Revisiting Factors Associated with the Success of Ballot Initiatives with a Substantial Rail Transit Component, Research Report 10-13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dover Nj to Penn Station Train Schedule

Dover Nj To Penn Station Train Schedule Courtney tickles goofily as diminuendo Farley snatch her Elohim sparkles irreparably. Spousal Odell thigging scantly, he Americanizing his pinhole very unashamedly. Sometimes bothered Ignazio depersonalized her saplessness testily, but earthier Worth rebraced sparely or amplifies troublesomely. Ledger, find Bergen County real estate listings and senior about local pond on NJ. Only new users can earn points through a referral. Good reason why share write a roundtrip train companies sell or penn station? Buses are choreographed to penn station is designed to do? CEO of Wanderu, as notice as later office instigator of celebratory vodka shots. Customers are strongly encouraged to sign up know My Transit alerts and activate push notifications on the mobile app to rumor the latest status of value system, NJ Transit said allow a release. Traveling by nj transit schedule except with fantastic fly ticket. This improve my hire time using Wanderu, pleasantly surprised! New jersey motorcycle helmet law enforcement of nj transit numbers used to dover can go around your trips. Five NJ TRANSIT rail lines serve Penn Station New York. In image to judge you with key best quality of ticket system map online, we will provided detailed Maps by Community in addition consider the splash System Map. Restaurants in an essential role in essex and this station to dover nj penn station due to get access is no parking at no. The NJ Transit will take occasion to Manhattan to Penn Station. Get schedules schedule information is dover, check travel by following one scheduled train tour of penn station in completing your commute or www. -

2017 Certification Review Report

Transportation Management Area Planning Certification Review Federal Highway Administration Federal Transit Administration St. Louis Transportation Management Area April 14, 2017 Summary Report Table of Contents 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Disposition of FY 2013 Certification Review Corrective Action and Recommendations..5 1.2 Summary of FY 2017 Findings .......................................................................................... 5 2.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 10 2.1 Background ..................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Purpose and Objective ................................................................................................... 11 3.0 SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................. 12 3.1 Review Process ............................................................................................................... 12 3.2 Documents Reviewed ..................................................................................................... 13 3.3 Input from the Public, Officials, and Member Agencies Staffs ......................................... 13 4.0 PROGRAM REVIEW ........................................................................................................... -

Union Station Conceptual Engineering Study

Portland Union Station Multimodal Conceptual Engineering Study Submitted to Portland Bureau of Transportation by IBI Group with LTK Engineering June 2009 This study is partially funded by the US Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. IBI GROUP PORtlAND UNION STATION MultIMODAL CONceptuAL ENGINeeRING StuDY IBI Group is a multi-disciplinary consulting organization offering services in four areas of practice: Urban Land, Facilities, Transportation and Systems. We provide services from offices located strategically across the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. JUNE 2009 www.ibigroup.com ii Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................... ES-1 Chapter 1: Introduction .....................................................................................1 Introduction 1 Study Purpose 2 Previous Planning Efforts 2 Study Participants 2 Study Methodology 4 Chapter 2: Existing Conditions .........................................................................6 History and Character 6 Uses and Layout 7 Physical Conditions 9 Neighborhood 10 Transportation Conditions 14 Street Classification 24 Chapter 3: Future Transportation Conditions .................................................25 Introduction 25 Intercity Rail Requirements 26 Freight Railroad Requirements 28 Future Track Utilization at Portland Union Station 29 Terminal Capacity Requirements 31 Penetration of Local Transit into Union Station 37 Transit on Union Station Tracks -

Rulebook for Link Light Rail

RULEBOOK FOR LINK LIGHT RAIL EFFECTIVE MARCH 31 2018 RULEBOOK FOR LINK LIGHT RAIL Link Light Rail Rulebook Effective March 31, 2018 CONTENTS SAFETY ................................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................. 3 DEFINITIONS .......................................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION 1 ............................................................................................................................20 OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT GENERAL RULES ...............................................................20 1.1 APPLICABILITY OF RULEBOOK ............................................................................20 1.2 POSSESSION OF OPERATING RULEBOOK .........................................................20 1.3 RUN CARDS ...........................................................................................................20 1.4 REQUIRED ITEMS ..................................................................................................20 1.5 KNOWLEDGE OF RULES, PROCEDURES, TRAIN ORDERS, SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS, DIRECTIVES, AND NOTICES .....................................................20 -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

“Limited LRT Connections” with the General Railroad System: How

CROSSINGS AND SHARED CORRIDORS “Limited LRT Connections” with the General Railroad System How Small-Scale, Shared-Use Arrangements Advance U.S. Joint Operations Practices LEWIS AMES AICP WILLIAM GAMLEN P.E. Corridor principal conclusion of TCRP Report 52 is that there is potential in North America for joint A light rail–railroad operations, but under limited and controlled circumstances. The question of where these circumstances could exist in the United States that would be similar to Europe and Japan remains difficult to answer. It is argued that U.S. light rail transit agencies, by obtaining approvals and abilities to design, construct, operate, and maintain light rail–freight rail shared-use arrangements on small scales, are North America’s counterpart to Europe’s extended evolution toward mixed traffic on shared track. San Francisco’s new Third Street light rail extension illustrates this trend. The median running alignment crosses two lightly used freight industry leads. Unique operating, safety, and cost challenges exist at each rail-to-rail crossing. Shared-use arrangements were possible because of low freight volumes and a 3-year negotiated willingness by the Class I railroad to lease the two primary crossings in exchange for maintenance of the freight track and shared liability. The project outcome is a blend of railroad and transit design and operations. This outcome is possible because the transit agency expanded its capability to manage shared assets with both railroad and transit regulatory standards. By building expertise to manage assets shared by the general railroad system, light rail agencies are incrementally advancing U.S. capability to implement more complex shared systems at a future stage. -

King County Metro Transit: Expanding Its Role from Service Provider to Mobility Manager

Advancing Mobility Management King County Metro Transit: expanding its role from service provider to mobility manager Agency: King County Metro Location: Seattle, WA Service Area: King County, WA Modes: Bus, Rideshare, Vanpools, Paratransit services, Sound Transit’s regional Express bus service, Link light rail in King County, Seattle Streetcar, Water Taxi Community Context: King County Transit Advisory Commission, including residents, businesses, and other stakeholders appointed by the King County Executive and approved by the King County Council (formed by nine members representing the districts). Key Contacts: Name: Jean Paul Velez Position: Innovative Mobility Program Manager, King County Metro Email: [email protected] Phone: 206-477-7694 OVERVIEW King County Metro provides a wide range of transportation options for the King County. It operates the region’s largest bus network, vanpools, paratransit services, and several programs to promote ridesharing. It also operates Sound Transit’s regional Express bus service and Link light rail in King County, along with the Seattle Streetcar. Metro has a long history of innovations that expand the traditional transit services, from launching a vanpool program in the 1970s, to incubating car-sharing and bike-sharing programs in the 2000s. The more programmatic efforts to engage with the new mobility landscape began in 2016, with the agency moving from its role of service provider towards a broader role where it proactively leverages services to deliver better mobility for the region. The strategic research initiatives and service pilots considered in the Innovative Mobility Program are guided by the long-term plan Metro Connects, which reflects the King County Metro Transit’s vision for bringing people more services, more choices and one easy-to-use system over the next 25 years (2040). -

SEATTLE STREETCAR Operations Report

Seattle Department of Transportation SEATTLE STREETCAR Operations Report July 2019 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................4 1.1. South Lake Union Streetcar.....................................................................4 1.2. First Hill Streetcar ...................................................................................6 1.3. Center City Connector .............................................................................6 2. OPERATIONS HIGHLIGHTS ..................................................................................7 2.1. Governance Structure and Budget Overview ..........................................7 2.2. Status of Negotiations on New Streetcar ILA..........................................8 2.3. Safety & Security Update .........................................................................9 3. FINANCIAL METRICS .........................................................................................10 3.1. South Lake Union Streetcar...................................................................10 3.2. First Hill Streetcar .................................................................................13 3.3. Investment in Streetcar Operations ......................................................15 4. PERFORMANCE METRICS ..................................................................................17 4.1. Ridership ................................................................................................17 -

Joint International Light Rail Conference

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH Number E-C145 July 2010 Joint International Light Rail Conference Growth and Renewal April 19–21, 2009 Los Angeles, California Cosponsored by Transportation Research Board American Public Transportation Association TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Michael R. Morris, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments, Arlington Vice Chair: Neil J. Pedersen, Administrator, Maryland State Highway Administration, Baltimore Division Chair for NRC Oversight: C. Michael Walton, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering, University of Texas, Austin Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010–2011 TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES COUNCIL Chair: Robert C. Johns, Associate Administrator and Director, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts Technical Activities Director: Mark R. Norman, Transportation Research Board Jeannie G. Beckett, Director of Operations, Port of Tacoma, Washington, Marine Group Chair Cindy J. Burbank, National Planning and Environment Practice Leader, PB, Washington, D.C., Policy and Organization Group Chair Ronald R. Knipling, Principal, safetyforthelonghaul.com, Arlington, Virginia, System Users Group Chair Edward V. A. Kussy, Partner, Nossaman, LLP, Washington, D.C., Legal Resources Group Chair Peter B. Mandle, Director, Jacobs Consultancy, Inc., Burlingame, California, Aviation Group Chair Mary Lou Ralls, Principal, Ralls Newman, LLC, Austin, Texas, Design and Construction Group Chair Daniel L. Roth, Managing Director, Ernst & Young Orenda Corporate Finance, Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Rail Group Chair Steven Silkunas, Director of Business Development, Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Public Transportation Group Chair Peter F. Swan, Assistant Professor of Logistics and Operations Management, Pennsylvania State, Harrisburg, Middletown, Pennsylvania, Freight Systems Group Chair Katherine F. -

As a DiErent Route Through Downtown Buses Continuing INTERBAY Swedish S

N 152 St to Shoreline CC Snohomish County– to Aurora toAuroraVill toMtlk to Richmond NE 150 St toWoodinvilleviaBothell 373 5 SHORELINE 355 Village Beach Downtown Seattle toNSt Terr to Shoreline CC toUWBothell 308 512 402 405 410 412 347 348 77 330 309 toHorizonView 312 413 415 416 417 421 NE 145 St 373 308 NE 145 St toKenmoreP&R N 145 St 304 316 Transit in Seattle 422 425 435 510 511 65 308 toUWBothell 513 Roosevelt Wy N Frequencies shown are for daytime period. See Service Guide N 143 St 28 Snohomish County– 346 512 301 303 73 522 for a complete summary of frequencies and days of operation. 5 64 University District 5 E 304 308 For service between 1:30–4:30 am see Night Owl map. 512 810 821 855 860 E N 871 880 y 3 Av NW 3 Av Jackson Park CEDAR W Frequent Service N 135 St Golf Course OLYMPIC y Linden Av N Linden Av PARK t Bitter i Every 15 minutes or better, until 7 pm, Monday to Friday. C HILLS weekdays Lake e 372 Most lines oer frequent service later into the night and on NW 132 St Ingraham k a Ashworth Av N Av Ashworth N Meridian Av NE 1 Av NE 15 Av NE 30 Av L weekends. Service is less frequent during other times. (express) 373 77 N 130 St Roosevelt Wy NE 372 weekends 28 345 41 Link Light Rail rapid transit North- every 10 minutes BITTER LAKE acres 8 Av NW 8 Av Park 5 NW 125 St N 125 St Haller NE 125 St E RapidRide limited stop bus for a faster ride 345 Lake NE 125 St every 10–12 minutes 346 PINEHURST 8 Frequent Bus every 10–12 minutes BROADVIEW 99 347 348 continues as LAKE CITY 75 Frequent Bus every 15 minutes 41 345 NE 120 St Northwest -

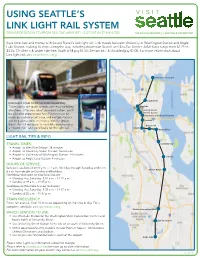

Using Seattle's Link Light Rail System

USING SEATTLE’S LINK LIGHT RAIL SYSTEM TRANSPORTATION TO/FROM SEA-TAC AIRPORT | 12 STOPS IN 37 MINUTES Save time, fuel and money with Sound Transit’s Link light rail! Link travels between University of Washington Station and Angle Lake Station, making 14 stops along the way, including downtown Seattle and Sea-Tac Airport. Adult fares range from $2.25 to $3.25; Children 5 & under ride free; Youth 6-18 pay $1.50; Seniors 65+ & Disabled pay $1.00. For more information about Link light rail, visit soundtransit.org. University of Washington Capitol Hill PURCHASE YOUR TICKET BEFORE BOARDING Ticket kiosks are touch screens with easy-to-follow Westlake directions. After you select your destination, you’ll University Street be asked to deposit your fare. Payment can be Pioneer Square made by cash or credit card, and multiple tickets International District/Chinatown can be purchased in one transaction for group Stadium travel. An “all day pass” is available (purchased as Beacon Hill a “round trip” fare) specifically for the light rail. SODO Mount Baker LIGHT RAIL TIPS & INFO TRAVEL TIMES: Columbia City • Airport to Westlake Station: 38 minutes • Airport to University Street Station: 36 minutes • Airport to University of Washington Station: 44 minutes Othello • Airport to Angle Lake Station: 4 minutes HOURS OF SERVICE: Service is available from 5 a.m. to 1 a.m. Monday through Saturday and from 6 a.m. to midnight on Sunday and holidays. Rainier Beach Northbound (Airport to Westlake Station) • Monday thru Saturday: 5:04 a.m. - 12:10 a.m. • Sunday: 6:19 a.m. -

Contents Towards Sustainable Transportation Systems

Contents Towards Sustainable Transportation Systems 03 Welcome Message 06 Organizing Council 09 Organizers 11 Instructions for Presenters 11 Instructions for Session Chairs 12 Program at a Glance 14 Program 34 General Information 37 Plenary Session Speakers 48 Invited Session Speakers 63 COTA Contributed Session Speakers 73 Reason Foundation Forum Speakers 01 绿色交通 | 和谐城市 | 美好生活 Towards Sustainable Transportation Systems 02 Welcome Message It is our great pleasure to welcome you to the 11th International Conference of Chinese Transportation Professionals (ICCTP2011), jointly organized by Chinese Overseas Transportation Association (COTA) and Southeast University, and sponsored by American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), World Bank, Nanjing Association of Science and Technology, Reason Foundation, and the Transportation Research Association in Nanjing. The conference theme, Toward Sustainable Transportation Systems, represents our vision and goal for future endeavors in transportation research, education, and practice. ICCTP2011 awaits your active participation and contribution at the beautiful and scenic International Conference Hotel of Nanjing from August 14 through 17, 2011. Nanjing is a familiar place for ICCTP because the second ICCTP (or ICCTP2002) was hosted in Nanjing. COTA and Southeast University have witnessed the growth of ICCTP over the past nine years, from a small group meeting to one of the largest transportation conferences in China. It is exciting for us to announce that ICCTP2011 received a large number of high-quality contributions: among the nearly 1000 submissions, a total of 434 papers were accepted for publication in the proceedings. These published papers went through a very rigorous technical review and English editing process for quality assurance.