Middle Class in America (January 2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Systemic Classism, Systemic Racism: Are Social and Racial Justice Achievable in the United States?

Systemic Classism, Systemic Racism: Are Social and Racial Justice Achievable in the United States? THOMAS KLEVEN† I. INTRODUCTION The thesis of this article is that the United States is systemically a highly classist and racist society, that classism and racism are interrelated and overlapping phenomena, and that the achievement of a non- classist/non-racist society requires a mass movement of working-class people of all ethnicities for social and racial justice for all. By systemic classism/racism I mean that the political and economic institutions of the society are structured and operate to systematically disadvantage working-class people in general, and ethnic minorities in particular, and to systematically advantage a relatively small and largely white upper elite class, and a rather substantial and predominantly white upper middle class. By systemic advantage/disadvantage I mean that the opportunities to succeed in life are unequally distributed along class and racial lines, and that society’s institutions produce and perpetuate this class/race hierarchy. The discussion of race focuses primarily on African Americans and Hispanics, both of whom have been systematically disadvantaged on account of ethnicity.1 As the society’s largest disadvantaged minorities, † Professor of Law, Thurgood Marshall School of Law, Texas Southern University. I would like to thank my colleagues who attended and made helpful comments on an earlier draft of the article presented at a Faculty Quodlibet at the law school in November, 2007. I would especially like to thank Asmara Tekle-Johnson for suggestions on how better to organize the article, and Jon Levy for pointing out errors in and suggesting sources for the historical parts of the article. -

Chapter 8: Social Stratification

UNIT 3 238 SOCIAL INEQUALITY Chapter 8 Social Stratification Chapter 9 Inequalities of Race and Ethnicity Chapter 10 Inequalities of Gender and Age Enrichment Readings Chapter 8 – Elliot Liebow “The Lives of Homeless Women,” page 272 Chapter 9 – Patricia Williams “The Skin Color Tax,” page 306 Chapter 10 – Lois Gould “The Story of Baby X,” page 342 239 CHAPTER 8 SocialSocial StratificationStratification 240 U S Your Sections I Sociological N Imagination 1. Dimensions of G Stratification ane Smith, aged forty and reeling from 2. Explanations of a bitter divorce, was discouraged. A se- Stratification Jrious back injury meant she could no longer work at her nursing aide job. 3. Social Classes in America Without a high school diploma, she found that no one was willing to hire her. 4. Poverty in America Reluctantly, she applied for welfare and was enrolled in a program designed to develop 5. Social Mobility job skills. She completed an eighteen-month course and was hired by an engineering firm. After two years, Jane has moved up in Learning Objectives the company and now thinks of herself as an intelligent, capable person. A different type of welfare story involves After reading this chapter, you will be able to Mary, the “welfare queen.” Many politicians have used her as a typical example of how ❖ explain the relationship between stratifica- the social welfare system is abused. Mary tion and social class. managed to register for government aid ❖ compare and contrast the three dimensions under dozens of assumed names and col- of stratification. lected thousands of dollars from food ❖ stamps and other federally subsidized pro- state the differences among the three grams. -

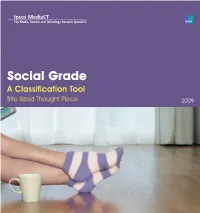

Social Grade a Classification Tool Bite Sized Thought Piece 2009 There Are Several Demographic Classification Systems Used in Market Research

Social Grade A Classification Tool Bite Sized Thought Piece 2009 There are several demographic classification systems used in market research. A well established system, as well as the most widely known and used, is that of social grading, derived from the British National Readership Survey (NRS). Whilst everyone in the industry is familiar with the term social grade and its six groups A, B, C1, C2, D and E, what is less well known is how social grade is defined and how it can be used as a powerful discriminator. Social grade in its current form has been used on the NRS since the 1960s and has provided a valuable insight into changes in the occupational make-up of Britain over time. Ipsos MediaCT has a long association with the NRS and has been the research contractor since 1977. Looking at the last 50 years of NRS data, and taking those classified as AB (higher and intermediate managerial, administrative or professional occupations) as an example, the proportion has increased from 12% to 27%. Social Grade of CIE, 1968-2008 % AB % C1 % C2DE 52 45 65 62 59 29 28 23 22 22 27 12 16 18 21 1968 1978 1988 1998 2008 Source: NRS Social Grade of Chief Income Earner Social % Description Grade population A High managerial, administrative or professional 4 B Intermediate managerial, administrative or professional 23 Supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, C1 29 administrative or professional C2 Skilled manual workers 21 D Semi and unskilled manual workers 15 State pensioners, casual or lowest grade workers, E 8 unemployed with state benefits only Source: NRS 2008 (unweighted sample 37,359, estimated population 15+ (000s) 49,077 How is Social Grade defined? Social grade is a classification system based on occupation and it enables a household and all its members to be classified according to the occupation of the Chief Income Earner (CIE). -

A Socioeconomic Classification for Brazil

Rev. bras. Ci. Soc. vol.2 no.se São Paulo 2006 * A socioeconomic classification for brazil José Alcides Figueiredo Santos ABSTRACT This article presents a new socioeconomic classification for Brazil, applicable to the national social statistics, exposing its theoretical foundations and the operational criteria used in the construction of its empirical categories. Built on a social class approach, this classification intends to contribute to the characterization, description and explanation of the production and reproduction of the durable inequalities that permeate the highly unequal Brazilian society. Using micro data from the 2002 National Household Survey, the article presents the relative distribution of the class categories in the Brazilian society and its income gaps. Finally, it points out some importants results of the process of construct validation of this typology. Keywords: Socioeconomic classification; Social class; Social structure; Class typology; Brazilian society. Introduction This article presents a new socioeconomic classification - applicable to the national statistics of Brazil – , exposing both its theoretical grounds and the operational solutions taken into account in the construction of its empirical categories. Such classification is an instrument that might significantly contribute to a better characterization, description and explanation of the production and reproduction of social inequality in Brazilian society’s concrete conditions. [1] It has been successfully submitted to a process of construct validation which has explored the conditioning effect exerted by the sphere of class inequality, measured by such typology, upon race inequalities in Brazil (Figueiredo Santos, 2005). The sociological approach in conceptualizing and measuring social classes has much to contribute to the understanding of the configuration, evolution and consequences of socioeconomic divisions and their relationships with other forms of durable inequalities which permeate the highly unequal Brazilian society (Tilly, 1999). -

The Problem of Social Class Under Socialism Author(S): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol

The Problem of Social Class under Socialism Author(s): Sharon Zukin Source: Theory and Society, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Nov., 1978), pp. 391-427 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759 Accessed: 24-06-2015 21:55 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656759?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theory and Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 132.236.27.111 on Wed, 24 Jun 2015 21:55:45 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 391 THE PROBLEM OF SOCIAL CLASS UNDER SOCIALISM SHARON ZUKIN Posing the problem of social class under socialismimplies that the concept of class can be removed from the historical context of capitalist society and applied to societies which either do not know or do not claim to know the classicalcapitalist mode of production. Overthe past fifty years, the obstacles to such an analysis have often led to political recriminationsand termino- logical culs-de-sac. -

Petty Bourgeoisie’

Comments on the Term ‘Petty Bourgeoisie’ (S.H. — 4/28/19) Introduction First, I apologize for the length of this essay; as I got into the issue I kept thinking of additional aspects and related topics that should be mentioned. (Of course there are no doubt many more aspects not mentioned here!) And of necessity a discussion about how the petty bourgeoisie is defined must also discuss just how the proletariat and the bourgeoisie should be defined. These are not totally separate issues. Second, in this discussion I am not going to make any distinction between the various English and French spellings: I am taking the most common English term, ‘petty bourgeoisie’ to be the same thing as the ‘petit bourgeoisie’ and the ‘petite bourgeoisie’. Third, it is certainly true that the term ‘petty bourgeoisie’ is used in different ways by different people; i.e., it means different things to different people. Although some other conceptions will be mentioned, I am not setting out to catalog all the many different conceptions and to treat them all with equal validity, as a general lexicographical study would do in creating entries in a standard (bourgeois!) general-purpose dictionary. Instead, I am setting out to say 1) how I think the term has been used within Marxist-Leninist-Maoist theory, and 2) how I think it should be used within that theory in the U.S. today. In other words, I am setting out to define a technical term within MLM theory, but to also talk about a number of additional issues that come up in this regard. -

10 Social Class and Styles of Living

10 Social Class and Styles of Living The concept of social class is crucial to the analysis of society and human behaviour and therefore to any explanation of the existence and scale of poverty. Historically, the concept has played a prominent part in political and sociological theory. In cruder senses, it also plays a prominent part in public discussion of political and social events. It is recognized to be a more complex stratifying factor than, say, age or sex, and emphasis is variously given in its definition and exposition to economic position, power, social status or prestige and culture. In the survey reported in this book, we tried to obtain both objective and subjective indicators of class membership in analysing the distribution of resources. This chapter gives some account of these indicators and the results of using ‘class’ in different senses, as an analytic variable. We developed a number of operational classifications, which are discussed below. They are: 1. Individual unprompted self-assignation. 2. Individual prompted self-assignation. 3. The Registrar General’s five-fold occupational classification. 4. A sociological eight-fold classification. 5. The combined occupational class of husband and wife. 6. The combined occupational class of husband, wife, husband’s father and wife’s father. The Problem of Measurement The state’s acknowledgement of the existence of ‘social class’ might be said to date from the Census of 1911, when the Registrar General sought to grade occupations according to ‘social position’ into eight classes. These were reduced from 1921 to five classes.1 The criteria were arbitrary, and the classification has been frequently criticized. -

FRANTZ FANON and the "LUMPENPROLETARIAT" Peter

FRANTZ FANON AND THE "LUMPENPROLETARIAT" Peter Worsley IN 1960, I attended the All-African People's Congress in Accra, Ghana. The proceedings consisted mainly of speeches by leaders of African nationalism from all over the continent, few of whom said anything notable. When, therefore, the representative of the Algerian Revolutionary Provisional Government, their Ambassador to Ghana, stood up to speak for his country, I prepared myself for an address by a diplomat-not usually an experience to set the pulses racing. Instead, I found myself electrified by a contribution that was remarkable not only for its analytical power, but delivered, too, with a passion and brilliance that is all too rare. I discovered that the Ambassador was a man named Frantz Fanon. During his talk, at one point, he almost appeared to break down. I asked him afterwards what had happened. He replied that he had suddenly felt emotionally overcome at the thought that he had to stand there, before the assembled representatives of African nationalist movements, to try and persuade them that the Algerian cause was important, at a time when men were dying and being tortured in his own country for a cause whose justice ought to command automatic support from rational and progressive human beings. I think this incident reflects one special quality that is characteristic of Fanon's writing also : its passion. It is also ruthlessly honest and highly intellectual, if not always worked-through. It is this special blend of intellect and passion that stamps Fanon's work as the pro- duct of a unique and powerful mind. -

Class, Status, Poverty, and Capital: a Guide to Social Stratification in Career Counseling

Portland State University PDXScholar Counselor Education Faculty Publications and Presentations Counselor Education 7-2013 Class, Status, Poverty, and Capital: A Guide to Social Stratification in Career Counseling Tina M. Anctil Peterman Portland State University, [email protected] Brian Hutchison University of Missouri - St Louis Carol Klose Smith University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/coun_fac Part of the Student Counseling and Personnel Services Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Anctil Peterman, Tina M.; Hutchison, Brian; and Smith, Carol Klose, "Class, Status, Poverty, and Capital: A Guide to Social Stratification in Career Counseling" (2013). Counselor Education Faculty Publications and Presentations. 16. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/coun_fac/16 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Counselor Education Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Class, Status, Poverty, And Capital: A Guide To Social Stratification In Career Counseling Tina Anctil, Ph.D., Portland State University Brian Hutchison, Ph.D., University of Missouri--St . Louis Carol Klose Smith, Ph.D., University of Iowa Nation Career Development Association: Boston, MA Social Class Mad Libs I grew up in a _________ class neighborhood. I knew this because the important adults in my life worked such jobs as __________, ___________, and ___________. I knew growing up that there were people from other classes. One time I remember is when ___________. This made me realize that my class and their class afforded us different outlooks and opportunities. -

Analysis of Inequality Via Social Stratification

Entreciencias: Diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento ISSN: 2007-8064 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Analysis of inequality via social stratification Rodríguez Esparza, Luz Judith; Maza Díaz Cortés, Octavio Martín; Macías Ponce, Julio César; Ortiz Lazcano, Dolly Anabel Analysis of inequality via social stratification Entreciencias: Diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento, vol. 8, no. 22, 2020 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=457662386030 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/enesl.20078064e.2020.2276859e22.76859 PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative CIENCIAS SOCIALES, HUMANIDADES Y ARTES Analysis of inequality via social stratification Análisis de la desigualdad a través de la estratificación social Luz Judith Rodríguez Esparza a [email protected] National Council of Science and Technology [Conacyt], México hp://orcid.org/0000-0003-2241-1102 Octavio Martín Maza Díaz Cortés b [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México hp://orcid.org/0000-0002-3991-7751 Julio César Macías Ponce c [email protected] Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México hp://orcid.org/0000-0001-5141-7074 Dolly Anabel Ortiz Lazcano d [email protected] Entreciencias: Diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento, vol. 8, no. 22, 2020 Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México Universidad Nacional Autónoma de hp://orcid.org/0000-0003-3452-3291 México, México Received: 08 September 2020 Accepted: 03 November 2020 Published: 18 November 2020 Abstract: . DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/ Purpose: To analyze the contribution that social stratification provides to inequality enesl.20078064e.2020.2276859e22.76859 using the Gini index as an input. -

Lower Social Class Does Not (Always) Mean Greater Interdependence: Women in Poverty Have Fewer Social Resources Than Working-Cla

JCCXXX10.1177/0022022114534768Journal of Cross-Cultural PsychologyStephens et al. 534768research-article2014 Article Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2014, Vol. 45(7) 1061 –1073 Lower Social Class Does © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: Not (Always) Mean Greater sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0022022114534768 Interdependence: Women in jccp.sagepub.com Poverty Have Fewer Social Resources Than Working-Class Women Nicole M. Stephens1, Jessica S. Cameron2, and Sarah S. M. Townsend3 Abstract Social resources (i.e., number and nature of relationships with family and friends) are an important, yet largely unrecognized, feature of the sociocultural contexts of social class that influence psychological functioning. To assess the nature and content of social resources, we conducted semistructured interviews with American women living in poverty (n = 21) and working-class (n = 31) contexts. In contrast to previous research, which demonstrates that lower social class contexts foster greater social connection and interdependence than middle- class or upper-class contexts, this study revealed that poverty constitutes a clear cutoff point at which reduced material resources no longer predict higher levels of social connection, but instead social isolation. Our interview data revealed that women in poverty had fewer connections to family and friends, experienced greater difficulty with trust, and reported more challenges involving relationships compared with working-class women. These findings extend psychological theories regarding how social class shapes psychological functioning and have important implications for understanding the maintenance and reproduction of poverty. Keywords social class, poverty, culture, self, inequality, relationships, social integration An emerging body of literature in cultural psychology suggests that social class is a form of cul- ture (D. -

Alexander Hamilton: Slavery, Politics, and Class Status

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-18-2014 Alexander Hamilton: Slavery, Politics, and Class Status Sara Weyenberg Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Nonfiction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weyenberg, Sara, "Alexander Hamilton: Slavery, Politics, and Class Status" (2014). Honors Theses. 2471. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2471 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALEXANDER HAMILTON: SLAVERY, POLITICS, AND CLASS STATUS Sara J. Weyenberg Weyenberg 1 Alexander Hamilton: Slavery, Politics, and Class Status Introduction Though slavery is often connected with the Civil War, it was also a topic of great interest during the Revolutionary period. Many people had strong opinions on the morality of slavery, and they were not afraid to voice them. There are countless writings that, if nothing else, at least touch on the subject briefly. As one might imagine, there were people on both sides of the fence – those who took offense and those who did not. A new country was about to be born, and slavery provided just one of the tensions that was in existence at the time. When so many other issues were at hand, slavery was often placed on the back burner and ignored by many people.