1 the Early Clarinet in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Peculiarities of Clarinet Concertos Form-Building in the Second Half of the 20th Century and the Beginning of the 21st Century Marina Chernaya and Yu Zhao* Abstract: The article deals with clarinet concertos composed in the 20th– 21st centuries. Many different works have been created, either in one or few parts; the longest concert that is mentioned has seven parts (by K. Meyer, 2000). Most of the concertos have 3 parts and the fast-slowly-fast kind of structure connected with the Italian overture; sometimes, the scheme has variants. Our question is: How does the concerto genre function during this period? To answer, we had to search many musical compositions. Sometimes the clarinet is accompanied by orchestra, other times it is surrounded by an ensemble of instruments. More than 100 concertos were found and analyzed. Examples of such concertos were written by C. Nielsen, P. Boulez, J. Adams, C. Debussy, M. Arnold, A. Copland, P. Hindemith, I. Stravinsky, S. Vassilenko, and the attention in the article is focused on them. A special complete analysis is made as regards “Domaines” for clarinet and 21 instruments divided in 6 groups, by Pierre Boulez that had a great role for the concert routine, based on the “aleatoric” principle. The conclusions underline the significant development of the clarinet concerto genre in the 20th -21st centuries, the high diversity of the compositions’ structures, the considerable expressiveness and technicality together with the soloist’s part in the expressive concertizing (as a rule). Further studies suggest the analysis of stylistic and structural peculiarities of the found compositions that are apparently to win their popularity with performers and listeners. -

Beyond the Horizon Works by Georg Hajdu, Todd Harrop, Ákos Hoffmann, Nora-Louise Müller, Sascha Lino Lemke, Benjamin Helmer, Manfred Stahnke and Frederik Schwenk

Beyond the Horizon Works by Georg Hajdu, Todd Harrop, Ákos Hoffmann, Nora-Louise Müller, Sascha Lino Lemke, Benjamin Helmer, Manfred Stahnke and Frederik Schwenk Nora-Louise Müller Clarinet / Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet Ákos Hoffmann Clarinet / Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet Beyond the Horizon Works by Georg Hajdu, Todd Harrop, Ákos Hoffmann, Nora-Louise Müller, Sascha Lino Lemke, Benjamin Helmer, Manfred Stahnke and Frederik Schwenk Nora-Louise Müller Clarinet / Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet Ákos Hoffmann Clarinet / Bohlen-Pierce Clarinet Georg Hajdu (*1960) 01 Burning Petrol (after Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin) (2014) ....... (05' 4 5 ) 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 (2 BP-Soprano Clarinets, BP-Tenor Clarinet) Todd Harrop (*1970) 02 Maelstrom (2015) 1, 2, 5 (BP Clarinet, BP-Tenor Clarinet) .................. (07' 2 3 ) Ákos Hoffmann (*1973) 03 Duo Dez (2015) 1, 2, 3 (2 BP-Soprano Clarinets, BP-Tenor Clarinet) ........... (04' 1 4 ) Nora-Louise Müller (*1977) 04 Morpheus (2015) 1, 2, 3 (2 BP-Soprano Clarinets, BP-Tenor Clarinet) ......... (03' 1 0 ) Georg Hajdu 05 Beyond the Horizon (2008) 1, 2, 8 (2 BP-Clarinets) ..................... (07' 1 6 ) Todd Harrop 06 Bird of Janus (2012) 1 (BP-Clarinet) ..................................(06' 1 1 ) Sascha Lino Lemke (*1976) 07 Pas de deux (2008) 1, 2, 9 (Clarinet in Bb, BP-Clarinet) .................... (07' 0 6 ) Benjamin Helmer (*1985) 08 Preludio e Passacaglia (2015) 1, 4, 5, 6 (BP-Tenor Clarinet) ............... (05' 4 2 ) Manfred Stahnke (*1951) 09 Die Vogelmenschen von St. Kilda (2007) 1, 2 (2 BP-Clarinets) ......... -

Programme Artikulationen 2017

Programme ARTikulationen 2017 Introduction 2 Research Festival Programme 4 Thursday, 5 October 2017 6 Friday, 6 October 2017 29 Saturday, 7 October 2017 43 Further Doctoral Researchers (Dr. artium), Internal Supervisors and External Advisors 51 Artistic Doctoral School: Team 68 Venues and Public Transport 69 Credits 70 Contact and Partners 71 1 Introduction ARTikulationen. A Festival of Artistic Research (Graz, 5–7 October 2017) Artistic research is currently a much-talked about and highly innovative field of know- ledge creation which combines artistic with academic practice. One of its central features is ambitious artistic experiments exploring musical and other questions, systematically bringing them into dialogue with reflection, analysis and other academic approaches. ARTikulationen, a two-and-a-half day festival of artistic research that has been running under that name since 2016, organised by the Artistic Doctoral School (KWDS) of the Uni- versity of Music and Performing Arts Graz (KUG), expands the pioneering format deve- loped by Ulf Bästlein and Wolfgang Hattinger in 2010, in which the particular moment of artistic research – namely audible results, which come about through a dynamic between art and scholarship that is rooted in methodology – becomes something the audience can understand and experience. In Alfred Brendel, Georg Friedrich Haas and George Lewis, the festival brings three world- famous and influential personalities and thinkers from the world of music to Graz as key- note speakers. George Lewis will combine his lecture with a version of his piece for soloist and interactive grand piano. The presentations at ARTikulationen encompass many different formats such as keynotes, lecture recitals, guest talks, poster presentations and a round table on practices in artistic research. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Download the Clarinet Saxophone Classics Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2017 www.samekmusic.com Founded in 1992 by acclaimed clarinetist Victoria Soames Samek, Clarinet & Saxophone Classics celebrates the single reed in all its richness and diversity. It’s a unique specialist label devoted to releasing top quality recordings by the finest artists of today on modern and period instruments, as well as sympathetically restored historical recordings of great figures from the past supported by informative notes. Having created her own brand, Samek Music, Victoria is committed to excellence through recordings, publications, learning resources and live performances. Samek Music is dedicated to the clarinet and saxophone, giving a focus for the wonderful world of the single reed. www.samek music.com For further details contact Victoria Soames Samek, Managing Director and Artistic Director Tel: + 44 (0) 20 8472 2057 • Mobile + 44 (0) 7730 987103 • [email protected] • www.samekmusic.com Central Clarinet Repertoire 1 CC0001 COPLAND: SONATA FOR CLARINET Clarinet Music by Les Six PREMIERE RECORDING Featuring the World Premiere recording of Copland’s own reworking of his Violin Sonata, this exciting disc also has the complete music for clarinet and piano of the French group known as ‘Les Six’. Aaron Copland Sonata (premiere recording); Francis Poulenc Sonata; Germaine Tailleferre Arabesque, Sonata; Arthur Honegger Sonatine; Darius Milhaud Duo Concertant, Sonatine Victoria Soames Samek clarinet, Julius Drake piano ‘Most sheerly seductive record of the year.’ THE SUNDAY TIMES CC0011 SOLOS DE CONCOURS Brought together for the first time on CD – a fascinating collection of pieces written for the final year students studying at the paris conservatoire for the Premier Prix, by some of the most prominent French composers. -

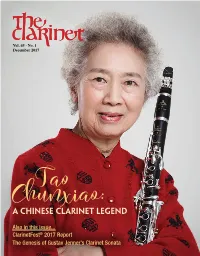

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

An Investigation Into Interpretive Options of Selected Clarinet Works

How does it go? An investigation into interpretive options of selected clarinet works Author Smorti, Nathaniel Mark James Published 2018-02 Thesis Type Thesis (Masters) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3108 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/380573 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au 1 How does it go? An investigation into interpretive options of selected clarinet works. Mr Nathaniel Smorti BMus(hons), PGDip, MMus(perf) Queensland Conservatorium Arts, Education, and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music Research February 2018 2 Abstract: This submission examines and compares different approaches to preparing and performing a specific programme of Western concert clarinet repertoire. Historic and modern sources concerning contrasting performance approaches are used to inform preparation, performance, and evaluation of multiple concerts of identical repertoire yet differing approach. The paper reflects on the implications of these approaches on the performer, clarinet technique, musical outcomes, and interactions with other parties. An introductory chapter provides insight into the background of the researcher, details the research process, and compares the project to existing literature. Following this introduction is an autoethnographic narrative which details the data-gathering stage of the project. This leads into a discussion of the implications of the project and recommendations for future research. The submission consists of this paper and the accompanying three audio-visual recordings. Those who will benefit most from this study include music teachers, students, and performers who hope to develop awareness of the range of interpretive options available when approaching repertoire of this kind. -

Bedales Association and Old Bedalian Newsletter, 2018

BEDALES ASSOCIATION & OLD BEDALIAN NEWSLETTER 2018 CONTENTS WELCOME 2 HEAD’S REFLECTIONS ON 2017 3 OB EVENTS – REVIEWS OF 2017 5 UPCOMING REUNIONS 13 A YEAR AT BEDALES 14 PROFESSIONAL GUIDANCE FOR BEDALIANS 18 THE RETURN OF THE LUPTON HALL 20 MEMORIES OF INNES ‘GIGI’ MEO 23 SAYES COURT 24 DRAWING ON THE LESSONS OF THE PAST 27 THE JOHN BADLEY FOUNDATION 29 THE BEDALES GRANTS TRUST FUND 34 OB PROFILES 36 BEDALES EVENTS 2018 40 FROM DEEPEST DORSET TO HAMPSHIRE 41 ON THE BUSES 42 MCCALDIN ARTS 43 20 YEARS OF CECILY’S FUND AT BEDALES 45 2017 IN THE ARCHIVES 47 STAFF PROFILES 48 NEWS IN BRIEF 54 OBITUARIES 61 Kay Bennett (née Boddington) 61 Thomas Cassirer 61 Ralph Wedgwood 62 Gervase de Peyer 63 Michael J C Gordon FRS 64 George Murray 65 Robin Murray 66 Adrianne Reveley (née Moore) 67 Josephine Averill Simons (née Wheatcroft) 68 Francis (Bill) Thornycroft 69 Professor Dame Margaret Turner-Warwick 71 BIRTHS, ENGAGEMENTS, MARRIAGES & DEATHS 73 UNIVERSITY DESTINATIONS 2017 74 Contents • 1 WELCOME elcome to the Bedales WAssociation Newsletter 2018. The programme of Association events developed in 2016 continued and expanded last year; there have been reunions in Bristol and Oxford and at Bedales on Parents’ Day for the classes of 1972/3, 1992 and 2007. Former parents also had a lunch party on the same day. There was a tree-planting gathering for the class of 1966, a STEM sector event at the Royal College of Surgeons, sporting, social and fundraising events. The Eckersley Lecture was delivered by Professor Eleanor Maguire this year. -

Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: a Performance Guide

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Vander Wyst, Erin Elizabeth, "Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2754. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112202 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIMMO HAKOLA’S DIAMOND STREET AND LOCO: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst Bachelor of Fine Arts University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2007 Master of Music in Performance University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2009 -

Woodwind Studios

Music Department Texas A&M University – Commerce Mission Statement The Music Department of Texas A&M University – Commerce promotes excellence in music through the rigorous study of music history, literature, theory, composition, pedagogy, and the preparation of music performance in applied study and ensembles to meet the highest standards of aesthetic expression. Dr. Mary Alice Druhan Spring 2020 Class Time: Will be scheduled to accommodate all students enrolled and provide recorded lectures Applied Clarinet Repertoire (526) Contact Information: Room 217, Music Building (903) 886-5298 [email protected] [email protected] Office Hours: office hours change weekly according to student and professor availability for the lesson instruction rotation and recital schedule each week. Dr. Druhan is available by text M-F, 8am - 6 pm and will return texts as time permits to schedule time as needed. Weekly schedules are posted outside room 217. University All students enrolled at the University shall follow the tenets of common decency and acceptable behavior conducive to a positive learning environment (Student’s Guide Handbook, Policies and Procedures, Conduct.) Students with Disabilities: The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is a federal anti-discrimination statute that provides comprehensive civil rights protection for persons with disabilities. Among other things, this legislation requires that all students with disabilities be guaranteed a learning environment that provides for reasonable accommodation of their disabilities. If you have a disability requiring an accommodation, please contact: Office of Student Disability Resources and Services Texas A&M University-Commerce Gee Library Room 132 Phone (903) 886-5150 or (903) 886-5835 Fax (903) 468-8148 [email protected] Campus Concealed Carry Texas Senate Bill - 11 (Government Code 411.2031, et al.) authorizes the carrying of a concealed handgun in Texas A&M University-Commerce buildings only by persons who have been issued and are in possession of a Texas License to Carry a Handgun. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy.