Reaction to Religious Elements in the Poetry of Robert Browning: an Introduction and Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Arctic Exploration and the Explorers of the Past

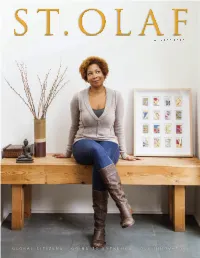

st.olafWiNtEr 2013 GLOBAL CITIZENS GOING TO EXTREMES OLE INNOVATORS ON ThE COvER: Vanessa trice Peter ’93 in the Los Angeles studio of paper artist Anna Bondoc. PHOtO By nAnCy PAStOr / POLAriS ST. OLAF MAGAzINE WINTER 2013 volume 60 · No. 1 Carole Leigh Engblom eDitOr Don Bratland ’87, holmes Design Art DireCtOr Laura hamilton Waxman COPy eDitOr Suzy Frisch, Joel hoekstra ’92, Marla hill holt ’88, Erin Peterson, Jeff Sauve, Kyle Schut ’13 COntriButinG writerS Fred J. Field, Stuart Isett, Jessica Brandi Lifl and, Mike Ludwig ’01, Kyle Obermann ’14, Nancy Pastor, Tom Roster, Chris Welsch, Steven Wett ’15 COntriButinG PHOtOGrA PHerS st. olaf Magazine is published three times annually (winter, Spring, Fall) by St. Olaf College, with editorial offi ces at the Offi ce of Marketing and Com- 16 munications, 507-786-3032; email: [email protected] 7 postmaster: Send address changes to Data Services, St. Olaf College, 1520 St. Olaf Ave., Northfi eld, MN 55057 readers may update infor- mation online: stolaf.edu/alumni or email alum-offi [email protected]. Contact the Offi ce of Alumni and Parent relations, 507- 786-3028 or 888-865-6537 52 Class Notes deadlines: Spring issue: Feb. 1 Fall issue: June 1 winter issue: Oct. 1 the content for class notes originates with the Offi ce of Alumni and Parent relations and is submitted to st. olaf Magazine, which reserves the right to edit for clarity and space constraints. Please note that due to privacy concerns, inclusion is at the discretion of the editor. www.stolaf.edu st.olaf features Global Citizens 7 By MArLA HiLL HOLt ’88 St. -

Metamorphosis: from Light Verse to the Poetry of Witness by Maxine Kumin from the Georgia Review, Winter 2012

Metamorphosis: From Light Verse to the Poetry of Witness by Maxine Kumin from The Georgia Review, Winter 2012 How did I become a very old poet, and a polemicist at that? In the Writers Chronicle of December 2010 I described myself as largely self-educated. In an era before creative writing classes became a staple of the college curriculum, I was "piecemeal poetry literate"—in love with Gerard Manley Hopkins and A. E. Housman, an omnivorous reader across the centuries of John Donne and George Herbert, Randall Jarrell and T. S. Eliot. I wrote at least a hundred lugubrious romantic poems. One, I remember, began When lonely on an August night I lie Wide-eyed beneath the mysteries of space And watch unnumbered pricks of dew-starred sky Drop past the earth with quiet grace ... Deep down I longed to be one of the tribe but I had no sense of how to go about gaining entry. I had already achieved fame in the narrow confines of my family for little ditties celebrating birthdays and other occasions, but I did not find this satisfying. There were no MFAs in poetry that I knew of except for the famous Iowa Writers' Workshop, founded in 1936; certainly there was nothing accessible to a mother of two, pregnant with her third child in 1953 in Newton, Massachusetts. I have noted elsewhere that I chafed against the domesticity in which I found myself. I had a good marriage and our two little girls were joyous elements in it. But my discontent was palpable; I did not yet know that a quiet revolution in thinking was taking place. -

At the Intersection of Poetry and a Lower

At the Intersection of Poetry and a High School English Class: 9th Graders‟ Participation in Poetry Reading Writing Workshop and the Relation to Social and Academic Identities‟ Development DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan Koukis Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Anna Soter, Advisor George Newell Mollie Blackburn Terry Hermsen Copyright by Susan Koukis 2010 Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine whether “marginalized” (Moje, Young, Readence, & Moore 2000) 9th grade students in a low-level, tracked English class perceived themselves as more successful students in English class after participating in a 10-week Poetry Reading Writing Workshop. A second purpose was to determine whether their knowledge of poetry terms and concepts such as metaphor, and subsequent performance on the poetry sections of standardized tests improved. My nested case study focused on 19 students in a low-level 9th grade English class. As the practitioner researcher, I conducted in- depth research with six focus students chosen through purposeful sampling. I collected data over the course of three months, using the types of instruments most common to case study research. Data analysis for my nested case study was ongoing and recursive between field work and reflection. Data were coded for patterns that represented categories pertaining to my research questions and coding was refined as I gathered and re-read additional data sources. The findings revealed that students learn better, and are more engaged when they have choices (Atwell, 1998; Lauscher, 2007). -

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God Is the Perfect Poet

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God is the perfect poet. – Paracelsus by Robert Browning NUMBER 51 SPRING/SUMMER 2007 WACO, TEXAS Ann Miller to be Honored at ABL For more than half a century, the find inspiration. She wrote to her sister late Professor Ann Vardaman Miller of spending most of the summer there was connected to Baylor’s English in the “monastery like an eagle’s nest Department—first as a student (she . in the midst of mountains, rocks, earned a B.A. in 1949, serving as an precipices, waterfalls, drifts of snow, assistant to Dr. A. J. Armstrong, and a and magnificent chestnut forests.” master’s in 1951) and eventually as a Master Teacher of English herself. So Getting to Vallombrosa was not it is fitting that a former student has easy. First, the Brownings had to stepped forward to provide a tribute obtain permission for the visit from to the legendary Miller in Armstrong the Archbishop of Florence and the Browning Library, the location of her Abbot-General. Then, the trip itself first campus office. was arduous—it involved sitting in a wine basket while being dragged up the An anonymous donor has begun the cliffs by oxen. At the top, the scenery process of dedicating a stained glass was all the Brownings had dreamed window in the Cox Reception Hall, on of, but disappointment awaited Barrett the ground floor of the library, to Miller. Browning. The monks of the monastery The Vallombrosa Window in ABL’s Cox Reception The hall is already home to five windows, could not be persuaded to allow a woman Hall will be dedicated to the late Ann Miller, a Baylor professor and former student of Dr. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

Guide to the Papers of the Summer Seminar of the Arts

Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Guide to the Papers of The Summer Seminar of the Arts Auburn University at Montgomery Library Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2 Biographical Information 3-4 Scope and Content Note 5 Arrangement 5-6 Inventory 6-24 1 Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Collection Summary Creator: Jack Mooney Title: Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Dates: ca. 1969-1983 Quantity: 9 boxes; 6.0 cu. ft. Identification: 2005/02 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: Jack Mooney donated the collection to the AUM Library in May 2005. Processing By: Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant (2005). Copyright Information: Copyright not assigned to the AUM Library. Restrictions Restrictions on access: There are no restrictions on access to these papers. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. 2 Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Biographical/Historical Information The Summer Seminar of the Arts was an annual arts and literary festival held in Montgomery from 1969 until 1983. The Seminar was part of the Montgomery Arts Guild, an organization which was active in promoting and sponsoring cultural events. Held during July, the Seminar hosted readings by notable poets, offered creative writing workshops, held creative writing contests, and featured musical performances. -

Eco-Migration: Shakespeare and the Contemporary Novel

SAA 2021: Ecomigration: Shakespeare and the Contemporary Novel Seminar Organizer: Sharon O’Dair, University of Alabama Abstracts. Walter Cohen University of Michigan SAA 2021 Historical Novel (and other genres) of Early Modern World (1450-1700) Key issues a. History/temporality i. Renaissance vs. other periods as object of historical representation. Do you get anything different from delimiting the historical novels under scrutiny to the early modern period—i.e. anything different from historical novels about other periods? This question asks us to compare the historical novels in this study grouping to historical novels about Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the 18th-mid 20th century. ii. Different periods in which accounts of Renaissance are composed. Do you get anything different from delimiting the historical novels under scrutiny to the early modern period—i.e. anything different from seeing realism- modernism-postmodernism as successive forms of the historical novel? This question asks us to compare the historical novels in this grouping to each other along the historical/formalist lines of the three obvious periods of the historical novel. It uses Perry Anderson’s 2011 survey of the historical novel as a baseline for comparison. iii. Composite account of the era? What if you keep the different times when the novels were written, the different genres (realism-modernism- postmodernism), the different languages in which they’re written, and the different places and events they treat all in the background? Instead, we ask: what do we get from reading these novels as a composite account of the era? Is it different from what we get from a more familiar history of the historical novel (Lukács-Anderson) and/or from the current state of historiography of the period? How is it inflected by early modern writers themselves—above all Shakespeare? b. -

To the EDITOR of the CLASSICAL REVIEW

THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. 61 then a few of the by-ways. Mr. Browning ling of Admetus's story, and Ixion (Jocoseria), used to know every inch of one highway with its conversion of the transgressor with all its associated by-ways, and never into a newer and more human Prometheus. set his foot on any other highway in the But also there is a word in Gerard de Loiresse same region. If he had been a zoologist, he {Parleyings) for those who might think that would have known all about lions and no- we must go back to myths for all our poetry. thing about tigers. Of course, this is no dis- Outlying stories that he found in his great paragement to his greatness. His true field researches are worked up in EcJietlos and was not learning but life. Only, why could Pfieidippides. He is still constant to the he not have read some Plato ? Our wistful Aeschylus of his youth, and especially to fancy cannot help framing some shadow of the PrometJieus, and to these he adds Pindar the transformed Republic and interpreted and Homer, quoting all three in Roman P/taedrus, for which we could have spared, letters in the midst of his verse. From perhaps, the refutation of Bubb Doding- Homer he is led to consider the ' Homeric ton and the divagations of the Famille question,' and uses it characteristically to Miranda. show forth in allegory the religious edu- Besides interpreting Greek tragedy, he cation of mankind (Asolando, Developments). translated it. The translations of the Alceslis In this period, for the first time in his life, (in Balaustion) and the Hercules Furens (in he begins to add Latin to Greek. -

The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning's Dramatic Monologues

Előd Pál Csirmaz The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues MA Thesis (for MA in English Language and Literature) Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary, 2006 Supervisor: Péter Dávidházi, Habil. Docent, DSc. Abstract Even after the death of the Author, its remains, its tomb appears to mark a text it cre- ated. Various readings and my analyses of Robert Browning’s six dramatic mono- logues, My Last Duchess, The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church, Andrea del Sarto, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” Caliban upon Setebos and Rabbi Ben Ezra, suggest that it is not only possible to trace Authorial presence in dramatic monologues, where the Author is generally supposed to be hidden behind a mask, but often it even appears to be inevitable to consider an Authorial entity. This, while problematizes traditional anti-authorial arguments, do not entail the dreaded consequences of introducing an Author, as various functions of the Author and vari- ous Author-related entities are considered in isolation. This way, the domain of metanarrative-like Authorial control can be limited and the Author is turned from a threat into a useful tool in analyses. My readings are done with the help of notions and suggestions derived from two frameworks I introduce in the course of the argument. They not only help in tracing and investigating the Author and related entities, like the Inscriber or the Speaker, but they also provide an alternative description of the genre of the dramatic monologue. Előd P Csirmaz The Tomb of the Author ii Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE THEORY OF THE AUTHOR 1 2.1 A History of the Death of the Author 2 2.2 From the Methodological to the Ontological and Back: The Functions of the Author and its Death 3 A. -

Religions and Legal Boundaries of Democracy in Europe: European Commitment to Democratic Principles

Religions and legal boundaries of democracy in Europe: European commitment to democratic principles University of Helsinki, 2009 Religions and legal boundaries of democracy in Europe: European commitment to democratic principles Dorota A. Gozdecka Academic Dissertation To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Law of the University of Helsinki for public examination in the Auditorium of the Helsinki University Museum Arppeanum (Snellmaninkatu 3, Helsinki) on 7 November 2009 at 10 a.m. supervisor: Adjunct Professor Ari Hirvonen, University of Helsinki preliminary examiners: Professor Kimmo Nuotio, University of Helsinki Associate Professor Lisbet Christoffersen, University of Roskilde opponent: Professor Zenon Bankowski, University of Edinburgh Language edition: Doctor Joan Löfgren, University of Tampere Graphic design: Ville Sutinen Cover painting: Anna Kozar-Poikonen Copyright © 2009 Dorota A. Gozdecka ISBN 978-952-92-6256-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-5803-5 (PDF) http://ethesis.helsinki.fi University of Helsinki 2009 I dedicate this book to my parents as an expression of appreciation for their constant support of my scientific endeavours. Pracę tę dedykuję moim rodzicom, z podziękowaniami za wkład, jaki włożyli w proces mojej edukacji i wsparcie dla moich naukowych wysiłków. Abstract This dissertation’s main research questions concern common European principles of democracy in regard to religious freedom. It deals with the modern understanding of European democracy and is a combination of interdisciplinary research on law, culture, politics and philosophy. The main objective of this research is to identify common European legal principles and standards applying to religious freedom and compare them with standards and approaches in particular states. The bases for the analysis are the principles of equality and achievement of religious pluralism. -

The Qualities of Browning

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mid-West Quarterly, The (1913-1918) Mid-West Quarterly, The (1913-1918) 1914 The Qualities of Browning Harry T. Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/midwestqtrly Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Baker, Harry T., "The Qualities of Browning" (1914). Mid-West Quarterly, The (1913-1918). 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/midwestqtrly/43 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mid-West Quarterly, The (1913-1918) at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mid-West Quarterly, The (1913-1918) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE MID-WEST QUARTERLY 2:1 (October 1914), pp. 57-73. Published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons & the University of Nebraska. THE QUALITIES OF BROWNING I The opening lines of Pippa Passes pulse with the tremendous vitality which the reader of Browning has early learned to expect of his poetry: "Day! Faster and more fast, O'er night's brim day boils at last: Boils, pure gold, o'er the cloud-.cup's brim Where spurting and suppressed it lay, For not a froth-flake touched the rim Of yonder gap in the solid gray Of the eastern cloud, an hour away; But forth one wavelet, then another, curled, Till the whole sunrise, not to be suppressed, Rose, reddened, and its seething breast Flickered in bounds, grew gold, then overflowed the world." Of this remarkable vital force the last poem from his pen, the Epilogue to Asolando, shows no diminution.