Niger Food Security Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Rivers Developpement Smartrivers2019

papers_Afri9 SMART RIVERS 2019 Special Session African Rivers developpement Title Country Auteur Company Faisabilit3 de la navigabilit3 sur le Fleuve Niger, Bief Ayourou Gaya Belgium Andr3 Hage DNWT Am3lioration de l2accFs du port de Bra77aville par la navigation France Francis FR.CHART Consultant Design of the navigation channel on the Senegal River Belgium S3bastien PAGE IMDC A new paradigm for river management: Application to the Niger Inner Delta in Mali Belgium 6ean Michel HIVER .LB Spatial altimetry to improve inland navigation in the Congo basin France Sebastien LEGRAND CNR D3veloppement dLun outil dLaide E la navigation sur le bassin du Congo issu dLun Systme dLInformations hydrologiques nouvelle g3n3ration France Damien BR.NEL BRL Page 6 Smart Rivers 2019 Conference / September 30 - October 3, 2019 Cité Internationale / Centre de Congrès Lyon FRANCE / Réf. auteur: Arnaud DE BONVILLER – ISL Ingénierie 25 rue Lenepveu - 49100 Angers France [email protected] Co-auteurs: André HAGE – DN&T Rue de la Belle Jardinière 256, 4031 Liège Belgique [email protected] Seidou SODIA – Ministère de l’équipement (Niger) [email protected] Mots clés: Fleuve africain, navigabilité, cadre juridique, logistique fluviale, exploitation durable, infrastructure Faisabilité de la navigabilité sur le Fleuve Niger, Bief Ayourou-Gaya. Article court Introduction En 2016, le Ministère de l’Equipement Niger a confié à ISL Ingénierie et DN&T l’étude de faisabilité de la navigation sur le Fleuve Niger. La République du Niger est traversée dans sa partie occidentale sur 550 km par le fleuve, principale source en eau de surface qui porte le même nom que le pays. -

Regional Meningitis Surveillance Information Bulletin Situation End of Week 19 (05 to 11.05.03) Date of Report: 24.05.2003 Highlights

World Health Organization - Multi-Disease Surveillance Centre Ouagadougou Regional Meningitis Surveillance Information bulletin_ Situation end of Week 19 (05 to 11.05.03) Date of report: 24.05.2003 Highlights: S Niger : 42 Nm W135 isolated in Niger from week 1 to 18, 2003 in 5 regions out of 8 By regions : Dosso (9), Niamey (15), Tahoua (12), Tillaberi (4) and Zinder (2) S Decreasing trend in all reporting countries Number of Cases and Deaths of Suspected Meningitis Reported to WHO by Countries of the African Meningitis Belt and pathogens identifieda. January 1 - May 11 (Week 19), 2003. Country Reporting Cases Deaths CFR No Nm positive Observations (Epidemic Districts) weeks % Beninb W1 - W19 350 76 21.7 2 Nm W135c Vaccination done in two (None) 6 Nm Ad districts (Tangieta, Toucountouna) Burkina Faso W1 - W19 7,417 1,104 14.9 264 Nm A Laboratory results until week (none) 104 Nm W135 18 Chad W1 – W16 468 72 15.4 N/A No cases week 16 (None) Ghana W1 - W19 1,399 177 12.6 8 Nm A in Bole (None) 11 Nm A in Maprusi 7 Nm A in WA 2 W135 found in none epidemic area Mali W1 - W18 723 49 6.8 16 Nm A No circle in alert (none) 11 Nm W135e Lab results until wekk13 to be cross-checked Niger W1 - W19 7.029 566 8.05 346 Nm A 3 districts still in alert (Magaria,Matameye) 42 Nm W135f Matameye, Magaria, Aguie Significant under reporting. On going CSM activity in Yobbe State but no data available up to date. -

Winds:Towards Better Weather Forecasts in Africa

WINDS:TOWARDS BETTER WEATHER FORECASTS IN AFRICA. KINYODA G. G Kenya Meteorological Department P.o box 30259, Nairobi. KENYA Tel: 56 78 80/Fax: 56 78 88 ABSTRACT: Poor operational meteorological network in Africa has for a long time continued to make weather forecasting difficult. Data extracted from the operational meteorological satellites is therefore vital information for this region. This paper describes, compares and evaluates the operational use of wind information disseminated via the MDD system to Africa; focussing at the Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre (RSMC), Nairobi, the African Centre of Meteorological Applications for Development (ACMAD), Niamey (Niger) and the Drought Monitoring Centre (DMC) in Nairobi. 1. INTRODUCTION 4. SCOPE In describing and evaluating the use of the wind Meteorological services rely heavily on timely information received via the MDD system, this paper :- dissemination of meteorological observations and derived • Discusses briefly the main weather/climate infuencing products.In many parts of the world telecommunications factors in Africa. This is considered important in the links provided by the WMO Global Telecommunications understanding of how the wind information is analysed, System (GTS), which is also used for interchange of interpreted and incorporated into the weather forecasts. meteorological data are satisfactory. However, extensive • Verifies qualitatively, the analysed wind information areas still suffer from a high degree of unreliability. Africa against the validating "truth" provided by a is particularly affected by the unreliability of the GTS. coresponding Meteosat imagery, over a short period. Fortunately, this region lies within the field of view of the • Finally, the MDD’s mission performance is evaluated Meteosat satellite. -

Recent Food Price Developments in Most Vulnerable Countries

RECENT FOOD PRICE DEVELOPMENTS IN MOST VULNERABLE COUNTRIES - ISSUE NO 2, DECEMBER 2008 - This price watch bulletin covers the quarterly period from September to November 2008 . The objective of the bulletin is to provide early warning information on price changes of staple food commodities and their likely impact on the cost of the food basket. Price changes are determined for each country on a quarterly basis. Highlights: • Prices still remain significantly higher compared to last year and long term averages, especially in Eastern and Southern Africa, Asia and Middle East. Overall, the impact on the cost of the food basket remains relatively high. • However, in most of the 36 countries monitored, prices of main staple food commodities have slightly declined over the last three months. • West Africa: Staple food prices were generally stable during the last quarter, except in Benin and Senegal where prices have continued to rise-albeit at a lower rate. The year on year price changes remain higher than changes from long term averages. • East and Southern Africa: The region shows a mixed picture. Half of the countries are still experiencing upward price trends, with significant maize price increases observed in Malawi and Kenya. Prices remain very high compared to their long run averages, especially in the Horn of Africa. The situation remains alarming in Zimbabwe due to hyperinflation . • Asia and Selected Countries: Prices have either remained stable or declined, implying that the cost of food basket in these countries has declined more when compared to other regions such as Africa. However, they remain significantly higher in comparison to the long run averages. -

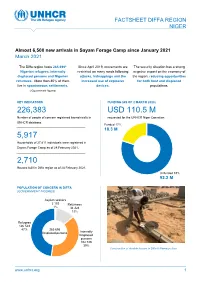

UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR Database

FACTSHEET DIFFA REGION NIGER Almost 6,500 new arrivals in Sayam Forage Camp since January 2021 March 2021 NNNovember The Diffa region hosts 265,696* Since April 2019, movements are The security situation has a strong Nigerian refugees, internally restricted on many roads following negative impact on the economy of displaced persons and Nigerien attacks, kidnappings and the the region, reducing opportunities returnees. More than 80% of them increased use of explosive for both host and displaced live in spontaneous settlements. devices. populations. (*Government figures) KEY INDICATORS FUNDING (AS OF 2 MARCH 2020) 226,383 USD 110.5 M Number of people of concern registered biometrically in requested for the UNHCR Niger Operation UNHCR database. Funded 17% 18.3 M 5,917 Households of 27,811 individuals were registered in Sayam Forage Camp as of 28 February 2021. 2,710 Houses built in Diffa region as of 28 February 2021. Unfunded 83% 92.2 M the UNHCR Niger Operation POPULATION OF CONCERN IN DIFFA (GOVERNMENT FIGURES) Asylum seekers 2 103 Returnees 1% 34 324 13% Refugees 126 543 47% 265 696 Displaced persons Internally Displaced persons 102 726 39% Construction of durable houses in Diffa © Ramatou Issa www.unhcr.org 1 OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Niger - Diffa / March 2021 Operation Strategy The key pillars of the UNHCR strategy for the Diffa region are: ■ Ensure institutional resilience through capacity development and support to the authorities (locally elected and administrative authorities) in the framework of the Niger decentralisation process. ■ Strengthen the out of camp policy around the urbanisation program through sustainable interventions and dynamic partnerships including with the World Bank. -

2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

Niger Page 1 of 3 Niger International Religious Freedom Report 2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, and other laws and policies contributed to the generally free practice of religion. The Government generally respected religious freedom in practice. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the period covered by this report. However, in a few instances local authorities interrupted celebrations of Eid al-Fitr that were on different days than the Government's officially declared end of fasting. There were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice, and prominent societal leaders took positive steps to promote religious freedom. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom with the Government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 490,000 square miles and a population of 14.8 million. Islam is practiced by more than 90 percent of the population. Approximately 95 percent of Muslims are Sunni and 5 percent Shi'a. There are also small communities of Christians and Baha'is. Christians, both Roman Catholics and Protestants, account for less than 5 percent of the population and are present mainly in the regions of Maradi and Dogondoutchi, and in Niamey and other urban centers with expatriate populations. Adherents of Christianity include local believers from the educated, the elite, and colonial families, as well as immigrants from neighboring coastal countries, particularly Benin, Togo, and Ghana. -

Food Insecurity Situations, the National Society (NS) Has Better Equipped Branches, Has Trained More Volunteers and More Technical Staff Are Recruited at Headquarters

DREF operation n° Niger: Food MDRNE005 GLIDE n° OT-2010000028- NER Insecurity 23 February, 2010 The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. CHF 229,046 (USD 212,828 or EUR 156,142) has been allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the Red Cross Society of Niger in delivering immediate assistance to some 300,000 beneficiaries. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: This DREF aims to mitigate the food shortage due to bad harvests last year affecting about half of the population (7.7 million) of Niger. The DREF is issued to respond to a request from the Red Cross Society of Niger (RCSN) to support sectors of food security and nutrition for about Red Cross supported Graham bank in Zinder. 300,000 people with various activities including cash for work, water harvesting and environmental protection actions, seeds and stock distribution, and support to nutrition centres. This operation is expected to be implemented over 2 months, and will therefore be completed by 23 April, 2010; a Final Report will be made available three months after the end of the operation (by July, 2010). An emergency appeal is in preparation to extend the activities until the harvest time in October or November, 2010. -

Niger Country Strategic Plan (2020–2024)

Executive Board Second regular session Rome, 18–21 November 2019 Distribution: General Agenda item 7 Date: 25 October 2019 WFP/EB.2/2019/7-A/6 Original: English Operational matters – Country strategic plans For approval Executive Board documents are available on WFP’s website (https://executiveboard.wfp.org). Niger country strategic plan (2020–2024) Duration 1 January 2020–31 December 2024 Total cost to WFP USD 1,055,624,308 Gender and age marker* 3 * https://gender.manuals.wfp.org/en/gender-toolkit/gender-in-programming/gender-and-age-marker/. Executive summary The Niger is a food-deficit, land-locked least developed country ranked last in the 2018 Human Development Index. High levels of food insecurity and malnutrition are exacerbated by environmental degradation, poor natural resource management, rapid population growth, pervasive gender inequalities and climate shocks. Increasing insecurity and the spill over of conflicts induced by non-state groups from neighbouring countries compound these challenges, resulting in forced population displacements. This country strategic plan focuses on supporting government emergency response while implementing integrated resilience activities to protect livelihoods and foster long-term recovery. WFP also aims to strengthen national capacities in order to ensure the sustainability and ownership of zero hunger solutions, for example through measures to make the national social protection system more shock-adaptive and gender-responsive. The plan contains a multisectoral and integrated nutrition package, through which nutrition treatment and inclusive community-led nutrition-sensitive approaches will be aimed at strengthening local food production, promoting girls’ education and improving health and sanitation. The country strategic plan will be gender-equitable and will incorporate gender-transformative approaches to achieving zero hunger, including through the economic and social empowerment of women. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

1 NIGER WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Reporting Date: From

NIGER WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Reporting date: From 20thJuly to 26th August 2012 I. Overview At least 44 people have been killed and thousands more made homeless after heavy floods caused the Niger River to overflow earlier this week, flooding parts of the capital Niamey and other areas. Up to 340,000 people have been affected by the floods, Niger's government has said. It has declared a state of emergency and called for urgent international aid for 2,000 displaced people. The first foreign aid plane chartered by Ireland and bringing tents, mosquito nets and ther relief items to victims of Niger's flood in Dosso area, arrived Sunday in Niamey. UNHCR has agreed to contribute to the inter-agency humanitarian response and has in that respect released 900 of the 2000 Plastic sheeting it plans to make available. UNHCR participated in a UN agencies joint evaluation mission in the Tillabery area aimed at identifying special assistance needs for the disaster stricken population following the recent floodings In total, 172 new households of 961 individuals have been registered in the three camps during the studied week. Arrivals are now slow but steady. II - Major Developments The general situation remains calm in the country. During the week under report, the frequent rains have caused floods throughout Niger. As a consequence access to the camps are made even more difficult. In terms of damage caused to physical infrastructure the camps have been relatively spared except for Tabareybayrey. The heavy wind and the rains from the 18th and 19th have destroyed several of the MSF tents building which serves as medical center,with serious damages to medical equipments and medical supply. -

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of Cerf Funds Niger Rapid Response Conflict-Related Displacement

RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS NIGER RAPID RESPONSE CONFLICT-RELATED DISPLACEMENT RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Mr. Fodé Ndiaye REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. Since the implementation of the response started, OCHA has regularly asked partners to update a matrix related to the state of implementation of activities, as well as geographical location of activities. On February 26, CERF-focal points from all agencies concerned met to kick off the reporting process and establish a framework. This was followed up by submission of individual projects and input in the following weeks, as well as consolidation and consultation in terms of the draft for the report. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO The CERF Report has been shared with Cluster Coordinator and recipient agencies. 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: 53,047,888 Source Amount CERF 5,181,281 Breakdown -

Niger Country Brief: Property Rights and Land Markets

NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison with Peter C. Bloch Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison Under Subcontract to Development Alternatives, Inc. Financed by U.S. Agency for International Development, BASIS IQC LAG-I-00-98-0026-0 March 2003 Niger i Brief Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of the country brief 1 1.2 Contents of the document 1 2. PROFILE OF NIGER AND ITS AGRICULTURE SECTOR AND AGRARIAN STRUCTURE 2 2.1 General background of the country 2 2.2 General background of the economy and agriculture 2 2.3 Land tenure background 3 2.4 Land conflicts and resolution mechanisms 3 3. EVIDENCE OF LAND MARKETS IN NIGER 5 4. INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS 7 4.1 The colonial regime 7 4.2 The Hamani Diori regime 7 4.3 The Kountché regime 8 4.4 The Rural Code 9 4.5 Problems facing the Rural Code 10 4.6 The Land Commissions 10 5. ASSESSMENT OF INTERVENTIONS ON PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKET DEVELOPMENT 11 6. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY 15 APPENDIX I. SELECTED INDICATORS 25 Niger ii Brief NIGER COUNTRY BRIEF: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND LAND MARKETS Yazon Gnoumou with Peter C. Bloch 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE COUNTRY BRIEF The purpose of the country brief is to determine to which extent USAID’s programs to improve land markets and property rights have contributed to secure tenure and lower transactions costs in developing countries and countries in transition, thereby helping to achieve economic growth and sustainable development.