P0093-P0103.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juices Beverages Sweets Breakfast Toasts

BREAKFAST SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE VG CHIA CHARGE $100 Gluten-Free Overnight Oats, Chia Seeds, CATERING MENU Old Chatham Sheep’s Milk Yogurt, HB Raw Wildflower Honey, Blueberry Compote, Banana, HB Granola VG EGG SANDWICH $100 ON 8 GRAIN BREAD Two Over Easy Omega 3 Eggs, HB Honey “Sriracha,” Arugula, 8 Grain Ciabatta CHOOSE ONE: Plainville Farms Turkey Bacon or Mashed Avocado VG QUINOA RANCHERO $110 BEVERAGES POWER BOWL SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE Two 8 Minute Omega 3 Eggs, Black Beans, Tri-Color Quinoa, Himalayan Ruby Rice, Roasted Corn, Mango, Jicama Salad, LA COLOMBE COFFEE $30 Seeded Corn Tortilla Crisp V SEASONAL FRUIT SALAD $100 ASSORTED TEAS $30 VG ASSORTED GLUTEN FREE $80 STILL OR SPARKLING WATER $25 BREAKFAST PASTRIES Vegan Options Available FRUIT-INFUSED ICED TEAS $45 Ginger Mango Peach or Pear Green VG MULTI-GRAIN CHIA SEED $50 CROISSANTS GREEN TEA REFRESH $45 Matcha, Peppermint Lime Tea, Cucumber email: [email protected] TOASTS BELGIAN HOT CHOCOLATE $40 @honeybrainslife SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE 80% Dark Belgian Chocolate, Raw Wildflower Honey, Choice of Milk V AVOCADO TOAST $110 Crushed Avocado, Lemon, Chia Hemp Flax Seed Medley, Maldon Salt, Infused JUICES Olive Oil, Seeded Sourdough SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE SMOKED SALMON TOAST $130 FRESHLY SQUEEZED $25 Atlantic Salmon, Labneh Spread, ORANGE JUICE Cucumber, Fresh Dill, Extra Virgin Olive Oil, Lemon Zest, Sourdough ASSORTED HB $90 COLD PRESSED JUICES VG DARK CHOCOLATE $110 GANACHE PRALINE TOAST ASSORTED HB JUICE SHOTS $35 Toasted Pecan Pralines in Molasses, Banana, HB Raw Wildflower -

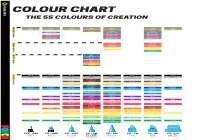

Colour Chart

posca.com COLOUR CHART THE 55 COLOURS OF CREATION Metallic colours Metallic Gold Gold Gold Gold Gold Gold Gold Silver Silver Silver Silver Silver Silver Silver Bronze Bronze Bronze Metallic blue Metallic blue Metallic blue Metallic violet Metallic violet Metallic pink Metallic pink Metallic pink Metallic red Metallic red Metallic red Metallic green Metallic green Metallic green Fluoro colours Fluoro Fluo pink Fluo pink Red fluo Red fluo Fluo orange Fluo orange Fluo light orange Yellow fluo Yellow fluo Green fluo Glitter colours Glitter Blue Light blue Violet Pink Red Orange Yellow Green Classic colours Classic Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black White White White White White White White White Grey Grey Grey Grey Grey Dark brown Brown Brown Brown Brown Brown Ivory Ivory Ivory Ivory Beige Beige Beige Beige Navy blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Turquoise Sky blue Sky blue Slate grey Slate grey Slate grey Slate grey Lilac Lilac Violet Violet Violet Violet Violet Violet Fuchsia Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Corail pink Light pink Light pink Light pink Red Red Red Red Red Red Red Red Dark red Red wine Red wine Red wine Red wine Orange Orange Orange Orange Orange Orange Bright yellow Bright yellow Bright yellow Bright yellow Light orange Light orange Light orange Light orange Light orange Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Straw yellow Straw yellow Straw yellow Apple green Apple green Light green Light green Light green Light green Light green Aqua green Green Green Green Green Green Green Green Green Emerald green Emerald green Khaki green PCF - 350 PC - 1MR PC - 1MC PC - 3M PC - 5M PC - 7M PC - 8K PC - 17K 1-10 mm 0,7 mm 0,7-1 mm 1,8-2,5 mm 4,5-5,5 mm 8 mm 15 mm PC - 3ML Bold Extra bold Brush Ultra fine Extra fine 0,9-1,3 mm Medium Bold Fine. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

Chalet Nursery Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax

Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax Phormium tenax 'Apricot Queen' Height: 4 feet Spread: 5 feet Spacing: 4 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: (annual) Description: A stunning perennial that has large sword-like leaves that emerge apricot and mature to light yellow with a green margin; beautiful and eye catching as an accent in the garden or massed along borders; also a great center for a Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax mixed container foliage Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder Ornamental Features Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax's attractive large sword-like leaves emerge peach in spring, turning buttery yellow in color with distinctive green edges the rest of the year. Neither the flowers nor the fruit are ornamentally significant. Landscape Attributes Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax is an open herbaceous annual with a more or less rounded form. Its relatively coarse texture can be used to stand it apart from other garden plants with finer foliage. This is a relatively low maintenance plant, and is best Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax cleaned up in early spring before it resumes active growth Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder for the season. Deer don't particularly care for this plant and will usually leave it alone in favor of tastier treats. It has no significant negative characteristics. Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax is recommended for the following landscape applications; - Accent - Mass Planting - General Garden Use - Container Planting 3132 LAKE AVENUE W ILM ETTE, ILLINOIS 60091 847.256.0561 W W W.CHALETNURSERY.COM Planting & Growing Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax will grow to be about 4 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 5 feet. -

70 SOLID COLORS for All Rubber Tile and Tread Profiles (Excluding Smooth and Hammered R24); Rubber and Vinyl Wall Base; and Rubber Accessories)

70 SOLID COLORS For all rubber tile and tread profiles (excluding Smooth and Hammered R24); rubber and vinyl wall base; and rubber accessories) Q 100 177 Q 150 Q 193 Q 123 Q 114 Q 129 Q 178 black steel blue dark gray black brown charcoal lunar dust dolphin pewter Q 194 148 Q 175 Q 174 197 Q 110 burnt umber steel gray slate smoke iceberg brown Q 147 Q 182 Q 623 Q 624 Q 140 Q 191 Q 125 171 light brown toffee nutmeg chameleon fawn camel fig sandstone Q 130 Q 198 Q 632 Q 184 Q 170 Q 131 127 Q 631 buckskin ivory flax almond white bisque harvest yellow sahara Q 639 640 Q 122 Q 195 663 648 647 646 beigewood creekbed natural light gray aged fern pear green spring dill gecko 160 649 169 662 118 187 139 627 forest green sweet basil hunter green envy peacock blue deep navy mariner 618 665 664 656 654 638 637 655 aubergine horizon blue jay bluebell lagoon cadet night mist peaceful blue 657 658 621 659 186 137 188 617 sorbet berry ice merlin grape red cinnabar brick terracotta 660 661 643 644 642 645 Q 641 Q 161 citrus marmalade mimosa sunbeam jonquil blonde moonrise snow MARBLEIZED COLORS For all rubber tile and tread profiles (excluding Hammered R24). M100 M177 M150 M193 M123 M114 M129 M178 black steel blue dark gray black brown charcoal lunar dust dolphin pewter M194 M148 M175 M174 M197 M110 burnt umber steel gray slate smoke iceberg brown M147 M182 M623 M624 M140 M191 M125 M171 light brown toffee nutmeg chameleon fawn camel fig sandstone M130 M198 M632 M184 M170 M131 M127 M631 buckskin ivory flax almond white bisque harvest yellow sahara M639 M640 -

2014 Price Guide

2014 PRICE GUIDE BEAUTY CRAFTSMANSHIP DESIGN THE CAMBRAI COLLECTION TAKES ITS NAME FROM THE ANCIENT TOWN IN FRANCE, WHICH GREW TO PROMINENCE IN THE MIDDLE AGES AS THE CENTER OF LINEN PROCESSING AND WEAVING. FLAX FROM ALL OVER THE KNOWN WORLD WAS BROUGHT TO CAMBRAI AND TURNED INTO LINEN FABRICS, WHICH WERE PRIZED FOR THEIR COMBINATION OF SOFTNESS AND STRENGTH. IT IS THIS COMBINATION OF PROPERTIES THAT LED TO THE CHOICE OF FLAX AS A BASE MATERIAL FOR THIS EXCLUSIVE NEW COLLECTION OF SHADE MATERIALS. THESE PATTERNS INTERWEAVE FLAX WITH DECORATIVE ELEMENTS OF BAMBOO, JUTE, REEDS, HEMP AND COTTON SLUB YARNS TO CREATE A STUNNING RANGE OF DESIGNS. THE RESULT IS A COLLECTION OF SOFT, LIGHT FABRICS, WHICH ARE ALSO TOUGH AND DURABLE ENOUGH TO WITHSTAND YEARS OF SERVICE—SOMETHING NEW AND UNIQUE IN WINDOW TREATMENTS. PLEASE READ THIS GUIDE CAREFULLY TO UNDERSTAND HOW BEST TO SPECIFY AND ORDER YOUR SHADES AND HOW TO TAKE CARE OF THEM. 2 MATERIALS REFERENCE PRICE FABRIC MAX WIDTH FABRIC STANDARD STANDARD PATTERN # PATTERN NAME GROUP COMPOSITION WIDTH w/CORD LOCK WEIGHT (g/m2) EB COLOR LINER COLOR Privacy Blackout ZH-148 ARUNDO DUSK A 90% Flax, 10% Reed 96" 60" 270 SILVER GRAY GRAY DARK LINEN ZH-152 ARUNDO ECRU A 90% Flax, 5% Reed, 5% Jute 96" 60" 210 IVORY/MARBLE NATURAL SOFT WHITE ZH-212 ARUNDO STONE A 90% Flax, 5% Reed, 5% Jute 96" 60" 300 SILVER GRAY GRAY DARK LINEN ZH-147 ARUNDO SUNSET A 90% Flax, 10% Reed 96" 60" 270 DARK TAUPE GRAY DARK LINEN ZH-199 BATISTE DARK* B 95% Flax, 5% Bamboo 96" 50" 250 DARK TAUPE GRAY DARK LINEN ZH-200 BATISTE LIGHT* -

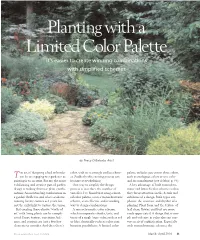

Planting with a Limited Color Palette It’S Easier to Create Winning Combinations with Simplified Schemes

Planting with a Limited Color Palette It’s easier to create winning combinations with simplified schemes by Tracy DiSabato-Aust HE art of designing a bed or border color, with its seemingly endless choic- palette includes just two or three colors, T can be as engaging to a gardener as es. Suddenly this exciting process can such as analogous colors or one color painting is to an artist. For me, the most become overwhelming. and its complement (see sidebar, p. 44). exhilarating and creative part of garden One way to simplify the design A key advantage of both monochro- design is making dramatic plant combi- process is to reduce the number of matic and limited color schemes is that nations. An outstanding combination in variables. I’ve found that using a limit- they focus attention on the details and a garden thrills me and often sends me ed color palette, even a monochromatic subtleties of a design. Both types em- running for my camera as I yearn for scheme, is an effective and rewarding phasize the structure and rhythm of a just the right light to capture the vision. way to design combinations. planting. Plant form and the texture of But creating these elusive “works of A monochromatic color scheme, leaf, stem, flower, and fruit are more art” with living plants can be compli- which incorporates shades, tints, and easily appreciated. A design that is sim- cated. Form, texture, repetition, bal- tones of a single basic color, such as red ple and cohesive in color also can con- ance, and contrast are just a few key or blue, drastically reduces color com- vey an air of sophistication. -

FB Spice Savvy

EXPERT TIPS & INFORMATION GIving back ON USING BULK INGREDIENTS ABOUT CHIA SEED Chia seed (Salvia hispanica), sometimes simply called “chia,” is a desert plant native to central and southern Mexico and Guatemala. The tiny black and white seeds were grown by the Aztecs in the 14th century. Today chia is cultivated primarily in South America, western Mexico and the southwestern United States. The seed is often used as a topping on foods or, like fl axseed, mixed by the spoonful into everyday cereals, breads, yogurts and smoothies. Chia seeds are a common ingredient in granola bars and energy bars, thanks to their pleasing nutty fl avor. For vegans and others avoiding eggs, chia seed is often used as an egg substitute. For the equivalent of one egg, combine 1 tablespoon of ground seed with 3 tablespoons of water. The resulting gelatinous substance can then be used in baking bulks av v y and cooking to provide the binding properties of an egg. (This technique works — in the same ratio — with fl axseed too.) We’re committed to providing sustainably sourced bulk products Versatile chia seed has a lot more to offer than the amusement to our customers — products sourced with respect for the of a chia pet — it’s a super seed you can work into your daily environment and the people around the world who produce them. diet with little effort and big benefi ts. (It’s also delicious — try our We deal ethically with our growers and their communities and Lemon Raspberry Chia Seed Pudding recipe inside for a delightful work with them to preserve and protect their resources. -

Discrimination of Flax Cultivars Based on Visible Diffusion Reflectance Spectra and Colour Parameters of Whole Seeds

Czech Journal of Food Sciences, 37, 2019 (3): 199–204 Food Analysis, Food Quality and Nutrition https://doi.org/10.17221/202/2018-CJFS Discrimination of flax cultivars based on visible diffusion reflectance spectra and colour parameters of whole seeds Yana Troshchynska1*, Roman Bleha2, Lenka Kumbarová2, Marcela Sluková2, Andrej Sinica2, Jiří Štětina1 1Department of Dairy, Fat and Cosmetics, Faculty of Food and Biochemical Technology, University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic 2Department of Carbohydrates and Cereals, Faculty of Food and Biochemical Technology, University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Troshchynska Y., Blecha R., Kumbarová L., Sluková M., Sinica A., Štětina J. (2019): Discrimination of flax cultivars based on visible diffusion reflectance spectra and colour parameters of whole seeds. Czech J. Food Sci., 37: 199–204. Abstract: Discrimination of yellow and brown seeded flax cultivars was made based on visible (Vis) diffusion -re flectance spectra of whole seeds. Hierarchy cluster analysis (HCA) and principal component analysis (PCA) were used for the discrimination. Multivariate analyses of Vis spectra led to satisfactory discrimination of all flax cultivars of this study. The CIE L*a*b* colour parameters were calculated from the diffusion reflectance Vis spectra. The values of L* were in the range of 48.8–53.6 and 62.6–66.0% for brown and yellow seeded cultivars, respectively. Chromatic parameters a* and b* were in the range of 2.8–4.9 and 7.9–16.4%, respectively. A strong linear correlation (R2 = 0.9712) was found between a* and b* parameters for all the flaxseed samples. -

Blueberry Flax Lily Dianella Tasmanica ‘Variegata’

Blueberry Flax Lily dianella tasmanica ‘Variegata’ This Florida-Friendly plant is well known for its variegated color and its arching, strap-like foliage. Its foliage is showy with dark green color and contrasting ivory stripes. In the late spring and summer, the plant yields branched stems above the foliage that flower with very small, star-shaped flowers with yellow anthers in the center. These inconspicuous flowers are followed by a more visible, non-edible berry-like fruit that will remain on the plant for while and from which the plant receives its ‘blueberry’ name. The Blueberry Flax Lily is a low vertical-growing perennial ground cover that is native to Australia and can be found in warm climates across the United States, particularly in coastal areas. Indeed, it is a salt tolerant plant and is capable of enduring heat and humidity, but it also does well in the shade. It is susceptible to freeze damage, but normally recovers fine once warmer temperatures set in. It is considered a Florida-Friendly plant needing less water, having fewer pest problems and performing better under water stress then most other types of border grasses. Blueberry Flax Lily potted Blueberry Flax Lily leaves Blueberry Flax Lily flowers (352) 429 - 2171 / 7836 Cherry Lake Road, Groveland FL, 34736 / cherrylake.com Blueberry Flax Lily dianella tasmanica ‘Variegata’ Common Names: Native Origin : Tasman Flax Lily, Southeastern Australia Variegated Flax Lily and Tasmania Environment: Description: Soil: clay, loam, sand Hardy Range: 8 – 11 Salt: moderate Mature Height: 2 – 3’ Exposure: full sun to Mature Spread: 2 – 3’ partial shade Growth Rate: moderate Growth Habit: clumping Ornamental Characteristics: Foliage is dark green with ivory stripes. -

APRIL, 1949 the American Horticultural Society PRESENT ROLL of OFFICERS and DIRECTORS April, 1949

The NATIONAL HORTICULTURAL MAGAZINE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL 80cmTY APRIL, 1949 The American Horticultural Society PRESENT ROLL OF OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS April, 1949 OFFICERS President, Mr. H. E. Allanson, Port Republic, Md. First Vice-President, Mr. Frederic P. Lee, Bethesda, Md. Second Vice-President, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Washington. D. C. Secretary, Dr. Conrad B. Link, College Park, Md. Treasurer, Mr. Carl O. Erlanson, Silver Spring, Md. Editor, Mr. B. Y. Morrison, Takoma Park, Md. DIRECTORS L' Terms expiring 1949 Terms expiring 1950 Mrs. Robert Fife, New York, N. Y. Mrs. Walter Douglas, Chauncey, N. Y. Mrs. Mortimer J. Fox, Peekskill, N. Y. Mrs. J. Norman Henry, Gladwyne, Pa. Dr. David V. Lumsden, North Chevy Chase, Mrs. Arthur Hoyt Scott. Media, Pa. Md. Dr. Freeman Weiss, Washington, D. C. Dr. Vernon T. Stoutemyer, Los Angeles, Calif. Dr. Donald Wyman, Jamaica Plain, Mass. HONORARY---- VICE-PRESIDENTS Mrs. Mary Hazel Drummond, Pres., Mr. Allen W. Davis, Pres., American Begonia Society, American Primrose Society, 1246 No. Kings Road, 3424 S. W. Hurne St., Los Angeles 46, Calif. Portland I, Ore. Dr. H. Harold Hume, .Pres., Mr. Harold Epstein, Pres., . American Camellia Society, '. American 'Rock Garden Society, University of Florida, 5 For~st Court, Gainesville, Fla. Larchmont, N. Y. Mr. Carl Grant Wilson, Pres., Mr. John Henny, Jr., Pres., American Defphipium. Society, American ,Rhododendron Society, 22150 Euclid Ave., Brooks,' Oregon ·Mr. George A. Sweetser, Pres., Cleveland, Ohio American Rose Society, Dr. Frederick L. Fagley, PrOl., 36 Forest St., American Fern Society, Wellesley Hills, Mass. W Fourth Ave., Mr. Wm. T. Marshall, Pres. Emeritus, New York 10, N. -

Blue and Lewis Flax

Plant Guide forage value. Birds use the seed and capsules in fall BLUE FLAX and winter. All species provide diversity to the seeded plant community. Linum perenne L. plant symbol = LIPE2 Erosion control/reclamation/greenstripping: All flax species are noted for their value in mixes for erosion control and beautification values. The six week LEWIS FLAX flowering period and showy blue flowers make seedings more aesthetically pleasing and increase Linum lewisii Pursh plant biodiversity. Due to the semi-evergreen nature plant symbol = LILE3 of the species, flax can also be used as a fire suppressant species in green strip plantings. Contributed By: USDA, NRCS, Idaho State Office & National Plant Data Center Wildlife: Flax is considered desirable forage for deer, antelope, and birds, either as herbage or seed. They may also provide some cover for selected small bird species. Status Consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status, such as, state noxious status and wetland indicator values. Description General: Flax Family (Linaceae). Linum perenne is introduced from Eurasia. Linum lewisii is a comparable U.S. native plant (figure 1). In general, flax is an annual or short-lived, semi-evergreen perennial forb, sometimes semi-woody at base with attractive flowers ranging from white to blue to yellow to red in color. The flax species with yellow to red flowers can be toxic to livestock. Common in the western United States, blue flax is considered a woody sub-shrub in the PLANTS database (USDA, NRCS 2000). According to Cronquist et al. (1997), “the only significant difference between Linum lewisii and the Eurasian Linum perenne appears to be that the former is homostylic, and the latter Alternate Names heterostylic.” Prairie flax Flax plants have many narrow, small, alternate Uses (rarely opposite), simple and entire leaves that are Ethnobotanic: Cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum) sessile (lacking stalks) on the stems.