1 Complexity and Ultrastructure of Infectious Extracellular Vesicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Original Article Upregulation of HOXA13 As a Potential Tumorigenesis and Progression Promoter of LUSC Based on Qrt-PCR and Bioinformatics

Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10(10):10650-10665 www.ijcep.com /ISSN:1936-2625/IJCEP0065149 Original Article Upregulation of HOXA13 as a potential tumorigenesis and progression promoter of LUSC based on qRT-PCR and bioinformatics Rui Zhang1*, Yun Deng1*, Yu Zhang1, Gao-Qiang Zhai1, Rong-Quan He2, Xiao-Hua Hu2, Dan-Ming Wei1, Zhen-Bo Feng1, Gang Chen1 Departments of 1Pathology, 2Medical Oncology, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. *Equal contributors. Received September 7, 2017; Accepted September 29, 2017; Epub October 1, 2017; Published October 15, 2017 Abstract: In this study, we investigated the levels of homeobox A13 (HOXA13) and the mechanisms underlying the co-expressed genes of HOXA13 in lung squamous cancer (LUSC), the signaling pathways in which the co-ex- pressed genes of HOXA13 are involved and their functional roles in LUSC. The clinical significance of 23 paired LUSC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues were gathered. HOXA13 levels in LUSC were detected by quantita- tive real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). HOXA13 levels in LUSC from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Oncomine were analyzed. We performed receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves of various clinicopath- ological features of LUSC. Co-expressed of HOXA13 were collected from MEM, cBioPortal and GEPIA. The func- tions and pathways of the most reliable overlapped genes were achieved from the Gene Otology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases, respectively. The protein-protein interaction (PPI) net- works were mapped using STRING. HOXA13 in LUSC were markedly upregulated compared with those in the non- cancerous controls as demonstrated by qRT-PCR (LUSC: 0.330±0.360; CONTROLS: 0.155±0.142; P=0.021). -

Supplementary Information Method CLEAR-CLIP. Mouse Keratinocytes

Supplementary Information Method CLEAR-CLIP. Mouse keratinocytes of the designated genotype were maintained in E-low calcium medium. Inducible cells were treated with 3 ug/ml final concentration doxycycline for 24 hours before performing CLEAR-CLIP. One 15cm dish of confluent cells was used per sample. Cells were washed once with cold PBS. 10mls of cold PBS was then added and cells were irradiated with 300mJ/cm2 UVC (254nM wavelength). Cells were then scraped from the plates in cold PBS and pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000g for 2 minutes. Pellets were frozen at -80oC until needed. Cells were then lysed on ice with occasional vortexing in 1ml of lysis buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100mM NaCl, 1mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing 1X protease inhibitors (Roche #88665) and RNaseOUT (Invitrogen #10777019) at 4ul/ml final concentration. Next, TurboDNase (Invitrogen #AM2238, 10U), RNase A (0.13ug) and RNase T1 (0.13U) were added and samples were incubated at 37oC for 5 minutes with occasional mixing. Samples were immediately placed on ice and then centrifuged at 16,160g at 4oC for 20 minutes to clear lysate. 25ul of Protein-G Dynabeads (Invitrogen #10004D) were used per IP. Dynabeads were pre-washed with lysis buffer and pre- incubated with 3ul of Wako Anti-Mouse-Ago2 (2D4) antibody. The dynabead/antibody mixture was added to the lysate and rocked for 2 hours at 4oC. All steps after the IP were done on bead until samples were loaded into the polyacrylamide gel. -

Palmitic Acid Effects on Hypothalamic Neurons

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.03.454666; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Running title: Oleic and palmitic acid effects on hypothalamic neurons Concentration-dependent change in hypothalamic neuronal transcriptome by the dietary fatty acids: oleic and palmitic acids Fabiola Pacheco Valencia1^, Amanda F. Marino1^, Christos Noutsos1, Kinning Poon1* 1Department of Biological Sciences, SUNY Old Westbury, Old Westbury NY, United States ^Authors contributed equally to this work *Corresponding Author: Kinning Poon 223 Store Hill Rd Old Westbury, NY 11568, USA 1-516-876-2735 [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.03.454666; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Prenatal high-fat diet exposure increases hypothalamic neurogenesis events in embryos and programs offspring to be obesity-prone. The molecular mechanism involved in these dietary effects of neurogenesis are unknown. This study investigated the effects of oleic and palmitic acids, which are abundant in a high-fat diet, on the hypothalamic neuronal transcriptome and how these changes impact neurogenesis events. The results show differential effects of low and high concentrations of oleic or palmitic acid treatment on differential gene transcription. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

G PROTEIN-COUPLED RECEPTORS Overview:- The completion of the Human Genome Project allowed the identification of a large family of proteins with a common motif of seven groups of 20-24 hydrophobic amino acids arranged as α-helices. Approximately 800 of these seven transmembrane (7TM) receptors have been identified of which over 300 are non-olfactory receptors (see Frederikson et al., 2003; Lagerstrom and Schioth, 2008). Subdivision on the basis of sequence homology allows the definition of rhodopsin, secretin, adhesion, glutamate and Frizzled receptor families. NC-IUPHAR recognizes Classes A, B, and C, which equate to the rhodopsin, secretin, and glutamate receptor families. The nomenclature of 7TM receptors is commonly used interchangeably with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), although the former nomenclature recognises signalling of 7TM receptors through pathways not involving G proteins. For example, adiponectin and membrane progestin receptors have some sequence homology to 7TM receptors but signal independently of G-proteins and appear to reside in membranes in an inverted fashion compared to conventional GPCR. Additionally, the NPR-C natriuretic peptide receptor has a single transmembrane domain structure, but appears to couple to G proteins to generate cellular responses. The 300+ non-olfactory GPCR are the targets for the majority of drugs in clinical usage (Overington et al., 2006), although only a minority of these receptors are exploited therapeutically. Signalling through GPCR is enacted by the activation of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins), made up of α, β and γ subunits, where the α and βγ subunits are responsible for signalling. The α subunit (tabulated below) allows definition of one series of signalling cascades and allows grouping of GPCRs to suggest common cellular, tissue and behavioural responses. -

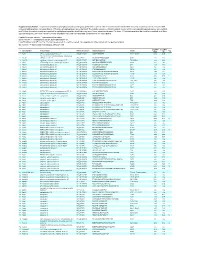

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. Large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling was performed on paired vehicle- and hormone-treated mTAL-enriched suspensions (n=3). A total of 654 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 374 unique phosphoproteins were identified. The peptide sequence, phosphorylation site(s), and the corresponding protein name, gene symbol, and RefSeq Accession number are reported for each phosphopeptide identified in any one of three experimental pairs. For those 414 phosphopeptides that could be quantified in all three experimental pairs, the mean Hormone:Vehicle abundance ratio and corresponding standard error are also reported. Peptide Sequence column: * = phosphorylated residue Site(s) column: ^ = ambiguously assigned phosphorylation site Log2(H/V) Mean and SE columns: H = hormone-treated, V = vehicle-treated, n/a = peptide not observable in all 3 experimental pairs Sig. column: * = significantly changed Log 2(H/V), p<0.05 Log (H/V) Log (H/V) # Gene Symbol Protein Name Refseq Accession Peptide Sequence Site(s) 2 2 Sig. Mean SE 1 Aak1 AP2-associated protein kinase 1 NP_001166921 VGSLT*PPSS*PK T622^, S626^ 0.24 0.95 PREDICTED: ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A 2 Abca12 (ABC1), member 12 XP_237242 GLVQVLS*FFSQVQQQR S251^ 1.24 2.13 3 Abcc10 multidrug resistance-associated protein 7 NP_001101671 LMT*ELLS*GIRVLK T464, S468 -2.68 2.48 4 Abcf1 ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 NP_001103353 QLSVPAS*DEEDEVPVPVPR S109 n/a n/a 5 Ablim1 actin-binding LIM protein 1 NP_001037859 PGSSIPGS*PGHTIYAK S51 -3.55 1.81 6 Ablim1 actin-binding -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

Transcriptional Silencing of Long Noncoding RNA GNG12-AS1 Uncouples Its Transcriptional and Product-Related Functions.” Nature Communications 7 (1): 10406

Transcriptional silencing of long noncoding RNA GNG12- AS1 uncouples its transcriptional and product-related functions The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Stojic, L., M. Niemczyk, A. Orjalo, Y. Ito, A. E. M. Ruijter, S. Uribe- Lewis, N. Joseph, et al. 2016. “Transcriptional silencing of long noncoding RNA GNG12-AS1 uncouples its transcriptional and product-related functions.” Nature Communications 7 (1): 10406. doi:10.1038/ncomms10406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10406. Published Version doi:10.1038/ncomms10406 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:26318707 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ARTICLE Received 4 Sep 2015 | Accepted 8 Dec 2015 | Published 2 Feb 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms10406 OPEN Transcriptional silencing of long noncoding RNA GNG12-AS1 uncouples its transcriptional and product-related functions Lovorka Stojic1, Malwina Niemczyk1, Arturo Orjalo2,w, Yoko Ito1, Anna Elisabeth Maria Ruijter1, Santiago Uribe-Lewis1, Nimesh Joseph1, Stephen Weston3, Suraj Menon1, Duncan T. Odom1, John Rinn4, Fanni Gergely1 & Adele Murrell1,3 Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) regulate gene expression via their RNA product or through transcriptional interference, yet a strategy to differentiate these two processes is lacking. To address this, we used multiple small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to silence GNG12-AS1,a nuclear lncRNA transcribed in an antisense orientation to the tumour-suppressor DIRAS3. -

Oligodendrocytes Remodel the Genomic Fabrics of Functional Pathways in Astrocytes

1 Article 2 Oligodendrocytes remodel the genomic fabrics of 3 functional pathways in astrocytes 4 Dumitru A Iacobas 1,2,*, Sanda Iacobas 3, Randy F Stout 4 and David C Spray 2,5 5 Supplementary Material 6 Table S1. Genes whose >1.5x absolute fold-change did not meet the individual CUT criterion. 7 Red/green background of the expression ratio indicates not significant (false) up-/down-regulation. Gene Description X CUT Acap2 ArfGAP with coiled-coil, ankyrin repeat and PH domains 2 -1.540 1.816 Adamts18 a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase -1.514 1.594 Akr1c12 aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C12 1.866 1.994 Alx3 aristaless-like homeobox 3 1.536 1.769 Alyref2 Aly/REF export factor 2 -1.880 2.208 Ankrd33b ankyrin repeat domain 33B 1.593 1.829 Ankrd45 ankyrin repeat domain 45 1.514 1.984 Ankrd50 ankyrin repeat domain 50 1.628 1.832 Ankrd61 ankyrin repeat domain 61 1.645 1.802 Arid1a AT rich interactive domain 1A -1.668 2.066 Artn artemin 1.524 1.732 Aspm abnormal spindle microtubule assembly -1.693 1.716 Atp6v1e1 ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit E1 -1.679 1.777 Bag4 BCL2-associated athanogene 4 1.723 1.914 Birc3 baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3 -1.588 1.722 Ccdc104 coiled-coil domain containing 104 -1.819 2.130 Ccl2 chemokine -1.699 2.034 Cdc20b cell division cycle 20 homolog B 1.512 1.605 Cenpf centromere protein F 2.041 2.128 Cep97 centrosomal protein 97 -1.641 1.723 COX1 mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I -1.607 1.650 Cpsf7 cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 7 -1.635 1.891 Crct1 cysteine-rich -

List of Predicted Circfam120a Target Mrnas Gene in Pathway Species Gene Name

List of predicted circFAM120A target mRNAs Gene in pathway Species Gene name HRAS Homo sapiens HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase (HRAS) ADCY1 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 1 (ADCY1) ADCY2 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 2 (ADCY2) ADCY7 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 7 (ADCY7) PTGS2 Homo sapiens Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) PGF Homo sapiens Placental growth factor (PGF) ADCY5 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 5 (ADCY5) STAT5A Homo sapiens Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A (STAT5A) ADCY6 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 6 (ADCY6) STAT5B Homo sapiens Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B (STAT5B) LPAR3 Homo sapiens Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 3 (LPAR3) LPAR2 Homo sapiens Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 2 (LPAR2) CTNNB1 Homo sapiens Catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) CUL2 Homo sapiens Cullin 2 (CUL2) RARA Homo sapiens Retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA) GNG2 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 2 (GNG2) RARB Homo sapiens Retinoic acid receptor beta (RARB) GNG3 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 3 (GNG3) FAS Homo sapiens Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS) GNG4 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 4 (GNG4) GNG7 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 7 (GNG7) PIK3CG Homo sapiens Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma (PIK3CG) WNT10B Homo sapiens Wnt family member 10B (WNT10B) BCR Homo sapiens BCR, RhoGEF and GTPase activating protein (BCR) BRAF Homo sapiens B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) RXRB Homo sapiens Retinoid X receptor beta (RXRB) ROCK2 Homo sapiens Rho -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Identification of a Multisubunit E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Required for Heterotrimeric G-Protein

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Identification of a multisubunit E3 ubiquitin ligase required for heterotrimeric G-protein beta-subunit ubiquitination and cAMP signaling A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular Biology by Brian Daniel Young 2018 © Copyright by Brian Daniel Young 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Identification of a multisubunit E3 ubiquitin ligase required for heterotrimeric G-protein beta-subunit ubiquitination and cAMP signaling by Brian Daniel Young Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular Biology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor James Akira Wohlschlegel, Chair GPCRs are stimulated by extracellular ligands and initiate a range of intracellular signaling events through heterotrimeric G-proteins. Upon activation, G-protein α- subunits (Gα) and the stable βγ-subunit dimer (Gβγ) bind and alter the activity of diverse effectors. These signaling events are fundamental and subject to multiple layers of regulation. In this study, we used an unbiased proteomic mass spectrometry approach to uncover novel regulators of Gβγ. We identified a subfamily of potassium channel tetramerization domain (KCTD) proteins that specifically bind Gβγ. Several KCTD proteins are substrate adaptor proteins for CUL3–RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. Our studies revealed that a KCTD2-KCTD5 hetero-oligomer associates with CUL3 through KCTD5 subunits and recruits Gβγ through both subunits. Using in vitro ubiquitination reactions, we demonstrated that these KCTD proteins promote monoubiquitination of lysine-23 within Gβ1/2. This ubiquitin modification of Gβ1/2 is also observed in human ii cells and is dependent on these substrate adaptor proteins. Because these KCTD proteins bind Gβγ in response to G-protein activation, we investigated their role in GPCR signaling. -

Planell N Et Al. Supplementary Material Supplementary Table 2. Biological Pathways Analysis by IPA. Pathway Analysis Was Perform

Planell N et al. Supplementary Material Supplementary Table 2. Biological pathways analysis by IPA. Pathway analysis was performed for those genes significantly perturbed in affected colonic biopsies from UC active and UC-in-remission samples compared to non-IBD controls (Supplementary Table 2A) or in UC active involved compared to non-IBD controls (Supplementary Table 2B), using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity™ Systems, www.ingenuity.com). In bold are shown those genes that were included in the real-time RT-PCR validation set. Supplementary Table 2A. Main biological functions significantly perturbed in deregulated genes in both active and inactive UC versus non-IBD controls (patterns 2 and 3 of gene expression, Figure 2). Biological functions Genes Cell communication: SERPINB5, SLC4A2, TGFB1, TGFBI, VCAM1, attachment of cells, DSG2, ICAM2, ITGA2, ITGA6, PTEN, PTGER2, cell-cell contact, disassembly of focal adhesions, TFPI2, TGFA, TGM2, VCAN, DSP, JAM2, JAM3, adhesion of connective GJA1, OCLN, PARD3, TJP1, TJP3 tissue cells, formation of tight junctions Cell death: FAS, FOXO3, GATA6, HGF, ITSN1, KLF5, LUM, cell death of epithelial cell lines, MAP3K5, MAPK14, PARP1, SERPINA1, cytotoxicity of tumor cell lines, apoptosis of endothelial cells, SERPINB5, TGFB1, THBS1, TLR3, TNFRSF10A, apoptosis of vascular TNFRSF10B, TNFRSF11B, TNFSF10, ABCG2, JUN, endothelial cells, apoptosis of microvascular MAP2K6, MET, PEA15, TCF3, TCF4, TGFA, endothelial cells TGFB1I1, TICAM1, TICAM2, TNFRSF1B, TRIM27, SMAD7, TGFBR2 ABCD3, AKAP1, AKAP2/PALM2-AKAP2, -

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Exome Sequencing Reveals Heterogeneous Clonal Dynamics in Donor Cell Myeloid Neoplasms After Stem Cell Transplantation

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Exome sequencing reveals heterogeneous clonal dynamics in donor cell myeloid neoplasms after stem cell transplantation Julia Suárez-González, 1,2 Juan Carlos Triviño, 3 Guiomar Bautista, 4 José Antonio García-Marco, 4 Ángela Figuera, 5 Antonio Balas, 6 José Luis Vicario, 6 Francisco José Ortuño, 7 Raúl Teruel, 7 José María Álamo, 8 Diego Carbonell, 2,9 Cristina Andrés-Zayas, 1,2 Nieves Dorado, 2,9 Gabriela Rodríguez-Macías, 9 Mi Kwon, 2,9 José Luis Díez-Martín, 2,9,10 Carolina Martínez-Laperche 2,9* and Ismael Buño 1,2,9,11* on behalf of the Spanish Group for Hematopoietic Transplantation (GETH) 1Genomics Unit, Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital, Gregorio Marañón Health Research Institute (IiSGM), Madrid; 2Gregorio Marañón Health Research Institute (IiSGM), Madrid; 3Sistemas Genómicos, Valencia; 4Department of Hematology, Puerta de Hierro General University Hospital, Madrid; 5Department of Hematology, La Princesa University Hospital, Madrid; 6Department of Histocompatibility, Madrid Blood Centre, Madrid; 7Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology Unit, IMIB-Arrixaca, Morales Meseguer General University Hospital, Murcia; 8Centro Inmunológico de Alicante - CIALAB, Alicante; 9Department of Hematology, Gregorio Marañón General University Hospital, Madrid; 10 Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Com - plutense University of Madrid, Madrid and 11 Department of Cell Biology, School of Medicine, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain *CM-L and IB contributed equally as co-senior authors. Correspondence: