Journal of Early Modern Christianity 2017; 4(2): 195–225

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professor Yulia MIKHAILOVA: Curriculum Vitae Amd Publications

Hiroshima Journal of International Studies Volume 19 2013 Professor Yulia MIKHAILOVA: Curriculum Vitae amd Publications Curriculum Vitae Date of Birth: February 23,1948 Nationality: Australia; Permanent Resident of Japan Educational Background 1966.09 − 1972.02 Leningrad State University, Faculty of Oriental Studies, Department of Far Eastern History Bachelor with Honors in Japanese History Thesis title: Liberal Ideas in Early Modern Japan 1972.11 -1976.11 Soviet (Russian) Academy of Science Institute of Oriental Studies, Ph.D. student Ph.D. in History, 19/09/1979 Dissertation title: The Movement for Freedom and Popular Rights in Japan: History and Ideology (1870s and 1880s) Employment Record 1972.02 – 1993.01 Junior Researcher, Researcher, Senior Researcher, Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Science, St. Petersburg, Russia 1982.09 -1988.06 Part-time Lecturer, Faculty of Oriental Studies, Leningrad State University, Soviet Union 1993.02 – 1996.03 Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Asian and International Studies, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia 1996.04 – 1998.03 Faculty of International Studies, Hiroshima City University, Japan, Associate Professor 1998.04 – 2013.03 Faculty of International Studies, Graduate School of International Studies, Hiroshima City University, Japan, Professor 2010.04 – present Osaka University, Faculty of Foreign Languages, Part-time Lecturer 2013.06—2013.07 Department of European History and Culture,Heidelberg University, Germany, Visiting Scholar Fellowships and Grants Received: Japan Foundation Fellowship, 1983, Topic of research: Motoori Norinaga: His Life and Ideas. Canon Foundation in Europe Fellowship, 1992-1993. Topic of research: The Interrelation Between Confucianism and Shinto in Tokugawa Japan. 148 Erwin-von-Baelz Guest Professorship, Tuebingen University, Germany, November 1992, lectures and workshops for students on Intellectual History of Tokugawa and Meiji Japan. -

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi No Kumi (Confraria De Misericórdia)

The Jesuit Mission and Jihi no Kumi (Confraria de Misericórdia) Takashi GONOI Professor Emeritus, University of Tokyo Introduction During the 80-year period starting when the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier and his party arrived in Kagoshima in August of 1549 and propagated their Christian teachings until the early 1630s, it is estimated that a total of 760,000 Japanese converted to Chris- tianity. Followers of Christianity were called “kirishitan” in Japanese from the Portu- guese christão. As of January 1614, when the Tokugawa shogunate enacted its prohibi- tion of the religion, kirishitan are estimated to have been 370,000. This corresponds to 2.2% of the estimated population of 17 million of the time (the number of Christians in Japan today is estimated at around 1.1 million with Roman Catholics and Protestants combined, amounting to 0.9% of total population of 127 million). In November 1614, 99 missionaries were expelled from Japan. This was about two-thirds of the total number in the country. The 45 missionaries who stayed behind in hiding engaged in religious in- struction of the remaining kirishitan. The small number of missionaries was assisted by brotherhoods and sodalities, which acted in the missionaries’ place to provide care and guidance to the various kirishitan communities in different parts of Japan. During the two and a half centuries of harsh prohibition of Christianity, the confraria (“brother- hood”, translated as “kumi” in Japanese) played a major role in maintaining the faith of the hidden kirishitan. An overview of the state of the kirishitan faith in premodern Japan will be given in terms of the process of formation of that faith, its actual condition, and the activities of the confraria. -

Matthew P. Funaiole Phd Thesis

HISTORY AND HIERARCHY THE FOREIGN POLICY EVOLUTION OF MODERN JAPAN Matthew P. Funaiole A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/5843 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence History and Hierarchy The Foreign Policy Evolution of Modern Japan This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Saint Andrews by Matthew P. Funaiole 27 October 2014 Word Count: 79,419 iii Abstract This thesis examines the foreign policy evolution of Japan from the time of its modernization during the mid-nineteenth century though the present. It is argued that infringements upon Japanese sovereignty and geopolitical vulnerabilities have conditioned Japanese leaders towards power seeking policy obJectives. The core variables of statehood, namely power and sovereignty, and the perception of state elites are traced over this broad time period to provide a historical foundation for framing contemporary analyses of Japanese foreign policy. To facilitate this research, a unique framework that accounts for both the foreign policy preferences of Japanese leaders and the external constraints of the international system is developed. Neoclassical realist understandings of self-help and relative power distributions form the basis of the presented analysis, while constructivism offers crucial insights into ideational factors that influence state elites. -

Re-Assessing the Global Impact of the Russo-Japanese War 1904-05 第0

Volume 10 | Issue 21 | Number 2 | Article ID 3755 | May 19, 2012 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus World War Zero? Re-assessing the Global Impact of the Russo-Japanese War 1904-05 第0次世界大戦?1904− 1905年日露戦争の世界的影響を再評価する Gerhard Krebs World War Zero? Re-assessing the Global and Yokote Shinji, eds.,The Russo-Japanese Impact of the Russo-Japanese WarWar in Global Perspective: World War Zero. 1904-05 Bd,1, Leiden: Brill 2005. (History of Warfare, Vol. 29) (hereafter: Steinberg). Gerhard Krebs David Wolff, Steven B. Marks, Bruce W. Menning, David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, John W. Steinberg and Yokote Shinji, eds., On the occasion of its centennial, the Russo- The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: Japanese War drew great attention among World War Zero. Vol. 2, Ibid. 2007. (History of historians who organized many symposia and Warfare, Vol. 40) (hereafter: Wolff). published numerous studies. What have been the recent perspectives, debates and insights Maik Hendrik Sprotte, Wolfgang Seifert and on the historical impact of the Russo-Japanese Heinz-Dietrich Löwe, ed.,Der Russisch- War on the imperial world order, evolution of Japanische Krieg 1904/ 05. Anbruch einer international society, and global intellectual neuen Zeit? Wiesbaden, Harassowitz Verlag history? Gerhard Krebs provides 2007.a (hereafter: Sprotte). comprehensive historiographical essay introducing the major works published in the Rotem Kowner, ed., The Impact of the Russo- last ten years on the world-historical impact of Japanese War. London and New York: the Russo-Japanese War, including works in Routledge 2007. (Routledge Studies in the Japanese, Russian, English and German. Modern History of Asia, Vol. -

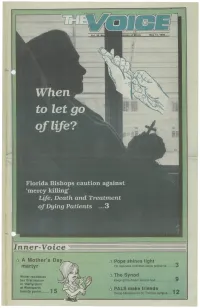

When to Let Go of Life?

Vol.36 Noj locese of Miami Mav 12. 1989 When to let go of life? Florida Bishops caution against 'mercy killing1 Life, Death and Treatment of Dying Patients . • • 3 Inner-Voice A A Mother's Day A Pope shines light martyr On darkness of African social problems O Writer recollects A The Synod her first lesson Keeping the dream alive is next *7 in 'martyrdom' at Woolworth A PALS make friends beauty parlor 15 Group blossoms on St. Thomas campus I dL World / NatiQtia mmmsig- National: U.S. bishops lend support to Panama peace efforts WASHINGTON (NC) — The head of the U.S. bishops' conference has expressed support for the Panamanian bishops' efforts on behalf of a peaceful solution to conflicts in their country. Four days be- fore the May 7 Panamanian elections, Archbishop Nun John L. May of St. Louis, president of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, wrote the head of arrested the Panamanian bishops to commend an April 5 pastoral letter they issued for "upholding, the values Police officers of true democracy and justice." "I hope and pray in Livonia, that its wise counsel will be seriously considered and Mich., drag widely accepted," Archbishop May wrote to Bishop away a nun Jose Dimas Cedeno Delgado of Santiago de Vara- guas, head of the Panamanian bishops' conference. who was arrested in i California Catholics plan benefits abortion to help fund AIDS research protest. The SAN FRANCISCO (NC) — A major rock concert, nun declined other musical events and a telethon are among spring to give her activities which will benefit a San Francisco arch- name when diocesan program for people with AIDS or AIDS- asked. -

Miyagi Prefecture Is Blessed with an Abundance of Natural Beauty and Numerous Historic Sites. Its Capital, Sendai, Boasts a Popu

MIYAGI ACCESS & DATA Obihiro Shin chitose Domestic and International Air Routes Tomakomai Railway Routes Oshamanbe in the Tohoku Region Muroran Shinkansen (bullet train) Local train Shin Hakodate Sapporo (New Chitose) Ōminato Miyagi Prefecture is blessed with an abundance of natural beauty and Beijing Dalian numerous historic sites. Its capital, Sendai, boasts a population of over a million people and is Sendai仙台空港 Sendai Airport Seoul Airport Shin- filled with vitality and passion. Miyagi’s major attractions are introduced here. Komatsu Aomori Aomori Narita Izumo Hirosaki Nagoya(Chubu) Fukuoka Hiroshima Hachinohe Osaka(Itami) Shanghai Ōdate Osaka(kansai) Kuji Kobe Okinawa(Naha) Oga Taipei kansen Akita Morioka Honolulu Akita Shin Miyako Ōmagari Hanamaki Kamaishi Yokote Kitakami Guam Bangkok to the port of Hokkaido Sakata Ichinoseki (Tomakomai) Shinjō Naruko Yamagata Shinkansen Ishinomaki Matsushima International Murakami Yamagata Sendai Port of Sendai Domestic Approx. ShiroishiZaō Niigata Yonezawa 90minutes Fukushima (fastest train) from Tokyo to Sendai Aizu- Tohoku on the Tohoku wakamatsu Shinkansen Shinkansen Nagaoka Kōriyama Kashiwazaki to the port of Nagoya Sendai's Climate Naoetsu Echigo Iwaki (℃)( F) yuzawa (mm) 30 120 Joetsu Shinkansen Nikko Precipitation 200 Temperature Nagano Utsunomiya Shinkansen Maebashi 20 90 Mito Takasaki 100 10 60 Omiya Tokyo 0 30 Chiba 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Publication Date : December 2019 Publisher : Asia Promotion Division, Miyagi Prefectural Government Address : 3-8-1 Honcho, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi -

Texto Completo

DE PUEBLA A SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA: MÁS NOTICIAS SOBRE EL BEATO SEBASTIÁN DE APARICIO, EL FRAILE CARRETERO De Puebla a Santiago de Compostela: más noticias sobre el beato Sebastián de Aparicio, el fraile carretero CARMEN MANSO PORTO* Biblioteca de la Real Academia de la Historia Sumario Se ofrecen nuevas aportaciones a la biografía y representaciones artísticas de Sebastián de Aparicio en relación con el proceso de su beatificación, que completan el trabajo publicado en 2018 en esta misma Revista1. Abstract New contributions to the biography and artistic representations of Sebastián de Aparicio are offered in relation to the process of his beatification, which complete the work published in 2018 in this same Magazine. l beato Sebastián de Aparicio (A Gudiña-Ourense, 20-01-1502 / Puebla de Elos Ángeles, 25-02-1600) dejó una importante huella en el virreinato de Nueva España. Como agricultor y constructor de carretas, contribuyó a la mejora de las condiciones de trabajo de los indios en el campo y en las minas. El duro acarreo de las mercancías en recuas de mulas y a hombros de los indios tamemes, dio pasó a su transporte en carretas arrastradas por yuntas de bueyes. Durante los últimos veintidós años de su vida, Aparicio ejerció el oficio de fraile limosnero en el convento franciscano de Puebla de los Ángeles y trabajó como carretero recogiendo alimentos y enseres para la comunidad. Su fama de santidad y de trabajador infatigable al servicio de los pobres se extendió por toda la zona. Falleció al mes de haber cumplido los 98 años. Su cadáver amortajado fue velado y, desde entonces, comenzaron los relatos de sus milagros. -

Pacific Partners: Forging the US-Japan Special Relationship

Pacific Partners: Forging the U.S.-Japan Special Relationship 太平洋のパートナー:アメリカと日本の特別な関係の構築 Arthur Herman December 2017 Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Research Report Pacific Partners: Forging the U.S.-Japan Special Relationship 太平洋のパートナー:アメリカと日本の特別な関係の構築 Arthur Herman Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute © 2017 Hudson Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. For more information about obtaining additional copies of this or other Hudson Institute publications, please visit Hudson’s website, www.hudson.org Hudson is grateful for the support of the Smith Richardson Foundation in funding the research and completion of this report. ABOUT HUDSON INSTITUTE Hudson Institute is a research organization promoting American leadership and global engagement for a secure, free, and prosperous future. Founded in 1961 by strategist Herman Kahn, Hudson Institute challenges conventional thinking and helps manage strategic transitions to the future through interdisciplinary studies in defense, international relations, economics, health care, technology, culture, and law. Hudson seeks to guide public policy makers and global leaders in government and business through a vigorous program of publications, conferences, policy briefings and recommendations. Visit www.hudson.org for more information. Hudson Institute 1201 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20004 P: 202.974.2400 [email protected] www.hudson.org Table of Contents Introduction (イントロダクション) 3 Part I: “Allies of a Kind”: The US-UK Special Relationship in 15 Retrospect(パート I:「同盟の一形態」:米英の特別な関係は過去どうだったの -

La Embajada Keicho- (1613 - 1620)

La Embajada Keicho- (1613 - 1620) Tutorizado por el profesor Sean Golden Jonathan López-Vera Introducción Graduado en Estudios de Asia Oriental (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), estudiante de máster en Historia del El periodo de los siglos XV a XVII es, sin duda, un mo- Mundo (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), mento de grandes y decisivos cambios, sobre todo editor y fundador de Asiadémica y en Europa, donde se producen numerosos avances autor de la web HistoriaJaponesa.com en campos como el de las ciencias, de la filosofía, del arte e incluso de la religión, esta última hasta ese Interesado principalmente en momento reacia a cualquier movimiento. En el te- la Historia Premoderna de Japón rreno de lo práctico, Europa se lanza en esta época a conocer el resto del planeta, hasta entonces un completo misterio pero, en menos de un siglo, circunnavegado y en gran parte cartografiado. Se ponen en contacto culturas desconocidas o semi- desconocidas, aunque no siempre de la manera más pacífica y cordial, y las personas, las mercan- cías y, sobre todo, el conocimiento se desplazan de una punta a la otra del planeta. Podríamos decir perfectamente que el fenómeno de la globalización, aunque parezca algo muy nuevo, empezó ya en esta época. Este trabajo se centra en uno de estos viajes, aunque se trata de uno que funciona en sentido in- verso a los que estábamos comentando, pues esta vez son los supuestamente descubiertos los que viajan a descubrir a sus descubridores, lo que otorga a esta aventura un carácter peculiarmente in- teresante. Relatar este viaje, además, resulta especialmente útil para dibujar una imagen del Japón de la época, un país que no puede escapar, en ningún nivel, del complicado contexto en el que se encuentra. -

Shrines of Mexico Spiritual Director: Fr. Ron Schock November 28 - December 4, 2018

Shrines of Mexico Spiritual Director: Fr. Ron Schock November 28 - December 4, 2018 Day 1 - Nov 28: Depart from DTW for your flight to Mexico City. Upon arrival, transfer to the city of Puebla, “The City of the Angels.” We will stay at a colonial hotel in downtown, close to churches, restaurants, and shops. (D) Day 2 - Nov 29: Puebla - After breakfast, Mass at the Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary in the Church of Santo Domingo, continuing to the Cathedral and the church of St. Francis of Assisi to view the body of Blessed Sebastian de Aparicio whose body remains incorrupt until today. Lunch will be served at a local restaurant followed by some time to shop in El Parian, a handcraft market where it is possible to find Puebla’s famous Talavera pottery. (B, L) Day 3 - Nov 30: Tlaxcala - After breakfast, we will visit the Shrine of San Miguel del Milagro, site of St. Michael’s apparition to Diego Lazaro, in Tlaxcala. Mass will be held at the Shrine of Our Lady of Ocotlan where Our Lady appeared to Juan Diego Bernardino in 1541. In colonial times, they used open chapels to teach the indigenous peoples the Holy Mass. It is a real treat to be able to visit one of the most beautiful open-chapels in the country! Lunch will be served at a local restaurant prior to departing for Mexico City to check in at our centrally-located hotel. (B, L) $2,249.00 per person, Cash/Check Day 4 - Dec 1: Mexico City - On the way to the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, discount, double occupancy. -

Was the Russo-Japanese War World War Zero?

RE-IMAGINING CULTURE IN THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR Was the Russo-Japanese War World War Zero? JOHN W. STEINBERG As with any war in history, the Russo-Japanese War enjoys its share of myths and legends that range from Admiral Alekseev’s barber being a Japanese spy to the saga of the Baltic Fleet becoming the “fleet that had to die.” Perhaps because of such legends, or perhaps because World War I broke out less than a decade after the Russo-Japanese War formally ended with the Treaty of Portsmouth in 1905, the centennial anniversary of Japan’s stunning victory witnessed a resurgence in Russo-Japanese War studies. Scholars from around the world responded to this date by convening various seminars, workshops, and conferences to reopen the study of a conflict that, while never completely forgotten, was largely overlooked after World War I. Always considered a bilateral engagement between two military powers, which it was in its most basic sense, the aim of all of these scholarly endeavors was to broaden our understanding of not only the war but also its global impact. The three following articles represent the work of one of the first such intellectual endeavors, a conference on “Re-imagining Culture in the Russo-Japanese War” that was held at Birkbeck College in London in March 2004.1 By addressing the impact of the conflict on society from its art and literature to the public reaction to the war as it progressed, Naoko Shimazu, Rosamund Bartlett, and David Crowley exhibit the depth of engagement that existed at every level of the civil-military nexus. -

Japanese Miscommunication with Foreigners

Japanese Miscommunication with Foreigners JAPANESE MISCOMMUNICATION WITH FOREIGNERS IN SEARCH FOR VALID ACCOUNTS AND EFFECTIVE REMEDIES Rotem Kowner Abstract: Numerous personal accounts, anecdotal stories, and surveys suggest that for many Japanese communication with foreigners is a difficult and even unpleas- ant experience. This intercultural miscommunication, which seems to characterize Japanese more than their foreign counterparts, has attracted the attention of schol- ars, both in Japan and overseas. In fact, ever since the forced opening of Japan 150 years ago, scholars and laymen have advanced explicit and implicit theories to ac- count for the presumed Japanese “foreigner complex” and its effect on Japanese in- tercultural communication. These theories focus on Japan’s geographical and his- torical isolation, linguistic barriers, idiosyncratic communication style, and the interpersonal shyness of its people. While there is a certain kernel of truth in many of the hypotheses proposed, they tend to exaggerate cultural differences and stress marginal aspects. This article seeks to review critically the different views of Japa- nese communication difficulties with foreigners, and to advance complementary hypotheses based on recent studies. It also attempts to examine the implications of this miscommunication and to consider several options to alleviate it. INTRODUCTION Two meetings held in the last decade between Japan’s leading politicians and the American president Bill Clinton highlight the issue of intercultural miscommunication – an important but somewhat neglected aspect of hu- man communication. Like members of any culture, Americans have their share of intercultural miscommunication, yet this article concerns the Jap- anese side. Our first case in point is the former prime minister Mori Yoshirô, whose English proficiency was limited, to the say the least.