'Pierdom' by Simon Roberts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herne Bay Historical Re Erne Bay Historical Records Society Ical Records Society

Herne Bay Historical Records Society Founded 1932 Registered Charity No. 1148803 Custodian s of the Town’s Archive Quarterly Newsletter Autumn 2017 Issue No. 7 Welcome Contents Society News HBHRS Members update 1 Heritage Centre Progress The tale of the Chemist’s drawers 2 Our Heritage Centre at number 81 Central Parade Policing in Herne Bay – Part 3 3 has now been open nearly six months. It is The rise and fall of Henry Corbett Jones – Part 1 4 pleasing to see the progress that has taken place Changes in Avenue Road 7 and during this time and so far we have received Pier Diving at Herne Bay 8 many favourable comments. Margaret has headed Image Gallery 10 up a small, but loyal team of volunteers who have Society Contacts 11 ensured that the centre has been open each Society Publications 11 Wednesday and Saturday. So far, we have Ev ents and dates for your diary 12 exceeded 1,000 visitors, far more than we anticipated. Part of the Remembrance window display . We are grateful to Mick Hill s for building a shelf Part of the wall display inside the Heritage Centre. unit in the small front window. This has enabled us It would be great to engage the help of a few more to start using this for topical displays and I hope of our members, so if you are able to spare an that readers will have seen the tasteful War hour or two on a regular basis, please contact Memorial that Margaret has put together for this either Margaret or John. -

Download Network

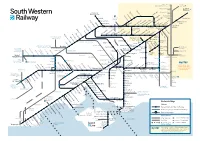

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

The Future of Seaside Towns

STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 Thursday 04 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities Report of Session 2017–19 The future of seaside towns STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01am Thursday 4 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. Ordered to be printed 19 March 2019 and published 4 April 2019 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 320 STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01 Thursday 04 April 2019 You must not disclose this report or its contents until the date and time above; any breach of the embargo could constitute a contempt of the House of Lords. Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities The Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities was appointed by the House of Lords on 17 May 2018 “to consider the regeneration of seaside towns and communities”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on Regenerating Seaside Towns and Communities were: Baroness Bakewell (from 6 September) Lord Mawson Lord Bassam of Brighton (Chairman) Lord Pendry (until 18 July 2018) Lord Grade of Yarmouth Lord Shutt of Greetland Lord Knight of Weymouth Lord Smith of Hindhead The Bishop of Lincoln Baroness Valentine Lord Lucas Baroness Whitaker Lord McNally Baroness Wyld Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. -

Ryde Esplanade

17 May until late Summer 2021 BUS REPLACEMENT SERVICE , oad t sheaf Inn enue recourt splanade Av fo on Stree ading andown Ryde E Ryde Br S Lake Shanklin Bus Station St Johns R The Wheat The Broadway The Shops Station Monkt Station Ryde Pier Head by Jubilee Place Isle of Wight Steam Railway Sandown Sandown Bay Revised Timetable – ReplacementGrove R oadBus ServiceAcademy Monday Ryde Pier 17 Head May - untilRyde Esplanadelate Summer - subject 2021 to Wightlink services operating RydeRyde Pier Esplanade Head to -Ryde Ryde Esplanade St Johns Road - Brading - Sandown - Lake - Shanklin RydeBuses Esplanaderun to the Isle to of ShanklinWight Steam Railway from Ryde Bus Station on the hour between 1000 - 1600 SuX SuX SuX SuX Ryde Pier Head 0549 0607 0628 0636 0649 0707 0728 0736 0749 0807 0828 0836 0849 0907 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 0552 0610 0631 0639 0652 0710 0731 0739 0752 0810 0831 0839 0852 0910 Ryde Pier Head 0928 0936 0949 1007 1028 1036 1049 1107 1128 1136 1149 1207 1228 1236 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 0931 0939 0952 1010 1031 1039 1052 1110 1131 1139 1152 1210 1231 1239 Ryde Pier Head 1249 1307 1328 1336 1349 1407 1428 1436 1449 1507 1528 1536 1549 1607 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 1252 1310 1331 1339 1352 1410 1431 1439 1452 1510 1531 1539 1552 1610 Ryde Pier Head 1628 1636 1649 1707 1728 1736 1749 1807 1828 1836 1849 1907 1928 1936 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 1631 1639 1652 1710 1731 1739 1752 1810 1831 1839 1852 1910 1931 1939 Ryde Pier Head 1949 2007 2028 2036 2049 2128 2136 2149 2228 2236 2315 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 1952 2010 -

Southport Bid

November 2014 SOUTHPORT BID SOUTHPORT DESTINATION SURVEY 2014 NORTH WEST RESEARCH North West Research, operated by: The Liverpool City Region Local Enterprise Partnership 12 Princes Parade Liverpool, L3 1BG 0151 237 3521 North West Research This study has been produced by the in-house research team at the Liverpool City Region Local Enterprise Partnership. The team produces numerous key publications for the area, including the annual Digest of Tourism Statistics, in addition to collating key data and managing many regular research projects such as Hotel Occupancy and the Merseyside Visitor Survey. Under the badge of North West Research (formerly known as England‟s Northwest Research Service) the team conducts numerous commercial research projects, with a particular specialism in the visitor economy and event evaluation. Over the last 10 years, North West Research has completed over 250 projects for both public and private sector clients. 2 | Southport Destination Survey 2014 NORTH WEST RESEARCH CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1.2 Research aims 1 1.3 Methodology VISITOR PROFILE 2.1 Visitor origin 2.2 Group composition 2.3 Employment status 2 VISIT PROFILE 3.1 Type of visit 3.2 Accommodation 3 VISIT MOTIVATION 4.1 Visit motivation 4.2 Marketing influences 4.3 Frequency of visits to Southport 4 TRANSPORT 5.1 Mode of transport 5.2 Car park usage 5 VISIT SATISFACTION 6.1 Visit satisfaction ratings 6.2 Safety 6.3 Likelihood of recommending 6 6.4 Overall satisfaction TOURISM INFORMATION CENTRES 7.1 TIC Awareness 7 VISIT ACTIVITY 8.1 Visit activity 8.2 Future visits to Sefton‟s Natural Coast 8 VISITOR SPEND 9.1 Visitors staying in Southport 9.2 Visitors staying outside Southport 9.3 Day visitors 9 APPENDIX 1: Questionnaire 3 | Southport Destination Survey 2014 NORTH WEST RESEARCH INTRODUCTION 1 1.1: BACKGROUND The Southport Destination Survey is a study focusing on exploring visitor patterns, establishing what motivates people to visit the town, identifying visitor spending patterns, and examining visitor perceptions and satisfaction ratings. -

Ryde Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Directorate of Economy and Environment Director Stuart Love Ryde Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal Adopted April 2011 [Insert images here] Conservation and Design Planning Services 01983 823552 [email protected] Contents Conservation Area Boundary Map Introduction 1 RYDE CONSERVATION AREA Location, context and setting 1 Historic development of Ryde 2 Archaeological potential 6 SPATIAL ANALYSIS Character areas 6 Key views and vistas 6 Character area and key views map 7 Aerial photograph 8 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 1. Esplanade, Pier and Seafront 9 2. Historic Core and Commercial Centre 15 3. Regency and Victorian Housing 24 4. Pelhamfield, Ryde School and All Saints Church 31 5. Ryde Cemetery 36 CONDITION ANALYSIS Problems, pressures and the capacity for change 41 Potential for enhancements 40 General guidance 43 Bibliography and references 46 Appendix A– Boundary description 47 Ryde Conservation Area Appraisal 1 1 Introduction extended in December 1999. The Ryde Conservation Area adjoins the St John’s, Ryde 1.1 The Isle of Wight Council recognises Conservation Area, designated in December that a quality built environment is an essential 1988. element in creating distinctive, enjoyable and successful places in which to live and work. 2.2 This appraisal has been produced Our EcoIsland Sustainable Community using information contained within Historic Strategy and Island Plan Core Strategy Environment Records (HER), the Historic recognise that our historic environment assets Landscape Characterisation (HLC), the attract investment and tourism, can provide a Historic Environment Action Plan (HEAP), and focus for successful regeneration and are the Isle of Wight Records Office. It also refers highly valued by local communities. -

Rails by the Sea.Pdf

1 RAILS BY THE SEA 2 RAILS BY THE SEA In what ways was the development of the seaside miniature railway influenced by the seaside spectacle and individual endeavour from 1900 until the present day? Dr. Marcus George Rooks, BDS (U. Wales). Primary FDSRCS(Eng) MA By Research and Independent Study. University of York Department of History September 2012 3 Abstract Little academic research has been undertaken concerning Seaside Miniature Railways as they fall outside more traditional subjects such as standard gauge and narrow gauge railway history and development. This dissertation is the first academic study on the subject and draws together aspects of miniature railways, fairground and leisure culture. It examines their history from their inception within the newly developing fairground culture of the United States towards the end of the 19th. century and their subsequent establishment and development within the UK. The development of the seaside and fairground spectacular were the catalysts for the establishment of the SMR in the UK. Their development was largely due to two individuals, W. Bassett-Lowke and Henry Greenly who realized their potential and the need to ally them with a suitable site such as the seaside resort. Without their input there is no doubt that SMRs would not have developed as they did. When they withdrew from the culture subsequent development was firmly in the hands of a number of individual entrepreneurs. Although embedded in the fairground culture they were not totally reliant on it which allowed them to flourish within the seaside resort even though the traditional fairground was in decline. -

Simon Robertshas Photographed Every British Pleasure Pier There Is

Simon Roberts has photographed every British pleasure pier there is – and several that there aren’t. Overleaf, Francis Hodgson celebrates this devotion to imperilled treasures 14 15 here are 58 surviving pleasure piers in Britain and Simon Roberts has photographed them all. He has also photographed some of the vanished ones, as you can see from his picture of Shanklin Pier on the Isle of Wight (on page 21), destroyed in the great storm which did so much damage in southern England on October 16, 1987. Roberts is a human geographer by training, and his study of piers is a natural development of his previous major work, We English, which looked at the changing patterns of leisure in a country in which a rising population and decreasing mass employment mean that more of us have more time upon our hands than ever before. We tend to forget that holidays are a relatively new phenomenon, but it was only after the Bank Holiday Act of 1871 that paid leave gradually became the norm, and cheap, easily reachable leisure resorts a necessity. Resorts were commercial propositions, and the pier was often a major investment to draw crowds. Consortia of local businessmen would get together to provide the finance and appoint agents to get the thing Previous page done: a complex chicane of lobbying for private spans English Channel legislation, engineering, and marketing. Around design Eugenius Birch construction Raked the same time, a number of Acts made it possible and vertical cast iron screw to limit liability for shareholders in speculative piles supporting lattice companies. -

Pier Pressure: Best Practice in the Rehabilitation of British Seaside Piers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Pier pressure: Best practice in the rehabilitation of British seaside piers A. Chapman Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK ABSTRACT: Victorian seaside piers are icons of British national identity and a fundamental component of seaside resorts. Nevertheless, these important markers of British heritage are under threat: in the early 20th century nearly 100 piers graced the UK coastline, but almost half have now gone. Piers face an uncertain future: 20% of piers are currently deemed ‘at risk’. Seaside piers are vital to coastal communities in terms of resort identity, heritage, employment, community pride, and tourism. Research into the sustainability of these iconic structures is a matter of urgency. This paper examines best practice in pier regeneration projects that are successful and self-sustaining. The paper draws on four case studies of British seaside piers that have recently undergone, or are currently being, regenerated: Weston Super-Mare Grand pier; Hastings pier; Southport pier; and Penarth pier. This study identifies critical success factors in pier regeneration and examines the socio-economic sustainability of seaside piers. 1 INTRODUCTION This paper focuses on British seaside piers. Seaside pleasure piers are an uniquely British phenomena, being developed from the early 19th century onwards as landing jetties for the holidaymakers arriving at the resorts via paddle steamers. As seaside resorts developed, so too did their piers, transforming by the late 19th century into places for middle-class tourists to promenade, and by the 20th century as hubs of popular entertainment: the pleasure pier. -

Dear Swimmer April 2-16 P2P Swim 2016 I Am Pleased to Announce That

12 The Glade Wroxall Ventnor I.O.W. PO38 3QA Tel : 01983 852625 Affiliated to ASA Southern Region & BLDSA E-mail : [email protected] Dear Swimmer April 2-16 P2P Swim 2016 I am pleased to announce that the swim this year will be held on August 6th. The swim start will be later than usual due to the tides being more tricky this year. The swim will start at 2:30pm from the Sandown Lifeboat station. It has been decided to keep the entries as in previous year (i.e. no wet suits). It is one of the few swims that doesn’t have this category and the overwhelming majority of swimmer feedback last year was to keep it as it always has been for the last 60 odd years. The Pier to Pier swim follows a long tradition here on the IOW. When it first started 64 years ago the Deep Sea Fishermen and other locals threw down the gauntlet during Shanklin Regatta week and challenged each other to a race in the sea from one end of the bay to the other, notably from Sandown Pier to Shanklin Pier! They swam in the traditional swim gear of the day in the open sea whatever the conditions! No risk assessment, no safety cover probably, few officials, no numbered hats e.t.c. Over 40 of last year’s swimmers expressed support for ‘skins’ and suits of course! Remember you are entering a long standing traditional swim following in the footsteps of the deep sea fishermen of yester year! We now run into the sea rather than jump off the pier, we are accompanied (for safety reasons) by so many kayakers, fishermen, Sandown Lifeboat and Ryde Inshore Rescue! We finish the race on the beach by Shanklin Rowing Club. -

BRSUG Number Mineral Name Hey Index Group Hey No

BRSUG Number Mineral name Hey Index Group Hey No. Chem. Country Locality Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-37 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Basset Mines, nr. Redruth, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-151 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Phoenix mine, Cheese Wring, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-280 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 County Bridge Quarry, Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and South Caradon Mine, 4 miles N of Liskeard, B-319 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-394 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 ? Cornwall? Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-395 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] U.K., 17 Cornwall Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-539 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Houghton, Michigan Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-540 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, Ag and B-541 Copper Au) 1.1 4[Cu] North America, U.S.A Keweenaw Peninsula, Michigan, Elements and Alloys (including the arsenides, antimonides and bismuthides of Cu, -

Quarterly Newsletter Summer 2017 Erne Bay Historical Records Society

Herne Bay Historical Records Society Founded 1932 Registered Charity No. 1148803 Custodian s of the Town’s Archive Quarterly Newsletter Summer 2017 Issue No. 6 Welcome Contents Society News HBHRS Members update 2 Heritage Centre Opening Policing in the 1920s (part 2) 3 Who are you going to call? 4 Another mystery painting 6 Herne Bay’s Hospitals 7 Trade Directories 9 Image Gallery 10 Society Contacts 11 Society Publications 11 Ev ents and dates for your diary 12 Chairman, Mike Bundock and Lord Mayor , Cllr. Rosemary Doyle speaking to the audience on 1 st July. Saturday 1 st July marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the HBHRS. After a brief speech commencing at 12 noon, Lord Mayor of Canterbury, Councilor Rosemary Doyle cut the ribbon to signify the official opening of our Heritage Centre. The event was attended by around 100 members and well -wishers, a number that exceeded all expectations. We enjoyed a steady stream of visitors for the remainder of the afternoon, with many favourable comments. Lord Mayor, Cllr. Rosemary Doyle , cuts the ribbon. As previously advised, we have managed to secure a At present, we are open to the public every lease on 8 1 Central Parade, the former Clock Tower Wednesday and Saturday from 11am until 3pm. So far, Information Centre. This means that for the first time after our first month, we are pleased to be able to since 1938, we have our own front door! The opening report several hundred visitors, a number of new of the Heritage Centre was, of course, preceded by lots members to the society as well as the recruitment of a of hard work and to our dedicated team of volunteers , small team of volunteers.