WINTER 2003 - Volume 50, Number 4 Wanted!! Young Readers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Flying Ace

020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 1 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 2 This book is your passport into time. Can you survive World War I? Turn the page to find out. 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 3 World War I Flying Ace by Richard Mueller illustrated by George Pratt A Byron Preiss Book 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 4 RL4, IL age 10 and up Copyright © 1988, 2000 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications “Time Machine&rdqup; is a registered trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark office. Book design by Alex Jay Cover painting by Steve Fastner Cover design by Alex Jay Mechanicals by Mary LeCleir An ipicturebooks.com ebook ipicturebooks.com 24 West 25th St., 11th floor NY, NY 10010 The ipicturebooks World Wide Web Site Address is: http://www.ipicturebooks.com For information address: Bantam Books Original ISBN 0-553-27231-4 eISBN 1-5909-079-3 This text converted to eBook format for the Microsoft Reader. Copyright @ 1988, 2001 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications “Time Machine” is a registered trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark office. Cover painting by Steve Fastner Cover design by Alex Jay An ipicturebooks.com ebook ipicturebooks.com 24 West 25th St., 11th fl. NY, NY 10010 The ipicturebooks World Wide Web Site Address is: http://www.ipicturebooks.com Original ISBN: 0-553-27231-4 eISBN: 1-588-24454-7 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 5 ATTENTION TIME TRAVELER! This book is your time machine. -

106Th AIR REFUELING SQUADRON

106th AIR REFUELING SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 106th Aero Squadron organized 27 Aug 1917 Redesignated 800th Aero Squadron, 1 Feb 1918 Demobilized: A and B flights on 8 May 1919, C flight, 2 Jul 1919 135th Squadron organized, 21 Jan 1922 Redesignated 135th Observation Squadron, 25 Jan 1923 Redesignated 114th Observation Squadron, 1 May 1923 Redesignated 106th Observation Squadron, 16 Jan 1924 800th Aero Squadron reconstituted and consolidated with 106th Observation Squadron, 1936 Ordered to active service, 25 Nov 1940 Redesignated 106th Observation Squadron (Medium), 13 Jan 1942 Redesignated 106th Observation Squadron, 4 Jul 1942 Redesignated 106th Reconnaissance Squadron (Bombardment), 2 Apr 1943 Redesignated 100th Bombardment Squadron (Medium), 9 May 1944 Inactivated, 11 Dec 1945 Redesignated 106th Bombardment Squadron (Light), and allotted to ANG, 24 May 1946 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (Night Photo), 1 Feb 1951 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, 9 Jan 1952 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (Photo Jet), 1 May 1957 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron Redesignated 106th Reconnaissance Squadron, 15 Mar 1992 Redesignated 106th Air Refueling Squadron, Oct 1994 STATIONS Kelly Field, TX, 27 Aug 1917 St Maixent, France, 2 Jan 1918 Champ de Tir de Souge, France, 28 Feb 1918-Apr 1919 (headquarters and A Flight) B flight at Camp de Coetquidan, Morbihan, 1 Mar-28 Oct 1918, with detachment thereof at Camp de Meucon, Morbihan, May-Oct 1918; C flight at Le Valdahon, 2 Mar 1918-May -

Franz Stigler, a Hero Because He Did Not Shoot by André Ammer

from Verlag Nürnberger Presse, December 20, 2018 A Hero Because He Did Not Shoot by André Ammer 75 years ago today one of the most notable stories of the Second World War oc- curred over the skies of northern Germany. A German fighter spared a heavily damaged bomber of the U.S. Air Force and escorted it to a safe return flight over the North Sea. Half a century later, the flying ace from Regensburg and the US pi- lot met again. REGENSBURG - Franz Stigler hears the enemy plane long before he sees it. He has been battling U.S. bombers and hunters for several hours and is dead tired when he lands on the Jever airbase, but adrenaline has sharpened his senses. A B-17 flies toward him so slowly and low that it looks like it's about to land. Stigler throws his cigarette away, jumps into his freshly refueled and rearmed Messer- schmitt Bf 109 and takes up the pursuit. Quickly the Regensburger has caught up with the bomber and is surprised that he is not shot at. As he approaches, the reason becomes clear to him. The plane, piloted by 21-year-old Charles Brown, is almost defenseless. Although the Boeing B-17 is nicknamed "Flying Fortress" because it is still capable of flying even with heavy damage, this machine has been incredibly damaged. That she can even hold herself in the air is close to a miracle. Stigler sees that the fuselage and wings of the machine, nicknamed "Ye Olde Pub", are littered with fist-sized holes. -

1945-12-11 GO-116 728 ROB Central Europe Campaign Award

GO 116 SWAR DEPARTMENT No. 116. WASHINGTON 25, D. C.,11 December- 1945 UNITS ENTITLED TO BATTLE CREDITS' CENTRAL EUROPE.-I. Announcement is made of: units awarded battle par- ticipation credit under the provisions of paragraph 21b(2), AR 260-10, 25 October 1944, in the.Central Europe campaign. a. Combat zone.-The.areas occupied by troops assigned to the European Theater of" Operations, United States Army, which lie. beyond a line 10 miles west of the Rhine River between Switzerland and the Waal River until 28 March '1945 (inclusive), and thereafter beyond ..the east bank of the Rhine.. b. Time imitation.--22TMarch:,to11-May 1945. 2. When'entering individual credit on officers' !qualiflcation cards. (WD AGO Forms 66-1 and 66-2),or In-the service record of enlisted personnel. :(WD AGO 9 :Form 24),.: this g!neial Orders may be ited as: authority forsuch. entries for personnel who were present for duty ".asa member of orattached' to a unit listed&at, some time-during the'limiting dates of the Central Europe campaign. CENTRAL EUROPE ....irst Airborne Army, Headquarters aMd 1st Photographic Technical Unit. Headquarters Company. 1st Prisoner of War Interrogation Team. First Airborne Army, Military Po1ie,e 1st Quartermaster Battalion, Headquar- Platoon. ters and Headquarters Detachment. 1st Air Division, 'Headquarters an 1 1st Replacementand Training Squad- Headquarters Squadron. ron. 1st Air Service Squadron. 1st Signal Battalion. 1st Armored Group, Headquarters and1 1st Signal Center Team. Headquarters 3attery. 1st Signal Radar Maintenance Unit. 19t Auxiliary Surgical Group, Genera]1 1st Special Service Company. Surgical Team 10. 1st Tank DestroyerBrigade, Headquar- 1st Combat Bombardment Wing, Head- ters and Headquarters Battery.: quarters and Headquarters Squadron. -

Bjects Celebrating the 175Th Anniversary of the Georgia Historical Society 2 | GEORGIA HISTORY in TWENTY-FIVE OBJECTS

GEORGIA ISTORY H in 25 OBJECTS Celebrating the 175th Anniversary of the Georgia Historical Society 2 | GEORGIA HISTORY IN TWENTY-FIVE OBJECTS nyone traversing modern-day Georgia will find a land that both resembles and stands in stark contrast to the image of the state in popular culture. From The Colony the towering skyscrapers and traffic jams of Atlanta to the moss-draped oaks Savannah is one of the world’s and quiet, historic squares of Savannah, the state seems a paradox in itself, premier tourist destinations, home comfortably straddling both the old and the new. Somehow, in that uniquely southern to the largest urban National way,A the past and the present merge into one. Georgians may not live in the past, to Historic Landmark district in the paraphrase the historian David Goldfield, but the past clearly lives in Georgians. country. Its stately squares and moss-draped oaks offer one of the Understanding how our world was created—how the past and the present merge—is the most scenic and historic landscapes mission of the Georgia Historical Society. Founded in 1839 as the independent, statewide in America. Its origins lie in the institution responsible for collecting and teaching Georgia and American history, the vision of its founder, James Edward Society has amassed an amazing collection of Georgia-related materials over the past Oglethorpe, and in the artifact seen 175 years, including over 4 million documents, letters, photographs, maps, portraits, rare below—the brass surveyor’s compass books, and artifacts, enough to create a museum of Georgia history. used by Oglethorpe to lay out the city. -

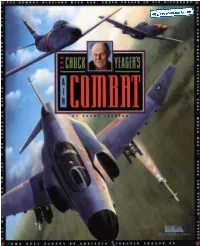

Chuck Yeagers Air Combat - Manual.Pdf

★ AIR COMBAT ★ 1 A DIFFERENT KIND OF COMBAT You’ve spent your life training to be a fighter pilot and dreaming of the day you’d actually get to fly. Hours, weeks, years invested in practice and training. All your hard work and time finally pay off and you develop into a world renown ace. You owe a lot to the flying aces that came before you. The teachers who taught you excellence. You pay them back by teaching other green boys about what it takes to be a flying ace and the edge they need for fighting well. You put back what you took out so more pilots can train and defend the nation. There are, however, some selfish aces out there who don’t give a damn about anyone else. These aces take all they can and say ‘to hell with the pros who came before’. Software publishing is much the same: most consumers pay for their software, but some green boys out there don’t. They copy software and don’t pay their dues to the teams responsible for bringing them the goods in the first place. When that happens, software companies don’t have the money they need to keep turning out the best software they can — some even go under. Electronic Arts is an ace in the field, giving you the best we can. Help us to keep putting out the best by stopping software piracy. As a member of the Software Publishers Association (SPA), Electronic Arts supports the fight against the illegal copying of personal computer software. -

US Army Air Force 100Th-399Th Squadrons 1941-1945

US Army Air Force 100th-399th Squadrons 1941-1945 Note: Only overseas stations are listed. All US stations are summarized as continental US. 100th Bombardment Squadron: Organized on 8/27/17 as 106th Aero Squadron, redesignated 800th Aero Squadron on 2/1/18, demobilized by parts in 1919, reconstituted and consolidated in 1936 with the 135th Squadron and assigned to the National Guard. Redesignated as the 135th Observation Squadron on 1/25/23, 114th Observation Squadron on 5/1/23, 106th Observation Squadron on 1/16/24, federalized on 11/25/40, redesignated 106th Observation Squadron (Medium) on 1/13/42, 106th Observation Squadron on 7/4/42, 106th Reconnaissance Squadron on 4/2/43, 100th Bombardment Squadron on 5/9/44, inactivated 12/11/45. 1941-43 Continental US 11/15/43 Guadalcanal (operated through Russell Islands, Jan 44) 1/25/44 Sterling Island (operated from Hollandia, 6 Aug-14 Sep 44) 8/24/44 Sansapor, New Guinea (operated from Morotai 22 Feb-22 Mar 45) 3/15/45 Palawan 1941 O-47, O-49, A-20, P-39 1942 O-47, O-49, A-20, P-39, O-46, L-3, L-4 1943-5 B-25 100th Fighter Squadron: Constituted on 12/27/41 as the 100th Pursuit Squadron, activated 2/19/42, redesignated 100th Fighter Squadron on 5/15/42, inactivated 10/19/45. 1941-43 Montecorvino, Italy 2/21/44 Capodichino, Italy 6/6/44 Ramitelli Airfield, Italy 5/4/45 Cattolica, Italy 7/18/45 Lucera, Italy 1943 P-39, P-40 1944 P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51 1945 P-51 100th Troop Carrier Squadron: Constituted on 5/25/43 as 100th Troop transport Squadron, activated 8/1/43, inactivated 3/27/46. -

The Way We Were Part 1 By: Donna Ryan

The Way We Were Part 1 By: Donna Ryan The Early Years – 1954- 1974 Early Years Overview - The idea for the Chapter actually got started in June of 1954, when a group of Convair engineers got together over coffee at the old La Mesa airport. The four were Bjorn Andreasson, Frank Hernandez, Ladislao Pazmany, and Ralph Wilcox. - The group applied for a Chapter Charter which was granted two years later, on October 5, 1956. - Frank Hernandez was Chapter President for the first seven years of the Chapter, ably assisted by Ralph Wilcox as the Vice President. Frank later served as VP as well. The first four first flights of Chapter members occurred in 1955 and 1957. They were: Lloyd Paynter – Corbin; Sam Ursham - Air Chair; Frank Hernandez - Rapier 65; and Waldo Waterman - Aerobile. - A folder in our archives described the October 15-16, 1965 Ramona Fly-in which was sponsored by our chapter. Features: -Flying events: Homebuilts, antiques, replicas, balloon burst competition and spot landing competitions. - John Thorp was the featured speaker. - Aerobatic display provided by John Tucker in a Starduster. - Awards given: Static Display; Safety; Best Workmanship; Balloon Burst; Aircraft Efficiency; Spot Landings. According to an article published in 1997, in 1969 we hosted a fly-In in Ramona that drew 16,000 people. Some Additional Dates, Numbers, Activities June 1954: 7 members. First meeting was held at the old La Mesa Airport. 1958: 34 members. First Fly-in was held at Gillespie Field. 1964: 43 members. Had our first Chapter project: ten PL-2’s were begun by ten Chapter 14 members. -

Allied Expeditionary Air Force 6 June 1944

Allied Expeditionary Air Force 6 June 1944 HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY AIR FORCE No. 38 Group 295th Squadron (Albemarle) 296th Squadron (Albemarle) 297th Squadron (Albemarle) 570th Squadron (Albemarle) 190th Squadron (Stirling) 196th Squadron (Stirling) 299th Squadron (Stirling) 620th Squadron (Stirling) 298th Squadron (Halifax) 644th Squadron (Halifax) No 45 Group 48th Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 233rd Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 271st Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 512th Squadron (C-47 Dakota) 575th Squadron (C-47 Dakota) SECOND TACTICAL AIR FORCE No. 34 Photographic Reconnaissance Group 16th Squadron (Spitfire) 140th Squadron (Mosquito) 69th Squadron (Wellington) Air Spotting Pool 808th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 885th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 886th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 897th Fleet Air Arm Squadron (Seafire) 26th Squadron (Spitfire) 63rd Squadron (Spitfire) No. 2 Group No. 137 Wing 88th Squadron (Boston) 342nd Squadron (Boston) 226th Squadron (B-25) No. 138 Wing 107th Squadron (Mosquito) 305th Squadron (Mosquito) 613th Squadron (Mosquito) NO. 139 Wing 98th Squadron (B-25) 180th Squadron (B-25) 320th Squadron (B-25) No. 140 Wing 21st Squadron (Mosquito) 464th (RAAF) Squadron (Mosquito) 487t (RNZAF) Squadron (Mosquito) No. 83 Group No. 39 Reconnaissance Wing 168th Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 414th (RCAF) Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 430th (RCAF) Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 1 400th (RCAF) Squadron (Spitfire) No. 121 Wing 174th Squadron (Typhoon) 175th Squadron (Typhoon) 245th Squadron (Typhoon) No. 122 Wing 19th Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 65th Squadron (P-51 Mustang) 122nd Squadron (P-51 Mustang) No. 124 Wing 181st Squadron (Typhoon) 182nd Squadron (Typhoon) 247th Squadron (Typhoon) No. 125 Wing 132nd Squadron (Spitfire) 453rd (RAAF) Squadron (Spitfire) 602nd Squadron (Spitfire) No. -

Second Saturday @ Museum SPECIAL VETERANS DAY RECOGNITION PROGRAM for America's Flying Ace New Hampshire's Native Son

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FROM: Jack Ferns, Executive Director Aviation Museum of New Hampshire 27 Navigator Road Londonderry, NH 03053 (603) 669-4877 Second Saturday @ Museum SPECIAL VETERANS DAY RECOGNITION PROGRAM FOR America’s Flying Ace New Hampshire’s Native Son, Joe McConnell It’s been nearly sixty years since the tragic loss of Dover native and national US Air Force hero Captain Joseph Christopher McConnell Jr. To this day Captain McConnell remains the top American air ace; a triple-ace having recorded 16 shoot-downs of MIGs n the Korean War with F86 Sabre Jets (“MIG:” from the Russian term Mikoyan-Gurevich Design Bureau which was responsible for developing the Soviet aircraft design). McConnell was also the first jet-on-jet fighter ace and ranks among the top ten aces in world aviation history. He was born in Dover in 1922, the son of Joseph C. McConnell Sr. and Phyllis Winfred Brooks, and attended local schools. He started his military career in 1940 when he enlisted the First Infantry Division of the US Army at Fort Devens, Mass. Later he received a transfer to the Air Corps. His dream of becoming a fighter pilot was dashed when instead of going to pilot training he was assigned to navigator school. Upon being certified a navigator, he flew combat missions in World War II in Europe as the navigator on a B-24 Liberator. On August 20, 1942 he married Pearl Edna “Butch” Brown in Fitchburg, Mass. He eventually entered flight training and in 1948 he achieved his goal of becoming a fighter pilot. -

And Space Travel by David Gustafson Burt

Burt Rutan: Icon of Homebuilding…And Space Travel By David Gustafson Burt Rutan’s list of airplanes designed and flown (45), of honorary Doctoral Degrees (6!), of naonal and internaonal awards (112… not counng the milk drinking contest he won at the age of 12), of patents held (7), and of design projects related to aviaon in some way (several hundred) takes up 11 pages! This all occurred in the years between 1965, when he graduated from California Polytechnic University, and his rerement from Scaled Composites in April, 2011. It includes a work schedule that would have crippled most people: escalang over the forty-six years he spent in the high desert to six or seven days a week, 8 to 16 hours a day. Vacaon me was rare. “I think the main reason is there wasn’t much to do in Mojave. I kept my head down and my elbows up and I worked like hell.” When he rered, he found “with a clear calendar, I could sleep in and then decide on a given day what I would do aer I woke up. That concept was so foreign to me that it was absolutely amazing. I sll haven’t goen used to it.” He’s sll looking for the “off” switch. In his lifeme he went from model airplanes to rocket science, from homebuilts to transports, from internaonally recognized projects like the Voyager and Spaceship One to classified stuff we will probably never know about. He changed the culture of aviaon. Burt evolved into an unusual blend of scienst and arst. -

Up from Kitty Hawk Chronology

airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology AIR FORCE Magazine's Aerospace Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk PART ONE PART TWO 1903-1979 1980-present 1 airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk 1980-1989 F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighters, first flight June 1981. Articles noted throughout the chronology are hyperlinked to the online archive for Air Force Magazine and the Daily Report. 1980 March 12-14, 1980. Two B-52 crews fly nonstop around the world in 43.5 hours, covering 21,256 statute miles, averaging 488 mph, and carrying out sea surveillance/reconnaissance missions. April 24, 1980. In the middle of an attempt to rescue US citizens held hostage in Iran, mechanical difficulties force several Navy RH-53 helicopter crews to turn back. Later, one of the RH-53s collides with an Air Force HC-130 in a sandstorm at the Desert One refueling site. Eight US servicemen are killed. Desert One May 18-June 5, 1980. Following the eruption of Mount Saint Helens in northwest Washington State, the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service, Military Airlift Command, and the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing conduct humanitarian-relief efforts: Helicopter crews lift 61 people to safety, while SR–71 airplanes conduct aerial photographic reconnaissance. May 28, 1980. The Air Force Academy graduates its first female cadets. Ninety-seven women are commissioned as second lieutenants. Lt. Kathleen Conly graduates eighth in her class. Aug. 22, 1980. The Department of Defense reveals existence of stealth technology that “enables the United States to build manned and unmanned aircraft that cannot be successfully intercepted with existing air defense systems.” Sept.