lt Gen David S. Fadok examining, informing, and debating national and international security Director, Air Force Research Institute matters. Contributions to SSQ will explore strategic issues of current and Gen John A. Shaud, PhD, USAF, Retired continuing interest to the US Air Force, the larger defense community, and our international partners. Editorial Staff Col W. Michael Guillot, USAF, Retired, Editor CAPT Jerry L. Gantt, USNR, Retired, Content Editor Disclaimer Nedra O. Looney, Prepress Production Manager Betty R. Littlejohn, Editorial Assistant The views and opinions expressed or implied in the SSQ are those of the Sherry C. Terrell, Editorial Assistant authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, Air Education Editorial Advisors and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or depart- Gen John A. -

War Prevention Works 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict by Dylan Mathews War Prevention OXFORD • RESEARCH • Groupworks 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict

OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP war prevention works 50 stories of people resolving conflict by Dylan Mathews war prevention works OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP 50 stories of people resolving conflict Oxford Research Group is a small independent team of Oxford Research Group was Written and researched by researchers and support staff concentrating on nuclear established in 1982. It is a public Dylan Mathews company limited by guarantee with weapons decision-making and the prevention of war. Produced by charitable status, governed by a We aim to assist in the building of a more secure world Scilla Elworthy Board of Directors and supported with Robin McAfee without nuclear weapons and to promote non-violent by a Council of Advisers. The and Simone Schaupp solutions to conflict. Group enjoys a strong reputation Design and illustrations by for objective and effective Paul V Vernon Our work involves: We bring policy-makers – senior research, and attracts the support • Researching how policy government officials, the military, of foundations, charities and The front and back cover features the painting ‘Lightness in Dark’ scientists, weapons designers and private individuals, many of decisions are made and who from a series of nine paintings by makes them. strategists – together with Quaker origin, in Britain, Gabrielle Rifkind • Promoting accountability independent experts Europe and the and transparency. to develop ways In this United States. It • Providing information on current past the new millennium, has no political OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP decisions so that public debate obstacles to human beings are faced with affiliations. can take place. nuclear challenges of planetary survival 51 Plantation Road, • Fostering dialogue between disarmament. -

The American-Scandinavian Foundation

THE AMERICAN-SCANDINAVIAN FOUNDATION BI-ANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2011 TO JUNE 30, 2013 The American-Scandinavian Foundation BI-ANNUAL REPORT July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2013 The American-Scandinavian Foundation (ASF) serves as a vital educational and cultural link between the United States and the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. A publicly supported nonprofit organization, the Foundation fosters cultural understanding, provides a forum for the exchange of ideas, and sustains an extensive program of fellowships, grants, internships/training, publishing, and cultural events. Over 30,000 Scandinavians and Americans have participated in its exchange programs over the last century. In October 2000, the ASF inaugurated Scandinavia House: The Nordic Center in America, its headquarters, where it presents a broad range of public programs furthering its mission to reinforce the strong relationships between the United States and the Nordic nations, honoring their shared values and appreciating their differences. 58 PARK AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10016 • AMscan.ORG H.M. Queen Margrethe II H.E. Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson Patrons of Denmark President of Iceland 2011 – 2013 H.E. Tarja Halonen H.M. King Harald V President of Finland of Norway until February, 2012 H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf H.E Sauli Niinistö of Sweden President of Finland from March, 2012 H.R.H. Princess Benedikte H.H. Princess Märtha Louise Honorary of Denmark of Norway Trustees H.E. Martti Ahtisaari H.R.H. Crown Princess Victoria 2011 – 2013 President of Finland,1994-2000 of Sweden H.E. Vigdís Finnbogadóttir President of Iceland, 1980-1996 Officers 2011 – 2012 Richard E. -

Working Paper: Do Not Cite Or Circulate Without Permission

THE COPENHAGEN TEMPTATION: RETHINKING PREVENTION AND PROLIFERATION IN THE AGE OF DETERRENCE DOMINANCE Francis J. Gavin Mira Rapp-Hooper What price should the United States – or any leading power – be willing to pay to prevent nuclear proliferation? For most realists, who believe nuclear weapons possess largely defensive qualities, the price should be small indeed. While additional nuclear states might not be welcomed, their appearance should not be cause for undue alarm. Such equanimity would be especially warrantedWORKING if the state in question PAPER: lacked DO other attributesNOT CITE of power. OR Nuclear acquisition should certainly notCIRCULATE trigger thoughts of WITHOUT preventive militar PERMISSIONy action, a phenomena typically associated with dramatic shifts in the balance of power. The historical record, however, tells a different story. Throughout the nuclear age and despite dramatic changes in the international system, the United States has time and again considered aggressive policies, including the use of force, to prevent the emergence of nuclear capabilities by friend and foe alike. What is even more surprising is how often this temptation has been oriented against what might be called “feeble” states, unable to project other forms of power. The evidence also reveals that the reasons driving this preventive thinking often had more to do with concerns over the systemic consequences of nuclear proliferation, and not, as we might expect, the dyadic relationship between the United States and the proliferator. Factors 1 typically associated with preventive motivations, such as a shift in the balance of power or the ideological nature of the regime in question, were largely absent in high-level deliberations. -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament

NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament: Challenges for the for 10th and Disarmament: Challenges Conference NPT Review Non-proliferation of Nuclear and the Frameworks NATO Research Paper Tim Caughley, with Yasmin Afina International Security Programme | May 2020 NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Challenges for the 10th NPT Review Conference Tim Caughley, with Yasmin Afina with Yasmin Caughley, Tim Chatham House Contents Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 Background 5 3 NATO and the NPT 8 4 NATO: the NPT and the TPNW 15 5 NATO and the TPNW: Legal Issues 20 6 Conclusions 24 About the Authors 28 Acknowledgments 29 1 | Chatham House NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Summary • The 10th five-yearly Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (the NPT) was due to take place in April–May 2020, but has been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. • In force since 1970 and with 191 states parties, the NPT is hailed as the cornerstone of a rules-based international arms control and non-proliferation regime, and an essential basis for the pursuit of nuclear disarmament. But successive review conferences have been riven by disagreement between the five nuclear weapon states and many non-nuclear weapon states over the appropriate way to implement the treaty’s nuclear disarmament pillar. • Although the number of nuclear weapons committed to NATO defence has been reduced by over 90 per cent since the depths of the Cold War, NATO nuclear weapon states, and their allies that depend on the doctrine of extended nuclear deterrence for their own defence, favour continued retention of the remaining nuclear weapons until the international security situation is conducive to further progress on nuclear disarmament. -

Dear Peace and Justice Activist, July 22, 1997

Peace and Justice Awardees 1995-2006 1995 Mickey and Olivia Abelson They have worked tirelessly through Cambridge Sane Free and others organizations to promote peace on a global basis. They’re incredible! Olivia is a member of Cambridge Community Cable Television and brings programming for the local community. Rosalie Anders Long time member of Cambridge Peace Action and the National board of Women’s Action of New Dedication for (WAND). Committed to creating a better community locally as well as globally, Rosalie has nurtured a housing coop for more than 10 years and devoted loving energy to creating a sustainable Cambridge. Her commitment to peace issues begin with her neighborhood and extend to the international. Michael Bonislawski I hope that his study of labor history and workers’ struggles of the past will lead to some justice… He’s had a life- long experience as a member of labor unions… During his first years at GE, he unrelentingly held to his principles that all workers deserve a safe work place, respect, and decent wages. His dedication to the labor struggle, personally and academically has lasted a life time, and should be recognized for it. Steve Brion-Meisels As a national and State Board member (currently national co-chair) of Peace Action, Steven has devoted his extraordinary ability to lead, design strategies to advance programs using his mediation skills in helping solve problems… Within his neighborhood and for every school in the city, Steven has left his handiwork in the form of peaceable classrooms, middle school mediation programs, commitment to conflict resolution and the ripping effects of boundless caring. -

Assuring South Korea and Japan As the Role and Number of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Are Reduced

Assuring South Korea and Japan as the Role and Number of U.S. Nuclear Weapons are Reduced Michael H. Keifer, Project Manager Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Defense Threat Reduction Agency Prepared by Kurt Guthe Thomas Scheber National Institute for Public Policy January 2011 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. This report is approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office Report Number ASCO 2011 003 Contract Number MIPR 10-2621M The mission of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) is to safeguard America and its allies from weapons of mass destruction (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high explosives) by providing capabilities to reduce, eliminate, and counter the threat, and mitigate its effects. The Advanced Systems and Concepts Office (ASCO) supports this mission by providing long-term rolling horizon perspectives to help DTRA leadership identify, plan, and persuasively communicate what is needed in the near term to achieve the longer-term goals inherent in the agency’s mission. ASCO also emphasizes the identification, integration, and further development of leading strategic thinking and analysis on the most intractable problems related to combating weapons of mass destruction. For further information on this project, or on ASCO’s broader research program, please contact: Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office 8725 John J. Kingman Road Ft. Belvoir, VA 22060-6201 [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction...................................................................................................................... -

Winter 2020 Full Issue

Naval War College Review Volume 73 Number 1 Winter 2020 Article 1 2020 Winter 2020 Full Issue The U.S. Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The U.S. (2020) "Winter 2020 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 73 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol73/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Winter 2020 Full Issue Winter 2020 Volume 73, Number 1 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2020 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 73 [2020], No. 1, Art. 1 Cover Two modified Standard Missile 2 (SM-2) Block IV interceptors are launched from the guided-missile cruiser USS Lake Erie (CG 70) during a Missile Defense Agency (MDA) test to intercept a short-range ballistic-missile target, conducted on the Pacific Missile Range Facility, west of Hawaii, in 2008. The SM-2 forms part of the Aegis ballistic-missile defense (BMD) program. In “A Double-Edged Sword: Ballistic-Missile Defense and U.S. Alli- ances,” Robert C. Watts IV explores the impact of BMD on America’s relationship with NATO, Japan, and South Korea, finding that the forward-deployed BMD capability that the Navy’s Aegis destroyers provide has served as an important cement to these beneficial alliance relationships.