Phinehas: Hero Or Vigilante?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Order and Significance of the Sealed Tribes of Revelation 7:4-8

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2011 The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8 Michael W. Troxell Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Troxell, Michael W., "The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8" (2011). Master's Theses. 56. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 by Michael W. Troxell Adviser: Ranko Stefanovic ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 Name of researcher: Michael W. Troxell Name and degree of faculty adviser: Ranko Stefanovic, Ph.D. Date completed: November 2011 Problem John’s list of twelve tribes of Israel in Rev 7, representing those who are sealed in the last days, has been the source of much debate through the years. This present study was to determine if there is any theological significance to the composition of the names in John’s list. -

The Priestly Covenant

1 THE PRIESTLY COVENANT THE SETTING OF THE PRIESTLY COVENANT Numbers begins with God commanding Moses to take a census of the people a little over a year after the Exodus The people have left Mt. Sinai and have begun their journey toward the promised land Numbers covers a period of time known as the wilderness wanderings, the time from when Israel departed Mt. Sinai to when they were about to enter the promised land (a period which lasted 38 years, 9 months and 10 days) The book is called “Numbers” because of the two censuses taken in Numbers 1 and 26 God told them how to arrange themselves as tribes around the tabernacle when camped (Num 2) The Levites were given instructions regarding their special role (Num 3, 4, 8) The people were given instructions regarding defilement and ceremonial uncleanness (Num 5) Instructions regarding the Nazirites were given (Num 6) The people complained after leaving Sinai about their lack of meat so God provided quail (Num 11) Miriam and Aaron rebelled against Moses (Num 12) The 12 spies went into the land and brought back a report which led the people to rebel (Num 13-14) Korah led a rebellion of 250 leaders against Moses (Num 16) Moses and Aaron were told they would not enter the promised land due to Moses’ disobedience (Num 20) God sent a plague amongst the camp for their complaining and then provided the bronze serpent; they defeated Sihon and Og (Num 21) Balak, king of Moab, heard of this great conquering hoard, and sought for Balaam, a seer, to bring a curse on them (Num 22-24) But Balaam blessed Israel 3 different times instead of cursed them 2 “Balaam has spoken God’s word, and God has said that the promises of heir, covenant and land will indeed be fulfilled. -

Priests and Cults in the Book of the Twelve

PRIESTS & CULTS in the BOOK OF THE TWELVE Edited by Lena-Sofia Tiemeyer Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Priests and Cults in the Book of the twelve anCient near eastern MonograPhs General Editors alan lenzi Juan Manuel tebes Editorial Board: reinhard achenbach C. l. Crouch esther J. hamori rené krüger Martti nissinen graciela gestoso singer number 14 Priests and Cults in the Book of the twelve Edited by lena-sofia tiemeyer Atlanta Copyright © 2016 by sBl Press all rights reserved. no part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright act or in writing from the publisher. requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the rights and Permissions office,s Bl Press, 825 hous- ton Mill road, atlanta, ga 30329 usa. library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data names: tiemeyer, lena-sofia, 1969- editor. | krispenz, Jutta. idolatry, apostasy, prostitution : hosea’s struggle against the cult. Container of (work): title: Priests and cults in the Book of the twelve / edited by lena-sofia tiemeyer. description: atlanta : sBl Press, [2016] | ©2016 | series: ancient near east monographs ; number 14 | includes bibliographical references and index. identifiers: lCCn 2016005375 (print) | lCCn 2016005863 (ebook) | isBn 9781628371345 (pbk. : alk. paper) | isBn 9780884141549 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isBn 9780884141532 (ebook) subjects: lCSH: Priests, Jewish. -

Ethical Implications of the Collusion of Prophets and Priests in Micah 3:5–7, 111

630 Boloje, “Trading Yahweh’s Word,” OTE 31/3 (2018): 630-650 Trading Yahweh’s Word for a Price: Ethical Implications of the Collusion of Prophets and Priests in Micah 3:5–7, 111 BLESSING ONORIODE BOLOJE (UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA) ABSTRACT Trading Yahweh’s word for a price is an attempt to articulate the implications of the mercenary attitude of prophets and priests in Micah 3:5–7, 11, in discharging their duties as religious functionaries. The article examines Micah’s indictment of charismatic and cultic Judeans’ self-centred leadership in commercialising Yahweh’s word. This exploration is done against the background of the functions and responsibility of prophets and priests in the HB/OT. Prophets and priests both functioned in the religion of Ancient Israel and Judah as channels for the transmission of Yahweh’s word to their people and nation. However, Micah presents a charismatic and cultic Judean leadership that was bereft of ethical standards of responsibility, reliability, constancy and integrity. Rather than embodying ethical character that could inspire confidence and commitment, they traded Yahweh’s word for symbols of wealth and power and thus became stumbling blocks to genuine orthodoxy. Such attempts to lower the standard of God’s demand on people so as to gratify oneself in a religious function that is designed to embody integrity, honesty, reliability and accountability constitute an affront to Yahweh. Additionally, it is an abuse of privilege and position, and amounts to religious deception and economic idolatry and creates a false sense of security. KEYWORDS: Micah, prophets and priests, inverted oracles and commercialised teachings, Yahweh’s word, wealth and power, economic idolatry. -

The Internal Consistency and Historical Reliability of the Biblical Genealogies

Vetus Testamentum XL, 2 (1990) THE INTERNAL CONSISTENCY AND HISTORICAL RELIABILITY OF THE BIBLICAL GENEALOGIES by GARY A. RENDSBURG Ithaca, New York The general trend among scholars in recent years has been to treat the genealogies recorded in the Bible with an increased skep- ticism. Whereas past generations of scholars may have been ready to affirm the trustworthiness of at least some of the Israelite lineages, current research in this area has led to the opposite con- clusion. Provided with parallels both from ancient Near Eastern documents and from the sociological and anthropological study of tribal societies of the present, most scholars today contend that the biblical genealogies do not constitute a reliable source for the reconstruction of history.' The current approach is that the genealogies may retain some value for the reconstruction of political ties on a national or tribal level,2 but that in no way should they be taken at face value. This is especially true for those genealogies which purport to be from early Israelite times, such as the lineages of Moses or David. In the present article I will offer some evidence which, depending on how it is judged, may stem the tide described above. The approach to be taken will differ from recent work on the subject, in that it will adduce no external evidence from either ancient or modern times. Instead, I will concentrate on the genealogies them- selves, in particular those lineages of characters who appear in Exodus through Joshua. I anticipate one of the results of my analysis with the following statement: the genealogies themselves 1 See especially R. -

Then Phinehas Stood up (Numbers 25:1-18)

Then Phinehas Stood Up NUMBERS 25:1-18 Baxter T. Exum (#1527) Four Lakes Church of Christ Madison, Wisconsin December 15, 2019 This past Wednesday evening, we studied Psalm 106, where the author is summarizing the history of God’s people, and in that Psalm we came to verses 28-30, where the text says that, 28 They joined themselves also to Baal-peor, And ate sacrifices offered to the dead. 29 Thus they provoked Him to anger with their deeds, And the plague Broke out among them. 30 Then Phinehas stood up and interposed, And so the plague was stayed. We just briefly mentioned how this describes Phinehas getting angry at two people apparently committing sexual sin with each other, and how Phinehas stands up, takes a spear, and simultaneously kills both the man and woman by spearing them together through the belly, most likely as they are in the act. We moved along quickly, since Psalm 106 is rather long, but right after class, one of our teens runs up to me immediately and basically says, “Wait just a minute! You need to tell me more about this spear thing!” And it is a dramatic account, so I did the best I could to just briefly summarize what happens here. As you might know, we are working through some sermon requests right now, so I thought there might a value to all of us looking at the background to this passage this morning. As I prepared for today’s lesson, I started by wondering whether I might be able to find a spear in time for today. -

The Concept of Vengeance in the Book of Revelation in Its Old Testament and Near Eastern Context

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 1986 The Concept of Vengeance in the Book of Revelation in its Old Testament and Near Eastern Context Joel Nobel Musvosvi Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Musvosvi, Joel Nobel, "The Concept of Vengeance in the Book of Revelation in its Old Testament and Near Eastern Context" (1986). Dissertations. 103. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/103 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

1 Mercy Seminar I.4 Micah 3:1 and I Said

1 Mercy Seminar I.4 Micah 3:1 And I said: Listen, you heads of Jacob and rulers of the house of Israel! Should you not know justice?— 2you who hate the good and love the evil, who tear the skin off my people, and the flesh off their bones; 3who eat the flesh of my people, flay their skin off them, break their bones in pieces, and chop them up like meat in a kettle, like flesh in a caldron. 4Then they will cry to the Lord, but he will not answer them; he will hide his face from them at that time, because they have acted wickedly. 5Thus says the Lord concerning the prophets who lead my people astray, who cry “Peace” when they have something to eat, but declare war against those who put nothing into their mouths. 6Therefore it shall be night to you, without vision, and darkness to you, without revelation. The sun shall go down upon the prophets, and the day shall be black over them; 7the seers shall be disgraced, and the diviners put to shame; they shall all cover their lips, for there is no answer from God. 8But as for me, I am filled with power, with the spirit of the Lord, and with justice and might, to declare to Jacob his transgression and to Israel his sin. 9Hear this, you rulers of the house of Jacob and chiefs of the house of Israel, who abhor justice and pervert all equity, 10who build Zion with blood and Jerusalem with wrong! 11Its rulers give judgment for a bribe, its priests teach for a price, its prophets give oracles for money; yet they lean upon the Lord and say, “Surely the Lord is with us! No harm shall come upon us.” 12Therefore because of you Zion shall be plowed as a field; Jerusalem shall become a heap of ruins, and the mountain of the house a wooded height. -

The Zeal of Phinehas: the Bible and the Legitimation of Violence

JBL 122/1 (2003) 3–21 THE ZEAL OF PHINEHAS: THE BIBLE AND THE LEGITIMATION OF VIOLENCE JOHN J. COLLINS [email protected] Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511 “The Bible, of all books, is the most dangerous one, the one that has been endowed with the power to kill,” writes Mieke Bal.1 Like many striking apho- risms, this statement is not quite true. Some other books, notably the Qur<an, are surely as lethal, and in any case, to coin a phrase, books don’t kill people. But Professor Bal has a point nonetheless. When it became clear that the ter- rorists of September 11, 2001, saw or imagined their grievances in religious terms, any reader of the Bible should have had a flash of recognition. The Mus- lim extremists drew their inspiration from the Qur<an rather than the Bible, but both Scriptures draw from the same wellsprings of ancient Near Eastern reli- gion. While it is true that both Bible and Qur<an admit of various readings and emphases, and that terrorist hermeneutics can be seen as a case of the devil cit- ing Scripture for his purpose, it is also true that the devil does not have to work very hard to find biblical precedents for the legitimation of violence. Many peo- ple in the modern world suspect that there is an intrinsic link between violence and what Jan Assmann has called “the Mosaic distinction” between true and false religion,2 or even between violence and monotheism or monolatry.3 Such claims are, no doubt, too simple. -

Zealous with the Zeal of God Introduction: the Text Accounted As Righteousness

ZEALOUS WITH THE ZEAL OF GOD INTRODUCTION: This story of Phinehas is not one that I remember growing up with. The children’s story bibles usually skip over it because it’s bloody and graphic and involves a couple flaunting their sexual immorality. In a day when the demand for tolerance is the air we breathe, the story of Phinehas needs to be burned in our minds. This is, simply put, a story of a man of God taking a stand against sin. THE TEXT: “…Now when Phinehas the son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron the priest, saw it, he rose from among the congre- gation and took a javelin in his hand; and he went after the man of Israel into the tent and thrust both of them through, the man of Israel, and the woman through her body. So the plague was stopped among the people…” (Numbers 25). ACCOUNTED AS RIGHTEOUSNESS: In Psalm 106:28-31, the psalmist summarizes the story told in Numbers 25. He says that Phinehas stood up and intervened in the sin of Zimri, stopping the plague. Then the psalmist says, “That was accounted to him for righteousness.” What exactly does the psalmist mean? This phrase, “accounted to him for righteousness”, is used three other times in the Bible. The first is in Genesis 15 when Abram believes God’s promises. The second is in Romans 4 when Paul is explaining what the faith of Abram was like. Paul makes it clear that it is Abram’s faith that was accounted to him as righteousness. -

A Pilgrimage Through the Old Testament

A PILGRIMAGE THROUGH THE OLD TESTAMENT ** Year 2 of 3 ** Cold Harbor Road Church Of Christ Mechanicsville, Virginia Old Testament Curriculum TABLE OF CONTENTS Lesson 53: OLD WINESKINS/SUN STOOD STILL Joshua 8-10 .................................................................................................... 5 Lesson 54: JOSHUA CONQUERS NORTHERN CANAAN Joshua 11-15 .................................................................................................. 10 Lesson 55: DIVIDING THE LAND Joshua 16-22 .................................................................................................. 14 Lesson 56: JOSHUA’S LAST DAYS Joshua 23,24................................................................................................... 19 Lesson 57: WHEN JUDGES RULED Judges 1-3 ...................................................................................................... 23 Lesson 58: THE NORTHERN CONFLICT Judges 4,5 ...................................................................................................... 28 Lesson 59: GIDEON – MIGHTY MAN OF VALOUR Judges 6-8 ...................................................................................................... 33 Lesson 60: ABIMELECH AND JEPHTHAH Judges 9-12 .................................................................................................... 38 Lesson 61: SAMSON: GOD’S MIGHTY MAN OF STRENGTH Judges 13-16 .................................................................................................. 44 Lesson 62: LAWLESS TIMES Judges -

Eli's Failure and Zadok's Success

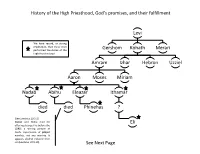

History of the High Priesthood, God’s promises, and their fulfillment Levi We have record, or strong implication, that these men performed the duties of the Gershom Kohath Merari High Priest in Israel Amram Izhar Hebron Uzziel Aaron Moses Miriam Nadab Abihu Eleazar Ithamar died died Phinehas ? (See Leviticus 10:1-2) Nadab and Abihu died for Eli offering strange fire before the LORD; a stirring picture of God’s expectation of proper worship, not any worship. It appears alcohol induced their sin (Leviticus 10:9-10) See Next Page History of the High Priesthood, God’s promises, and their fulfillment Eli was God’s High Priest at the end of Nadab Abihu Eleazar Ithamar the judges. Due to Eli and his sons’ rebellion, God promised that (1) there would never be an old man in Eli’s household and (2) The family would (See Numbers 25:11) Phinehas ? be removed from the Priesthood (1 Perpetual priesthood first Samuel 2:31-35) promised to Phinehas for his zeal against sin. Was the priest Abishua Eli when Israel entered the promised land (Joshua 22) Bukki Hophni Phinehas 1 Samuel 14:3 records the lineage of Phinehas Uzzi Ichabod Ahitub Killed by Doeg the Edomite at the We have record, or strong command of Saul, because he implication, that these men Zerahaiah Ahiah helped David flee (1 Samuel 21-22) performed the duties of the High Priest in Israel Meraioth ? (See 1 Samuel 22:20; 1 Kings 1:7; 2:26-27) High Priest during the reign of David with Zadok. Fled to David after the death of his Amariah Ahimelech father Ahimelech.