Biblical Pragmatism in the Pandemic Outbreak of Numbers 25:1–18: Towards an African Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Expositor

THE EXPOSITOR. BALAAM: AN EXPOSITION AND STUDY. III. The Conclusion. WE have now studied all the Scriptures which relate to Balaam, and if our study has added but few new features to his character, it has served, I hope, to bring out his features more clearly, to cast higher lights and deeper shadows upon them, and to define and enlarge our conceptions both of the good and of the evil qualities of the man. The problem of his character-how a good man could be so. bad and a great man so base-has not yet been solved ; we are as far per haps from its solution as ever : but something-much has been gained if only we have the terms of that problem more distinctly and fully before our minds. To reach the solution of it, in so far as we can reach it, we must fall back on the second method of inquiry which, at the outset, I proposed to employ. We must apply the comparative method to the history and character of Balaam ; we must place him beside other prophets as faulty and sinful as himself, and in whom the elements were as strangely mixed as they were in him : we must endeavour to classify him, and to read the problem of his life in the light of that of men of his own order and type. Yet that is by no means easy to do without putting him to a grave disadvantage. For the only prophets with whom We can compare him are the Hebrew prophets ; and ·Balaam JULY, 1883. -

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik

Prophets, Posters and Poetry Joshua Fallik Subject Area: Torah (Prophets) Multi-unit lesson plan Target age: 5th – 8th grades, 9th – 12th grades Objectives: • To acquaint students with prophets they may be unfamiliar with. • To familiarize the students with the social and moral message of selected prophets by engaging their analytical minds and visual senses. • To have students reflect in various media on the message of each of these prophets. • To introduce the students to contemporary examples of individuals who seem to live in the spirit of the prophets and their teachings. Materials: Descriptions of various forms of poetry including haiku, cinquain, acrostic, and free verse. Poster board, paper, markers, crayons, pencils, erasers. Quotations from the specific prophet being studied. Students may choose to use any of the materials available to create their sketches and posters. Class 1 through 3: Introduction to the prophets. The prophet Jonah. Teacher briefly talks about the role of the prophets. (See What is a Prophet, below) Teacher asks the students to relate the story of Jonah. Teacher briefly discusses the historical and social background of the prophet. Teacher asks if they can think of any fictional characters named Jonah. Why is the son in Sleepless in Seattle named Jonah? Teacher briefly talks about different forms of poetry. (see Poetry Forms, below) Students are asked to write a poem (any format) about the prophet Jonah. Students then draw a sketch that illustrates the Jonah story. Students create a poster based on the sketch and incorporating the poem they have written. Classes 4 through 8: The prophet Micah. -

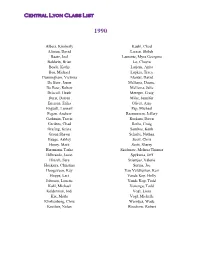

Central Lyon Class List

Central Lyon Class List 1990 Albers, Kimberly Kuehl, Chad Altman, David Larsen, Shiloh Baatz, Joel Laurente, Myra Georgina Baldwin, Brian Lo, Chayra Boyle, Kathy Lutjens, Anita Bus, Michael Lupkes, Tracy Cunningham, Victoria Mantal, David De Beor, Jason Mellema, Duane, De Boer, Robert Mellema, Julie Driscoll, Heath Metzger, Craig Durst, Darren Milar, Jennifer Enersen, Erika Oliver, Amy Enguall, Lennart Pap, Michael Fegan, Andrew Rasmussem, Jeffery Gathman, Travis Roskam, Dawn Gerdees, Chad Roths, Craig Grafing, Krista Sambos, Keith Groen Shawn Schulte, Nathan Hauge, Ashley Scott, Chris Henry, Mark Scott, Sherry Herrmann, Tasha Skidmore, Melissa Thinner Hilbrands, Jason Spyksma, Jeff Hinsch, Sara Stientjes, Valerie Hoekstra, Christina Surma, Joe Hoogeveen, Kay Van Veldhuizen, Keri Hoppe, Lari Vande Kop, Holly Johnson, Lonette Vande Kop, Todd Kahl, Michael Venenga, Todd Kelderman, Jodi Vogl, Lissa Kix, Marla Vogl, Michelle Klinkenborg, Chris Warntjes, Wade Kooiker, Nolan Woodrow, Robert Central Lyon Class List 1991 Andy, Anderson Mantle, Mark Lewis, Anderson Matson, Sherry Rachel, Baatz McDonald, Chad Lyle, Bauer Miller, Bobby Darcy, Berg Miller, Penny Paul, Berg Moser, Jason Shane, Boeve Mowry, Lisa Borman, Zachary Mulder, Daniel Breuker, Theodore Olsen, Lisa Christians, Amy Popkes, Wade De Yong, Jana Rath, Todd Delfs, Rodney Rau, Gary Ellsworth, Jason Roths, June Fegan, Carrie Schillings, Roth Gardner, Sara Schubert, Traci Gingras, Cindy Scott, Chuck Goette, Holly Solheim, Bill Grafing, Jennifer Steenblock, Amy Grafing, Robin Stettnichs, -

Zealots – Fanatics Or Heroes Parshat Pinchas

Zealots – Fanatics or Heroes Parshat Pinchas - 2005 We are a people who love labels of the extremes. In assessing zealots there is a very, very thin line in determining who is a hero, worthy of praise and adoration and who is a fanatic deserving of contempt and rejection. Over the centuries we have been blessed by many zealots who sought to keep the Jewish spark alive. One collectively accepted hero is Mattiahu, whose blow against a Jew worshipping a pagan god, cascaded into the Maccabean revolt and our eventual freedom from Assyrian tyranny. On the other hand, during the last decade we have witnessed a number of zealots who chose to take the law into their own hands. These include: Dr. Baruch Goldstein of the Hebron massacre; Yigal Amir, Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin’s assassin, and Eden Natan Zada, a young soldier who murdered four innocent Israeli Arabs. Yet, one person’s fanatic is another’s hero. Being a zealot does not mean automatic inclusion into the Hall of Jewish heroes. Dramatic action driven by religious passion does not mean that Klal Yisrael – the nation of Israel – has benefited -- has been lifted to a higher spiritual plane. In fact, it may be just the opposite. Passion supporting a point-of-view, whether it is for withdrawal from the territories or against withdrawal, does not permit one Jew to act against another Jew or gentile with violence. So, what about our ancestors? Didn’t they face the thorny issue of zealotry – fanatics or heroes? How did they respond to such actions? Torah is not only a book of our past…it is the story of our people l’Dor v’Dor – from generation to generation. -

The Order and Significance of the Sealed Tribes of Revelation 7:4-8

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2011 The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8 Michael W. Troxell Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Troxell, Michael W., "The Order and Significance of the Sealed ribesT of Revelation 7:4-8" (2011). Master's Theses. 56. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 by Michael W. Troxell Adviser: Ranko Stefanovic ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORDER AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SEALED TRIBES OF REVELATION 7:4-8 Name of researcher: Michael W. Troxell Name and degree of faculty adviser: Ranko Stefanovic, Ph.D. Date completed: November 2011 Problem John’s list of twelve tribes of Israel in Rev 7, representing those who are sealed in the last days, has been the source of much debate through the years. This present study was to determine if there is any theological significance to the composition of the names in John’s list. -

Candc-Family

סב ׳ ׳ ד סחנפ שת ״ ף Pinchas 5780 Moral vs. political Decisions ** KEY IDEA OF THE WEEK ** For a nation to flourish, politics must be moral PARSHAT PINCHAS IN A NUTSHELL Despite escaping Bilam’s curses, the Israelites bring disaster inherit his portion. God tells Moses that they are indeed able on themselves anyway when Moabite women convince to inherit their father’s portion of the land. The second story some Israelite men to have forbidden relations with them is about Moses’ request that God appoint someone to be the and to worship idols. 24,000 people suffer a deadly plague as new leader of the people after he dies. The parsha ends with punishment, until Pinchas, in an act of zeal, rises up against two chapters about the different sacrifices that should be the wrongdoers to slay an Israelite man and Moabite woman brought daily, weekly, monthly, and on festivals. who are sinning together publicly. Immediately, the plague ends. God gives Pinchas a “covenant of peace” and “lasting Priesthood” as a reward for this act of leadership. The parsha then tells two stories. The first is about the QUESTION TO PONDER: daughters of Tzelofechad who ask Moses for their own share in the land of Israel because their father had no sons to Was Pinchas right or wrong to slay the man and woman? THE CORE IDEA The Israelites began mixing with Midianite women and were God declared Pinchas a hero. He had saved the Israelites soon worshipping their gods. A plague raged and 24,000 from destruction by showing a passion for God that was the Jewish men died. -

Recasting Moses

4. The memory of Moses in Paul’s autobiographical references: The figures of Moses in the letters of Paul 4.1. Introduction In recent years, a significant scholarly debate has taken place concerning Paul’s use of the figure of Moses. Whereas some scholars such as Peter Jones and Carol Stockhausen have claimed that Paul sees himself specifically as a “second Moses”,247 others such as Peter Oakes have asserted that Moses does not play any major role in Paul’s letter, “Moses, as a figure, is not as important as we might expect, despite being intimately identified with the law”.248 The discussion has primarily taken place in relation to only one of Paul’s letters, namely 2 Corinthians. In this chapter, I seek to contribute to the debate by examining Paul’s use of the figure of Moses in all his undisputed letters. On the face of it, the figure of Moses seems to turn up at rare intervals only in Paul’s letters. Paul just refers to Moses explicitly nine times in his letters, five times in the Corinthian correspondence and four in the letter to the Romans.249 In addition, he merely seems to allude to Moses only a few times.250 In contrast to Philo and Josephus, Paul nowhere presents a com- prehensive view of Moses. His use of Moses is provisional and sometimes even contradictory. Because of the multiplicity of meanings, I shall there- fore speak of the figures of Moses in the letters of Paul rather than a single figure. Actually, his use of Moses even seems to change within the Corinthian correspondence. -

Deuteronomy 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Deuteronomy 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title of this book in the Hebrew Bible was its first two words, 'elleh haddebarim, which translate into English as "these are the words" (1:1). Ancient Near Eastern suzerainty treaties began the same way.1 So the Jewish title gives a strong clue to the literary character of Deuteronomy. The English title comes from a Latinized form of the Septuagint (Greek) translation title. "Deuteronomy" means "second law" in Greek. We might suppose that this title arose from the idea that Deuteronomy records the law as Moses repeated it to the new generation of Israelites who were preparing to enter the land, but this is not the case. It came from a mistranslation of a phrase in 17:18. In that passage, God commanded Israel's kings to prepare "a copy of this law" for themselves. The Septuagint translators mistakenly rendered this phrase "this second [repeated] law." The Vulgate (Latin) translation, influenced by the Septuagint, translated the phrase "second law" as deuteronomium, from which "Deuteronomy" is a transliteration. The Book of Deuteronomy is, to some extent, however, a repetition to the new generation of the Law that God gave at Mt. Sinai. For example, about 50 percent of the "Book of the Covenant" (Exod. 20:23— 23:33) is paralleled in Deuteronomy.2 Thus God overruled the translators' error, and gave us a title for the book in English that is appropriate, in view of the contents of the book.3 1Meredith G. Kline, "Deuteronomy," in The Wycliffe Bible Commentary, p. -

The Priestly Covenant

1 THE PRIESTLY COVENANT THE SETTING OF THE PRIESTLY COVENANT Numbers begins with God commanding Moses to take a census of the people a little over a year after the Exodus The people have left Mt. Sinai and have begun their journey toward the promised land Numbers covers a period of time known as the wilderness wanderings, the time from when Israel departed Mt. Sinai to when they were about to enter the promised land (a period which lasted 38 years, 9 months and 10 days) The book is called “Numbers” because of the two censuses taken in Numbers 1 and 26 God told them how to arrange themselves as tribes around the tabernacle when camped (Num 2) The Levites were given instructions regarding their special role (Num 3, 4, 8) The people were given instructions regarding defilement and ceremonial uncleanness (Num 5) Instructions regarding the Nazirites were given (Num 6) The people complained after leaving Sinai about their lack of meat so God provided quail (Num 11) Miriam and Aaron rebelled against Moses (Num 12) The 12 spies went into the land and brought back a report which led the people to rebel (Num 13-14) Korah led a rebellion of 250 leaders against Moses (Num 16) Moses and Aaron were told they would not enter the promised land due to Moses’ disobedience (Num 20) God sent a plague amongst the camp for their complaining and then provided the bronze serpent; they defeated Sihon and Og (Num 21) Balak, king of Moab, heard of this great conquering hoard, and sought for Balaam, a seer, to bring a curse on them (Num 22-24) But Balaam blessed Israel 3 different times instead of cursed them 2 “Balaam has spoken God’s word, and God has said that the promises of heir, covenant and land will indeed be fulfilled. -

A Star Was Born... About the Bifocal Reception History of Balaam

Scriptura 116 (2017:2): pp. 1-14 http://scriptura.journals.ac.za http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/116-2-1311 A STAR WAS BORN... ABOUT THE BIFOCAL RECEPTION HISTORY OF BALAAM Hans Ausloos University of the Free State Université catholique de Louvain – F.R.S.-FNRS Abstract Balaam counts among the most enigmatic characters within the Old Testament. Not everyone has the privilege of meeting an angel, and being addressed by a donkey. Moreover, the Biblical Balaam, as he is presented in Num. 22-24, has given rise to multiple interpretations: did the biblical authors want to narrate about a pagan diviner, who intended to curse the Israelites, but who was manipulated – against his will – by God in order to bless them, or was he rather considered to be a real prophet like Elijah or Isaiah? Anyway, that is at least the way he has been perceived by a segment of Christianity, considering him as one of the prophets who announced Jesus as the Christ? In the first section of this contribution, which I warmheartedly dedicate to Professor Hendrik ‘Bossie’ Bosman – we first met precisely twenty years ago during a research stay at Stellenbosch University in August 1997 – I will present the ambiguous presentation of Balaam that is given in Numbers 22-24 concisely. Secondly, I will concentrate on Balaam’s presentation in the other books of the Bible. Being aware of the fact that the reception history of the Pentateuch is one of Bossie’s fields of interest, in the last section I will show how the bifocal Biblical presentation of Balaam has left its traces on the reception of this personage in Christian arts. -

In the Face of Violence, a Covenant of Peace

פינחס תשפ"א Pinehas 5781 In the Face of Violence, a Covenant of Peace Marc Gary, Executive Vice Chancellor Emeritus, JTS Karen Armstrong, the scholar of religion and popular author act itself (the spear ended in the woman’s kubah, which may of such works as The History of God, relates that wherever refer either to her belly or her sexual part). That parashah she travels, she is often confronted by someone—a taxi ended with a plague being lifted, but no definitive word driver, an Oxford academic, an American psychiatrist—who about how God or Moses viewed this act of vigilantism confidently expresses the view that “religion has caused more (Num. 25:6–9). violence and wars than anything else.” This is quite a remarkable statement given that in the last century alone, That judgment is rendered at the beginning of this week’s tens of millions of people have been killed in two world wars, parashah and to our modern sensibilities as well as our the communist purges in the Soviet Union and its satellites, fundamental understanding of religious values, it is a stunner: and the Cambodian killing fields of the Khmer Rouge, none The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: “Pinehas, son of of which were caused by religious motivations. Elazar son of Aaron the priest, has turned back My This is not to say, of course, that religion has failed to play a wrath from the Israelites by displaying among them significant role throughout history in the instigation of wars or his passion for Me, so that I did not wipe out the the perpetration of individual acts of violence. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

STUDY GUIDE The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Balak NUMBERS 22:2-25:9 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Parashat Balak Study Guide Themes Theme 1: The Seer Balaam—Have Vision Will Travel Theme 2: It’s a Slippery Slope—the Dangers of Foreign Women INTRODUCTION n Parashat Balak the Israelites are camped on the plains of Moab, ready Ito enter Canaan. In the midst of their final preparations to enter the land God promised to their ancestors, yet another obstacle emerges. Balak, king of Moab, grows concerned about the fierce reputation of the Israelites, which he observed in the Israelites’ encounter with the Amorites (Numbers 21:21–32). Balak’s subjects worry that the Israelites, due to their large numbers, will devour the resources of Moab. In response, Balak hires a well-known seer named Balaam to curse the Israelites, thus reflecting the widely held belief in the ancient world that putting a curse on someone was an effective means of subduing an enemy. The standoff between the powers of the God of Israel and those of a foreign seer proves to be no contest. Even Balaam’s talking female donkey, who represents the biblical ideal of wisdom, recognizes the efficacy of God’s power—unlike her human master, the professional seer. Although hired to curse the Israelites, Balaam ends up blessing them instead. In a series of four oracles, Balaam ultimately does the opposite of what Balak desires and establishes that the power of Israel’s God is greater than even the most skilled human seers.