Teaching Jazz As American Culture Lesson Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Annie Ross Uk £3.25

ISSUE 162 SUMMER 2020 ANNIE ROSS UK £3.25 Photo by Merlin Daleman CONTENTS Photo by Merlin Daleman ANNIE ROSS (1930-2020) The great British-born jazz singer remembered by VAL WISEMAN and DIGBY FAIRWEATHER (pages 12-13) THE 36TH BIRMINGHAM, SANDWELL 4 NEWS & WESTSIDE JAZZ FESTIVAL Birmingham Festival/TJCUK OCTOBER 16TH TO 25TH 2020 7 WHAT I DID IN LOCKDOWN [POSTPONED FROM ORIGINAL JULY DATES] Musicians, promoters, writers 14 ED AND ELVIN JAZZ · BLUES · BEBOP · SWING Bicknell remembers Jones AND MORE 16 SETTING THE STANDARD CALLUM AU on his recent album LIVE AND ROCKING 18 60-PLUS YEARS OF JAZZ MORE THAN 90% FREE ADMISSION BRIAN DEE looks back 20 THE V-DISC STORY Told by SCOTT YANOW 22 THE LAST WHOOPEE! Celebrating the last of the comedy jazz bands 24 IT’S TRAD, GRANDAD! ANDREW LIDDLE on the Bible of Trad FIND US ON FACEBOOK 26 I GET A KICK... The Jazz Rag now has its own Facebook page. with PAOLO FORNARA of the Jim Dandies For news of upcoming festivals, gigs and releases, features from the archives, competitions and who 26 REVIEWS knows what else, be sure to ‘like’ us. To find the Live/digital/ CDs page, simply enter ‘The Jazz Rag’ in the search bar at the top when logged into Facebook. For more information and to join our mailing list, visit: THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 BRITISH JAZZ AWARDS CANCELLED WWW.BIRMINGHAMJAZZFESTIVAL.COM Fax: 0121 454 9996 Email: [email protected] This is the time of year when Jazz Rag readers expect to have the opportunity to vote for the Jazz Oscars, the British Jazz Awards. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Mesia Austin, Percussion Received Much of the Recognition Due a Venerable Jazz Icon

and Blo win' The Blues Away (1959), which includes his famous, "Sister Sadie." He also combined jazz with a sassy take on pop through the 1961 hit, "Filthy McNasty." As social and cultural upheavals shook the nation during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Silver responded to these changes through music. He commented directly on the new scene through a trio of records called United States of Mind (1970-1972) that featured the spirited vocals of Andy Bey. The composer got deeper into cosmic philosophy as his group, Silver 'N Strings, recorded Silver 'N Strings School of Music Play The Music of the Spheres (1979). After Silver's long tenure with Blue Note ended, he continued to presents create vital music. The 1985 album, Continuity of Spirit (Silveto), features his unique orchestral collaborations. In the 1990s, Silver directly answered the urban popular music that had been largely built from his influence on It's Got To Be Funky (Columbia, 1993). On Jazz Has A Sense of Humor (Verve, 1998), he shows his younger SENIOR RECITAL group of sidemen the true meaning of the music. Now living surrounded by a devoted family in California, Silver has Mesia Austin, percussion received much of the recognition due a venerable jazz icon. In 2005, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (NARAS) gave him its President's Merit Award. Silver is also anxious to tell the Theresa Stephens, clarinet Brian Palat, percussion world his life story in his own words as he just released his autobiography, Let's Get To The Nitty Gritty. -

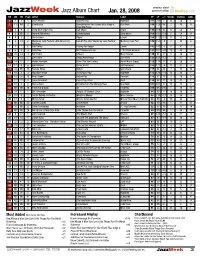

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 28, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Steve Nelson Sound-Effect HighNote 211 210 1 13 56 1 2 11 NR 2 Eliane Elias Something For You: Eliane Elias Sings & Blue Note 196 128 68 2 49 14 Plays Bill Evans 3 5 9 2 Deep Blue Organ Trio Folk Music Origin 194 169 25 15 52 1 4 2 NR 2 Hendrik Meurkens Sambatropolis Zoho Music 166 185 -19 2 54 13 5 4 2 2 Jim Snidero Tippin’ Savant 154 172 -18 11 53 1 6 6 33 6 Monterey Jazz Festival 50th Aniversary Live At The 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival Monterey Jazz Fest 145 154 -9 3 43 8 All-Stars 7 7 7 6 Bob DeVos Playing For Keeps Savant 142 145 -3 11 47 0 8 3 5 3 Andy Bey Ain’t Necessarily So 12th Street Records 137 182 -45 10 49 0 9 20 34 9 Ron Blake Shayari Mack Avenue 136 94 42 3 46 11 10 7 14 7 Joe Locke Sticks And Strings Jazz Eyes 132 145 -13 7 37 5 11 14 11 2 Herbie Hancock River: The Joni Letters Verve Music Group 125 114 11 17 50 0 12 12 8 8 John Brown Terms Of Art Self Released 123 127 -4 11 32 0 13 28 NR 13 Pamela Hines Return Spice Rack 117 84 33 2 43 14 14 10 3 3 Houston Person Thinking Of You HighNote 115 139 -24 13 38 2 15 18 38 15 Brad Goode Nature Boy Delmark 112 97 15 3 29 6 16 22 21 3 Cyrus Chestnut Cyrus Plays Elvis Koch 110 93 17 16 37 1 17 16 6 6 Stacey Kent Breakfast On The Morning Tram Blue Note 101 101 0 16 33 0 18 NR NR 18 Frank Kimbrough Air Palmetto 100 NR 100 1 36 31 19 24 11 1 Eric Alexander Temple Of Olympic Zeus HighNote 94 90 4 18 39 0 20 15 4 2 Gerald Wilson Orchestra Monterey -

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell Glenn Miller Original release label “Sun Valley Serenade” Though Glenn Miller and His Orchestra’s well-known, robust and swinging hit “In the Mood” was recorded in 1939 (and was written even earlier), it has since come to symbolize the 1940s, World War II, and the entire Big Band Era. Its resounding success—becoming a hit twice, once in 1940 and again in 1943—and its frequent reprisal by other artists has solidified it as a time- traversing classic. Covered innumerable times, “In the Mood” has endured in two versions, its original instrumental (the specific recording added to the Registry in 2004) and a version with lyrics. The music was written (or written down) by Joe Garland, a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith who also composed “Leap Frog” for Les Brown and his band. The lyrics are by Andy Razaf who would also contribute the words to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose.” For as much as it was an original work, “In the Mood” is also an amalgamation, a “mash-up” before the term was coined. It arrived at its creation via the mixture and integration of three or four different riffs from various earlier works. Its earliest elements can be found in “Clarinet Getaway,” from 1925, recorded by Jimmy O’Bryant, an Arkansas bandleader. For his Paramount label instrumental, O’Bryant was part of a four-person ensemble, featuring a clarinet (played by O’Bryant), a piano, coronet and washboard. Five years later, the jazz piece “Tar Paper Stomp” by Joseph “Wingy” Manone, from 1930, beget “In the Mood’s” signature musical phrase. -

Album Covers Through Jazz

SantiagoAlbum LaRochelle Covers Through Jazz Album covers are an essential part to music as nowadays almost any project or single alike will be accompanied by album artwork or some form of artistic direction. This is the reality we live with in today’s digital age but in the age of vinyl this artwork held even more power as the consumer would not only own a physical copy of the music but a 12’’ x 12’’ print of the artwork as well. In the 40’s vinyl was sold in brown paper sleeves with the artists’ name printed in black type. The implementation of artwork on these vinyl encasings coincided with years of progress to be made in the genre as a whole, creating a marriage between the two mediums that is visible in the fact that many of the most acclaimed jazz albums are considered to have the greatest album covers visually as well. One is not responsible for the other but rather, they each amplify and highlight each other, both aspects playing a role in the artistic, musical, and historical success of the album. From Capitol Records’ first artistic director, Alex Steinweiss, and his predecessor S. Neil Fujita, to all artists to be recruited by Blue Note Records’ founder, Alfred Lion, these artists laid the groundwork for the role art plays in music today. Time Out Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita Recorded June 1959 Columbia Records Born in Hawaii to japanese immigrants, Fujita began studying art Dave Brubeck- piano Paul Desmond- alto sax at an early age through his boarding school. -

ELLINGTON '2000 - by Roger Boyes

TH THE INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN22 year of publication OEMSDUKE ELLINGTON MUSIC SOCIETY | FOUNDER: BENNY AASLAND HONORARY MEMBER: FATHER JOHN GARCIA GENSEL As a DEMS member you'll get access from time to time to / jj£*V:Y WL uni < jue Duke material. Please bear in mind that such _ 2000_ 2 material is to be \ handled with care and common sense.lt " AUQUSl ^^ jj# nust: under no circumstances be used for commercial JUriG w «• ; j y i j p u r p o s e s . As a DEMS member please help see to that this Editor : Sjef Hoefsmit ; simple rule is we \&! : T NSSESgf followed. Thus will be able to continue Assisted by: Roger Boyes ^ fueur special offers lil^ W * - DEMS is a non-profit organization, depending on ' J voluntary offered assistance in time and material. ALL FOR THE L O V E D U K E !* O F Sponsors are welcomed. Address: Voort 18b, Meerle. Belgium - Telephone and Fax: +32 3 315 75 83 - E-mail: [email protected] LOS ANGELES ELLINGTON '2000 - By Roger Boyes The eighteenth international conference of the Kenny struck something of a sombre note, observing that Duke Ellington Study Group took place in the we’re all getting older, and urging on us the need for active effort Roosevelt Hotel, 7000 Hollywood Boulevard, Los to attract the younger recruits who will come after us. Angeles, from Wednesday to Sunday, 24-28 May This report isn't the place for pondering the future of either 2000. The Duke Ellington Society of Southern conferences or the wider activities of the Ellington Study Groups California were our hosts, and congratulations are due around the world. -

Bright Moments!

Volume 46 • Issue 6 JUNE 2018 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. On stage at NJPAC performing Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s “Bright Moments” to close the tribute to Dorthaan Kirk on April 28 are (from left) Steve Turre, Mark Gross, musical director Don Braden, Antoinette Montague and Freddy Cole. Photo by Tony Graves. SNEAKING INTO SAN DIEGO BRIGHT MOMENTS! Pianist Donald Vega’s long, sometimes “Dorthaan At 80” Celebrating Newark’s “First harrowing journey from war-torn Nicaragua Lady of Jazz” Dorthaan Kirk with a star-filled gala to a spot in Ron Carter’s Quintet. Schaen concert and tribute at the New Jersey Performing Arts Fox’s interview begins on page 14. Center. Story and Tony Graves’s photos on page 24. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New Jersey Jazz socIety Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Jazz Trivia . 4 Prez sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Change of Address/Support NJJS/ By Cydney Halpin President, NJJS Volunteer/Join NJJs . 43 Crow’s Nest . 44 t is with great delight that I announce Don commitment to jazz, and for keeping the music New/Renewed Members . 45 IBraden has joined the NJJS Board of Directors playing. (Information: www.arborsrecords.com) in an advisory capacity. As well as being a jazz storIes n The April Social at Shanghai Jazz showcased musician of the highest caliber on saxophone and Dorthaan at 80 . cover three generations of musicians, jazz guitar Big Band in the Sky . 8 flute, Don is an award-winning recording artist, virtuosi Gene Bertoncini and Roni Ben-Hur and Memories of Bob Dorough . -

Scripting and Consuming Black Bodies in Hip Hop Music and Pimp Movies

SCRIPTING AND CONSUMING BLACK BODIES IN HIP HOP MUSIC AND PIMP MOVIES Ronald L Jackson II and Sakile K. Camara ... Much of the assault on the soulfulness of African American people has come from a White patriarchal, capitalist-dominated music industry, which essentially uses, with their consent and collusion, Black bodies and voices to be messengers of doom and death. Gangsta rap lets us know Black life is worth nothing, that love does not exist among us, that no education for critical consciousness can save us if we are marked for death, that women's bodies are objects, to be used and discard ed. The tragedy is not that this music exists, that it makes a lot of money, but that there is no countercultural message that is equally powerful, that can capture the hearts and imaginations of young Black folks who want to live, and live soulfully) Feminist film critics maintain that the dominant look in cinema is, historically, a gendered gaze. More precisely, this viewpoint argues that the dominant visual and narrative conventions of filmmaking generally fix "women as image" and "men as bearer of the image." I would like to suggest that Hollywood cinema also frames a highly particularized racial gaze-that is, a representational system that posi tions Blacks as image and Whites as bearer of the image.2 Black bodies have become commodities in the mass media marketplace, particu larly within Hip Hop music and Black film. Within the epigraph above, both hooks and Watkins explain the debilitating effects that accompany pathologized fixations on race and gender in Black popular culture. -

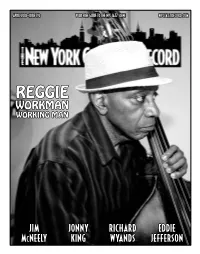

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

“New Negro Movement” Among Jazz Musicians

THE INFLUENCE OF THE “NEW NEGRO MOVEMENT” AMONG JAZZ MUSICIANS A Master’s submitted to the Caspersen School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Letters Advisor: Dr. Robert Butts Vincent Unger Drew University Madison, New Jersey May 2021 © Copyright 2021 Vincent Unger ABSTRACT The Influence of the “New Negro Movement” among Jazz Musicians Vincent Unger The Harlem Renaissance is usually thought of as a literary movement. However, it was much more than that, the Harlem Renaissance was a movement among the arts, music, and literature. The intellectual elite of Harlem saw the Harlem renaissance as new era for the African-American: one where African Americans could rise up from poverty to the middle class, and, shake off the stereotype of the primitive savage. The “New Negro Movement” was started by Alain Locke an W.E.B. Du Bois. Locke would lay the foundation for the movement with his book The New Negro. Du Bois on the other hand, would focus on educating African Americans about their African heritage. While integral to the movement, jazz music would be overlooked by Locke and other leaders of the movement. The New Negro only devotes a single entry to jazz in historian J.A. Roger’s “Jazz At Home.” Musicians Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington and William Grant Still would become an integral part of the “New Negro Movement.” Duke Ellington would make great strides as one of the most popular jazz musicians. William Grant Still would excel as a musician and a composer. These two musicians would pave the way for many young musicians.