Title Page.FH10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamil Khan Mumtaz in Pakistan

A Contemporary Architectural Quest and Synthesis: Kamil Khan Mumtaz in Pakistan by Zarminae Ansari Bachelor of Architecture, National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan, 1994. Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1997 Zarminae Ansari, 1997. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. A uthor ...... ................................................................................. .. Department of Architecture May 9, 1997 Certified by. Attilio Petruccioli Aga Khan Professor of Design for Islamic Culture Thesis Supervisor A ccep ted b y ........................................................................................... Roy Strickland Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture JUN 2 0 1997 Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MIT Libraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://Ilibraries.mit.eduldocs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Some pages in the original document contain color / grayscale pictures or graphics that will not scan or reproduce well. Readers: Ali Asani, (John L. Loeb Associe e Professor of the Humanities, Harvard Univer- sity Faculty of Arts and Sciences). Sibel Bozdogan, (Associate Professor of Architecture, MIT). Hasan-ud-din Khan, (Visiting Associate Professor, AKPIA, MIT). -

IVCC CONSULTANTS LIST Ser No

IVCC ENGINEERING (PVT) LTD. Email: [email protected] IVCC CONSULTANTS LIST Ser No. Name of Consultants Country 1 Agro Complet, Sofia. BULGARIA 2 Akbar & Aleem, Karachi. PAKISTAN 3 Al-Saadi Technical & Management Consultants, Lahore. PAKISTAN 4 Allied Engineering Corporation Ltd., Lahore. PAKISTAN 5 Associated Consulting Engineers Ltd., Lahore. PAKISTAN 6 Axons Associates Architects & Engineers, Lahore. PAKISTAN 7 Barqaab Consulting Services (Pvt) Ltd. PAKISTAN 8 Basha Diamer Consultants. PAKISTAN 9 Bashir & Associates, Karachi. PAKISTAN 10 Binnie & Partners, London. U.K. 11 Carrier Associates Ltd., Rawalpindi. PAKISTAN 12 Chas.T.Main Inc., New York. U.S.A. 13 Chashma Group of Consultants Lahore. PAKISTAN 14 Commonwealth Associates Ltd. CANADA 15 Coode and Partners, London. U.K. 16 Coyneet Bellier, Paris. FRANCE 17 Diamer Basha Consultants Lahore PAKISTAN 18 Dorsch Consult Munic and K.f.W. GERMANY 19 Electroconsult (ELC), Rome. ITALY 20 Energoprojekt, Belgrade. YUGOSLAVIA 21 Engineering Consultants International (Pvt) Ltd., Karachi. PAKISTAN 22 Freeman Fox & Partners, London. U.K. 23 Habib Fida Ali, Karachi. PAKISTAN 24 Harza Engineering International Inc., Chicago. U.S.A. 25 Hatch Associates Proprietary Limited. AUSTRALIA 26 Industrial and Cement Engineers Ltd. (INCEM), Lahore. PAKISTAN 27 Kalabagh Consultants, Lahore. PAKISTAN 28 Korea Consultants International, Seoul. SOUTH KOREA 29 Mangla Joint Venture, Lahore. PAKISTAN 30 Meinhardt (Pakistan) Private Ltd., Karachi. PAKISTAN 31 Meinhardt (Singapore) Pte Ltd. SINGAPORE 32 Montreal Engineering Co. Ltd., Montreal. CANADA 33 Muzaffargarh Thermal Power Consultants, Lahore. PAKISTAN 34 MWS Consultants Inc. Illinois. U.S.A. 35 National Development Consultants (NDC) Lahore. PAKISTAN 36 National Engineering Services Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd., Lahore. PAKISTAN 37 Nayyar Ali Dada & Associates, Lahore. -

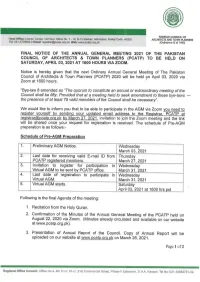

AGM Report 2019-2020

Pakistan Council of Architects and Town Planners ANNUAL REPORT2019 P A K I S T A N C O U N C I L O F ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS PAKISTAN COUNCIL OF ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Presented at Annual General Meeting 2020 Date: August 22nd, 2020 PAKISTAN COUNCIL OF ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS HEAD OFFICE: Office No.7-12, First Floor, Usman Center D-12 Markaz, Islamabad-45200 Page | 1 P A K I S T A N C O U N C I L O F ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS Table of Contents Chapter 1 PCATP ––Executive Committee 2019-2021 Chapter 2 Summary of Important Activities during March 01, 2019–June 30, 2020 Chapter 3 PCATP Finance and Accounts List of Annexures Annex A Minutes of the Annual General Meeting held on March08, 2019. Annex B Detailed Expenditures on Purchase and Establishment of PCATP Head Office Islamabad Annex C Policy guidelines for Online Teaching-Learning and Assessment Implementation Annex D Thesis guidelines for graduating batch during COVID-19 pandemic Annex E Inclusion of PCATP in NAPDHA Annex F Inclusion of role of Architects and Town Planners in the CIDB Bill 2020 Annex G Circulation List for Compliance of PCATP Ordinance IX of 1983 Status of Institutions Offering Architecture and Town Planning Annex H Undergraduate Degree Programs in Pakistan Annex I List of Registered Members and Firms who have contributed towards COVID-19 Fund in PCATP Account Annex J List of Registered Members and Firms who have contributed towards COVID-19 Fund in IAP Account Annex K Audited Accounts and Balance Sheet of PCATP General Fund and RHS Account for the Year 2018-2019 Page | 2 P A K I S T A N C O U N C I L O F ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS CHAPTER 1 PCATP EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2019 – 2021 During the year under report, the present Executive Committee 2019-2021 held five meetings. -

Quddus Mirza

THE ARTNOW PAPER www.artnowpakistan.com VOL IV 2019 Saleha Arif, National College of Arts Rawalpindi Thesis Display, 2018. Image courtesy the artist Connecting Flights Profile | October 2018 Photo Essay | November 2018 In Focus | January 2019 Profile | January 2019 Regional modernist at heart: Disrupting Navigation of an Nayyer Ali Dada emotional minefield UBERMENSCH nature’s course Through this navigation of an emotional On the Pakistani artscape, Rana Rashid Dada has always been a modernist at The relationship Karachi shares with its edge: minefield, one also must focus on the rocketed like nothing less than a super- heart, though his style has evolved from both the good and the bad... the escape it business of the day… man. I listen to Rana’s impassioned ideas that to a regional modernist... offers and their indifference to it all... the Degree Show... about art-making and art education... Pages 12-13 Page 26 Pages 30-31 Pages 6-8 2019 ARTNOW PAKISTAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLICATION DESIGN BY JOVITA ALVARES Editorial Note Editorial Note Fawzia Naqvi Quddus Mirza Editor in Chief Editor Welcome to another edition of the ArtNow Art Newspaper, At the degree show of an art institute, it is realised that we are bringing to our readers selected articles from the online mag- heir to human legacy, in art, literature, science, technology azine in print form. Our theme for this edition is “Thesis Dis- and other fields of knowledge and culture. Everything created, plays”, as some very exciting Degree Shows have taken place over the past two months at conceived and constructed by humankind is our past and part of our heritage. -

CAMPUS STORIES Volume 1 Issue 1

CAMPUS STORIES Volume 1 Issue 1 Follow the LUMS journey: from a single house to a sprawling campus Faculty and staff share snippets from The LUMS their work from Community home life welcomes new leadership CAMPUS STORIES CONTENTS 5 Welcoming New Leadership Snapshots of the Work from 8 Home Life 10 Convocation 2020; A Virtual LUMS Steps Up to Face Celebration 2 the Pandemic In Conversation with A Tribute to Our the VC and Outgoing The Creator’s Studio 19 12 15 Outgoing Deans Provost 21 How can you Help? 16 The LUMS Legacy MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR I am delighted to introduce you to the times, our LUMS family has risen to inaugural issue of Campus Stories, a the challenge and demonstrated magazine which aims to celebrate the exemplary resilience and commitment. University and engage with members It is precisely this spirit of unity that this of our internal community, particularly publication aims to celebrate. faculty and staff. Through this platform, In our next issue, we look forward we would like to showcase the to including more stories from our Editorial tremendous amount of work that is community. You can help us improve being done across our five schools this magazine by offering feedback on Board and many departments. This is a great content or by suggesting an article for opportunity for us to strengthen our Deputy Manager Communications a future edition at communications@ bond, come closer together and get to Khuzaima Fatima Azam lums.edu.pk. Until we connect again, know more about each other and our I hope you and your family members different roles. -

Colonial Encounters, Karachi and Anglo-Indian Dwellings During the Raj

COLONIAL ENCOUNTERS, KARACHI AND ANGLO-INDIAN DWELLINGS DURING THE RAJ A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY NIDA AHMED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE JANUARY 2017 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Tulin GENÇÖZ Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Elvan ALTAN Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN Supervisor Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Belgin T. ÖZKAYA (METU, AH) Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, AH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Namık G. ERKAL (TEDU, Arch.) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Nida Ahmed Signature : iii ABSTRACT COLONIAL ENCOUNTERS, KARACHI AND ANGLO‐INDIAN DWELLINGS DURING THE RAJ AHMED, Nida M.A., Department of History of Architecture Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Suna Güven January 2017, 156 pages Was British imperialism in India an authoritarian rule or a collaborative one? How did the Indians resist, react, or adapt to the modernity introduced by the British? How did the British respond to their Indian context? Did the colonisers transplant western ideology and institutions without experiencing an exchange of ideas and practices in return? To deal with these questions, the study focuses on the architectural developments in Karachi during the British Raj (1858‐1947) and investigates how the reforms introduced by the Raj transformed and modernised the society and its architecture, particularly the colonial domestic architecture. -

BS + Master of Architecture Dual Degree)

Roger Williams University School of Architecture, Art and Historic Preservation Architecture Program Report Master of Architecture (BS + Master of Architecture dual degree) Donald J. Farish, Ph.D., J.D., President Robert A. Potter, Ph.D., Interim Provost Program Administrator: Stephen White, AIA, Dean, [email protected] , (401) 254-3607 Curriculum Coordination: Edgar Adams, RA, Professor Submitted to: The National Architectural Accrediting Board September 2011/Updated December 2011/March 2012 Table of Contents Section Page Part I. Institutional Support and Commitment to Continuous Improvement 1. Identity and Self-Assessment 1.1 History and Mission 1 1.2 Learning Culture and Social Equity 11 1.3 Response to the Five Perspectives 21 1.4 Long-Range Planning 31 1.5 Self-Assessment Procedures 36 2. Resources 2.1 Human Resources & Human Resource Development 50 2.2 Administrative Structure & Governance 79 2.3 Physical Resources 83 2.4 Financial Resources 89 2.5 Information Resources 92 3. Institutional and Program Characteristics 3.1 Statistical Reports 100 3.2 Annual Reports 121 3.3 Faculty Credentials 122 4. Policy Review 136 Part II. Educational Outcomes and Curriculum 1. Student Performance Criteria 137 2. Curricular Framework 2.1 Regional Accreditation 143 2.2 Professional Degrees and Curriculum 146 2.3 Curriculum Review and Development 156 3. Evaluation of Preparatory/ Pre-Professional Education 165 4. Public Information 168 4.1 Statement on NAAB-Accredited Degrees 4.2 Access to NAAB Conditions and Procedures 4.3 Access to Career Development Information 4.4 Public Access to APR’s and VTR’s 4.5 ARE Pass Rates Part III. -

Investigating the Emergence and Performance of Shopping Malls from Design Review and Users’ Perspectives in Karachi, Pakistan

International Research Journal of Architecture and Planning Vol. 5(1), pp. 111-122, March, 2020. © www.premierpublishers.org. ISSN: 1530-9931 Research Article Investigating the Emergence and Performance of Shopping Malls from Design Review and Users’ Perspectives in Karachi, Pakistan *Fariha Tahseen1, Prof. Dr. Noman Ahmed2 1Lecturer, Department of Architecture and Planning, NED University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi 2 Professor, Department of Architecture and Planning, NED University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi This paper is based on a study that investigates emergence and performance of shopping malls from design review and users’ experience. It examines users’ expectancy of services and their level of satisfaction, thus, influences overall performance evaluation of a shopping mall. This research paper also explores emergence of shopping malls in Karachi and a concise account of identifying challenges and exploring opportunities. The research methodology employs qualitative mode of research design for data collection through multiple methods such as on-site investigation by observations, and acquiring user perception by questionnaires and interviews. The data analysis comprises of calculation of customer satisfaction index (CSI) and SPSS statistics tests. Firstly, an overall trend in performance was evaluated. Secondly, it was found if there is statistically significant difference in performance between 5 selected shopping malls of Karachi based on incorporation of design considerations and attributes of a) location and accessibility b) parking and circulation c) site planning and landscape d) design features and services. A proposal of recommendations, as guiding ethos, to minimize impacts of identified challenges in malls of Pakistan concludes this paper. Keywords: Shopping Malls, Mall Emergence and Development, Performance attributes, Customer Satisfaction, Challenges and Opportunities, Design Considerations, Building Evaluation INTRODUCTION Shopping malls, widely accepted as a global phenomenon, development as multi user spaces. -

AGM Report 2021

PAKISTAN COUNCIL OF ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Presented at Annual General Meeting 2021 Date: March, 2021 PAKISTAN COUNCIL OF ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS HEAD OFFICE: Office No.7-12, 1st Floor, Usman Center D-12 Markaz, Islamabad-45200 P A K I S T A N C O U N C I L O F ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS Table of Contents Chapter 1 PCATP ––Executive Committee 2019-2021 Chapter 2 Summary of Important Activities during July 01 2020–March 11, 2021 Chapter 3 PCATP Finance and Accounts List of Annexures Annex-A Minutes of the Annual General Meeting held on August 22, 2020. Annex-B Leagal Notice to Capital Development Authority (CDA), Islamabad Annex-C Legal Notice to Walton Cantonment Board, Lahore Annex-D Audited Accounts and Auditor’s Report on Pcatp General Funds for the Financial Year 2019-2020 P A K I S T A N C O U N C I L O F ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS CHAPTER 1 PCATP EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2019 – 2021 During the year under report, the present Executive Committee 2019-2021 held four meetings. Three meetings were held virtually on zoom (video-conferencing software). Following is the list of meetings attended by Executive Committee members: No. of Meetings Held 17-Oct- 28-Nov- Meetings S.No Name 18-Jul-20 20 20 Attended 1 Ar. /Plnr. Kalim A.Siddiqui P P P 3 2 Ar. Amir Nazir Chaudhary P P A 2 3 Plnr. Khurram Faird P P P 3 4 Prof. Dr. Samra Mohsin Khan P P P 3 5 Ar. -

Hasan-Uddin Khan Distinguished Professor of Architecture and Historic Preservation Full Time

Name: Hasan-Uddin Khan Distinguished Professor of Architecture and Historic Preservation Full Time Courses Taught: Arch 515 Graduate Architecture Design Studio Arch 541 & Arch 613 Graduate Research Seminar & Thesis Studio Arch 530 Special Topics: Contemporary Architecture in Asia and Africa HP 351 History and Philosophy of Historic Preservation HP 631 & HP 651 Graduate Thesis Research Seminar & Graduate Thesis Educational Credentials: Diploma, Architectural Association, London 1972 Teaching Experience: Distinguished Professor of Architecture and Historic Preservation RWU 1999- Visiting Professor of Architecture, University of California, Berkeley Spring 1999, 2007 Visiting Associate Professor of Architecture, MIT 1994–99 Professional Experience: Advisory Committee and Board of Directors, University of the Middle East 2003 – Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Geneva, Director of Special Projects and Outreach 1991–94 Getty Grant Program Advisory Committee, Rome Prize, Int’l Competition Juries 1988 – Head of Architectural Activities at the Secretariat of His Highness the Aga Khan, France 1984–91 Founder and Editor-in-Chief, Mimar: Architecture in Development 1981–92 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Convener, 1977-80, Steering Committee, Paris 1981–89 Unit 4, Principal in private practice in Karachi, Pakistan, and occasional practice 1974-76, 2007– Payette Associates and Gerald Shenstone and Partners, London, UK 1972–74 Licenses/Registration: Pakistan, UK Selected Publications and Recent Research: Books: Author (and/or editor) of nine books, including – Habib Fida Ali: Architect of Pakistan, Karachi, 2011 The Middle East, Architecture 1900-2000. Vienna and New York 2001 International Style: Modern Architecture 1925-1965, Cologne 1998 The Mosque and the Modern World, co-author, London and New York 1997 Articles: over 60 published 1972 Current Research: Globalization and Urbanism in Asia, 20th C. -

Searching for Identity: the Approaches of Three Pakistani Architects

Searching For Identity: The Approaches of Three Pakistani Architects by NADIR MOHAMMAD KHAN B.Arch., The National College of Arts Lahore, Pakistan June 1987 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1990 @ Nadir M. Khan, 1990 All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of the Author Nadir M. Khan (N y Dep ePt of Architecture, 11th May 1990 Certified by- William Porter Thesis Supervisor. Head Department of Architecture Accepted by Charma C i Julian Beinart 'JotC chairman Defantal Committee for Graduate Students i AY 3 0 1990 LIBRARIES Pacte 2 0 11 -F,--1 V T AO~n f- 1-e, Searching for Identity: The Approaches of Three Pakistani Architects by Nadir M. Khan Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 11, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies. ABSTRACT This thesis attempts to deal with some of the major issues relating to Pakistani architecture today as well as the consequent development of an architectural identity. In order to establish the framework for the study various discourses that reflect on the notion of identity have been examined. Due to the lack of an indigenous architectural discourse, and the consequent absence of critically rigorous information on the subject, this work is devoted to augmenting the very limited material available on the state of the architectural profession in Pakistan and to increasing an awareness of the directions that this architecture is presently taking. -

Architecture and History in Pakistan

Building, Dwelling, Dying: Architecture and History in Pakistan Chris Moffat, [email protected] School of History, Queen Mary University of London Published in Modern Intellectual History (2020) Abstract There is a long history of scholars finding in architecture tools for thinking, whether this is the relationship between nature and culture in Simmel’s ruins, industrial capitalism in Benjamin’s Parisian arcades, or the rhythms of the primordial in Heidegger’s Black Forest farmhouse. But what does it mean to take seriously the concepts and dispositions articulated by architects themselves? How might processes of designing and making constitute particular forms of thinking? This article considers the words and buildings of Lahore-based architect Kamil Khan Mumtaz (b.1939) as an entry-point to such questions. It outlines how professional architecture in Pakistan has grappled with the unsettled status of the past in a country forged out of two partitions (1947 and 1971). Mumtaz’s work and thought – engaging questions of tradition, authority, craft and the sacred – demonstrates how these predicaments have been productive for conceptualising time, labour and the nature of dwelling in a postcolonial world. MOFFAT | BUILDING, DWELLING, DYING 2 I. Architecture and History Pakistan as place and idea poses some provocative problems for the philosophy and anthropology of history. Established in 1947 less than a decade after its emergence as a political goal, the sovereign state of Pakistan represented a rupture in South Asian history. Premised on separatist claims to ‘nationality’ status, it was also a break from historical forms of Muslim political thought and identity in the region, which had in the early twentieth century gravitated toward ideas of imperial pluralism, elite stewardship or the possibility of minority status within a broader community.1 The postcolonial polity carved out of colonial India would fracture again in 1971, when a mass movement in the country’s eastern wing fought an independence war to establish Bangladesh.