Copyright by Frances Lourdes Ramos 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

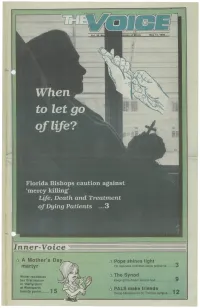

When to Let Go of Life?

Vol.36 Noj locese of Miami Mav 12. 1989 When to let go of life? Florida Bishops caution against 'mercy killing1 Life, Death and Treatment of Dying Patients . • • 3 Inner-Voice A A Mother's Day A Pope shines light martyr On darkness of African social problems O Writer recollects A The Synod her first lesson Keeping the dream alive is next *7 in 'martyrdom' at Woolworth A PALS make friends beauty parlor 15 Group blossoms on St. Thomas campus I dL World / NatiQtia mmmsig- National: U.S. bishops lend support to Panama peace efforts WASHINGTON (NC) — The head of the U.S. bishops' conference has expressed support for the Panamanian bishops' efforts on behalf of a peaceful solution to conflicts in their country. Four days be- fore the May 7 Panamanian elections, Archbishop Nun John L. May of St. Louis, president of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, wrote the head of arrested the Panamanian bishops to commend an April 5 pastoral letter they issued for "upholding, the values Police officers of true democracy and justice." "I hope and pray in Livonia, that its wise counsel will be seriously considered and Mich., drag widely accepted," Archbishop May wrote to Bishop away a nun Jose Dimas Cedeno Delgado of Santiago de Vara- guas, head of the Panamanian bishops' conference. who was arrested in i California Catholics plan benefits abortion to help fund AIDS research protest. The SAN FRANCISCO (NC) — A major rock concert, nun declined other musical events and a telethon are among spring to give her activities which will benefit a San Francisco arch- name when diocesan program for people with AIDS or AIDS- asked. -

Texto Completo

DE PUEBLA A SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA: MÁS NOTICIAS SOBRE EL BEATO SEBASTIÁN DE APARICIO, EL FRAILE CARRETERO De Puebla a Santiago de Compostela: más noticias sobre el beato Sebastián de Aparicio, el fraile carretero CARMEN MANSO PORTO* Biblioteca de la Real Academia de la Historia Sumario Se ofrecen nuevas aportaciones a la biografía y representaciones artísticas de Sebastián de Aparicio en relación con el proceso de su beatificación, que completan el trabajo publicado en 2018 en esta misma Revista1. Abstract New contributions to the biography and artistic representations of Sebastián de Aparicio are offered in relation to the process of his beatification, which complete the work published in 2018 in this same Magazine. l beato Sebastián de Aparicio (A Gudiña-Ourense, 20-01-1502 / Puebla de Elos Ángeles, 25-02-1600) dejó una importante huella en el virreinato de Nueva España. Como agricultor y constructor de carretas, contribuyó a la mejora de las condiciones de trabajo de los indios en el campo y en las minas. El duro acarreo de las mercancías en recuas de mulas y a hombros de los indios tamemes, dio pasó a su transporte en carretas arrastradas por yuntas de bueyes. Durante los últimos veintidós años de su vida, Aparicio ejerció el oficio de fraile limosnero en el convento franciscano de Puebla de los Ángeles y trabajó como carretero recogiendo alimentos y enseres para la comunidad. Su fama de santidad y de trabajador infatigable al servicio de los pobres se extendió por toda la zona. Falleció al mes de haber cumplido los 98 años. Su cadáver amortajado fue velado y, desde entonces, comenzaron los relatos de sus milagros. -

Shrines of Mexico Spiritual Director: Fr. Ron Schock November 28 - December 4, 2018

Shrines of Mexico Spiritual Director: Fr. Ron Schock November 28 - December 4, 2018 Day 1 - Nov 28: Depart from DTW for your flight to Mexico City. Upon arrival, transfer to the city of Puebla, “The City of the Angels.” We will stay at a colonial hotel in downtown, close to churches, restaurants, and shops. (D) Day 2 - Nov 29: Puebla - After breakfast, Mass at the Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary in the Church of Santo Domingo, continuing to the Cathedral and the church of St. Francis of Assisi to view the body of Blessed Sebastian de Aparicio whose body remains incorrupt until today. Lunch will be served at a local restaurant followed by some time to shop in El Parian, a handcraft market where it is possible to find Puebla’s famous Talavera pottery. (B, L) Day 3 - Nov 30: Tlaxcala - After breakfast, we will visit the Shrine of San Miguel del Milagro, site of St. Michael’s apparition to Diego Lazaro, in Tlaxcala. Mass will be held at the Shrine of Our Lady of Ocotlan where Our Lady appeared to Juan Diego Bernardino in 1541. In colonial times, they used open chapels to teach the indigenous peoples the Holy Mass. It is a real treat to be able to visit one of the most beautiful open-chapels in the country! Lunch will be served at a local restaurant prior to departing for Mexico City to check in at our centrally-located hotel. (B, L) $2,249.00 per person, Cash/Check Day 4 - Dec 1: Mexico City - On the way to the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, discount, double occupancy. -

El Agricultor Gallego Sebastián Aparicio Promotor Del Transporte De Mercancías En Carretas En El Virreinato De Nueva España

... SEBASTIÁN APARICIO PROMOTOR DEL TRANSPORTE ... EN CARRETAS EN ... NUEVA ESPAÑA El agricultor gallego Sebastián Aparicio promotor del transporte de mercancías en carretas en el Virreinato de Nueva España CARMEN MANSO PORTO* Resumen Sebastián de Aparicio fue uno de los muchos españoles que embarcaron en la Flota de Indias en busca de fortuna. Desde 1533, residió en Puebla de los Ángeles y trabajó como agricultor y constructor de carretas para transportar mercancías a la ciudad de México, capital del Virreinato. Más tarde colaboró en el trazado y en las actividades comerciales del camino México-Veracruz y del Camino de Tierra Adentro, cuando se descubrieron las minas de plata de Zacatecas. En la última etapa de su vida ingresó en la Orden de San Francisco y ejerció como limosnero recorriendo los caminos con su carreta de bueyes para el mantenimiento de los frailes. Por eso se le conoce como El Fraile Carretero. Fue beatificado en 1789. Se le considera el primer constructor de carretas en Nueva España y es el patrón de los transportes terrestres. Abstract Sebastián de Aparicio was one of the many Spaniards who embarked on the Flota de Indias in search of fortune. From 1533, he lived in Puebla de los Angeles and worked as a farmer and cart builder to transport goods to Mexico City, capital of the Viceroyalty. Later he collaborated in the layout and commercial activities of the Mexico-Veracruz path and the Camino de Tierra Adentro, when the silver mines of Zacatecas were discovered. In the last stage of his life he entered the Order of San Francisco and served as a almoner walking the paths with his ox cart for the maintenance of the friars. -

The Church of San Francisco in Mexico City As Lieux De Memoire

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses Architecture 5-2013 The hC urch of San Francisco in Mexico City as Lieux de Memoire Laurence McMahon University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Latin American History Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation McMahon, Laurence, "The hC urch of San Francisco in Mexico City as Lieux de Memoire" (2013). Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses. 6. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Church of San Francisco, as the oldest and first established by the mendicant Franciscans in Mexico, acts as a repository of the past, collecting and embodying centuries of memories of the city and the congregation it continues to represent. Many factors have contributed to the church's significance; the prestige of its site, the particular splendor of ceremonies and rituals held at both the Church and the chapel of San Jose de los Naturalés, and the liturgical processions which originated there. While the religious syncretism of some churches, especially open air chapels, has been analyzed, the effect of communal inscription on the architecture of Mexico City is an area of study that has not been adequately researched. This project presents a holistic approach to history through memory theory, one which incorporates cross-disciplinary perspectives including sociology and anthropology. -

Material Conditions 1 in Part One, We Saw That the Relationship Between Women's Institutions and Society in Early Colonial Mexico City Was Distinctive

Escogidas Plantas: Chapter 8 4/24/03 6:56 PM 8. Material Conditions 1 In Part One, we saw that the relationship between women's institutions and society in early colonial Mexico City was distinctive. The period gave rise to institutions for women at a dramatic rate, and their foundations both reflected and participated in the transformation of an Amerindian city and the creation of a settler society. Given the distinctiveness of the role of such institutions in this period, it seems appropriate now to examine the extent to which women's experience of religion in the sixteenth century was also distinctive, differing from or paralleling what has come to be seen as characteristic colonial women's religion. We begin with an attempt to reconstruct the material conditions in which women of devotion lived their lives. Popular perceptions of women's institutions in colonial Spanish America have long been colored by the nineteenth-century "liberal" view of convents as country clubs where rich criollas lived in luxurious irrelevance. "Typical" nunneries have often been presented as massive, enormously rich and luxurious houses, often containing as many as five hundred women - nuns, boarders, novices, and servants. These institutions, we are told, were virtual cities within the city, bristling with barbs that excluded the curious eye and imposed absolute clausura. 1 Inside the imposing walls were lighted streets with individual "cells," made up of three to four rooms. Here the communal life prescribed by monastic rules was nowhere in evidence. The cells were the homes of the professed nuns, who lived in them with their servants and the girls in their charge, dining on food prepared in their own private kitchens. -

Shrines of Mexico

Nativity Terms and Conditions Pilgrimage 9-Day Pilgrimage to the Shrines of Mexico Led by Fr. Juan Carlos López and Deacon Guadalupe Rodríguez September 12 – 20, 2021 Cost Round-Trip Air from $2,649 per person Austin, TX For more information, please contact Deacon Guadalupe Rodríguez (512) 364-2795 | [email protected] or visit: https://nativitypilgrimage.com/frjuan-dcnguadalupe Follow Us on Social Media! nativitypilgrim nativitypilgrimage @nativitypilgrimage Daily Itinerary Inclusions • Round-trip airfare • Land transportation as per itinerary • Hotel accommodations • Breakfast and dinner • Airport taxes, fuel surcharges, and fees • Daily Mass • Protection Plan (medical insurance) Non-Inclusions • Tips for your guide and drivers • Lunch • Optional Deluxe Protection Plan (trip cancellation benefits) • Items of a personal nature Day 1: Arrival In Mexico / Teotihuacan Register Now Sep Today: Upon arrival at the Mexico City airport we meet with our tour guide who will take us to Teotihuacan to see • Fill out registration form included in this 12 the ancient Pyramids of the sun and the moon. After the visit we proceed to our hotel. brochure. Ask your spiritual director and/or Evening: We check in to our hotel in Mexico City followed by mass and tour coordinator or contact us if you do not dinner. have this form. Day 2: Shrine Of Our Lady Of Guadalupe • Mail your form and non-refundable deposit Sep Today: After breakfast, we go to the Shrine of Our Lady of $300 in check or money order to the of Guadalupe (Patroness of the Americas) where 8 – 10 address at the bottom of the registration 13 million Aztecs converted soon after the Marian apparitions in 1531. -

THE Mexican Guide

Class _Illl^_i: Book ___:1j_ COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT 4 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from Tine Library of Congress littp://www.arcliive.org/details/mexicanguideOOjanv Public Buildings. CITY OF MEXICO AcadcmiatleBclhis Artcs.O, 103 AX7TH0BIZED FOR PtTBLIC ATION WITH THE MEXICAIN GUIDE By GENERAL CARLOS PACHECO, Minister of Piibltv H'or, U-a, 18fi5. I TO TOURISTS AND OTHERS about to visit Mexico, The Missouri Pacific Rail- way System offers a choice of the pleasantest and most direct routes from St. Louis, Chicago, Kansas City, and also (via Texas and Pacific Railway) from GALVESTON and New Orleans. From all above points connection is made at El Paso, Texas, with the Mexican Central Railway, so that via either of the MISSOURI PACIFIC routes passengers can be sure of a Speedy and Comfortable trip to Mexico. Pullman, Sleeping, Dining, and Buffet Cars of the newest and best patterns through to El Paso in all express trains. For further information apply to W. H. NEWMAN, Gen'l Traffic Manager, ) ^'^' ^O^'S, MO. H. C. TOWNSEND, Gen'l Pas. & Ticket Agt., \ O. G MURRAY, Traffic Manager, ) DALLAS, B. W. McCULLOUGH, Gen'l Pas. & Ticket Agt., f TEXAS. JNO. E. ENNIS, Pas. Agt., S. H. THOMPSON, Cent. Pas.Agt., 86 Washington St., Chicago. iiig Liberty St., Pittsburg, Pa. A. A. GALLAGHER, So. Pas. Agt., N. R. WARWICK, Pas. Agt., 103 Read House, Chattanooga, Tenn. 131 Vine St., Cincinnati, O. E. S. JEWETT, Pas. & Ticket Agt., A. H. TORRICELLI,New Eng.Agt., 528 Main St., Kansas City, Mo. 214 Washington St., Boston, Mass. -

Mexico City & Guadalupe

Join Fr. Przemyslaw J Nowak on a Jubilee Pilgrimage in the Year of Mercy to Mexico City & Guadalupe MEXICO CITY * GUADALUPE * TLAXCALA * PUEBLA November 10-15, 2016 $2,099 Per Person from Newark, NJ based on double occupancy www.pilgrimages.com/frnowak HIGHLIGHTS OF INCLUS IONS: ROUND-TRIP AIRFARE FROM NEWARK, AIRLINE FUEL SURCHARGES & AIRPORT TAXES, ACCOMMODATIONS FOR 5 NIGHTS, ASSISTANCE OF PROFESSIONAL CATHOLIC TOUR GUIDE(S), SPIRITUAL DIRECTION, SIGHTSEEING AND ADMISSIONS FEES, BREAKFAST & DINNERS WITH WINE, LUNCHES DAILY (EXCLUDING FLIGHT DAYS) , TRANSPORTATION BY PRIVATE MOTOR COACH, MASS DAILY & SPIRITUAL ACTIVITIES, LUGGAGE HANDLING, FLIGHT BAG & PORTFOLIO. The Shrine at Guadalupe is considered the holiest Housed within the Plaza is the first rosary shrine in place in the Western Hemisphere. President John F. Mexico, Our Lady of the Rosary; and a second shrine, Kennedy and French President Charles de Gaulle testified Our Lady of Covadonga (headquarters of the to this during state visits to Mexico. St. John Paul II Confraternity of the Most Holy Rosary, founded in preached to millions of the faithful from this holy Shrine 1538). Dinner and overnight. during his 1979 visit to Mexico. The Basilica commemorates the Virgin Mary's appearance to a humble Indian and honors her request that a Shrine be November 13, 2016: Tlaxcala & Puebla Tour built in Her honor. In December of 1531, Juan Diego Following breakfast, we will leave Mexico City for a informed a skeptical bishop of his encounter with Mary. A spectacular ride with a view of the two most famous few days later, Juan returned to the site of the vision and peaks, one covered with eternal snow, and next to it is once again Our Mother appeared. -

Our Lady of Ocotlán and Our Lady of Guadalupe: Investigation Into The

Universite de Montreal Our Lady of Ocotlan and Our Lady of Guadalupe: Investigation Into the Origins of Parallel Virgins par Stephanie Rendino Faculte de Theologie These presentee a la Faculte des etudes superieures en vue de l'obtention du grade de Doctorat Canonique en theologie aout 2007 ©Stephanie Rendino, 2007 /<& of °+ •& N^®" 6 compter du" V^ 0 1 MAI 2008 ^cfe^ Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49890-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49890-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Summary of Catholic History

A SUMMARY OF CATHOLIC HISTORY By Newman C. Eberhardt, G.M. VOLUME II MODERN HISTORY B. HERDER BOOK CO. 15 & 17 South Broadway, St. Louis 2, Mo. AND 2/3 Doughty Mews, London, W.C.1 IMPRIMI POTEST JAMES W. STAKELUM, C.M., PROVINCIAL IMPRIMATUR: ►j4 JOSEPH CARDINAL RITTER ARCHBISHOP OF ST. LOUIS-OCT. 16, 1961 © 1962 BY B. HERDER BOOK CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 61-8059 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY VAIL-BALLOU PRESS, INC., BINGHAMTON, N.Y. Contents PART I: THE CHURCH IN THE HUMANIST WORLD Section I: Secular Humanism (1453-1776) I. THE RENAISSANCE (1447-1517) . 4 1. The Secular Renaissance .. • 4 2. The Ecclesiastical Renaissance .. • 11 3. The Renaissance Papacy (1447-84) . 17 4. The Evil Stewards (1484-1503) . 23 5. The Militant and Humanist Papacy (1503-21) . 30 6. Germanic Renaissance (1378-1519) . 36 7. Slavic Renaissance (1308-1526) . 42 8. French Renaissance (1380-1515) . 47 9. British Renaissance (1377-1509) . 53 10. Iberian Unification (1284-1516) 59 11. Scandinavian Unity (1319-1513) . 65 II. EXPLORATION AND EVANGELIZATION (1492-1776) 71 12. The Turkish Menace (1481-1683) .. 71 13. Levantine Missions 74 14. Return to the Old World ..... 80 15. Discovery of a New World (1000-1550) • 87 16. Latin America (1550-4800) ... 93 17. French America (1603-1774) ... • 104 18. Anglo-Saxon America (1607-1776) . 114 Section II: Theological Humanism (1517-1648) III. THE PROTESTANT REVOLUTION (1517-59) . 124 19. Causes of Protestantism 124 20. Emperor Charles of Europe (1519-58) . 132 21. Luther and Lutheranism .. -

Copyright by Cornelius Burroughs Conover V 2008

Copyright by Cornelius Burroughs Conover V 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Cornelius Burroughs Conover V certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A SAINT IN THE EMPIRE: MEXICO CITY’S SAN FELIPE DE JESUS, 1597-1820. Committee: ___________________________________ Ann Twinam, Supervisor ___________________________________ Jorge Canizares-Esguerra ___________________________________ Virginia Garrard-Burnett ___________________________________ Alison Frazier ___________________________________ Enrique Rodriguez-Alegria ________________________________________________________________________ A SAINT IN THE EMPIRE: MEXICO CITY’S SAN FELIPE DE JESUS, 1597-1820. by Cornelius Burroughs Conover V, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2008 Acknowledgments. The completion of this dissertation gives me the opportunity to recognize those who have helped make it possible. I owe thanks to the University of Texas at Austin for the financial wherewithal to support myself while finishing the project. However, the intellectual milieu that the university provided from 2001 to 2007 was, perhaps, more important to my development as a scholar. Without the academic community of professors and fellow students at Texas, this project would never have taken the form it did. I am indebted to Ann Twinam, my dissertation advisor, who read many drafts of the work and who deserves credit for improvements too numerous to elaborate. Special thanks go to Jorge Cañizares as a welcome source of energy, of inspiration and of bold ideas. I am grateful to Alison Frazier for her insistence on preciseness and for her gracious scholarship.