Thomson, Christine, "Last but Not Least" Examination And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garcinia Hanburyi Guttiferae Hook.F

Garcinia hanburyi Hook.f. Guttiferae LOCAL NAMES English (gamboge tree); German (Gutti,Gummigutt); Thai (rong); Vietnamese (dang hoang) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION An evergreen, small to medium-sized tree, up to 15 m tall, with short and straight trunk, up to 20 cm in diameter; bark grey, smooth, 4-6 mm thick, exuding a yellow gum-resin. Leaves opposite, leathery, elliptic or ovate-lanceolate, 10-25 cm x 3-10 cm, cuneate at base, acuminate at apex, shortly stalked. Flowers in clusters or solitary in the axils of fallen leaves, 4-merous, pale yellow and fragrant, unisexual or bisexual; male flowers somewhat smaller than female and bisexuals; sepals leathery, orbicular, 4-6 mm long, persistent; petals ovate, 6-7 mm long; stamens numerous and arranged on an elevated receptacle in male flowers, less numerous and reduced in female flowers; ovary superior, 4-loculed, with sessile stigma. Fruit a globose berry, 2-3 cm in diameter, smooth, with recurved sepals at the base and crowned by the persistent stigma, 1-4 seeded. Seeds 15-20 mm long, surrounded by a pulpy aril. The gum-resin from G. hanburyi is often called Siamese gamboge to distinguish it from the similar product from the bark of G. morella Desr., called Indian gamboge. The species are closely related, and G. hanburyi has been considered in the past as a variety of G. morella. BIOLOGY Normally it flowers in November and December and fruits from February to April. Agroforestry Database 4.0 (Orwa et al.2009) Page 1 of 5 Garcinia hanburyi Hook.f. Guttiferae ECOLOGY Gamboge tree occurs naturally in rain forest. -

Historical Uses of Saffron: Identifying Potential New Avenues for Modern Research

id8484906 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ISSN : 0974 - 7508 Volume 7 Issue 4 NNaattuurraall PPrrAoon dIdnduuian ccJotutrnssal Trade Science Inc. Full Paper NPAIJ, 7(4), 2011 [174-180] Historical uses of saffron: Identifying potential new avenues for modern research S.Zeinab Mousavi1, S.Zahra Bathaie2* 1Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, (IRAN) 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, (IRAN) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 20th June, 2011 ; Accepted: 20th July, 2011 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Background: During the ancient times, saffron (Crocus sativus L.) had Saffron; many uses around the world; however, some of them were forgotten Iran; ’s uses came back into attention during throughout the history. But saffron Ancient medicine; the past few decades, when a new interest in natural active compounds Herbal medicine; arose. It is supposed that understanding different uses of saffron in past Traditional medicine. can help us in finding the best uses for today. Objective: Our objective was to review different uses of saffron throughout the history among different nations. Results: Saffron has been known since more than 3000 years ago by many nations. It was valued not only as a culinary condiment, but also as a dye, perfume and as a medicinal herb. Its medicinal uses ranged from eye problems to genitourinary and many other diseases in various cul- tures. It was also used as a tonic agent and antidepressant drug among many nations. Conclusion(s): Saffron has had many different uses such as being used as a food additive along with being a palliative agent for many human diseases. -

Juices Beverages Sweets Breakfast Toasts

BREAKFAST SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE VG CHIA CHARGE $100 Gluten-Free Overnight Oats, Chia Seeds, CATERING MENU Old Chatham Sheep’s Milk Yogurt, HB Raw Wildflower Honey, Blueberry Compote, Banana, HB Granola VG EGG SANDWICH $100 ON 8 GRAIN BREAD Two Over Easy Omega 3 Eggs, HB Honey “Sriracha,” Arugula, 8 Grain Ciabatta CHOOSE ONE: Plainville Farms Turkey Bacon or Mashed Avocado VG QUINOA RANCHERO $110 BEVERAGES POWER BOWL SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE Two 8 Minute Omega 3 Eggs, Black Beans, Tri-Color Quinoa, Himalayan Ruby Rice, Roasted Corn, Mango, Jicama Salad, LA COLOMBE COFFEE $30 Seeded Corn Tortilla Crisp V SEASONAL FRUIT SALAD $100 ASSORTED TEAS $30 VG ASSORTED GLUTEN FREE $80 STILL OR SPARKLING WATER $25 BREAKFAST PASTRIES Vegan Options Available FRUIT-INFUSED ICED TEAS $45 Ginger Mango Peach or Pear Green VG MULTI-GRAIN CHIA SEED $50 CROISSANTS GREEN TEA REFRESH $45 Matcha, Peppermint Lime Tea, Cucumber email: [email protected] TOASTS BELGIAN HOT CHOCOLATE $40 @honeybrainslife SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE 80% Dark Belgian Chocolate, Raw Wildflower Honey, Choice of Milk V AVOCADO TOAST $110 Crushed Avocado, Lemon, Chia Hemp Flax Seed Medley, Maldon Salt, Infused JUICES Olive Oil, Seeded Sourdough SERVES UP TO 10 PEOPLE SMOKED SALMON TOAST $130 FRESHLY SQUEEZED $25 Atlantic Salmon, Labneh Spread, ORANGE JUICE Cucumber, Fresh Dill, Extra Virgin Olive Oil, Lemon Zest, Sourdough ASSORTED HB $90 COLD PRESSED JUICES VG DARK CHOCOLATE $110 GANACHE PRALINE TOAST ASSORTED HB JUICE SHOTS $35 Toasted Pecan Pralines in Molasses, Banana, HB Raw Wildflower -

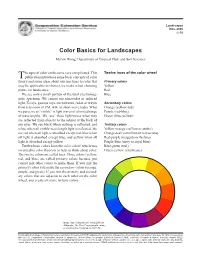

Color Basics for Landscapes

Landscapae Nov. 2006 L-18 Color Basics for Landscapes Melvin Wong, Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences he topic of color can become very complicated. This Twelve hues of the color wheel Tpublication introduces some basic concepts of color theory and some ideas about our reactions to color that Primary colors may be applicable to choices we make when choosing Yellow plants for landscapes. Red We see only a small portion of the total electromag Blue netic spectrum. We cannot see ultraviolet or infrared light, X-rays, gamma rays, microwaves, radar, or waves Secondary colors from television or FM, AM, or short-wave radio. What Orange (yellow-red) we perceive as “visible” is light waves of a limited range Purple (red-blue) of wavelengths. We “see” these light waves when they Green (blue-yellow) are reflected from objects to the retinas at the back of our eyes. We see black when nothing is reflected, and Tertiary colors white when all visible-wavelength light is reflected. We Yellow-orange (saffron or amber) see red when all light is absorbed except red, blue when Orange-red (vermillion or terra-cotta) all light is absorbed except blue, and yellow when all Red-purple (magenta or fuchsia) light is absorbed except yellow. Purple-blue (navy or royal blue) Twelve basic colors form the color wheel, which was Blue-green (teal) invented by color theorists to help us think about color. Green-yellow (chartreuse) The twelve colors are called hues. Three colors (yellow, red, and blue) are called primary colors because you cannot mix other colors to make them. -

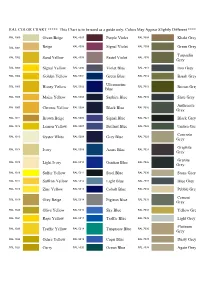

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

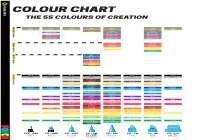

Colour Chart

posca.com COLOUR CHART THE 55 COLOURS OF CREATION Metallic colours Metallic Gold Gold Gold Gold Gold Gold Gold Silver Silver Silver Silver Silver Silver Silver Bronze Bronze Bronze Metallic blue Metallic blue Metallic blue Metallic violet Metallic violet Metallic pink Metallic pink Metallic pink Metallic red Metallic red Metallic red Metallic green Metallic green Metallic green Fluoro colours Fluoro Fluo pink Fluo pink Red fluo Red fluo Fluo orange Fluo orange Fluo light orange Yellow fluo Yellow fluo Green fluo Glitter colours Glitter Blue Light blue Violet Pink Red Orange Yellow Green Classic colours Classic Black Black Black Black Black Black Black Black White White White White White White White White Grey Grey Grey Grey Grey Dark brown Brown Brown Brown Brown Brown Ivory Ivory Ivory Ivory Beige Beige Beige Beige Navy blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Dark blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Light blue Turquoise Sky blue Sky blue Slate grey Slate grey Slate grey Slate grey Lilac Lilac Violet Violet Violet Violet Violet Violet Fuchsia Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Pink Corail pink Light pink Light pink Light pink Red Red Red Red Red Red Red Red Dark red Red wine Red wine Red wine Red wine Orange Orange Orange Orange Orange Orange Bright yellow Bright yellow Bright yellow Bright yellow Light orange Light orange Light orange Light orange Light orange Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Yellow Straw yellow Straw yellow Straw yellow Apple green Apple green Light green Light green Light green Light green Light green Aqua green Green Green Green Green Green Green Green Green Emerald green Emerald green Khaki green PCF - 350 PC - 1MR PC - 1MC PC - 3M PC - 5M PC - 7M PC - 8K PC - 17K 1-10 mm 0,7 mm 0,7-1 mm 1,8-2,5 mm 4,5-5,5 mm 8 mm 15 mm PC - 3ML Bold Extra bold Brush Ultra fine Extra fine 0,9-1,3 mm Medium Bold Fine. -

Color Coat Mixing System

SSTCL 03/09 ® SPECIALS COLOR COAT MIXING SYSTEM FOREIGN CARS MUSTANG THUNDERBIRD CORVETTE FOR TECHNICAL INFORMATION CALL 800-831-1122 SEM PRODUCTS, INC. - 1685 Overview Drive - Rock Hill, SC 29730 www.semproducts.com SPECIALS ® SSTCL COLOR COAT MIXING SYSTEM 03/09 FOREIGN CARS, THUNDERBIRD, MUSTANG AND CORVETTE COLORS ACURA CORVETTE Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. N/A BLUE 88-89 4554 N/A AQUA 59 4892 N/A CHARCOAL BLACK 88-89 4555 N/A RED 59-64 4742 N/A IVORY 88-89 4556 N/A FAWN BEIGE 61-62 4947 N/A BURGANDY 88-89 4557 N/A RED 63-64 4835 N/A BEIGE 91 4726 N/A DK BLUE 63-64 4836 N/A VIGOR BEIGE 92 4746 N/A SADDLE 63-64 4837 N/A TAN N/A 5857 N/A CREAMY IVORY N/A 5858 N/A WHITE 64-67 4896 N/A CHARCOAL N/A 5859 N/A RED 65-66 4743 N/A LT SADDLE 65-66 4838 N/A BRIGHT BLUE MET 65-67 4839 N/A DK GREEN 65-67 4840 N/A BRIGHT BLUE 65-67 4737 N/A RED 65-75 4841 ALLANTE (CADILLAC) N/A SILVER 65-75 4842 N/A BLUE 66 4741 Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. N/A BRIGHT BLUE MET 66 4921 N/A TEAL 67 4843 N/A DK SADDLE 67-70 4844 17 CHARCOAL 87-89 4496 N/A DK BRIGHT BLUE MET 68 4891 63 SADDLE 87-89 4498 N/A TOBACCO 68 4946 71 MAROON 87-89 4497 N/A GUNMETAL 68-69 4934 UCV2-1332 DK GOLD 87 5404 UCV2-1335 DK MAROON 87 5405 N/A SADDLE 68-69 4845 UCV2-1369 NATURAL BEIGE 89-90 5417 N/A BRIGHT BLUE 68-70 4738 UCV2-1370 CHARCOAL 89-90 5410 N/A BRIGHT MET BLUE 68-71 4846 UCV2-1422 DK NATURAL BEIGE N/A 5430 N/A DK GREEN MET 69-71 4847 UCV2-1333 MED MAROON N/A 5429 N/A SADDLE 70 4890 N/A DK BLUE 70-75 4848 N/A BLACK 70-84 1501 N/A BLUE 71 4888 425 OXBLOOD 73-74 4740 N/A OXBLOOD 73-75 4849 AUDI N/A MED SADDLE 73-75 4850 N/A NEUTRAL 74-75 4898 Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. -

Saffron—Truffle of the Spice World. in the PANTRY Red Gold

IN THE PANTRY red gold Saffron—truffle of the spice world. RED GOLD BY AMY PATUREL 42 The NaTioNal CuliNary review • oCTober 2014 affron is the most expensive spice on earth, and for good reason. It takes more than 200,000 stigmas, picked by Shand from about 80,000 crocus blossoms, to make just 1 pound of the spice. The cost is a whopping $4,500 a pound. Why bother with such a high-maintenance ingredient? Accord- ing to Nirmala Narine, founder of Nirmala’s Kitchen and TV host of Veria Living’s “Nirmala’s Spice World,” there’s no substitute for the musty, honey-like taste saffron provides. “Just a few threads can color and flavor a dish beautifully,” she says. A prized ingredient in Northern Indian, Spanish and Iranian cuisines—the largest saffron-producing regions in the world— saffron can only be harvested during a two-week flowering period, hence, the moniker “red gold.” Yet it has managed to permeate the culinary landscape in the U.S., appearing in everything from ice cubes and cocktails to ice cream and cake. Saffron is loaded with disease-fighting nutrients, such as vitamin C, thiamin and carotenoids. “Its medicinal properties date back centuries,” says Monica Bhide, author of Modern Spice: Inspired Indian Flavors for the Contemporary Kitchen (Simon & ILLUSTRATION CREDIT Craftsmanspace.com ILLUSTRATION Schuster, 2009). In fact, according to ancient medicinal texts, the legendary spice yields a range of benefits, from antidepressant to aphrodisiac. Ask a chef, though, and you’ll learn that saffron’s greatest power lies in its ability to instantly transform an otherwise drab dish. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

Chalet Nursery Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax

Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax Phormium tenax 'Apricot Queen' Height: 4 feet Spread: 5 feet Spacing: 4 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: (annual) Description: A stunning perennial that has large sword-like leaves that emerge apricot and mature to light yellow with a green margin; beautiful and eye catching as an accent in the garden or massed along borders; also a great center for a Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax mixed container foliage Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder Ornamental Features Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax's attractive large sword-like leaves emerge peach in spring, turning buttery yellow in color with distinctive green edges the rest of the year. Neither the flowers nor the fruit are ornamentally significant. Landscape Attributes Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax is an open herbaceous annual with a more or less rounded form. Its relatively coarse texture can be used to stand it apart from other garden plants with finer foliage. This is a relatively low maintenance plant, and is best Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax cleaned up in early spring before it resumes active growth Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder for the season. Deer don't particularly care for this plant and will usually leave it alone in favor of tastier treats. It has no significant negative characteristics. Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax is recommended for the following landscape applications; - Accent - Mass Planting - General Garden Use - Container Planting 3132 LAKE AVENUE W ILM ETTE, ILLINOIS 60091 847.256.0561 W W W.CHALETNURSERY.COM Planting & Growing Apricot Queen New Zealand Flax will grow to be about 4 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 5 feet. -

A Short History of 18-19Th Century

A SHORT HISTORY OF 18-19TH CENTURY BRITISH HAND-COLOURED PRINTS; WITH A FOCUS ON GAMBOGE, CHROME YELLOW AND QUERCITRON; THEIR SENSITIVITIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON AQUEOUS CONSERVATION TREATMENTS Stacey Mei Kelly (13030862) A Dissertation presented at Northumbria University for the degree of MA in Conservation of Fine Art, 2015 VA0742 Page 1 of 72 Table of Contents List of figures……………………………………………………………………………………...…2 List of tables……………………………………………………………………………………….....2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..………...…3 Research aims, methodology and resources………………………………………………….…....4 1. Aims……………………………………………………………………………………..…...4 2. Research Questions…………………………………………………………………..…...….4 3. Literature review……………………………………………………………………….....….5 4. Case Study Survey………………………………………………………………………..….5 5. Empirical Work……………………………………………………………………………....6 Chapter 1: A Brief History of Hand-coloured Prints in Britain………………………………....6 1.1 The popularity of hand-coloured prints…………………………………………………….....6 1.2 The people behind hand-colouring……………………………………………………..….….9 1.3 Materials and Methods……………………………………………………………………....14 Chapter 2: Yellow Pigments: A focus on Gamboge, Chrome Yellow, and Quercitron……….19 2.1 Why Gamboge, Chrome Yellow, and Quercitron……………………………………….…..19 2.2 Gamboge……………………………………………………………………………….....….20 2.2.1 History…………………………………………………………………………….…....20 2.2.2 Working properties…………………………………………………………………..…21 2.2.3 Physical and chemical properties…………………………………………………..…..21 2.2.4 Methods of -

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade