Jazz by Jeffrey Escoffier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mesia Austin, Percussion Received Much of the Recognition Due a Venerable Jazz Icon

and Blo win' The Blues Away (1959), which includes his famous, "Sister Sadie." He also combined jazz with a sassy take on pop through the 1961 hit, "Filthy McNasty." As social and cultural upheavals shook the nation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Silver responded to these changes through music. He commented directly on the new scene through a trio of records called United States of Mind (1970-1972) that featured the spirited vocals of Andy Bey. The composer got deeper into cosmic philosophy as his group, Silver 'N Strings, recorded Silver 'N Strings School of Music Play The Music of the Spheres (1979). After Silver's long tenure with Blue Note ended, he continued to presents create vital music. The 1985 album, Continuity of Spirit (Silveto), features his unique orchestral collaborations. In the 1990s, Silver directly answered the urban popular music that had been largely built from his influence on It's Got To Be Funky (Columbia, 1993). On Jazz Has A Sense of Humor (Verve, 1998), he shows his younger SENIOR RECITAL group of sidemen the true meaning of the music. Now living surrounded by a devoted family in California, Silver has Mesia Austin, percussion received much of the recognition due a venerable jazz icon. In 2005, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) gave him its President's Merit Award. Silver is also anxious to tell the Theresa Stephens, clarinet Brian Palat, percussion world his life story in his own words as he just released his autobiography, Let's Get To The Nitty Gritty. -

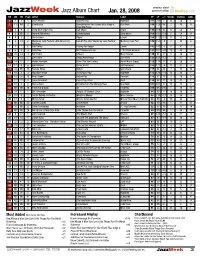

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 28, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Steve Nelson Sound-Effect HighNote 211 210 1 13 56 1 2 11 NR 2 Eliane Elias Something For You: Eliane Elias Sings & Blue Note 196 128 68 2 49 14 Plays Bill Evans 3 5 9 2 Deep Blue Organ Trio Folk Music Origin 194 169 25 15 52 1 4 2 NR 2 Hendrik Meurkens Sambatropolis Zoho Music 166 185 -19 2 54 13 5 4 2 2 Jim Snidero Tippin’ Savant 154 172 -18 11 53 1 6 6 33 6 Monterey Jazz Festival 50th Aniversary Live At The 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival Monterey Jazz Fest 145 154 -9 3 43 8 All-Stars 7 7 7 6 Bob DeVos Playing For Keeps Savant 142 145 -3 11 47 0 8 3 5 3 Andy Bey Ain’t Necessarily So 12th Street Records 137 182 -45 10 49 0 9 20 34 9 Ron Blake Shayari Mack Avenue 136 94 42 3 46 11 10 7 14 7 Joe Locke Sticks And Strings Jazz Eyes 132 145 -13 7 37 5 11 14 11 2 Herbie Hancock River: The Joni Letters Verve Music Group 125 114 11 17 50 0 12 12 8 8 John Brown Terms Of Art Self Released 123 127 -4 11 32 0 13 28 NR 13 Pamela Hines Return Spice Rack 117 84 33 2 43 14 14 10 3 3 Houston Person Thinking Of You HighNote 115 139 -24 13 38 2 15 18 38 15 Brad Goode Nature Boy Delmark 112 97 15 3 29 6 16 22 21 3 Cyrus Chestnut Cyrus Plays Elvis Koch 110 93 17 16 37 1 17 16 6 6 Stacey Kent Breakfast On The Morning Tram Blue Note 101 101 0 16 33 0 18 NR NR 18 Frank Kimbrough Air Palmetto 100 NR 100 1 36 31 19 24 11 1 Eric Alexander Temple Of Olympic Zeus HighNote 94 90 4 18 39 0 20 15 4 2 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Monterey -

Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: a Pedagogical Study

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-2019 Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study Lara Marie Moline Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Moline, Lara Marie, "Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study" (2019). Dissertations. 576. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/576 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 LARA MARIE MOLINE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School VOCAL JAZZ IN THE CHORAL CLASSROOM: A PEDAGOGICAL STUDY A DIssertatIon SubMItted In PartIal FulfIllment Of the RequIrements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Lara Marie MolIne College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music May 2019 ThIs DIssertatIon by: Lara Marie MolIne EntItled: Vocal Jazz in the Choral Classroom: A Pedagogical Study has been approved as meetIng the requIrement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of VIsual and Performing Arts In School of Music, Program of Choral ConductIng Accepted by the Doctoral CoMMIttee _________________________________________________ Galen Darrough D.M.A., ChaIr _________________________________________________ Jill Burgett D.A., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Oravitz Ph.D., CoMMIttee Member _________________________________________________ Michael Welsh Ph.D., Faculty RepresentatIve Date of DIssertatIon Defense________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School ________________________________________________________ LInda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and InternatIonal AdMIssions Research and Sponsored Projects ABSTRACT MolIne, Lara Marie. -

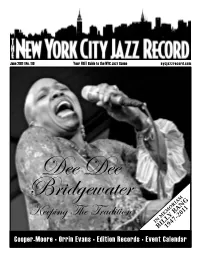

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

SUS Ad for 2011 1

The Foundation for Music Education is announcing the 7th annual summer “Stars Under The Stars,” featuring the Brad Leali Quartet with Brad Leali on Saxophone, Claus Raible on piano, Giorgos Antiniou on bass, Alvester Garnett on drums, and joined by vocalist Martha Burks. The event will be on Friday, August 12, 2011 from 7:00 to 10:00 PM at the Louise Underwood Center. “Stars Under the Stars” is an evening concert benefitting music scholarships that will include an hour of socializing with sensational food and drink from “Stella’s.” The event benefits music education scholarships. Our traditional guest host and emcee will be local TV and Radio personality Jeff Klotzman. The “Stars” this year are brilliant world-class jazz artists from the United States, Greece, and Germany! For information about tickets and/or making donations for “Stars Under the Stars,” please call 806- 687-0861, 806-300-2474, and www.foundationformusiceducation.org. Information - The Quartet is captivating through the spontaneity and homogeneousness of the performance as well as with the communicative, non-verbal interaction of the four musicians. The band book consists, besides grand jazz classics, mainly of original compositions by the members. BRAD LEALI Saxophone http://www.bradleali.com/ CLAUS RAIBLE Piano, compositions and arrangements http://www.clausraible.com/Projects.htm GIORGIOS ANTONIOU Bass http://www.norwichjazzparty.com/Musician.asp?ID=22 ALVESTER GARNETT Drums http://www.alvestergarnett.com/ MARTHA BURKS Vocalist http://www.marthaburks.com/ Some comments about the quartet in the press: “This quartet enchanted the audience from the first, almost explosion like saxophone note and put them under their spell .. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Ira Gershwin

Late Night Jazz – Ira Gershwin Samstag, 15. September 2018 22.05 – 24.00 SRF 2 Kultur Der ältere Bruder des Jahrhundertkomponisten George Gershwin (1898 – 1937) verschwindet hinter dem Genie des jüngeren Gershwin zuweilen etwas. Dabei lieferte er kongeniale Texte zu George Gershwin’s Melodien, zum Beispiel für die Oper «Porgy and Bess». Und nach dem frühen Tod des Bruders arbeitete Ira noch fast fünfzig Jahre weiter. Er schrieb Songtexte zu Melodien von Harold Arlen, Jerome Kern und Kurt Weill, die von Stars wie Barbra Streisand oder Frank Sinatra gesungen wurden. Redaktion: Beat Blaser Moderation: Annina Salis Sonny Stitt - Verve Jazz Masters 50 (1959) Label: Verve Track 01: I Got Rhythm Judy Garland - A Star Is Born (1954) Label: Columbia Track 03: Gotta Have Me Go with You Benny Goodman Sextet - Slipped Disc 1945 – 1946 (1945) Label: CBS Track 12: Liza Cab Calloway and His Orchestra - 1942-1947 (1945) Label: Classics Records Track 07: All at Once Ira Gershwin & Kurt Weill - Tryout. A series of private rehearsal recordings (1945) Label: DRG Track 07: Manhattan (Indian Song) Oscar Peterson Trio - The Gershwin Songbooks (1952) Label: Verve Track 06: Oh, Lady Be Good Ella Fitzgerald - Get happy! (1959) Label: Verve Track 02: Cheerful Little Earful Artie Shaw - In the Beginning (1936) Label: HEP Records Track 03: I Used to Be Above Love Stan Getz - West Coast Jazz (1955) Label: Verve Track 08: Of Thee I Sing Judy Garland - A star is born (1954) Label: Columbia Track 16: Here's What I'm Here For The Four Freshmen - The Complete Capitol Four -

Comin' out Swingin' Symposium & Concerts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESENTS symposium & concerts Comin’ out swingin’ Provoke Thinking About Sexuality in Music November 16 & 17 At UBC and The Ironworks Vancouver, B.C. - Coastal Jazz and Blues Society is pleased to announce Comin’ Out Swingin’: Sexualities in Improvisation, the first symposium of its kind in Western Canada. The symposium is presented in partnership with the Department of English at the University of British Columbia, St. John’s College UBC, and “Improvisation, Community, and Social Practice,” a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Major Collaborative Research Initiative. The events will take place November 16-17, 2007 from 9 am to 5 pm at St. John’s College Lounge. Improvised and creative new musics have been on the upswing in recent years, but listeners, critics, and scholars have said little, so far, about the relationships of the various forms and practices of improvisation to gender and sexuality. Compositions and performances in recent years by such prominent artists as Marilyn Lerner, Fred Hersch, Patricia Barber, Irene Schweizer, Maggie Nicols, Gary Burton, Pauline Oliveros, Lori Freedman, Steve Lacy and Irene Aebi, Miya Masaoka, Evan Parker, Peter Brötzmann, and many others have placed the cultural politics of gender directly at issue, while many recorded works from the history of improvised music and jazz (from Valaida Snow to Cecil Taylor, from Billy Strayhorn to Andy Bey) provoke a reconsideration of the music’s relationship to sexuality and identity. With an ear to addressing this gap, Comin’ Out Swingin’ will provoke, challenge, and inspire discussion and exploration of sexuality in music and other forms of improvisation. -

Orrinevans EPK 0626 REV2.Pdf

...It Was Beauty …a poised artist with an impressive template of ideas at his command. – New York Times Pianist Orrin Evans released his 20th recording “…It Was Beauty ” on Criss Cross which debuted the music on May 27th @ Blue Note, NYC ••• A Prodigious Producer, Evans Also Launched Likemind Collective With New CDs by Tarbaby, Eric Revis and JD Walter Two time Grammy nominee and Pew Fellow, Orrin Evans has been recognized as one of the most distinctive and inventive pianists of his generation. In a short span of time Orrin has earned the titles of pianist, composer, bandleader, teacher, producer and arranger. The New York Times described the pianist as "... a poised artist with an impressive template of ideas at his command", a quality that has undoubtedly assisted in keeping Orrin at the forefront of the music scene. The latest release by Evans, “It Was Beauty” marks his 20th recording as a leader and his seventh release for the label, Criss Cross, which he began recording for at age 21. In his 20-year plus career, he’s been critically acclaimed for his imposing chops, his propulsive take on rhythm and harmony alike. Over- looked has been the beauty he creates through his art form. For the project, Evans convened four bassists – Eric Revis, Ben Wolfe, Luques Curtis, and Alex Claffy – and drummer Donald Edwards, all bandstand partners in recent years. Brian McKenna ph: 917.748.4337 P.O. Box 88 Pomona, NY 10970 [email protected] ...It Was Beauty Likemind. Evans has a restless mind as an artist, producer and bandmate, compelling him to forge new paths for himself and artists of likemind. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

A Transgender Journey in Three Acts a PROJECT SUBMITTED to THE

Changes in Time: A Transgender Journey in Three Acts A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ethan Bryce Boatner IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2012 © Ethan Bryce Boatner 2012 i For Carl and Garé, Josephine B, Jimmy, Timothy, Charles, Greg, Jan – and all the rest of you – for your confidence and unstinting support, from both EBBs. ii BAH! Kid talk! No man is poor who can to what he likes to do once in a while! Scrooge McDuck ~ Only a Poor Old Man iii CONTENTS Chapter By Way of Introduction: On Being and Becoming ..…………………………………………1 1 – There Have Always Been Transgenders–Haven’t There? …………………………….8 2 – The Nosology of Transgenderism, or, What’s Up, Doc? …….………...………….….17 3 – And the Word Was Transgender: Trans in Print, Film, Theatre ………………….….26 4 – The Child Is Father to the Man: Life As Realization ………….…………...……....….32 5 – Smell of the Greasepaint, Roar of the Crowd ……………………………...…….……43 6 – Curtain Call …………………………………………………………………....………… 49 7 – Program ..………………………..……………………………….……………...………..54 8 – Changes in Time ....………………………..…………………….………..….……........59 Wishes ……………………………….………………….……………...…………………60 Dresses …………………………………………………….…………………….….…….85 Changes ………………………………………………………….….………..…………107 9 – Works Cited …………………….………………………………………....…………….131 1 By Way of Introduction On Being and Becoming “I think you’re very brave,” said G as the date for my public play-reading approached. “Why?” I asked. “It takes guts to come out like that, putting all your personal things out in front of everybody,” he replied. “Oh no,” I assured him. “The first six decades took guts–this is a piece of cake.” In fact, I had not embarked on the University of Minnesota’s Master of Liberal Studies (MLS) program with the intention of writing plays. -

2012 Hanne-Blank-Straight.Pdf

STRAIGHT THE SURPRISINGLY SHORT HISTORY OF HETEROSEXUALITY HANNE BLANK Beacon Press · Boston 2 For Malcolm 3 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Sexual Disorientation CHAPTER ONE The Love That Could Not Speak Its Name CHAPTER TWO Carnal Knowledge CHAPTER THREE Straight Science CHAPTER FOUR The Marrying Type CHAPTER FIVE What’s Love Got to Do with It? CHAPTER SIX The Pleasure Principle CHAPTER SEVEN Here There Be Dragons ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX 4 INTRODUCTION Sexual Disorientation Every time I go to the doctor, I end up questioning my sexual orientation. On some of its forms, the clinic I visit includes five little boxes, a small matter of demographic bookkeeping. Next to the boxes are the options “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual,” “transgender,” or “heterosexual.” You’re supposed to check one. You might not think this would pose a difficulty. I am a fairly garden-variety female human being, after all, and I am in a long-term monogamous relationship, well into our second decade together, with someone who has male genitalia. But does this make us, or our relationship, straight? This turns out to be a good question, because there is more to my relationship—and much, much more to heterosexuality—than easily meets the eye. There’s biology, for one thing. My partner was diagnosed male at birth because he was born with, and indeed still has, a fully functioning penis. But, as the ancient Romans used to say, barba non facit philosophum—a beard does not make one a philosopher. Neither does having a genital outie necessarily make one male. Indeed, of the two sex chromosomes—XY—which would be found in the genes of a typical male, and XX, which is the hallmark of the genetically typical female—my partner’s DNA has all three: XXY, a pattern that is simultaneously male, female, and neither.