'Our Pier': Leisure Activities and Local Communities at the British Seaside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

The Future of Seaside Towns

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 Thursday 04 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities Report of Session 2017–19 The future of seaside towns STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01am Thursday 4 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. Ordered to be printed 19 March 2019 and published 4 April 2019 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 320 STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 Thursday 04 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities The Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities was appointed by the House of Lords on 17 May 2018 “to consider the regeneration of seaside towns and communities”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities were: Baroness Bakewell (from 6 September) Lord Mawson Lord Bassam of Brighton (Chairman) Lord Pendry (until 18 July 2018) Lord Grade of Yarmouth Lord Shutt of Greetland Lord Knight of Weymouth Lord Smith of Hindhead The Bishop of Lincoln Baroness Valentine Lord Lucas Baroness Whitaker Lord McNally Baroness Wyld Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. -

Accessibility Guide.Pdf

Accessibility Guide We want to make everyone's visit as enjoyable as possible and are committed to providing suitable access for all our guests, whatever their individual needs we 1 endeavour to offer the same high quality service. We aim to accurately describe our facilities and services below to give you as much information as possible before booking your visit. Specific accessibility enquiries please contact the owners direct: Stuart 07713211132 Zoe 07980808096 Email: [email protected] Owners can be contacted 24 hours a day. Getting here St Annes Beach Huts, The Island, South Promenade, Lytham St Annes Annes, Lancashire FY8 1LS By car Take the M6 motorway to junction 32 and follow the M55 signposted Blackpool. At the end of the motorway follow signs to South Shore/Lytham St Annes, proceeding past Blackpool Airport. Follow the seafront road all the way heading to Lytham St Annes. Take the 1st right after St Annes Pier onto the Island Cinema seafront car park by the RNLI shop. This is Pay & Display (except for a few spaces marked with red and blue lines immediately in front of the cinema building) By Taxi You can get a taxi with Whiteside Taxis by calling 01253 711611. The taxi company has a wheelchair accessible vehicle. You can get a taxi with Premier Cabs by calling 01253 711111. The taxi company has a wheelchair accessible vehicle. By train Trains run on a hourly basis from Preston Mainline station to St Annes. There is a taxi rank outside St Annes Station, although, if you prefer to walk, the Beach Huts are just 10 – 15 minutes away. -

Simon Robertshas Photographed Every British Pleasure Pier There Is

Simon Roberts has photographed every British pleasure pier there is – and several that there aren’t. Overleaf, Francis Hodgson celebrates this devotion to imperilled treasures 14 15 here are 58 surviving pleasure piers in Britain and Simon Roberts has photographed them all. He has also photographed some of the vanished ones, as you can see from his picture of Shanklin Pier on the Isle of Wight (on page 21), destroyed in the great storm which did so much damage in southern England on October 16, 1987. Roberts is a human geographer by training, and his study of piers is a natural development of his previous major work, We English, which looked at the changing patterns of leisure in a country in which a rising population and decreasing mass employment mean that more of us have more time upon our hands than ever before. We tend to forget that holidays are a relatively new phenomenon, but it was only after the Bank Holiday Act of 1871 that paid leave gradually became the norm, and cheap, easily reachable leisure resorts a necessity. Resorts were commercial propositions, and the pier was often a major investment to draw crowds. Consortia of local businessmen would get together to provide the finance and appoint agents to get the thing Previous page done: a complex chicane of lobbying for private spans English Channel legislation, engineering, and marketing. Around design Eugenius Birch construction Raked the same time, a number of Acts made it possible and vertical cast iron screw to limit liability for shareholders in speculative piles supporting lattice companies. -

Pier Pressure: Best Practice in the Rehabilitation of British Seaside Piers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Pier pressure: Best practice in the rehabilitation of British seaside piers A. Chapman Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK ABSTRACT: Victorian seaside piers are icons of British national identity and a fundamental component of seaside resorts. Nevertheless, these important markers of British heritage are under threat: in the early 20th century nearly 100 piers graced the UK coastline, but almost half have now gone. Piers face an uncertain future: 20% of piers are currently deemed ‘at risk’. Seaside piers are vital to coastal communities in terms of resort identity, heritage, employment, community pride, and tourism. Research into the sustainability of these iconic structures is a matter of urgency. This paper examines best practice in pier regeneration projects that are successful and self-sustaining. The paper draws on four case studies of British seaside piers that have recently undergone, or are currently being, regenerated: Weston Super-Mare Grand pier; Hastings pier; Southport pier; and Penarth pier. This study identifies critical success factors in pier regeneration and examines the socio-economic sustainability of seaside piers. 1 INTRODUCTION This paper focuses on British seaside piers. Seaside pleasure piers are an uniquely British phenomena, being developed from the early 19th century onwards as landing jetties for the holidaymakers arriving at the resorts via paddle steamers. As seaside resorts developed, so too did their piers, transforming by the late 19th century into places for middle-class tourists to promenade, and by the 20th century as hubs of popular entertainment: the pleasure pier. -

BRSUG Number Mineral Name Hey Index Group Hey No

BRSUG Number Mineral name Hey Index Group Hey No. Chem. Country Locality Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-37 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Basset Mines, nr. Redruth, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-151 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Phoenix mine, Cheese Wring, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-280 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 County Bridge Quarry, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and South Caradon Mine, 4 miles N of Liskeard, B-319 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-394 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 ? Cornwall? Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-395 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-539 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Houghton, Michigan Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-540 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-541 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, -

Pier Pressure © Rory Walsh

Viewpoint Pier pressure © Rory Walsh Time: 15 mins Region: East of England Landscape: coastal Location: Southend Pier, Western Esplanade, Southend-on-Sea, Essex SS1 1EE Grid reference: TQ 88486 84941 Keep an eye out for: Wading birds and the masts of a wrecked Second World War ship, the SS Richard Montgomery 1.3 miles, 2.2 kilometres, 2,158 metres, 7,080 feet – however you measure it, Southend’s pleasure pier is the longest in the world. On hot days walking to the end can feel like making a pilgrimage to the sun. No wonder most of the pier’s 200,000 annual visitors hop aboard one of the special trains. From this proud symbol of Britain’s seaside you can enjoy sweeping views across the Essex Estuary, sample various amusements and send a postcard from the pier’s own letterbox. Why does Southend have the world’s longest pleasure pier? To begin let’s think about where we are. Southend Pier is in Southend-on-Sea. The ‘on-Sea’ part is an important reminder of why piers were built. Today most of us enjoy them from dry land but they were originally for travelling on water. Piers developed for docking boats. Landing at Southend is difficult though. If you are here at low tide, look for small boats stranded on sheets of mud. The water retreats a mile from the seafront. Even at high tide the sea is never deeper than six metres, so large boats can’t dock near the beach. If landing here was so much trouble, why go through the time and expense of building a huge pier? It’s no coincidence that many of Britain’s seaside piers date from the early 19th century. -

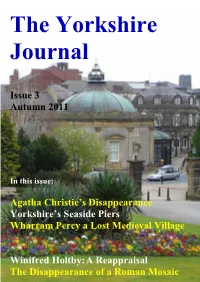

Issue 3 Autumn 2011 Agatha Christie's Disappearance

The Yorkshire Journal Issue 3 Autumn 2011 In this issue: Agatha Christie’s Disappearance Yorkshire’s Seaside Piers Wharram Percy a Lost Medieval Village Winifred Holtby: A Reappraisal The Disappearance of a Roman Mosaic Withernsea Pier Entrance Towers Above: All that remain of the Withernsea Pier are the historic entrance towers which were modelled on Conwy Castle. The pier was built in 1877 at a cost £12,000 and was nearly 1,200 feet long. The pier was gradually reduced in length through consecutive impacts by local sea craft, starting with the Saffron in 1880 then the collision by an unnamed ship in 1888. Then following a collision with a Grimsby fishing boat and finally by the ship Henry Parr in 1893. This left the once-grand pier with a mere 50 feet of damaged wood and steel. Town planners decided to remove the final section during sea wall construction in 1903. The Pier Towers have recently been refurbished. In front of the entrance towers is a model of how the pier would have once looked. Left: Steps going down to the sands from the entrance towers. 2 The Yorkshire Journal TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 3 Autumn 2011 Above: Early autumn in the village of Burnsall in the Yorkshire Dales, which is situated on the River Wharfe with a five-arched bridge spanning it Cover: The Royal Pump Room Museum, Harrogate Editorial n this autumn issue we look at some of the things that Yorkshire has lost, have gone missing and disappeared. Over the year the Yorkshire coast from Flamborough Head right down to the Humber estuary I has lost about 30 villages and towns. -

Wsm & Wells Days out By

Sand Bay Sand Bay Holiday Park S Water Adventure B a Your local buses... n d Routes for amazing d a o R R o Visit amazing beaches... & Play Park a h Kewstoke d c a Open April-September the e days out by bus... B Weston-super-Mare to park has fountains and 1 Ln n Weston-super-Mare 1 Birnbeck Pier • Sand Bay sprays triggered by sensors to or N and buttons and costs Hazelwood er w The main beach area lies south of The Grand Pier £2.50 per child until August Caravan Park Lo Kewstoke and during the summer season visitors flock here Let’s get there together. C Jump on an open top bus for amazing views on a trip along the coast. and is free in September. Ln Village kes r to sunbathe, build sandcastles and partake in all oo o Cr o The play park is open all d k Hop off at Sand Bay and take a walk along the large and relatively wild a e the traditional Great British seaside activities. The o s R L year round and is free. n beach before returning to all that Weston-super-Mare has to offer. h Uphill Sands section of the beach is partitioned c a e off for kitesurfing and other watersports. visit-westonsupermare.com B When do the buses run? Journey time from Weston M Kewstoke o (8.30am- n Every 30 mins Mon-Sat 18 mins to Sand Bay. oad Toll Gate k e R s ok t H Brean ews 5.30pm), 60 mins on Sun. -

Paddle Steamer Waverley for a Great Day out August 28 Until October 7, 2018

Step aboard Paddle Steamer Waverley for a great day out August 28 until October 7, 2018 Day, Afternoon & Evening Cruises Sailing from Liverpool & Llandudno, Clevedon, Penarth, Ilfracombe, Minehead, Swansea, Southampton, Portsmouth, Isle of Wight, Dorset, London, Gravesend, Southend, Essex, Sussex & Kent Resorts Welcome Aboard Waverley is the last seagoing Paddle Steamer in the World! Owned by a Charity and magnificently restored with towering funnels, timber decks, gleaming varnish and brass – see and hear the mighty engines turn the ship’s famous paddles! This year you can visit the Victorian town of Llandudno or cruise the magnificent Anglesey Coast.Explore the coasts and rivers of the Bristol Channel - visit Ilfracombe or Lundy Island. Take a cruise along the Jurassic Coast - see the famous Needles & Lulworth Cove or visit one of the charming seaside towns on the South Coast. Explore the River Thames and watch as London’s Tower Bridge opens especially for you! 2 Book online at waverleyexcursions.co.uk Contents Sailings from Liverpool & Llandudno 4 What to See & Do on the Bristol Channel 5 Sailings from Penarth, Swansea & Porthcawl 6 Sailings from Ilfracombe & Minehead 6 Sailings from Clevedon 6 What to See & Do on the South Coast 8 Sailings from Southampton & Portsmouth 9 Connect from Worthing 9 Sailings from Weymouth & Swanage 10 Sailings from Isle of Wight 11 Sailings from Southend & Clacton 12 Sailing from Harwich 12 Sailings from Whitstable 12 Connect from Margate 12 Sailings from London & Gravesend 13 Connect from Southwold 14 Connect from Great Yarmouth & Ipswich 14 What to See & Do on the Thames 15 Dine with a drink in one of the restored period lounges, or simply watch the world slip by as you enjoy breathtaking views. -

Hastings Pier

FEBRUARY 2018 THEJCT JCT CONTRACTS UPDATE FORNEWS THE CONSTRUCTION PROFESSIONAL HASTINGS PIER A devastating fire in 2010 destroyed 90% of the fell into a state of disrepair, as piers across the the pier project to pass to the Hastings Pier super-structure of Hastings Pier, leaving only country became generally less fashionable. Charity. A development plan was submitted the western pavilion building salvageable. With The pier was closed in 2008. Throughout this to the Heritage Lottery Fund, who granted funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the period, the local community campaigned for the £11.4m towards the total £15m project cost. local community, the opportunity was taken to Grade II listed structure to be saved, but plans The remaining funds were raised through redefine the role of a pier for the 21st Century. were changed dramatically when the fire in a community scheme, which raised over The fabulous result – which won the RIBA 2010 devastated so much of the structure. £600,000, and a number of donations. London- Stirling Prize in 2017 – was built on a JCT Minor based architect dRMM won the competition In 2012 a compulsory purchase order obtained Works Building Contract. to design the project and made the decision by Hastings Council allowed ownership of Hastings Pier’s history goes back to 1872 as a classic, Victorian style, pier designed by Eugenius Birch and built for a cost of £23,250. Numerous additions and features were added to the original construction, including a building housing a shooting gallery, ‘animated pictures’, slot machine, and rifle range/bowling alley. -

Historical Overview of Hastings

Historical Overview of Hastings Hastings Pier, reopened in 2016, HPC014.034 www.hastingspier.org.uk 1 Historical Overview of Hastings by Decade Pre-Victorian/1872 Hastings was already a popular seaside resort in the late 18th century, and King George III's physician, Dr Baillie, recommended it to his patients. The Pigot & Co Directory for 1840 commented that Hastings had "the most excellent accommodations for sea bathing and that the recreations were in every respect worthy of this fashionable town". Victorian Era “Hastings & St Leonards Pier. This noble structure, which extends 900 feet from the parade, was opened on the 5th August, 1872, with great ceremony by Earl Granville, K.G., Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. The Pier is 40 feet wide. At the head or southern end, stands the pavilion, capable of seating nearly 1500 persons. A fine band plays three times daily. During the summer months, vocal and instrumental concerts are given daily, and in the winter months’ variety entertainments every evening. It was built by Messrs. Laidlaw & Sons, under the Superintendence of the Engineer, Mr. Birch.Secretary, Mr. S. T. Weston, 3, Havelock Road, Hastings. Pier Master Mr. W.C. Lenton.” From the Hastings & St Leonards Advertiser 1887 Starting in the 1840s, the new railway system enabled thousands of ordinary people to reach the seaside easily. Newly accessible resort towns sprang up along Britain's coastline. In 1820, it took six hours to travel from London to the coast, but by 1862 only two hours. Factory workers and clerks escaped smokey cities to enjoy the fresh sea air.