Worms Topics in Biodiversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Acanthocephala (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Coreidae) of America North of Mexico with a Key to Species

Zootaxa 2835: 30–40 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Review of Acanthocephala (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Coreidae) of America north of Mexico with a key to species J. E. McPHERSON1, RICHARD J. PACKAUSKAS2, ROBERT W. SITES3, STEVEN J. TAYLOR4, C. SCOTT BUNDY5, JEFFREY D. BRADSHAW6 & PAULA LEVIN MITCHELL7 1Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, Fort Hays State University, Hays, Kansas 67601, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3Enns Entomology Museum, Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 61820, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 5Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology, & Weed Science, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 6Department of Entomology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Panhandle Research & Extension Center, Scottsbluff, Nebraska 69361, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 7Department of Biology, Winthrop University, Rock Hill, South Carolina 29733, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A review of Acanthocephala of America north of Mexico is presented with an updated key to species. A. confraterna is considered a junior synonym of A. terminalis, thus reducing the number of known species in this region from five to four. New state and country records are presented. Key words: Coreidae, Coreinae, Acanthocephalini, Acanthocephala, North America, review, synonymy, key, distribution Introduction The genus Acanthocephala Laporte currently is represented in America north of Mexico by five species: Acan- thocephala (Acanthocephala) declivis (Say), A. -

Platyhelminthes, Nemertea, and "Aschelminthes" - A

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. III - Platyhelminthes, Nemertea, and "Aschelminthes" - A. Schmidt-Rhaesa PLATYHELMINTHES, NEMERTEA, AND “ASCHELMINTHES” A. Schmidt-Rhaesa University of Bielefeld, Germany Keywords: Platyhelminthes, Nemertea, Gnathifera, Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, Rotifera, Acanthocephala, Cycliophora, Nemathelminthes, Gastrotricha, Nematoda, Nematomorpha, Priapulida, Kinorhyncha, Loricifera Contents 1. Introduction 2. General Morphology 3. Platyhelminthes, the Flatworms 4. Nemertea (Nemertini), the Ribbon Worms 5. “Aschelminthes” 5.1. Gnathifera 5.1.1. Gnathostomulida 5.1.2. Micrognathozoa (Limnognathia maerski) 5.1.3. Rotifera 5.1.4. Acanthocephala 5.1.5. Cycliophora (Symbion pandora) 5.2. Nemathelminthes 5.2.1. Gastrotricha 5.2.2. Nematoda, the Roundworms 5.2.3. Nematomorpha, the Horsehair Worms 5.2.4. Priapulida 5.2.5. Kinorhyncha 5.2.6. Loricifera Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS This chapter provides information on several basal bilaterian groups: flatworms, nemerteans, Gnathifera,SAMPLE and Nemathelminthes. CHAPTERS These include species-rich taxa such as Nematoda and Platyhelminthes, and as taxa with few or even only one species, such as Micrognathozoa (Limnognathia maerski) and Cycliophora (Symbion pandora). All Acanthocephala and subgroups of Platyhelminthes and Nematoda, are parasites that often exhibit complex life cycles. Most of the taxa described are marine, but some have also invaded freshwater or the terrestrial environment. “Aschelminthes” are not a natural group, instead, two taxa have been recognized that were earlier summarized under this name. Gnathifera include taxa with a conspicuous jaw apparatus such as Gnathostomulida, Micrognathozoa, and Rotifera. Although they do not possess a jaw apparatus, Acanthocephala also belong to Gnathifera due to their epidermal structure. ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. -

A Multigene Phylogenetic Analysis of Terebelliform Annelids

Zhong et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011, 11:369 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/369 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Detecting the symplesiomorphy trap: a multigene phylogenetic analysis of terebelliform annelids Min Zhong1, Benjamin Hansen2, Maximilian Nesnidal2, Anja Golombek2, Kenneth M Halanych1 and Torsten H Struck2* Abstract Background: For phylogenetic reconstructions, conflict in signal is a potential problem for tree reconstruction. For instance, molecular data from different cellular components, such as the mitochondrion and nucleus, may be inconsistent with each other. Mammalian studies provide one such case of conflict where mitochondrial data, which display compositional biases, support the Marsupionta hypothesis, but nuclear data confirm the Theria hypothesis. Most observations of compositional biases in tree reconstruction have focused on lineages with different composition than the majority of the lineages under analysis. However in some situations, the position of taxa that lack compositional bias may be influenced rather than the position of taxa that possess compositional bias. This situation is due to apparent symplesiomorphic characters and known as “the symplesiomorphy trap”. Results: Herein, we report an example of the sympleisomorphy trap and how to detect it. Worms within Terebelliformia (sensu Rouse & Pleijel 2001) are mainly tube-dwelling annelids comprising five ‘families’: Alvinellidae, Ampharetidae, Terebellidae, Trichobranchidae and Pectinariidae. Using mitochondrial genomic data, as well as data from the nuclear 18S, 28S rDNA and elongation factor-1a genes, we revealed incongruence between mitochondrial and nuclear data regarding the placement of Trichobranchidae. Mitochondrial data favored a sister relationship between Terebellidae and Trichobranchidae, but nuclear data placed Trichobranchidae as sister to an Ampharetidae/Alvinellidae clade. -

(Platyhelminthes, Polycladida, Cotylea) from the Persian Gulf, Iran

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 31: 39–51 (2009)First record of the family Pseudocerotidae the Persian Gulf, Iran 39 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.31.136 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research First record of the family Pseudocerotidae (Platyhelminthes, Polycladida, Cotylea) from the Persian Gulf, Iran Zahra Khalili1, Hassan Rahimian2, Jamile Pazooki1 1 University of Shahid Beheshti, G.C, Tehran, Iran 2 University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran Corresponding authors: Hassan Rahimian ([email protected]), Zahra Khalili ([email protected]) Academic editor: E. Neubert, Z. Amr | Received 7 March 2009 | Accepted 14 August 2009 | Published 28 December 2009 Citation: Khalili Z, Rahimian H, Pazooki J (2009) First record of the family Pseudocerotidae (Platyhelminthes, Po- lycladida, Cotylea) from the Persian Gulf, Iran. In: Neubert, E, Amr, Z, Taiti, S, Gümüs, B (Eds) Animal Biodiversity in the Middle East. Proceedings of the First Middle Eastern Biodiversity Congress, Aqaba, Jordan, 20–23 October 2008. ZooKeys 31: 39–51. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.31.136 Abstract In this paper, two species of cotylean Platyhelminthes are recorded for the fi rst time from Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf, Iran. Pictures are taken from living specimens to illustrate shape and colour, and stained sec- tions and drawings are used to describe shape and organisation of some organs. Morphological characters of Persian Gulf specimens of Tytthosoceros lizardensis Newman and Cannon 1996 are compared to those of the type specimens of this species. Keywords Platyhelminthes, new records, Qeshm Island, Persian Gulf, Iran Introduction Most polyclad fl atworms inhabit coral reefs in tropical and subtropical waters, and are espe- cially species-rich throughout the Indo-Pacifi c. -

Zootaxa,Crustacean Classification

Zootaxa 1668: 313–325 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Crustacean classification: on-going controversies and unresolved problems* GEOFF A. BOXSHALL Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] *In: Zhang, Z.-Q. & Shear, W.A. (Eds) (2007) Linnaeus Tercentenary: Progress in Invertebrate Taxonomy. Zootaxa, 1668, 1–766. Table of contents Abstract . 313 Introduction . 313 Treatment of parasitic Crustacea . 315 Affinities of the Remipedia . 316 Validity of the Entomostraca . 318 Exopodites and epipodites . 319 Using of larval characters in estimating phylogenetic relationships . 320 Fossils and the crustacean stem lineage . 321 Acknowledgements . 322 References . 322 Abstract The journey from Linnaeus’s original treatment to modern crustacean systematics is briefly characterised. Progress in our understanding of phylogenetic relationships within the Crustacea is linked to continuing discoveries of new taxa, to advances in theory and to improvements in methodology. Six themes are discussed that serve to illustrate some of the major on-going controversies and unresolved problems in the field as well as to illustrate changes that have taken place since the time of Linnaeus. These themes are: 1. the treatment of parasitic Crustacea, 2. the affinities of the Remipedia, 3. the validity of the Entomostraca, 4. exopodites and epipodites, 5. using larval characters in estimating phylogenetic rela- tionships, and 6. fossils and the crustacean stem-lineage. It is concluded that the development of the stem lineage concept for the Crustacea has been dominated by consideration of taxa known only from larval or immature stages. -

Cannabis Dictionary

A MEDICAL DICTIONARY, BIBLIOGRAPHY, AND ANNOTATED RESEARCH GUIDE TO INTERNET REFERENCES JAMES N. PARKER, M.D. AND PHILIP M. PARKER, PH.D., EDITORS ii ICON Health Publications ICON Group International, Inc. 4370 La Jolla Village Drive, 4th Floor San Diego, CA 92122 USA Copyright 2003 by ICON Group International, Inc. Copyright 2003 by ICON Group International, Inc. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Last digit indicates print number: 10 9 8 7 6 4 5 3 2 1 Publisher, Health Care: Philip Parker, Ph.D. Editor(s): James Parker, M.D., Philip Parker, Ph.D. Publisher's note: The ideas, procedures, and suggestions contained in this book are not intended for the diagnosis or treatment of a health problem. As new medical or scientific information becomes available from academic and clinical research, recommended treatments and drug therapies may undergo changes. The authors, editors, and publisher have attempted to make the information in this book up to date and accurate in accord with accepted standards at the time of publication. The authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for consequences from application of the book, and make no warranty, expressed or implied, in regard to the contents of this book. Any practice described in this book should be applied by the reader in accordance with professional standards of care used in regard to the unique circumstances that may apply in each situation. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

Ctenophore Relationships and Their Placement As the Sister Group to All Other Animals

ARTICLES DOI: 10.1038/s41559-017-0331-3 Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals Nathan V. Whelan 1,2*, Kevin M. Kocot3, Tatiana P. Moroz4, Krishanu Mukherjee4, Peter Williams4, Gustav Paulay5, Leonid L. Moroz 4,6* and Kenneth M. Halanych 1* Ctenophora, comprising approximately 200 described species, is an important lineage for understanding metazoan evolution and is of great ecological and economic importance. Ctenophore diversity includes species with unique colloblasts used for prey capture, smooth and striated muscles, benthic and pelagic lifestyles, and locomotion with ciliated paddles or muscular propul- sion. However, the ancestral states of traits are debated and relationships among many lineages are unresolved. Here, using 27 newly sequenced ctenophore transcriptomes, publicly available data and methods to control systematic error, we establish the placement of Ctenophora as the sister group to all other animals and refine the phylogenetic relationships within ctenophores. Molecular clock analyses suggest modern ctenophore diversity originated approximately 350 million years ago ± 88 million years, conflicting with previous hypotheses, which suggest it originated approximately 65 million years ago. We recover Euplokamis dunlapae—a species with striated muscles—as the sister lineage to other sampled ctenophores. Ancestral state reconstruction shows that the most recent common ancestor of extant ctenophores was pelagic, possessed tentacles, was bio- luminescent and did not have separate sexes. Our results imply at least two transitions from a pelagic to benthic lifestyle within Ctenophora, suggesting that such transitions were more common in animal diversification than previously thought. tenophores, or comb jellies, have successfully colonized from species across most of the known phylogenetic diversity of nearly every marine environment and can be key species in Ctenophora. -

Solitary Entoprocts Living on Bryozoans - Commensals, Mutualists Or Parasites?

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 440 (2013) 15–21 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe Solitary entoprocts living on bryozoans - Commensals, mutualists or parasites? Yuta Tamberg ⁎, Natalia Shunatova, Eugeniy Yakovis Department of Invertebrate Zoology, St. Petersburg State University, Universitetskaja nab. 7/9, St. Petersburg, 199034, Russian Federation article info abstract Article history: To assess the effects of interspecific interactions on community structure it is necessary to identify their sign. Received 24 December 2011 Interference in sessile benthic suspension-feeders is mediated by space and food. In the White Sea solitary Received in revised form 3 November 2012 entoproct Loxosomella nordgaardi almost restrictively inhabits the colonies of several bryozoans, including Accepted 7 November 2012 Tegella armifera. Since both entoprocts and their hosts are suspension-feeders, this strong spatial association Available online xxxx suggests feeding interference of an unknown sign. We mapped the colonies of T. armifera inhabited by entoprocts and examined stomachs of both species for Keywords: Bryozoa diatom shells. Distribution of L. nordgaardi was positively correlated with distribution of fully developed Commensalism and actively feeding polypides of T. armifera, i.e. areas of strong colony-wide currents. We compared diatom Entoprocta shells found in their stomachs and observed a diet overlap, especially in the size classes b15 μm. Size spectra Epibiosis of the diatom shells consumed by T. armifera and average number of diatom shells per gut were not affected Interactions by the presence of L. nordgaardi. According to these results, L. nordgaardi is a commensal of T. -

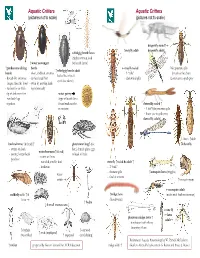

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Helminth Parasites (Trematoda, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) of Herpetofauna from Southeastern Oklahoma: New Host and Geographic Records

125 Helminth Parasites (Trematoda, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) of Herpetofauna from Southeastern Oklahoma: New Host and Geographic Records Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Charles R. Bursey Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University-Shenango, Sharon, PA 16146 Matthew B. Connior Life Sciences, Northwest Arkansas Community College, Bentonville, AR 72712 Abstract: Between May 2013 and September 2015, two amphibian and eight reptilian species/ subspecies were collected from Atoka (n = 1) and McCurtain (n = 31) counties, Oklahoma, and examined for helminth parasites. Twelve helminths, including a monogenean, six digeneans, a cestode, three nematodes and two acanthocephalans was found to be infecting these hosts. We document nine new host and three new distributional records for these helminths. Although we provide new records, additional surveys are needed for some of the 257 species of amphibians and reptiles of the state, particularly those in the western and panhandle regions who remain to be examined for helminths. ©2015 Oklahoma Academy of Science Introduction Methods In the last two decades, several papers from Between May 2013 and September 2015, our laboratories have appeared in the literature 11 Sequoyah slimy salamander (Plethodon that has helped increase our knowledge of sequoyah), nine Blanchard’s cricket frog the helminth parasites of Oklahoma’s diverse (Acris blanchardii), two eastern cooter herpetofauna (McAllister and Bursey 2004, (Pseudemys concinna concinna), two common 2007, 2012; McAllister et al. 1995, 2002, snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina), two 2005, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014a, b, c; Bonett Mississippi mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum et al. 2011). However, there still remains a hippocrepis), two western cottonmouth lack of information on helminths of some of (Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma), one the 257 species of amphibians and reptiles southern black racer (Coluber constrictor of the state (Sievert and Sievert 2011). -

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C. BEAVER, Ph.D. AMONG ANIMALS in general there is a In the development of our concepts of larva II. wide variety of parasitic infections in migrans there have been four major steps. The which larval stages migrate through and some¬ first, of course, was the discovery by Kirby- times later reside in the tissues of the host with¬ Smith and his associates some 30 years ago of out developing into fully mature adults. When nematode larvae in the skin of patients with such parasites are found in human hosts, the creeping eruption in Jacksonville, Fla. (6). infection may be referred to as larva migrans This was followed immediately by experi¬ although definition of this term is becoming mental proof by numerous workers that the increasingly difficult. The organisms impli¬ larvae of A. braziliense readily penetrate the cated in infections of this type include certain human skin and produce severe, typical creep¬ species of arthropods, flatworms, and nema¬ ing eruption. todes, but more especially the nematodes. From a practical point of view these demon¬ As generally used, the term larva migrans strations were perhaps too conclusive in that refers particularly to the migration of dog and they encouraged the impression that A. brazil¬ cat hookworm larvae in the human skin (cu¬ iense was the only cause of creeping eruption, taneous larva migrans or creeping eruption) and detracted from equally conclusive demon¬ and the migration of dog and cat ascarids in strations that other species of nematode larvae the viscera (visceral larva migrans). In a still have the ability to produce similarly the pro¬ more restricted sense, the terms cutaneous larva gressive linear lesions characteristic of creep¬ migrans and visceral larva migrans are some¬ ing eruption.