Niger: Nutrition Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niger Country Strategic Plan (2020–2024)

Executive Board Second regular session Rome, 18–21 November 2019 Distribution: General Agenda item 7 Date: 25 October 2019 WFP/EB.2/2019/7-A/6 Original: English Operational matters – Country strategic plans For approval Executive Board documents are available on WFP’s website (https://executiveboard.wfp.org). Niger country strategic plan (2020–2024) Duration 1 January 2020–31 December 2024 Total cost to WFP USD 1,055,624,308 Gender and age marker* 3 * https://gender.manuals.wfp.org/en/gender-toolkit/gender-in-programming/gender-and-age-marker/. Executive summary The Niger is a food-deficit, land-locked least developed country ranked last in the 2018 Human Development Index. High levels of food insecurity and malnutrition are exacerbated by environmental degradation, poor natural resource management, rapid population growth, pervasive gender inequalities and climate shocks. Increasing insecurity and the spill over of conflicts induced by non-state groups from neighbouring countries compound these challenges, resulting in forced population displacements. This country strategic plan focuses on supporting government emergency response while implementing integrated resilience activities to protect livelihoods and foster long-term recovery. WFP also aims to strengthen national capacities in order to ensure the sustainability and ownership of zero hunger solutions, for example through measures to make the national social protection system more shock-adaptive and gender-responsive. The plan contains a multisectoral and integrated nutrition package, through which nutrition treatment and inclusive community-led nutrition-sensitive approaches will be aimed at strengthening local food production, promoting girls’ education and improving health and sanitation. The country strategic plan will be gender-equitable and will incorporate gender-transformative approaches to achieving zero hunger, including through the economic and social empowerment of women. -

Lake Chad Basin Fact Sheet #3.Pdf

LAKE CHAD BASIN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #3, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 DECEMBER 22, 2015 NUMBERS AT A GLANCE HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE LAKE CHAD BASIN RESPONSE IN Boko Haram-related insecurity FY 2015–FY 2016 2.5 displaces 2.5 million people; USAID/OFDA1 $30,287,761 displacement increases significantly in million Cameroon and Chad in recent months USAID/FFP2 $77,629,741 People Displaced by Boko USAID/FFP provides nearly $27.2 State/PRM3 $53,300,000 Haram-Related Insecurity million in new funding to WFP in in Lake Chad Basin USAID/Nigeria $33,800,000 OCHA – December 2015 December U.S. Ambassador to Chad James A. Knight redeclares a disaster due to the $195,017,502 4.4 ongoing complex emergency TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE million People in Need of KEY DEVELOPMENTS Emergency Food Assistance in the Region Ongoing Boko Haram-related violence continues to result in insecurity and has displaced OCHA – December 2015 2.5 million people in the Lake Chad Basin as of December. The UN and its partner agencies released the Sahel Regional Response Plan (SRP) on December 9, requesting a total of $1.98 billion dollars to address the Lake Chad Basin crisis, as well as other 2.2 regional crises. In response to increasing displacement resulting from insecurity in neighboring Nigeria, million the International Organization for Migration (IOM) initiated the displacement tracking IDPs in Nigeria matrix (DTM) system in Cameroon. As of mid-November, IOM had identified IOM – November 2015 approximately 158,300 IDPs, including an estimated 124,000 people displaced by Boko Haram-related violence. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Food Insecurity

Emergency appeal n° MDRNE005 Niger: GLIDE n° OT2010000028-NER 29 June 2010 Food Insecurity Appeal target (revised budget): CHF 3,670,607 (USD 3.2 m or EUR 2.2m) <click here to view the attached Revised Emergency Appeal Budget> Appeal coverage: 23% (revised budget); <click here to go directly to the updated donor response report, or here to link to contact details> Appeal history: • This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 18 March, 2010 for CHF 986,862 for nine months to assist 300,000 beneficiaries. • Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF): CHF 229,046 was initially allocated from the Federation’s DREF on 22 February 2010 to support the Red Cross Society of Niger (NRCS) to start the response operation. • Appeal budget revision and extension: due to new reports of the government and partners (19 May, 2010) which raises the severe food insecurity affected population from 2.7 to 3.3 million, the appeal has been revised to CHF 3.65 million and extended until March 2011. • Some 215 villages are already being reached instead of the 120 initially planned. Special Niger Red Cross volunteer screening children for emphasis will be put on: a) meeting emergency referral to centres for treatment of acute food and household needs through cash malnutrition, Tahoua Region, Niger, April 2010 programming, i) addressing the acute malnutrition in children under five by providing community-based screening and referral of acute malnutrition cases, and support for better infant and young child feeding practices through nutrition education, and ii) supporting early recovery through seeds and tools distribution, and improved harvest, iii) strengthening the capacity of the NRCS to deliver the needed services to 384,998 beneficiaries. -

USAID/DCHA Niger Food Insecurity Fact Sheet #4

BUREAU FOR DEMOCRACY, CONFLICT, AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (DCHA) OFFICE OF U.S. FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE (OFDA) Niger – Food Insecurity and Malnutrition Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 September 29, 2010 Note: The last fact sheet was dated July 14, 2010. KEY DEVELOPMENTS In response to increasing food insecurity and deteriorating childhood nutrition, the U.N. World Food Program (WFP) launched an Emergency Operation (EMOP) for Niger on August 1 that aims to provide emergency food assistance to approximately 7.9 million food-insecure people. In August, WFP delivered more than 40,000 metric tons (MT) of emergency food assistance to nearly 3.9 million beneficiaries. In September to date, WFP has delivered more than 25,000 MT of emergency food assistance. To date, donors have provided approximately $151.3 million, or 71 percent, of the total $213 million requested for the EMOP. In late July and August, heavy rainfall caused flooding in Tillabéri, Tahoua, Maradi, Agadez, Niamey, and Zinder regions. Floods had affected more than 226,000 people as of September 3, according to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Floods also damaged more than 5,400 hectares of crops, mainly in Agadez Region. USAID/OFDA-funded programs are responding to acute malnutrition among children under five years of age through community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) and the procurement of ready-to-use therapeutic and supplementary foods and essential medicines. USAID/OFDA has also emphasized economic recovery and livelihood interventions, such as cash-for-work (CFW) and cash transfer programs designed to increase the purchasing power of food-insecure households in pastoral and agricultural areas. -

Emergency Appeal Niger: Food Insecurity

Emergency appeal Niger: Food insecurity Emergency appeal n° MDRNE010 30 January 2012 This Emergency Appeal seeks CHF 3,756,836 in cash, kind, or services to support the Red Cross Society of Niger (RCSN) to assist 350’000 beneficiaries for 9 months, and will be completed by the end of October, 2012. A Final Report will be made available by January 2013 (three months after the end of the operation). CHF 126,768 was allocated from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support this operation. Unearmarked funds to replenish DREF are encouraged. This Emergency Appeal aims to mitigate food shortages resulting from the bad harvests of 2011. This current food shortage is affecting about 3 million people in Niger and millions more over the Sahel region, and is being exacerbated by the rise in prices in the region. According to current estimates from the Niger Ministry of Agriculture and the Director of Statistics, the 2011/12 agro-pastoral season is marked by a deficit of 519,639 tons of cereals (14 percent of the cereal needs of the population) and 10,222,308 tons of forage. As a result, it is anticipated that the lean season will start early—possibly as early as January—instead of March as is customary, and that the affected population will not have the reserves or coping strategies to deal with this extended lean season. Poor and sporadic rainfall resulted in bad harvest. AAccording to the Niger Government, following the results of the Photo: Nathalie Bonvin/IFRC survey Household vulnerability to food insecurity in rural and urban area conducted in November 2011, more than 5,458,000 people (34.9 percent of the population) were in a situation of food insecurity, including 1,324,435 people (8.5 percent) who were severely food insecure. -

Food Insecurity and Complex Emergency

USAI FACT SHEET #12, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 JULY 13, 2012 SAHEL – FOOD INSECURITY AND COMPLEX EMERGENCY KEY DEVELOPMENTS Insecurity in northern Mali due to renewed fighting between militant groups has triggered additional population displacement, both within the country and to neighboring countries. In the last two weeks of June, at least 15,000 Malian refugees arrived at Mbera camp in eastern Mauritania, bringing the total number of camp residents to more than 89,000 people, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR also reported that nearly 6,000 Malians have fled to Niger since June 30. Across the Sahel, many agro-pastoral areas and regions hosting refugees and displaced populations are experiencing food insecurity levels between Stressed—Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) 2—and Crisis—IPC 3—according to the USAID-funded Famine Early Warnings Systems Network (FEWS NET). In June, grain prices in the Sahel averaged 40 to 101 percent above normal seasonal prices, continuing to limit vulnerable households’ access to food. However, FEWS NET reports that rains began normally in parts of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Niger, resulting in timely starts to the annual planting season in these countries. As of July 11, an increasing number of desert locusts had moved into central and southern parts of Niger and begun to breed, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). While insecurity has limited monitoring efforts, FAO believes that a similar situation is underway in northeastern Mali. FAO survey and control teams, in coordination with Malian and Nigerien national teams, are working to protect growing crops from locusts in accessible areas of both countries. -

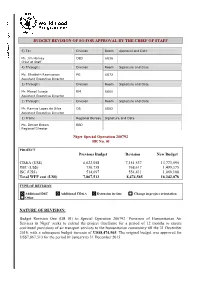

Steps Needed to Approve Budget Revisions

BUDGET REVISION OF SO FOR APPROVAL BY THE CHIEF OF STAFF 5) To: Division Room Approval and Date Mr. Jim Harvey OED 6G36 Chief of Staff 4) Through: Division Room Signature and Date Ms. Elisabeth Rasmusson PG 6G72 Assistant Executive Director 3) Through: Division Room Signature and Date Mr. Manoj Juneja RM 6G00 Assistant Executive Director 2) Through: Division Room Signature and Date Mr. Ramiro Lopes da Silva OS 6G62 Assistant Executive Director 1) From: Regional Bureau Signature and Date Ms. Denise Brown RBD Regional Director Niger Special Operation 200792 BR No. 01 PROJECT Previous Budget Revision New Budget CD&A (US$) 6,622,058 7,151,537 13,773,595 DSC (US$) 730,758 768,617 1,499,375 ISC (US$) 514,697 554,411 1,069,108 Total WFP cost (US$) 7,867,513 8,474,565 16,342,078 TYPE OF REVISION Additional DSC Additional CD&A Extension in time Change in project orientation Other NATURE OF REVISION: Budget Revision One (BR 01) to Special Operation 200792 ‘Provision of Humanitarian Air Services in Niger’ seeks to extend the project timeframe for a period of 12 months to ensure continued provisions of air transport services to the humanitarian community till the 31 December 2016, with a subsequent budget increase of US$8,474,565. The original budget was approved for US$7,867,513 for the period 01 January to 31 December 2015. BACKGROUND: 1. Poverty, demographic pressures and recurrent shocks such as droughts, floods, epidemics, and high food prices are the key causes of vulnerability among households and communities in Niger. -

Revision 2006 Westafrica Eng.Pdf (English)

FRANÇOIS LANDIECH/OCHA RO/NIGER/2005 Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) The CAP is much more than an appeal for money. It is an inclusive and coordinated programme cycle of: • Strategic planning leading to a Common Humanitarian Action Plan (CHAP); • Resource mobilisation (leading to a Consolidated Appeal or a Flash Appeal); • Coordinated programme implementation; • Joint monitoring and evaluation; • Revision, if necessary; and • Reporting on results. The CHAP is a strategic plan for humanitarian response in a given country or region and includes the following elements: • A common analysis of the context in which humanitarian action takes place; • An assessment of needs; • Best, worst, and most likely scenarios; • Stakeholder analysis, i.e. who does what and where; • A clear statement of longer-term objectives and goals; • Prioritised response plans; and • A framework for monitoring the strategy and revising it if necessary. The CHAP is the foundation for developing a Consolidated Appeal or, when crises break or natural disasters strike, a Flash Appeal. Under the leadership of the Humanitarian Coordinator, the CHAP is developed at the field level by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Country Team. This team mirrors the IASC structure at headquarters and includes UN agencies and standing invitees, i.e. the International Organization for Migration, the Red Cross Movement, and NGOs that belong to ICVA, Interaction, or SCHR. Non-IASC members, such as national NGOs, can be included, and other key stakeholders in humanitarian action, in particular host Governments and donors, should be consulted. The Humanitarian Coordinator is responsible for the annual preparation of the consolidated Appeal document. The document is launched globally each November to enhance advocacy and resource mobilisation. -

In Numbers WFP Niger Country Brief Highlights

Highlights • On 24 November, WFP Niger held a debate session on gender-based violence to launch “the 16 days of activism” campaign. • WFP nutrition activities are facing critical funding gaps and treatment activities risk to come to a halt in 2018 without immediate funding. • Results of the Regional Plan for Prevention and Management of Food Crises (PREGEC) published on 29 WFP Niger November highlighted, "A mitigated end of the campaign in the Sahel with prospects of an early and Country Brief difficult lean season in pastoral areas” of Sahel countries including Niger. 6 Month WFP Assistance Providing life-saving Total Total Received Net Funding Requirements (in USD) Strengthening 6 Month support to directly Requirements Total Total Received (in USD) resilience in Niger Net Funding affected by insecurity (in USD)* Requirements (in USD) through an integrated Requirements in northern Nigeria (in USD) multi-sector and (in USD)* 103.6 m 15 m multi-partner safety Regional EMOP 200777 143 m (Jan 2015 – Dec 2017) (72%) net approach 92 m 420.6 m 56.4 m *December 2017 – May 2018 PRRO 200961 (22%) (Jan 2017 – Dec 2019) The Regional Emergency Operation provides flexible *December 2017 – May 2018 assistance through unconditional and conditional food and cash distributions, and nutritional supplementation for children WFP supports the Government in implementing a multi- aged 6-23 months as well as emergency school meals. The sectoral, integrated community-based approach to build assistance is provided to an increasing number of refugees in household, community and system resilience, supporting the and out of camps, returnees, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and host populations affected by the insecurity in same vulnerable people through a flexible combination of northern Nigeria. -

The Impact of Cash and Food Transfers: Evidence from a Randomized Intervention in Niger

The impact of cash and food transfers: Evidence from a randomized intervention in Niger John Hoddinott International Food Policy Research Institute Susanna Sandström World Food Programme and Abo Akademi University, Turku, Finland Joanna Upton Cornell University Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2013 AAEA & CAES Joint Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, August 4-6, 2013. Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Kountche Boubacar Idrissa for supervising the survey team, to Lynn Brown, Gianluca Ferrera, Giorgi Dolidze, Marco Sanguineti and other staff at the World Food Programme for valuable support and conversations and seminar participants at Cornell University for comments on an earlier draft. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Government of Spain received through the World Food Programme. Errors are ours. Corresponding author: John Hoddinott, 2033 K St. N.W., Washington D.C. 20006. [email protected] Key words: cash and food transfers; food security; Niger; randomized intervention Copyright 2013 by John Hoddinott, Susanna Sandström and Joanna Upton. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Abstract We assess the relative impacts of receiving cash versus food transfers using a randomized design. Drawing on data collected in eastern Niger, we find that households randomized to receive a food basket experienced larger, positive impact on measures of food consumption and diet quality than those receiving the cash transfer. Other outcomes showed greater variation by season. Receiving food reduced the use of a number of coping strategies but this effect was more pronounced during the height of the lean season. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background .............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Summary of Classification Conclusions ................................................................................................................................... 1 Food Consumptions Quality .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Food Consumption Quantity ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Nutrition .................................................................................................................................................................................