Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-Accented English: a Phonetic Comparison

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp. 724-738, September 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1105.07 Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-accented English: A Phonetic Comparison Yunyun Ran School of Foreign Languages, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, 333 Long Teng Road, Shanghai 201620, China Jeroen van de Weijer School of Foreign Languages, Shenzhen University, 3688 Nan Hai Avenue, Shenzhen 518060, China Marjoleine Sloos Fryske Akademy (KNAW), Doelestrjitte 8, 8911 DX Leeuwarden, The Netherlands Abstract—Hong Kong English is to a certain extent a standardized English variety spoken in a bilingual (English-Cantonese) context. In this article we compare this (native) variety with English as a foreign language spoken by other Cantonese speakers, viz. learners of English in Guangzhou (mainland China). We examine whether the notion of standardization is relevant for intonation in this case and thus whether Hong Kong English is different from Cantonese English in a wider perspective, or whether it is justified to treat Hong Kong English and Cantonese English as the same variety (as far as intonation is concerned). We present a comparison between intonational contours of different sentence types in the two varieties, and show that they are very similar. This shows that, in this respect, a learned foreign-language variety can resemble a native variety to a great extent. Index Terms—Hong Kong English, Cantonese-accented English, intonation I. INTRODUCTION Cantonese English may either refer to Hong Kong English (HKE), or to a broader variety of English spoken in the Cantonese-speaking area, including Guangzhou (Wong et al. -

Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: Morphology and Syntax*

Breaking Down the Barriers, 785-816 2013-1-050-037-000234-1 Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: * Morphology and Syntax Hilary Chappell (曹茜蕾) EHESS In Chinese languages, when a direct object occurs in a non-canonical position preceding the main verb, this SOV structure can be morphologically marked by a preposition whose source comes largely from verbs or deverbal prepositions. For example, markers such as kā 共 in Southern Min are ultimately derived from the verb ‘to accompany’, pau11 幫 in many Huizhou and Wu dialects is derived from the verb ‘to help’ and bǎ 把 from the verb ‘to hold’ in standard Mandarin and the Jin dialects. In general, these markers are used to highlight an explicit change of state affecting a referential object, located in this preverbal position. This analysis sets out to address the issue of diversity in such object-marking constructions in order to examine the question of whether areal patterns exist within Sinitic languages on the basis of the main lexical fields of the object markers, if not the construction types. The possibility of establishing four major linguistic zones in China is thus explored with respect to grammaticalization pathways. Key words: typology, grammaticalization, object marking, disposal constructions, linguistic zones 1. Background to the issue In the case of transitive verbs, it is uncontroversial to state that a common word order in Sinitic languages is for direct objects to follow the main verb without any overt morphological marking: * This is a “cross-straits” paper as earlier versions were presented in turn at both the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, during the joint 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics and 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics, held in Taipei in May 25-29, 2006 and also at an invited seminar at the Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing on 23rd October 2006. -

Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia Were Not the Descendants of Yan Huang

E-Leader Brno 2019 Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia were not the Descendants of Yan Huang Soleilmavis Liu, Activist Peacepink, Yantai, Shandong, China Many Chinese people claimed that they are descendants of Yan Huang, while claiming that they are descendants of Hua Xia. (Yan refers to Yan Di, Huang refers to Huang Di and Xia refers to the Xia Dynasty). Are these true or false? We will find out from Shanhaijing ’s records and modern archaeological discoveries. Abstract Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas ) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Yan Di, Huang Di, Zhuan Xu, Di Jun and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of groups, but also the names of individuals, who were regarded by many groups as common male ancestors. These groups first lived in the Pamirs Plateau, soon gathered in the north of the Tibetan Plateau and west of the Qinghai Lake and learned from each other advanced sciences and technologies, later spread out to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. The Yan Di’s offspring spread out to the west of the Taklamakan Desert;The Huang Di’s offspring spread out to the north of the Chishui River, Tianshan Mountains and further northern and northeastern areas;The Di Jun’s and Shao Hao’s offspring spread out to the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, where the Di Jun’s offspring lived in the west of the Shao Hao’s territories, which were near the sea or in the Shandong Peninsula.Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. -

Year 10 Inter-Dynasty Swim Heat Results

Year 10 Inter-Dynasty Swim Heat Results Year 10 Boys 100M Breaststroke Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 01:25.00 2 HAN HA Matthew 01:32.00 3 MING LIANG Brendan 01:33.00 4 TANG HO Yin Ting 01:54.00 5 SONG CHENG Jeremy 02:01.00 6 QING MANN Daniel 02:02.00 7 YUAN ISMAIL Amaan 02:14.00 Year 10 Boys 100M Freestyle Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 01:02.00 2 TANG GRANTHAM Ethan 01:04.00 3 YUAN SIMONE Tommaso 01:06.00 4 QING DALE Rafferty 01:06.72 5 HAN XU Bruce 01:27.00 6 HAN LING Hiu Hong Felix 01:55.35 7 SONG BUDDLE Elliot 01:57.09 Year 10 Boys 50M Backstroke Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 00:36.97 2 TANG TAM Sau Ching 00:37.31 3 HAN LI Edward 00:38.37 4 MING WONG Matthew 00:40.13 5 TANG SAXENA Shaurya 00:43.37 6 SONG LACY Robert 00:49.05 7 QING GUPTA Shrey 01:27.04 Year 10 Boys 50M Butterfly Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 MING WONG Ernest 00:32.21 2 TANG GRANTHAM Ethan 00:32.47 3 HAN LI Edward 00:34.85 4 YUAN SIMONE Tommaso 00:35.22 5 HAN DONEUX Adrien 00:36.50 6 QING KU Christopher 00:55.00 7 SONG GURNANI Vinay 01:00.95 Year 10 Boys 50M Freestyle Place Dynasty Surname First Name Time 1 TANG GRANTHAM Ethan 00:29.56 2 YUAN MIYAGAWA Tatsu 00:30.15 3 HAN LI Edward 00:30.28 Year 10 Inter-Dynasty Swim Heat Results 4 TANG TAM Sau Ching 00:30.75 5 QING DALE Rafferty 00:31.19 6 TANG SAXENA Shaurya 00:32.29 7 HAN DONEUX Adrien 00:32.53 8 MING WONG Matthew 00:33.12 9 MING WONG Ernest 00:33.34 10 MING LIANG Brendan 00:33.75 11 YUAN RUDICO Francis 00:34.62 12 QING DONALD -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Download Our Latest Allegravita Backgrounder Booklet Here (PDF)

Name: Allegravita is an award-winning, multi- disciplinary public relations and strategic communications agency focused on supporting international clients in the China region and taking Chinese clients to the world. We were voted China's most entrepreneurial company by the Australian Chambers of ABOUT ALLEGRAVITA Commerce in China in 2008. Allegravita is a boutique global agency A PORTFOLIO OF SERVICES TO BORN IN CHINA, with personnel and offices in Beijing, HELP YOU SUCCEED IN CHINA EFFECTIVE WORLDWIDE Guangzhou, Kunming, Hong Kong, Public Relations for proactive and Although our focus is on the China New York City and San Francisco. Since reactive messaging. region, our services are very effective 2003 we have provided high-quality Marketing and Communications in markets worldwide, with proven PR, marketing and corporate advisory Collateral to present your messages outcomes. Allegravita works within services with a special focus on achiev- with excellent credibility. a highly-accountable and disciplined ing excellent results for international Media Relations & Media Training Western management style, executing clients in the China region and in Chi- to insert your messages into Chinese the highest quality of work for our nese speaking markets worldwide, and and international media in the most clients, which we deliver with agility, international results for our Chinese compelling way possible. flexibility, creativity and cultural savvy. clients. Corporate Identity localization to Allegravita is an ethnically diverse, We incorporate expert public relations communicate your brand values and multi-cultural team of professionals abilities with a firm grasp of contempo- benefits to Chinese markets, and for of different cultural heritages. What rary China-region marketplaces to help Chinese clients, to international inves- we share in common is our passion for our clients communicate effectively, tors and influencers. -

The Significance and Inheritance of Huang Di Culture

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 8, No. 12, pp. 1698-1703, December 2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0812.17 The Significance and Inheritance of Huang Di Culture Donghui Chen Henan Academy of Social Sciences, Zhengzhou, Henan, China Abstract—Huang Di culture is an important source of Chinese culture. It is not mechanical, still and solidified but melting, extensible, creative, pioneering and vigorous. It is the root of Chinese culture and a cultural system that keeps pace with the times. Its influence is enduring and universal. It has rich connotations including the “Root” Culture, the “Harmony” Culture, the “Golden Mean” Culture, the “Governance” Culture. All these have a great significance for the times and the realization of the Great Chinese Dream, therefore, it is necessary to combine the inheritance of Huang Di culture with its innovation, constantly absorb the fresh blood of the times with a confident, open and creative attitude, give Huang Di culture a rich connotation of the times, tap the factors in Huang Di culture that fit the development of the modern times to advance the progress of the country and society, and make Huang Di culture still full of vitality in the contemporary era. Index Terms—Huang Di, Huang Di culture, Chinese culture I. INTRODUCTION Huang Di, being considered the ancestor of all Han Chinese in Chinese mythology, is a legendary emperor and cultural hero. His victory in the war against Emperor Chi You is viewed as the establishment of the Han Chinese nationality. He has made great many accomplishments in agriculture, medicine, arithmetic, calendar, Chinese characters and arts, among which, his invention of the principles of Traditional Chinese medicine, Huang Di Nei Jing, has been seen as one of the greatest contributions to Chinese medicine. -

Cifu: a Frequency Lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 3069–3077 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Cifu: a frequency lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese Regine Lai, Grégoire Winterstein The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Université du Québec à Montréal Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, Département de Linguistique [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper introduces Cifu, a lexical database for Hong Kong Cantonese (HKC) that offers phonological and orthographic information, frequency measures, and lexical neighborhood information for lexical items in HKC. The resource can be used for NLP applications and the design and analysis of psycholinguistic experiments on HKC. We elaborate on the characteristics and challenges specific to HKC that were relevant in the design of Cifu. This includes lexical, orthographic and phonological aspects of HKC, word segmentation issues, the place of HKC in written media, and the availability of data. We discuss the measure of Neighborhood Density (ND), highlighting how the analytic nature of Cantonese and its writing system affect that measure. We justify using six different variations of ND, based on the possibility of inserting or deleting phonemes when searching for neighbors and on the choice of data for retrieving frequencies. Statistics about the four genres (written, adult spoken, children spoken and child-directed) within the dataset are discussed. We find that the lexical diversity of the child-directed speech genre is particularly low, compared to a size-matched written corpus. The correlations of word frequencies of different genres are all high, but in general decrease as word length increases. -

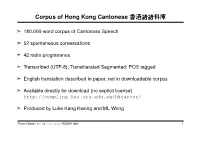

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港港港語語語語語語料料料庫庫庫

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港nn;;;;;;$$$庫庫庫 ã 180,000-word corpus of Cantonese Speech ã 52 spontaneous conversations ã 42 radio programmes ã Transcribed (UTF-8); Transliterated Segmented; POS tagged ã English translation described in paper, not in downloadable corpus ã Available directly for download (no explicit license) http://compling.hss.ntu.edu.sg/hkcancor/ ã Produced by Luke Kang Kwong and ML Wong Francis Bond <[email protected]> HG3051 lab2 1 Creation ã 30 hours of recordings (March 1997 — August 1998) ã Native speakers of Cantonese ã ordinary settings with family members, friends and colleagues talking with each other freely on everyday topics such as current affairs, work and study, and personal hobbies ã Some parts selected 2 Meta-Data/Annotation ã Meta-Data Tape number (of recording); Date of recording Number of Speakers; List of Speakers (Code-Sex-Age-Origin) (e.g. A-M-22-HK says A is a 22-year-old male speaker from Hong Kong) ã Annotation Each Utterance has the speaker code Utterances are segmented, POS tagged and transliterated Ç%h/d/ge3i1bun2soeng6/ 2個/r/ni1go3/ze ... ã The whole corpus is wrapped in xml (but not very well) 3 Usage ã Used to examine the uses of the frequently used sentence final particles woˇ and boˇ in the 1990s in Hong Kong Cantonese by examining speech data. ã Question: are woˇ (喎) and boˇ (S) variant forms? ã Answer: No “[. ] the two SFPs carry and serve different meanings and functions in modern Hong Kong Cantonese, and thus they are not exactly the same particles and not interchangeable as previously assumed.” (Leung, 2010, p21) ã Also used as a corpus in the PyCantonese Project: Working with Cantonese corpus data using Python, by Jackson L. -

Hannah Arendt's Question and Human Rights Debates in Mao's

Human Rights and Their Discontents: Hannah Arendt’s Question and Human Rights Debates in Mao’s China Wenjun Yu Human Rights and Their Discontents: Hannah Arendt’s Question and Human Rights Debates in Mao’s China Het onbehagen over mensenrechten: het probleem van Hannah Arendt en het debat over mensenrechten in het China van Mao (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 4 juli 2017 des middags te 12.45 uur door Wenjun Yu geboren op 3 april 1986 te Hubei, China Promotor: Prof.dr. I. de Haan Acknowledgements Writing a PhD dissertation is not a lonely work, I cannot finish this job without the generous help and supports from my supervisor, fellow PhD students, colleagues, friends and family. Although I take the complete responsibility for the content of this dissertation, I would like to thank all accompanies for their inspiration, encouragement, and generosity in the course of my PhD research. First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Ido de Haan for his continuous support of my PhD work at Utrecht University, for his great concern over my life in the Netherlands, for his generous encouragements and motivations when I was frustrated by many research problems, and particularly when I was stuck in the way of writing the dissertation during my pregnancy and afterwards. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use.