A Feminist Analysis of Players' Responses to Representations Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asuka Kazama

Asuka Kazama Beitrag von „Daniel“ vom 11. August 2017, 14:41 Hallo zusammen Aus gegebenem Anlass möchte ich hier kurz meine bisher einzige gebaute Figur präsentieren. Die Figur Asuka Kazama stammt aus dem Game Tekken 5 und wurde später in weiteren Tekken-Reihen weitergeführt. Hier findet Ihr weitere Infos zur Spielfigur: http://de.tekken-wiki-german.wikia.com/wiki/Asuka_Kazama Mir persönlich gefiehl die sexy Pose und ich wollte eine Figur, die nicht zu kompliziert scheint, da es für mich Neuland war. Deshalb war ich ganz froh, dass dem Bausatz Decals für die Augen beilagen. Extrem imponiert hat mir die Leistung der Lieferfirma e2046.com Das Paket wurde innert 12 Tagen von Hong Kong in die Schweiz geschickt. Versandspesen nur 5€!! Für die gesamte Ware inkl. Lieferung habe ich 32€ bezahlt. Erstklassige Qualität und tiptop verpackt. Hier die Bilder dazu: IMG_5879.jpgIMG_5880.jpg IMG_5881.jpgIMG_5882.jpg https://www.modellbauforum-koeln.de/index.php?thread/4777-asuka-kazama/ 1 IMG_5883.jpgIMG_5884.jpg IMG_5885.jpgIMG_5886.jpg IMG_5887.jpg Die Base habe ich selbst angefertigt. Entgegen dem ersten Plan, ein Kopfsteinpflaster zu machen, habe ich mich dann für ein Parkett entschieden. Dazu habe ich mir aus dem Baumarkt die passende Holzleiste geholt (2 x 5mm) und in den passenden Längen zugeschnitten und auf die Base geklebt. Die Fugen habe ich mit eingefärbtem Spachtel zugekleistert. Nach kompletter Aushärtung wurde mit einem Dreiecksschleifer alles wieder Plan geschliffen und zuletzt mit einem Seidenglanz Klarlack versehen. Mit dem Ergebnis bin ich sehr zufrieden. Sieht richtig realistisch aus. DSCN9406.jpg DSCN9407.jpg DSCN9408.jpg Und dann habe ich noch ein paar Fotos des Bausatzes. -

Rosedale Open Homepage

SEASON 5, ISSUE 7: May 14th, 2005 The Rosedale Open homepage: http://www.pvv.ntnu.no/~janbu/ropen.html Contents ======== 1. Introduction 2. Broadcast messages 3. Apprentices discovered 4. League results 5. League tables 6. Scorer’s lists 7. Suspensions 8. GMs auction 9. Transferlist 10.Sale to non-league 11. Private trade 12. League matches next issue 13. the Rosedale Knockout 14. GM's ramble 15. List of addresses 1. Introduction Refer to GM's ramble, section 14. 2. Broadcast messages Jaap Smolders, Ajax: «maybe another victory?» Håvard Pettersen, Flaaklypa FK: «hello?» GM's comment: «Are you out there?» Ryoga Hibiki, Furinkan Matsudai Doshitemo: «Konban wa, minna-san!» Andrej Purgemoff, Kremlin: «Treacherous Patina, you shall freeze to death in Siberia.» Jørgen Bjørnelv, Manager Rosewich: «After a while running... you get tired!» Jørgen Bjørnelv, Norwegian Vikings: «BØØ!» Håvard Pettersen, Odd Athletics: «No time to figure out anything clever, so.. Give 'em in guys!» Jaap Smolders, PSV: «Blehhh time to get up again» Alex Trenev, Sofia Inseminaters: «OK, I'm sick of losing. come on, let me beat you!!! PLEASE!» Jerry Horne, Twin Peaks Owls: «Ben, as your attorney, your friend, and your brother, I strongly suggest you get a better lawyer.» 3. Apprentices discovered None. 4. League results Rosedale Open Match day 11 =========================== Grunts United - Dangermouse 6 : 2 Scorers: Trolluc Troeffel (3., 14., 49., 52.), Felix Noyter (37., 66.) *** Buggles Pigeon (70.), Nero Spawn (8.) Booked: --- ***Agent 57, Baron Silas Greenback II Grunts United show fellow relegation strugglers Dangermouse that they are not to be trifled with, and put pressure on MB and CoC right over the relegation line. -

Video Game Lies Revision 3 Is Children Have Different Personalities

Family Friendly Gaming The VOICE of TM the FAMILY in GAMING Tempest 4000, Steamworld Dig 2, Knack II and more in this fabulous is- sue!! ISSUE #124 MX vs ATV All Out will be coming in the year of our November 2017 Lord 2018. CONTENTS ISSUE #124 November 2017 CONTENTS Links: Home Page Section Page(s) Editor’s Desk 4 Female Side 5 Comics 7 Sound Off 8 - 10 Look Back 12 Quiz 13 Devotional 14 Helpful Thoughts 15 In The News 16 - 23 We Would Play That! 24 Reviews 25 - 37 Sports 38 - 41 Developing Games 42 - 67 Now Playing 68 - 83 Last Minute Tidbits 84 - 106 “Family Friendly Gaming” is trademarked. Contents of Family Friendly Gaming is the copyright of Paul Bury, and Yolanda Bury with the exception of trademarks and related indicia (example Digital Praise); which are prop- erty of their individual owners. Use of anything in Family Friendly Gaming that Paul and Yolanda Bury claims copyright to is a violation of federal copyright law. Contact the editor at the business address of: Family Friendly Gaming 7910 Autumn Creek Drive Cordova, TN 38018 [email protected] Trademark Notice Nintendo, Sony, Microsoft all have trademarks on their respective machines, and games. The current seal of approval, and boy/girl pics were drawn by Elijah Hughes thanks to a wonderful donation from Tim Emmerich. Peter and Noah are inspiration to their parents. Family Friendly Gaming Page 2 Page 3 Family Friendly Gaming Editor’s Desk FEMALE SIDE the selfishness we see from too many people person who loves to sleep in. -

Annual Report 2020 1

THUNDERFUL GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 GAMES | DISTRIBUTION WWW.THUNDERFULGROUP.COM THUNDERFUL GROUP ANNUAL REPORT 2020 2 This is a translation of the Swedish Annual Report. In the event of discrepancies, the Swedish version takes precedence. CONTENT ABOUT THUNDERFUL GROUP ....................................................... 3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT ...................................... 33 CEO COMMENT .............................................................................. 5 THE SHARE ..................................................................................... 38 GROUP STRATEGY & TARGETS ......................................................7 NOTES .............................................................................................50 BUSINESS SEGMENT GAMES ........................................................11 AUDITORS REPORT ........................................................................70 BUSINESS SEGMENT DISTRIBUTION ..........................................19 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ................................................................73 INVESTMENT CASE ....................................................................... 23 MANAGEMENT ............................................................................... 75 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT ............................................................. 24 OTHER INFORMATION ..................................................................76 BOARD OF DIRECTORS REPORT .............................................. -

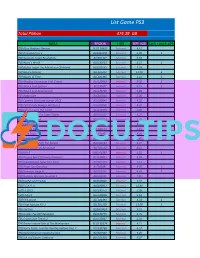

List Game PS3

List Game PS3 Total Pilihan 474.39 GB JUDUL REGION HDD SIZE (GB) ketik 1 untuk pilih [TB] Alice Madness Returns BLUS 30607 External 4.51 [TB] Armored Core V BLJM60378 External 4.00 1 [TB] Assassins Creed Revelations BLES01467 External 8.53 [TB] Asura's Wrath BLUS30721 External 6.52 1 [TB] Atelier Totori The Adventurer Of Arland BLUS30735 External 4.38 [TB] Binary Domain BLES01211 External 11.20 1 [TB] Blades of Time BLES01395 External 2.21 1 [TB] BlazBlue Continuum Shift Extend BLUS30869 Internal 9.30 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Ignition BCJS30077 External 3.15 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Resurreccion BLUS30769 External 3.88 [TB] Bodycount BLES01314 External 5.06 [TB] Cabela's Big Game Hunter 2012 BLUS30843 External 4.10 [TB] Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3 BLUS30838 External 8.02 [TB] Call of Juarez The Cartel BLUS30795 External 5.06 [TB] Captain America Super Soldier BLES01167 External 6.23 [TB] Carnival Island BCUS98271 External 2.73 [TB] Catherine US BLUS30428 External 9.56 [TB] Child of Eden BLES01114 External 2.16 [TB] Dark Souls BLES01402 External 4.62 [TB] Dead Island BLES00749 External 3.46 [TB] Dead Rising 2 Off The Record BLUS30763 External 5.37 [TB] Deus Ex Human Revolution BLES01150 External 8.11 [TB] Dirt 3 BLES 01287 Internal 6.32 1 [TB] Dragon Ball Z Ultimate Tenkaichi BLUS30823 External 6.98 [TB] DreamWorks Super Star Kartz BLES01373 External 2.15 [TB] Driver San Fransisco BLES00891 External 9.05 1 [TB] Dungeon Siege III BLES01161 External 4.50 1 [TB] Dynasty Warriors Gundam 3 BLES01301 External 7.82 [TB] EyePet and Friends BCES00865 Internal 7.47 [TB] F.E.A.R. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Combo Guide by Tekkenomics Mycheatsblog Jul 30, 2007 11:57:56 AM Combo Guide by Tekkenomics

1UP Network: 1UP | GameVideos | MyCheats | GameTab Welcome, Guest [Sign in / Register ] My Page Tracked Games Tracked Boards nbsp; ALL 6 Or Browse by: All | Nintendo DS | PC | PS2 | PS3 | PSP | Wii | Wireless | Xbox 360 post your "ranks" Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection Posted on Apr 14, 2009 for PSP. Also available on Arcade PS3 by ff12fan.1up.com Publisher: Namco Bandai 0 Replies Genre: Fighting Release Date: N/A ESRB Rating: Rating Pending 1UP'S Tekken 5: Dark Resurrection Game Page OVERVIEW SUPERGUIDE FAQS CHEATS FORUM GAME HELP VIDEOS IMAGES FILES FAQ Help [ Back to FAQ Index ] Type Title Contributor Rep Date Added Rating Combo Guide by Tekkenomics MyCheatsBlog Jul 30, 2007 11:57:56 AM Combo Guide by Tekkenomics Type: In -Depth Description: Version: Status: Complete Tekken: Dark Resurrection Wild FAQ Version 1.1 --------- ------- | / | / ------- |\ | | | | / | / | | \ | | |--- |/ |/ |--- | \ | | | |\ |\ | | \ | | | | \ | \ | | \ | | ------- | \ | \ ------- | \| Dark Resurrection (+.[___]·:·) Written by: Kenneth Walton (Wild Man X) Written on: July 8, 2007 E-mail: [email protected] Website: Tekkenomics (Listed below) AIM: Tekkenomics This FAQ version will be available at: Tekkenomics (http://www.tekkenomics.tk) GameFAQs (http://www.gamefaqs.com) Neoseeker (http://www.neoseeker.com) IGN (http://faqs.ign.com) Tekken Zaibatsu (http://www.tekkenzaibatsu.com) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~ ~ ~ Table of Contents ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 1. Version Updates 2. Legal Stuff 3. FAQ Description 4. Legend 5. Legend Explanations 6. Fighter Specific Legend Commands (FSLC) 7. Definitions 8. New Moves / Changed Commands 9. Changed Move Properties 10. Hidden Moves 11. Combo List 12. Customized Outfits 13. Tekken DR PSP Secrets / Unlockables / Nice-To-Know 14. Questions 15. Special Thanks 16. About Tekkenomics 17. About The Author 18. -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

MARVELOUS Company Profile-2019-ENG.Indd

President Shuichi Motoda 2 MARVELOUS COMPANY PROFILE For games, video, music and stage. Excitement has no borders. After food, clothing and shelter comes fun. To have fun is to live. The more we keep our hearts entertained, the more fulfilling our lives will be. Marvelous Inc. is an all-round entertainment company that produces fun. We create interesting and original intellectual property (IP) for games, video, music and stage. Leveraging our strength in “multi-content, multi-use and multi-device,” we transcend changes in the times to consistently create fresh entertainment. We strive to deliver wonder and excitement never seen before to the people of the world. Before you know it, we will be one of Japan’s leading content providers. And we will be an entertainment company that offers a multitude of challenges and thrills and leaves people wondering, “What’s coming next from this company?” Personally, I’m really looking forward to what lies ahead at Marvelous. President Shuichi Motoda MARVELOUS COMPANY PROFILE 3 In the Online Game Business, we are engaged in the planning, development, and operation of online games for App Store, Google Play, and SNS platforms. In order to provide the rapidly evolving online game market quickly and consistently with ONLINE GAME buzz-worthy content, we are engaged in proactive development efforts through alliances with other IPs in addition to our own. By promoting multi-use of original IP produced by Marvelous Delivering buzz-worthy content and and multi-device compatibility of products for PC, mobile, expanding the number of users smartphone, tablet and other devices, we work to diversify worldwide revenue streams. -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

Resident Evil

OPINIÓN EN MODO HARDCORE TodoENERO 2016 JuegosNÚMERO 37 OPINIÓN | REPORTAJES | NOTICIAS | AVANCES UN TORTUOSO VIAJE AL ORIGEN DE RESIDENT EVIL UNA REALIZACIÓN DE PLAYADICTOS Editorial Esperando el renacer ste primer nú- No obstante, creo mero “tradicio- que muchos estamos Enal” de Revista esperando el renacer TodoJuegos del 2016, definitivo de la saga tras el balance de la creada por Shinji Mi- edición anterior, nos kami, con un Resident coloca de cara a una Evil 7 en propiedad, de las sagas favoritas Jorge Maltrain Macho que retome y los orí- de todo gamer aman- Editor General genes de la franquicia te del terror: Resident y modernice la fórmu- Evil de Capcom. Resident Evil Φ que la, es decir, que no deje no tengo dudas que de lado la acción, pero El estudio este mes estará a la altura del tampoco elementos repite la fórmula que original y que será un como el horror, la ex- le dio tanta alegría el gran complemento al ploración o la resolu- año pasado, con una primer título, remas- ción de puzles duran- remasterización de terizado hace un año. te la aventura. Equipo de Revista TodoJuegos DIRECTOR Rodrigo Salas Alejandro Abarca Caleb Hervia #Feniadan #Caleta PRODUCTOR Cristian Garretón EDITOR GENERAL Luis F. Puebla Pedro Jiménez Y DIAGRAMADOR #D_o_G #PedroJimenez Jorge Maltrain Macho No es, por cierto, el por ende, tomarle ca- UNA PRODUCCIÓN DE único caso en el que riño a los personajes esperamos lo mismo (algo básico en todos y en eso este 2016 pa- los juegos buenos de rece pródigo de ejem- la saga), lo cierto es plos, siendo quizás el que su acción más UNA REALIZACIÓN DE más importante de cercana a los Tales todos el caso de Final que a los Final Fan- Fantasy, en lo perso- tasy tradicionales no nal mi saga de rol fa- nos termina por con- ga espera y en medio vorita.. -

“A Jill Sandwich”. Gender Representation in Zombie Videogames

“A Jill Sandwich”. Gender Representation in Zombie Videogames. Esther MacCallum-Stewart From Resident Evil (Capcom 1996 - present) to The Walking Dead (Telltale Games 2012-4), women are represented in zombie games in ways that appear to refigure them as heroines in their own right, a role that has traditionally been represented as atypical in gaming genres. These women are seen as pioneering – Jill Valentine is often described as one of the first playable female protagonists in videogaming, whilst Clementine and Ellie from The Walking Dead and The Last of Us (Naughty Dog 2013) are respectively, a young child and a teenager undergoing coming of age rites of passage in the wake of a zombie apocalypse. Accompanying them are male protagonists who either compliment these roles, or alternatively provide useful explorations of masculinity in games that move beyond gender stereotyping. At first, these characters appear to disrupt traditional readings of gender in the zombie genre, avoiding the stereotypical roles of final girl, macho hero or princess in need of rescuing. Jill Valentine, Claire Redfield and Ada Wong of the Resident Evil series are resilient characters who often have independent storyarcs within the series, and possess unique ludic attributes that make them viable choices for the player (for example, a greater amount of inventory). Their physical appearance - most usually dressed in combat attire - additionally means that they partially avoid critiques of pandering to the male gaze, a visual trope which dominates female representation in gaming. Ellie and Clementine introduce the player to non-sexualised portrayals of women who ultimately emerge as survivors and protagonists, and further episodes of each game jettison their male counterparts to focus on each of these young adult’s development.