Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ailanthus Excelsa Roxb

Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Simaroubaceae maharukh LOCAL NAMES Arabic (ailanthus,neem hindi); English (ailanthus,coramandel ailanto,tree- of-heaven); Gujarati (aduso,ardusi,bhutrakho); Hindi (maharuk,ardu,ardusi,arua,horanim maruk,aduso,mahanim,mahrukh,maruf,pedu,Pee vepachettu,pir nim); Nepali (maharukh); Sanskrit (madala); Tamil (periamaram,peru,perumaran,pimaram,pinari); Trade name (maharukh) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Ailanthus excelsa is a large deciduous tree, 18-25 m tall; trunk straight, 60-80 cm in diameter; bark light grey and smooth, becoming grey-brown and rough on large trees, aromatic, slightly bitter. Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, large, 30-60 cm or more in length; leaflets 8-14 or more pairs, long stalked, ovate or broadly lance shaped from very unequal base, 6-10 cm long, 3-5 cm wide, often curved, long pointed, hairy gland; edges coarsely toothed and often lobed. Flower clusters droop at leaf bases, shorter than leaves, much branched; flowers many, mostly male and female on different trees, short stalked, greenish-yellow; calyx 5 lobed; 5 narrow petals spreading 6 mm across; stamens 10; on other flowers, 2-5 separate pistils, each with elliptical ovary, 1 ovule, and slender style. Fruit a 1-seeded samara, lance shaped, flat, pointed at ends, 5 cm long, 1 cm wide, copper red, strongly veined, twisted at the base The generic name ‘Ailanthus’ comes from ‘ailanthos’ (tree of heaven), the Indonesian name for Ailanthus moluccana. BIOLOGY The flowers appear in large open clusters among the leaves towards the end of the cold season. Male, female and bisexual flowers are intermingled on the same tree. The fruits ripen just before the onset of the monsoon. -

Plant Conservation Alliance®S Alien Plant Working Group Tree of Heaven Ailanthus Altissima (Mill.) Swingle Quassia Family (Sima

FACT SHEET: TREE OF HEAVEN Tree of Heaven Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle Quassia family (Simaroubaceae) NATIVE RANGE Central China DESCRIPTION Tree-of-heaven, also known as ailanthus, Chinese sumac, and stinking shumac, is a rapidly growing, deciduous tree in the mostly tropical quassia family (Simaroubaceae). Mature trees can reach 80 feet or more in height. Ailanthus has smooth stems with pale gray bark, and twigs which are light chestnut brown, especially in the dormant season. Its large compound leaves, 1-4 feet in length, are composed of 11-25 smaller leaflets and alternate along the stems. Each leaflet has one to several glandular teeth near the base. In late spring, clusters of small, yellow-green flowers appear near the tips of branches. Seeds are produced on female trees in late summer to early fall, in flat, twisted, papery structures called samaras, which may remain on the trees for long periods of time. The wood of ailanthus is soft, weak, coarse-grained, and creamy white to light brown in color. All parts of the tree, especially the flowers, have a strong, offensive odor, which some have likened to peanuts or cashews. NOTE: Correct identification of ailanthus is essential. Several native shrubs, like sumacs, and trees, like ash, black walnut and pecan, can be confused with ailanthus. Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), native to the eastern U.S., is distinguished from ailanthus by its fuzzy, reddish-brown branches and leaf stems, erect, red, fuzzy fruits, and leaflets with toothed margins. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Tree-of-heaven is a prolific seed producer, grows rapidly, and can overrun native vegetation. -

Brisbane Native Plants by Suburb

INDEX - BRISBANE SUBURBS SPECIES LIST Acacia Ridge. ...........15 Chelmer ...................14 Hamilton. .................10 Mayne. .................25 Pullenvale............... 22 Toowong ....................46 Albion .......................25 Chermside West .11 Hawthorne................. 7 McDowall. ..............6 Torwood .....................47 Alderley ....................45 Clayfield ..................14 Heathwood.... 34. Meeandah.............. 2 Queensport ............32 Trinder Park ...............32 Algester.................... 15 Coopers Plains........32 Hemmant. .................32 Merthyr .................7 Annerley ...................32 Coorparoo ................3 Hendra. .................10 Middle Park .........19 Rainworth. ..............47 Underwood. ................41 Anstead ....................17 Corinda. ..................14 Herston ....................5 Milton ...................46 Ransome. ................32 Upper Brookfield .......23 Archerfield ...............32 Highgate Hill. ........43 Mitchelton ...........45 Red Hill.................... 43 Upper Mt gravatt. .......15 Ascot. .......................36 Darra .......................33 Hill End ..................45 Moggill. .................20 Richlands ................34 Ashgrove. ................26 Deagon ....................2 Holland Park........... 3 Moorooka. ............32 River Hills................ 19 Virginia ........................31 Aspley ......................31 Doboy ......................2 Morningside. .........3 Robertson ................42 Auchenflower -

Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’S Letter

Planning and planting for a better world Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum Newsletter Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’s Letter Spring greetings from the JC Raulston Arboretum! This garden- ing season is in full swing, and the Arboretum is the place to be. Emergence is the word! Flowers and foliage are emerging every- where. We had a magnificent late winter and early spring. The Cornus mas ‘Spring Glow’ located in the paradise garden was exquisite this year. The bright yellow flowers are bright and persistent, and the Students from a Wake Tech Community College Photography Class find exfoliating bark and attractive habit plenty to photograph on a February day in the Arboretum. make it a winner. It’s no wonder that JC was so excited about this done soon. Make sure you check of themselves than is expected to seedling selection from the field out many of the special gardens in keep things moving forward. I, for nursery. We are looking to propa- the Arboretum. Our volunteer one, am thankful for each and every gate numerous plants this spring in curators are busy planting and one of them. hopes of getting it into the trade. preparing those gardens for The magnolias were looking another season. Many thanks to all Lastly, when you visit the garden I fantastic until we had three days in our volunteers who work so very would challenge you to find the a row of temperatures in the low hard in the garden. It shows! Euscaphis japonicus. We had a twenties. There was plenty of Another reminder — from April to beautiful seven-foot specimen tree damage to open flowers, but the October, on Sunday’s at 2:00 p.m. -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Samia Cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- Place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates

________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 61, Number 4 Winter 2019 www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________________________________________ Inside: Butterflies of Papua Southern Pearly Eyes in exotic Louisiana venue Philippine butterflies and moths: a new website The Lepidopterists’ Society collecting statement updated Lep Soc, Southern Lep Soc, and Assoc of Trop Lep combined meeting Butterfly vicariance in southeast Asia Samia cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates ... and more! ________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Contents www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________ Digital Collecting -- Butterflies of Papua, Indonesia ____________________________________ Bill Berthet. .......................................................................................... 159 Volume 61, Number 4 Butterfly vicariance in Southeast Asia Winter 2019 John Grehan. ........................................................................................ 168 Metamorphosis. ....................................................................................... 171 The Lepidopterists’ Society is a non-profit ed- Membership Updates. ucational and scientific organization. The ob- Chris Grinter. ....................................................................................... 171 -

Plant Invasion As an Emerging Challenge for the Conservation of Heritage Sites: the Spread of Ornamental Trees on Ancient Monuments in Rome, Italy

Biol Invasions (2021) 23:1191–1206 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-020-02429-9 (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Plant invasion as an emerging challenge for the conservation of heritage sites: the spread of ornamental trees on ancient monuments in Rome, Italy Laura Celesti-Grapow . Carlo Ricotta Received: 30 June 2020 / Accepted: 23 November 2020 / Published online: 5 December 2020 Ó The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Cultural heritage sites such as historical or included among the invasive species of European sacred areas provide suitable habitats for plants and Union concern (EU Regulation 2019/1262). Our play an important role in nature conservation, partic- findings show that plant invasion is an emerging ularly in human-modified contexts such as urban challenge for the conservation of heritage sites and environments. However, such sites also provide needs to be prioritized for management to prevent opportunities for the spread of invasive species, whose future expansion. impact on monuments has been raising growing concerns. The aim of this study was to investigate Keywords Ailanthus altissima Á Biodeterioration Á the patterns of distribution and spread of invasive EU regulation on invasive alien species Á Impacts Á plants in heritage areas, taking the city of Rome as an Ornamental horticulture Á Urban flora example. We focused on woody species as they pose the greatest threat to the conservation of monuments, owing to the detrimental effects of their root system. We analysed changes in the diversity and traits of Introduction native and non-native flora growing on the walls of 26 ancient sites that have been surveyed repeatedly since Culturally protected sites, such as monumental or the 1940s. -

Ailanthus Altissima)

BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES LOWER HUDSON VALLEY PRISM HUDSONIA FOR INVASIVE PLANTS TREE-OF-HEAVEN (Ailanthus altissima) Bark of a medium-sized tree © E. Kiviat Kiviat Each leaflet has one or a few rounded teeth near its base, and a thickened, round gland on the underside of each tooth University of Tennessee Herbarium, Knoxville http://tenn.bio.utk.edu/ © E. Kiviat Kiviat A fast-growing tree to 20 m with large, odor (likened to stale peanut butter) when compound leaves composed of 10-40 leaflets. crushed. In summer and fall, large drooping Leaves and stems have a strong, unpleasant clusters of winged seeds are visible. Native to central China and Taiwan, tree-of-heaven is now invasive around the world. In the US, it became widely available to gardeners in the 1820s and is now most abundant in the East, Upper Midwest, Pacific Northwest, and California. Similar species: Several sumac (Rhus) species are most similar to tree-of-heaven. It can be distinguished from sumac as well as other trees with compound leaves by the presence of glands near the base of each leaflet. Also, tree-of-heaven has clear sap, while that of sumac is milky and sticky. Ashes (Fraxinus) have opposite leaves, and walnut and butternut (Juglans) leaflets are evenly toothed along the margins. Tree-of-heaven has a unique odor when bruised. BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR INVASIVE PLANTS -- LOWER HUDSON VALLEY PRISM -- HUDSONIA Tree-of-heaven Where found: Tree-of-heaven is shade-intolerant, and usually found in open areas with disturbed, mineral soils.1 It can grow in a wide range of soil types and conditions, and is tolerant of drought and most industrial pollutants. -

Assessing Potential Biological Control of the Invasive Plant, Tree-Of-Heaven, Ailanthus Altissima

This article was downloaded by: [USDA National Agricultural Library] On: 11 August 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 741288003] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biocontrol Science and Technology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713409232 Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima Jianqing Ding a; Yun Wu b; Hao Zheng a; Weidong Fu a; Richard Reardon b; Min Liu a a Institute of Biological Control, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, P.R. China b Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, USDA Forest Service, Morgantown, USA Online Publication Date: 01 June 2006 To cite this Article Ding, Jianqing, Wu, Yun, Zheng, Hao, Fu, Weidong, Reardon, Richard and Liu, Min(2006)'Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima',Biocontrol Science and Technology,16:6,547 — 566 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09583150500531909 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09583150500531909 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

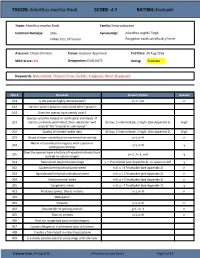

TAXON:Ailanthus Excelsa Roxb. SCORE:4.0 RATING:Evaluate

TAXON: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Evaluate Taxon: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Family: Simaroubaceae Common Name(s): ardu Synonym(s): Ailanthus wightii Tiegh. Indian tree of heaven Pongelion excelsum (Roxb.) Pierre Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 24 Aug 2016 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: EVALUATE Rating: Evaluate Keywords: Naturalized, Tropical Tree, Fodder, Coppices, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle Creation Date: 24 Aug 2016 (Ailanthus excelsa Roxb.) Page 1 of 17 TAXON: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. -

Effectiveness of Ailanthus Altissima As a Bioindicator of Ozone Pollution

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences EFFECTIVENESS OF AILANTHUS ALTISSIMA AS A BIOINDICATOR OF OZONE POLLUTION A Thesis in Ecology by Lauren K. Seiler © 2012 Lauren K. Seiler Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2012 The thesis of Lauren K Seiler was reviewed and approved* by the following: Dennis R. Decoteau Professor of Horticulture and Plant Ecosystem Health Thesis Adviser Donald D. Davis Professor of Plant Pathology Margot W. Kaye Assistant Professor of Forest Ecology David M. Eissenstat Professor of Woody Plant Physiology Chair of Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Ecology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract Ground-level ozone is one of the most significant air pollutants in the US; it is harmful to human health, vegetation, and ecosystems. Concurrently, Ailanthus altissima (tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus) is one of the most invasive plant species in the US. A series of exposure experiments and field surveys were conducted during 2010 and 2011 to evaluate the effectiveness of Ailanthus as a bioindicator of ozone pollution. To explore the uniformity of Ailanthus’ reaction to ozone, Ailanthus seedlings from 6 locations (Reno, NV; Corvallis, OR; Bloomington, IN; Mineral, VA; State College, PA; and Far Rockaway, NY) were exposed to ozone using continuously stirred tank reactor chambers within a greenhouse. Seedlings from the Corvallis, OR seed source were planted in the field and monitored for ambient ozone-induced foliar injury along with staghorn sumac, black cherry, common milkweed, and dogbane to evaluate Ailanthus’ performance compared to other ozone bioindicators. -

Harvard University's Tree Museum: the Legacy and Future of The

29 March 2017 Arboretum Wespelaar Harvard University’s Tree Museum: The Legacy and Future of the Arnold Arboretum Michael Dosmann, Ph.D. Curator of Living Collections President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives 281 Acres / 114 Hectares The Arnold Arboretum (1872) President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives Basic to applied biology of woody plants Collection based Fagus grandifolia 1800+ Uses of research in 2016 Research projects per year Practice good horticulture Training and teaching Evaluation, selection, and introduction Tilia cordata Cercidiphyllum japonicum Syringa ‘Purple Haze’ ‘Swedish Upright’ ‘Morioka Weeping’ Publication and Promotion The Backstory – why our trees have value Charles Sprague Sargent Director 1873 - 1927 Arboretum Explorer Accessioned plants 15,441 Total taxa (incl. cultivars) 3,825 Families 104 Genera 357 Species 2,130 Traditional, woody-focused collection Continental climate: -25C to 38C Collection Dynamics There is always change 121-96*C Hamamelis virginiana ‘Mohonk Red’ 1905 150 years later… 2016 Subtraction – ca 300/per year After assessment, removal of low-value material benefits high-value accessions Addition – ca 450/year Adding to the Collections Staking out new Prunus hortulana, from Missouri Planting into the Collections Net Plants – We subtract more than we add, but… when taking into account provenance, Leads to significant change in the permanent collection over time. Provenance Type 2007 2016 Wild 40% 45% Cultivated 41% 38% Uncertain 19% 17% 126-2005*C Betula lenta Plant exploration and The Arnold Arboretum Ernest Henry Wilson expeditions to East Asia • China • 1899-1902 (Veitch) • 1903-1905 (Veitch) • 1907-1909 • 1910-1911 • Japan • 1914 • Japan, Korea, Taiwan • 1917-1919 President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives Photo by EHW, 7 September 1908, Sichuan Davidia involucrata var.